Ah, August. Here at HeinOnline headquarters, located in Great Lake-side Erie County, NY, we’re soaking up summer before the leaves start changing and the snow starts falling (and falling, and falling, and falling…). Discerning residents of Erie County know August is the superior summer month, for every year it brings the ultimate, unbeatable, uncontested best twelve days of summer: the Erie County Fair.

But COVID-19 has postponed this venerable celebration of agriculture and fried food until 2021, and this Hein blogger is feeling wistful about all the county fairs, carnivals, and circuses that have been sidelined until a summer when we are able to cease social distancing. So dump some powdered sugar on your funnel cake, grab an ice cold birch beer, and join us on the midway for a HeinOnline guided tour of these great traveling temporary amusements.

Step right up, step right up! Make sure you have the databases we’ll be mentioning so you can follow along.

- Animal Studies: Law, Welfare and Rights

- Business and Legal Aspects of Sports and Education

- Early American Case Law

- Fastcase

- Intellectual Property Law Collection

- Law Journal Library

- Session Laws Library

- U.S. Congressional Documents

- U.S. Federal Agency Documents, Decisions, and Appeals

- U.S. Supreme Court Library

Rural America Plays

The county fair, or agricultural fair as it is sometimes called, was originally formed as a way to give our rural ancestors a break from the farm and to show off their prized livestock, produce, and other goods. Combining competitions, livestock shows, and games of chance, these fairs were a way for isolated 19th century rural families to come together and socialize.

The Erie County Fair is a prime example of these fairs. First held in 1820 in Buffalo, NY by the Niagara County Horticultural Society, the fair was taken over the following year by the newly created Erie County Agricultural Society, which was formed when Erie County was split into Erie and Niagara Counties. The fair has been held annually every year since 1841 with two exceptions: in 1943, when the fair was cancelled for rationing efforts in World War II, and 2020, when it was cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is the second-largest agricultural fair in New York State and the fourth-oldest in the United States.

Skeptical of this blogger’s love for the Erie County Fair? Check out this tribute in the Congressional Record in honor of the fair’s 150th run in 1989, which just so happens to be the year this blogger was born.

Regulating the Big Top

The popularity of county fairs attracted competition from traveling showmen. These unofficial hucksters set up shop outside the fairground entrance, catching crowds on their way in. When we think of these types of amusements we naturally also think of performing ponies, lions jumping through rings of fire, and elephants balancing on balls. Menageries of exotic animals have traveled America since the early 1800s, with the grandfather of America’s most famous circus Hachaliah Bailey touring the Hudson Valley with his elephant Old Bet. Phineas Taylor Barnum, perhaps the most famous of America’s showmen, had been entertaining Americans since the 1840s with dubious curiosities of less-than-certain origin, such as his Fiji mermaid, but also with performers such as General Tom Thumb, jugglers, and exotic animals. Barnum’s failed attempt to purchase the most sensational traveling exhibit of the 1850s, the very fake but very popular Cardiff Giant, led him to create and exhibit a copy of the Giant; the subsequent arguing over which was the “real” article was eventually settled in the courtroom.

These early troupes moved from town to town by wagon and eventually by train. The circus train, with its carts of exotic animals turning their noses into the wind and miles of colorfully painted boxcars chugging from outpost to outpost is an indelible mental image of Americana. Railroad workers’ unions negotiated special freight rates for circus trains to cover their rail passage and loading and unloading. With the passage of time, semi-trucks have become the dominant mode of transportation for carnivals and circuses, but some still ride the rails; the James E. Strates Shows, whose traveling carnival midway serves fairs throughout the United States, including the Erie County Fair, is the only midway that still transports by train.

The midway, that magical stretch of dazzling lights, whirring rides, delighted screams, and games of chance, is the heart of any traveling fair. The term midway dates back to 1893 and the World’s Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair. Held to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the New World, the Exposition lasted for six months and hosted 27 million visitors. Spread across 700 acres, exhibits were separated from amusements, with amusements housed at Midway Plaisance, a park on Chicago’s South Side. And thus the term “midway” entered America’s vocabulary.

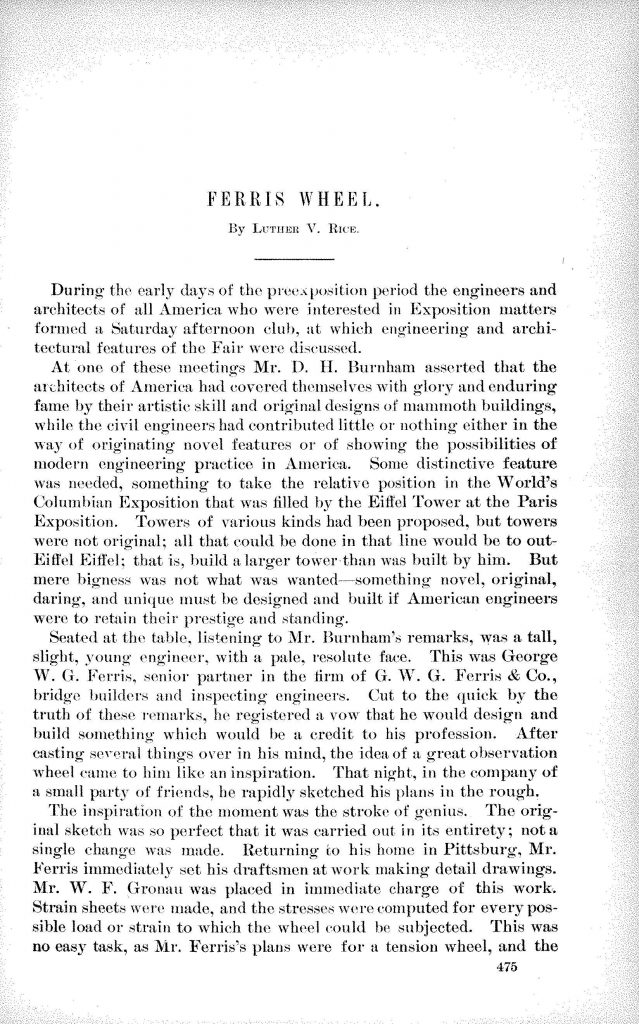

The ferris wheel, that quintessential landmark on any fair’s skyline, made its debut at the World’s Columbian Exposition. Designed by George W.G. Ferris, Jr., the ferris wheel was an instant success, carrying 4,000 people an hour.

Carousels are an ancient ride when compared to the modern ferris wheel, with origins in medieval training tools for jousting knights. As a carnival ride, the 19th century saw both an improvement in technology and a wide variety of styles that varied from elaborately decorated ponies to more realistic and understated horses.

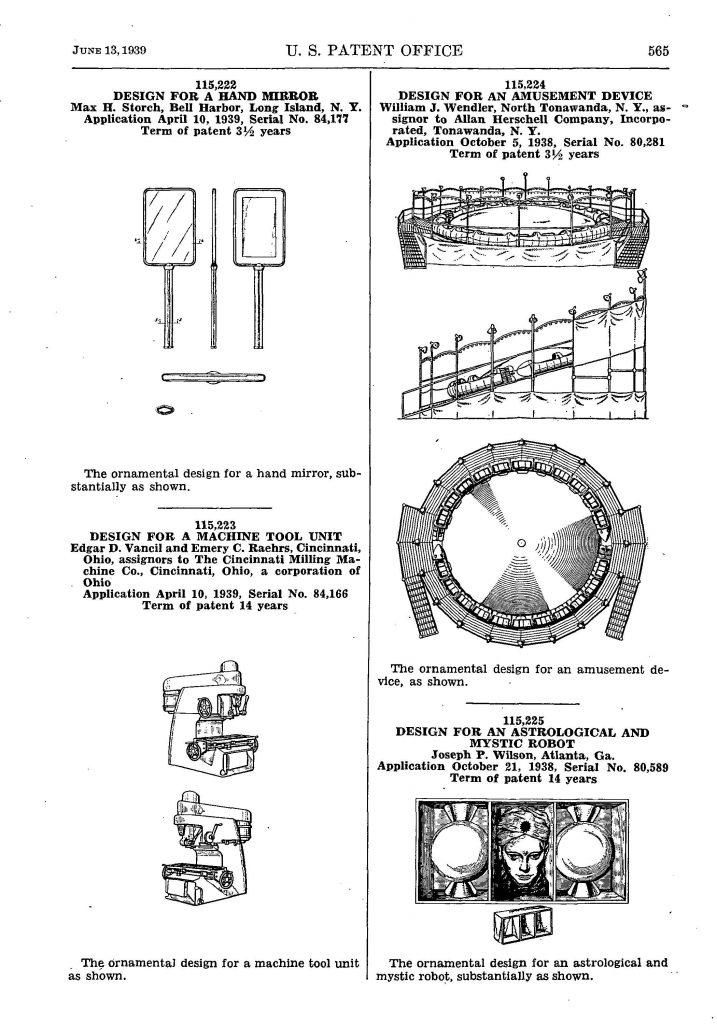

One of these carousel pioneers was Allan Herschell. Herschell’s company, located just a short drive north from Hein headquarters in North Tonawanda, NY, produced a variety of amusement park rides but specialized in wooden carousels, several of which survive today. View this 1939 patent application from the Herschell Company in the Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office.

With so many carnivals, fairs, and circuses coming into town and competing for crowds in America’s early years, some counties enacted laws to give preference to the local county fair. These statutes from South Carolina, for example, state that “no circus, carnival or traveling show of any kind exhibiting under canvas shall be licensed or allowed to exhibit or do business under any auspices or condition within thirty days prior to the opening of the county fair.”

Protecting assets and profits may cause some readers to arch an eyebrow when they recall how effortlessly their pockets turned out money at the promise of seeing “The World’s Only…” or how easily they were charmed by an impossibly large stuffed animal that could be won for conquering a “simple” game. With so much competition for the attention (and dollars) of the masses, circuses and carnivals fiercely guard what makes them unique. Two notable examples of this have even reached the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Big Show Goes to the Supreme Court

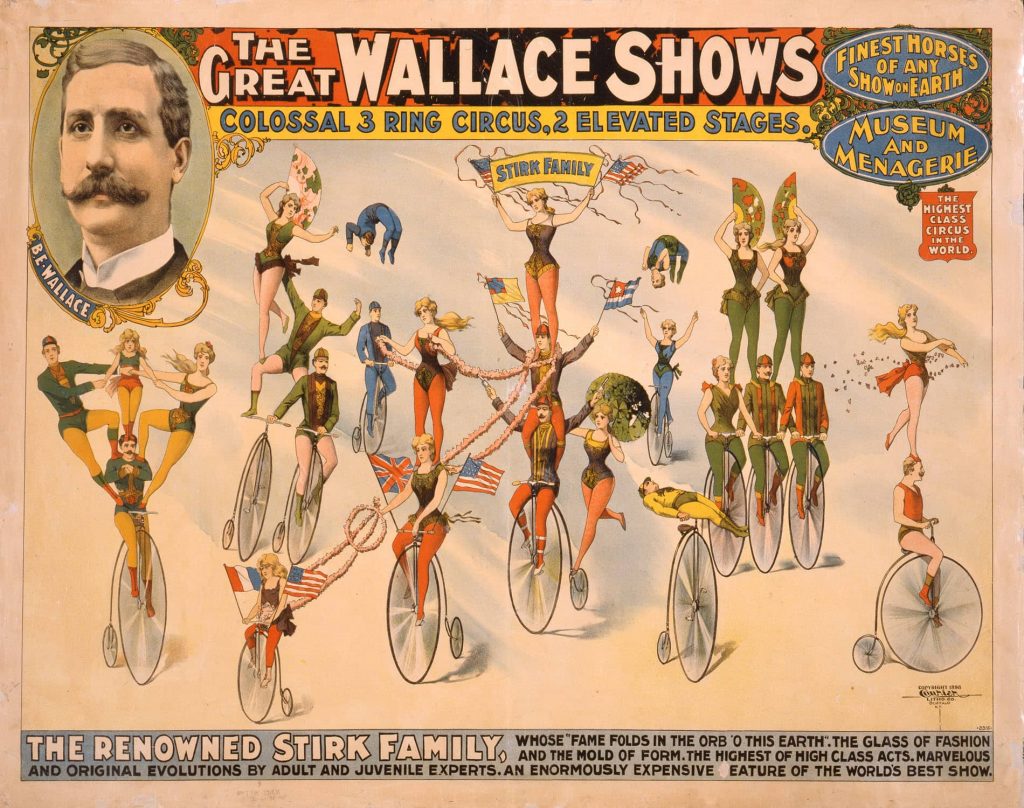

In 1903, before advertising was done on the internet, television, and radio, the Great Wallace Circus relied on posters to promote itself. Showing acrobats, ballet dancers, and living statues, the posters were created by the Courier Lithographing Company after being hired by the Wallace Circus. When the circus ran out of posters, it hired competitor Donaldson Lithographing Company to manufacture copies of the original posters, and Courier subsequently sued Donaldson for copyright infringement. Donaldson objected, arguing that advertisements could not be copyrighted.

The case, Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Company, reached the Supreme Court, with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes writing the opinion that the advertisements, referred to as “tawdry pictures” by the lower court, were protected by copyright. Holmes’s famous opinion states:

It would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations, outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits. At the one extreme some works of genius would be sure to miss appreciation. Their very novelty would make them repulsive until the public had learned the new language in which their author spoke. It may be more than doubted, for instance, whether the etchings of Goya or the paintings of Manet would have been sure of protection when seen for the first time.

The county fair would have its day in the Supreme Court in 1977. In August 1972, Hugo Zacchini was performing his human cannonball act at the Geauga County Fair in Burton, Ohio. Notably, Zacchini was the first to use a compressed air cannonball. Zacchini noticed a reporter from the Scripps-Howard Broadcasting Co. with a camera in the crowd and asked him not film his act. The reporter, however, returned the next day and filmed Zacchini’s entire act and the footage was aired on the nightly news. Zacchini sued, arguing unlawful appropriation, and the case eventually reached the Supreme Court to decide whether Scripps-Howard was immune from damages under the First and Fourteenth Amendment for infringing on an entertainer’s state-law right of publicity.

The Court, with Justice Byron White writing the majority opinion, ruled in favor of Zacchini, stating “the broadcast of a film of petitioner’s entire act poses a substantial threat to the economic value of that performance… if the public can see the act for free on television, it will be less willing to pay to see it at the fair.” It was the first case the Court heard on the right to publicity. Zacchini, however, did not live long enough to see his victory in the nation’s highest court; he died in 1975.

Cruelty or Entertainment?

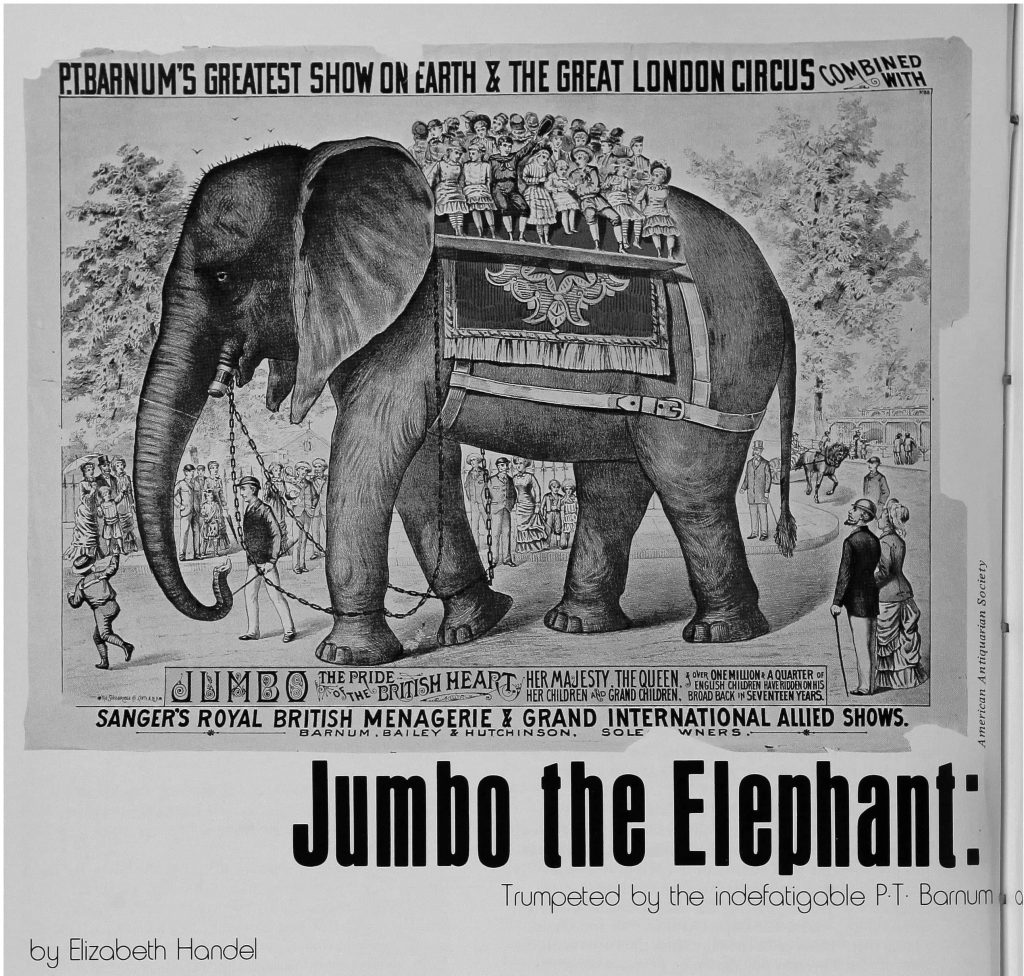

No post on traveling amusements would be complete without a discussion of the conditions performing circus animals can face, and no animal is more symbolic of this reckoning than the elephant. Earlier in this post, Hachaliah Bailey and his traveling elephant Old Bet were mentioned. Old Bet was the first circus elephant in America and a huge attraction for Bailey; she was shot to death by an irate farmer in 1816. Jumbo, P.T. Barnum’s famous circus elephant, spent his life in captivity and only lived for four years in Barnum’s circus before he was struck by a freight train and killed.

Since Jumbo and Old Bet’s time, attitudes over elephants—highly intelligent and social creatures that thrive in close-knit family units—and whether they should be exhibited in circuses and trained to perform have changed. Famously, a protracted case between the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) and Feld Entertainment, which operated the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, ended with the ASPCA paying $9.3 million to settle when a key witness to alleged elephant abuse changed his testimony. Animal welfare organizations cite a lack of enforcement of existing legal protections for these animals, while also pointing to the effects of animals living a life against their biological needs—for example, young and ill elephants being performed to death, baby elephants being separated from their mothers too early in life, and elephants being beaten and wounded by bullhooks.

New Jersey banned all wild or exotic animals from traveling circuses in 2018 with Nosey’s Law, making it the first state to take such action. The law was named for Nosey, a 36-year-old African elephant who performed in a traveling circus despite being afflicted with crippling arthritis. But it was public pressure, not federal action, that led Ringling Brothers to phase out elephants from all its shows in 2016; a drop in ticket sales eventually forced the 146-year-old circus to close the following year.

Interested in researching animal rights further? The Hein Blog has a selection of posts dedicated to animal law, including this one from the archives specifically on circus elephants.

The Show Must Go On

While it may not provide quite the same thrill as the tilt-o-whirl, the HeinOnline blog provides amusement for ladies, gentlemen, boys and girls of all ages. Subscribe to get this content delivered straight to your inbox and never miss a post. You never know what you might learn.