It’s easy to recall some of U.S. history’s most notable events, such as World War I, the fight for civil rights, or the moon landing. If you’re a history buff, you probably are well aware of moments like the Chernobyl disaster, FDR’s New Deal, or the Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution.

American history is brimming with lesser-known—but still fascinating—phenomena that even the most diligent historian may have forgotten. Keep reading to explore a few of these stories with HeinOnline.

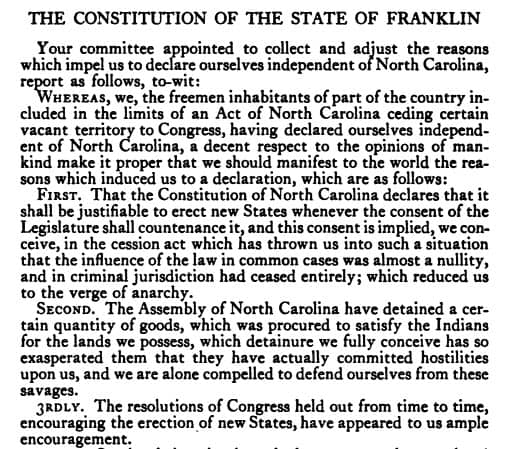

1. Franklin: The Almost 14th State

At the close of the American Revolution, the newly formed U.S. Congress was deep in debt. In 1784, the province of North Carolina voted to cede 29 million acres of land between the Allegheny Mountains and the Mississippi River to Congress to ease its financial troubles. The U.S. government had two years to accept responsibility for the area; however, in the meantime, western settlements on this land feared that they would be left to handle the nearby Cherokee people alone, or even that Congress would sell the territory off to a foreign entity. A few months later, North Carolina rescinded its offer after re-evaluation, reclaiming authority over the land (now eastern Tennessee).

Unhappy with North Carolina’s governance over the area, frontiersmen from the region sought to establish their land as a separate, independent state called “Frankland.” In August of 1784, delegates from the counties in question gathered in Jonesborough, elected leaders for their new state, and drafted a state constitution.

On May 16, 1785, they petitioned Congress for statehood. Seven out of the thirteen existing U.S. provinces voted in favor, but this was less than the two-thirds majority required by the Articles of Confederation. Attempting to bolster their petition, Frankland leaders changed the name of the area to “Franklin” and attempted to garner support from founding father Benjamin Franklin. Though he declined, “Franklinites” existed in their own little republic for just over four years, expanding their territory gradually by seizing it from the indigenous population. After conflict with the North Carolina administration, the Franklin government collapsed in early 1789, and North Carolina resumed full control of the land. Not long after, North Carolina voted again to cede the area to Congress, and it became part of the Southwest Territory (eventually, Tennessee).

Fun fact: Folk hero Davey Crockett was born in the state of Franklin, and his father was a passionate Franklinite.

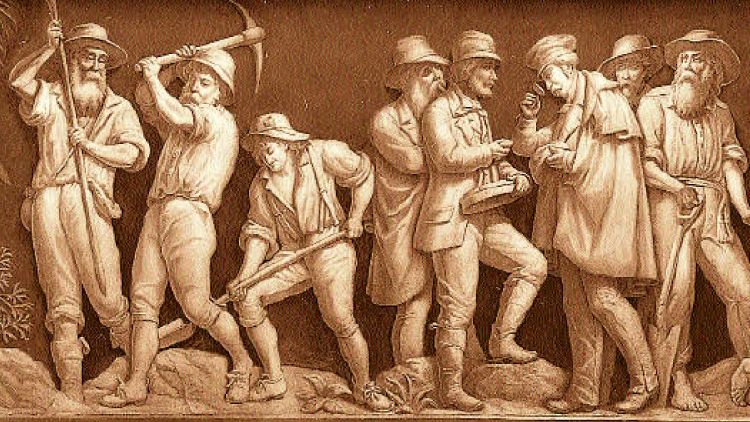

2. The Gold Rush Before the Gold Rush

Most of us know about the discovery of gold in the U.S. territory of California which encouraged travel to the area, assisted economic development, led to California’s eventual statehood, and influenced the later name of San Francisco’s football team. You may not know, however, that this was all made possible by the first gold rush in the United States, which began in North Carolina fifty years earlier.

In 1799, 12-year-old Conrad Reed was playing in a creek on his parents’ farm when he stumbled across a strange looking 17-pound rock. After lugging it home, he showed it to his family who apparently felt it would make a great doorstop—and it did, for several years. Then, in 1802, Conrad’s father must have had an inkling that the rock could be valuable, so he showed it to a local jeweler. Realizing that it was gold, and also that John Reed must have no knowledge of its value, the jeweler offered to buy the lump for $3.50 (about $63 today).

Reed later learned the true value of his son’s find, and gathered some local men to help scour the rest of his land for more. At one point, they found an even larger nugget totaling 28 pounds, causing a stir amongst local landowners and newspapers. In the first few years to follow, farmers in the area began conducting their own searches on their private land, which were successful but short-lived—soon enough, stream-beds and other shallow areas had been stripped clean. By 1824, more than 2,500 ounces of gold had been deposited in the Philadelphia Mint.

In 1825, a man from Montgomery County, North Carolina excavated the first lode mine shaft, progressing gold mining technology and developing the mining profession. Several mines were subsequently established by the 1830s, and in 1835, President Andrew Jackson signed a law that opened three new branches to mint the newly discovered gold. The gradual increase of skilled miners brought about by this first gold rush paved the way for the success of the California rush of 1849.

3. Chinese Exclusion (and Resistance)

Between 1850 and 1870, more than 200,000 immigrants entered the U.S. from China. In response, Congress passed several acts to limit the further entrance of Chinese or other East Asians. First, the Page Act of 1875 barred “undesirable” immigrants, such as Chinese women who engaged in prostitution, making it much more difficult for any Chinese or East Asian woman to enter the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 further banned all Chinese labor immigrants for ten years, regardless of sex.

Then, in 1892, after the ten-year period defined by the Chinese Exclusion Act came to a close, the Geary Act was passed. It renewed the Chinese Exclusion Act for another ten years, and further required that all Chinese residents register for a permit as proof of residence by the next April. Violations of this law would be punishable by deportation or a year of penal labor; after another ten years, the Geary Act would be renewed with no terminal date.

A few months after the act’s passage, Chinese across the United States began to organize in resistance. From coast to coast, Chinese groups (like the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association) urged Chinese people to avoid registering, and instead fundraise for legal representation—the law was unconstitutional, they claimed. By April 1893 (the act’s deadline), only about 3,000 Chinese had registered, out of an estimated 110,000 living in the United States. Many that refused to register did take legal action, and the issue appeared before the Supreme Court in Fong Yue Ting v. United States that year: the Court ruled in a 5-3 decision to uphold the law. In 1896, a second case brought before the Court (Wong Wing v. United States) invalidated the imprisonment and forced labor penalties outlined in the Geary Act because they conflicted with the right to court and due process under the Fifth and Sixth Amendments.

Ultimately, implementation of the act became nearly impossible, as only about 14% of Chinese people throughout the country ever registered. Thus, the U.S. government was left with the unforeseen task (and cost) of arresting and deporting upwards of 85,000 unregistered individuals. Though essentially moot, the Geary Act nonetheless remained in effect throughout the early 1900s until 1943, when Congress repealed all exclusion acts.

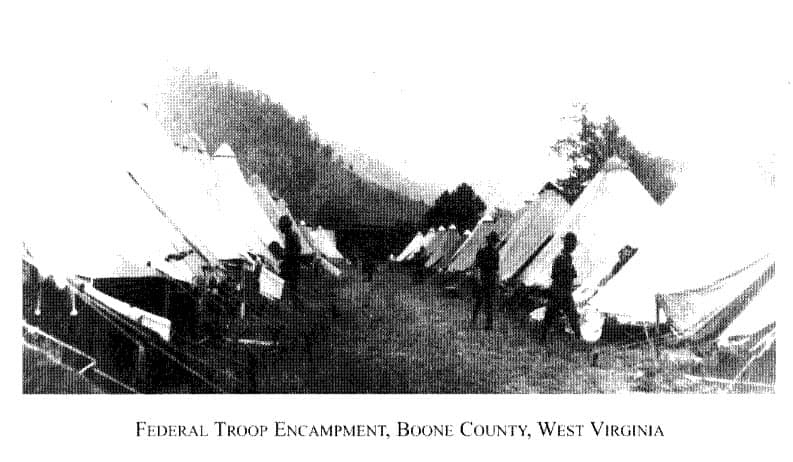

4. The West Virginia Coal Wars

In the late 1800s, a war you probably didn’t hear about prevailed over West Virginia—this one was between coal miners and the coal companies who employed them. For decades, working in the West Virginia coalfields meant low wages, shoddy tools, and extremely unsafe conditions. Unionizing was out of the question, due to strict contracts that called for immediate termination—and eviction, for those who lived in company towns—of any employees found to be union members.

In 1920, the United Mine Workers union succumbed to local pressure to organize in the area, starting with Mingo County. Thousands of county miners joined, and inevitably, the miners were fired. Those who lived in company-owned homes were greeted by private detectives hired by the coal company to enforce eviction.

At one point that May, a dozen of these detectives entered the town of Matewan for this purpose. They first attempted to bribe the mayor to place machine guns on the roofs of town buildings, which the mayor obviously refused. The detectives then set about their duty, but instead of peacefully evicting the families, forced them out of their homes at gunpoint. Hearing reports of this behavior, the town Police Chief, Sid Hatfield, confronted the group and declared that they were under arrest. A gunfight ultimately ensued, and ten men were killed, including the mayor.

This “Matewan Massacre” bolstered the pro-union cause throughout the county. Over the next several months, those for and against unionization engaged in what was essentially guerilla warfare, culminating at times in shootouts, ambushes, and assassinations. The war reached its peak on August 1, 1921, when Sid Hatfield (of Matewan Massacre fame) was killed while walking into a courthouse. Local miners were outraged, and thousands of pro-union activists resolved to march on the coal companies of Mingo County.

Receiving word that the miners would pass through his town, an anti-union sheriff gathered an army of 3,000 state police; together, they set up trenches around the nearby Blair Mountain. On August 28, 10,000 union men approached the ambush, and the largest armed insurrection in the United States since the Civil War ensued. It was not until September 4, when federal troops arrived on the orders of President Warren G. Harding, that the battle finally came to an end. More than 20 union men were charged with treason and hundreds were indicted for murder, though nearly all were acquitted in the end. Workers’ rights to organize would not be legally recognized until the next decade with Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation.

5. That Time the Government Intentionally Poisoned Alcohol

By the early 1900s, the idea of a nationwide prohibition of alcohol had become a significant matter of debate in Congress. When the United States entered World War I, proponents of prohibition in Congress—outnumbering the opposition 140 to 64—saw a new justification for a national alcohol ban: limiting the production of alcohol would allocate more resources, like grain, to the war. In June of 1917, nationwide prohibition of alcohol was proposed as a constitutional amendment and ultimately passed in both houses by December.

Though it supposedly had wartime intentions, the amendment was not ratified until after the war had concluded, in January 1919. Regardless, the prohibition of alcohol was added to the U.S. Constitution as the 18th Amendment, banning the production and sale (but not consumption) of “intoxicating liquors.” To outline the penalties for violating the new amendment, Congress passed the National Prohibition Act, over President Woodrow Wilson’s veto. The act effectively banned all liquor, wine, and beer in the country, and the United States went “dry” on January 17, 1920.

Americans found increasingly creative ways to undermine the 18th Amendment and the National Prohibition Act. One method employed by alcohol “bootleggers” was to steal industrial alcohols (which had not been banned) and resell them as beverages.

This practice became so prevalent (an estimated 60 million gallons were stolen annually by the mid-1920s) that the Treasury Department ordered manufacturers to poison industrial alcohols with additives, creating “denatured alcohol” to discourage consumption. When bootlegging chemists found ways to renature the alcohol, even deadlier poisons like methanol were added, and regulations on denatured alcohol increased.

The intentional poisoning by the U.S. government of industrial alcohols led to the paralysis and death of thousands of drinkers who had bootlegged their beverages. One particular concoction made from industrial alcohol—Ginger Jake—was reportedly responsible for crippling up to 100,000 American drinkers. All in all, it is estimated that approximately 10,000 people were killed by drinking denatured alcohol during this time period.

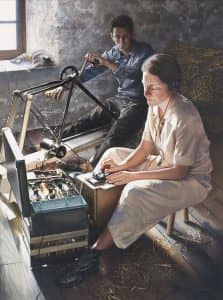

6. The First Female U.S. President

You read that correctly. While the United States may not have seen an official “first female President,” a woman functionally ran the executive branch for more than a year over a century ago.

In August of 1914, President Woodrow Wilson lost his wife, Ellen. The following March, he was introduced to widow Edith Galt through a first cousin. As if in love at first sight, Wilson immediately began showering her with gifts and love notes, some of which probed for her opinion on presidential matters. Three months after their introduction, Wilson proposed (to his advisors’ alarm) and the two were married in December of 1915.

Wilson won another term, and his new wife became his constant companion. She attended his meetings, was given access to classified materials, and even filtered his mail. Toward the end of World War I, she accompanied the President to Europe to attend the 1919 Paris Peace Conference.

Shortly after their return, a stroke left President Wilson paralyzed and bedridden. Instead of encouraging her husband to resign and be replaced by the Vice President, Edith took on a number of his duties herself, hiding the extent of his incapacity from the public. From the time of his stroke to the end of his term in 1921, Edith Wilson was the only connection between the President and other officials, filtering all presidential matters and determining what was important enough to be brought to his bedside.

She was so serious about her new position as “presidential steward” that when the Secretary of State conducted Cabinet meetings without her being present, she had him removed from office. When an ambassador arrived to help negotiate for the President’s version of the League of Nations, she refused him the opportunity unless he fired an aide who had made a joke about her (the ambassador refused).

Edith Wilson analyzed every message delivered to the President, barred all officials from bringing him business, assisted him in completing any necessary tasks, and naturally influenced domestic and international policy in doing so. Though she did not make any crucial decisions, she was accused of running the country in Wilson’s absence—an accusation that she insisted was incorrect up until her death in 1961.

7. The Mid-Century Onion Debacle

In finance, a “future” is a financial contract that allows buyers to purchase a commodity at some point in the future for a price that is set today. The buyer in this instance obviously hopes that the price will go up (meaning they purchased at a lower price) while the seller hopes the price will go down. “Shorting,” as some of us may have learned a few months ago with the GameStop market controversy, is when a futures seller sells borrowed futures, hoping that when it comes time to pay the owner, the price of the future will have gone down (and they can pocket the difference).

In 1955, onion futures became the most traded commodity on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, making up 20% of its trades. Two men, Sam Siegel and Vincent Kosuga, realized this and saw an opportunity. In the fall of that year, they bought literal tons of onions and onion futures until they controlled 98% of all onions in Chicago. By the end of the year, their combined amount of onions totaled 30 million pounds.

After cornering the market, Siegel and Kosuga started to “short sell” onion futures. Typically this would mean that they were betting that the price of onions would decline. Here, though, they weren’t betting. They knew that if they started selling their ridiculous amount of onions, supply would dramatically increase and the price of the vegetable would plummet—so they did. What’s more, when their previously purchased onions started to spoil, they sent them out to be cleaned and repackaged. When they were shipped back, the large incoming shipments of what appeared to be “new” onions signaled incorrectly to futures traders that onions were in abundance—this only drove the price of onions even further down.

While the two men made millions of dollars, the excessive amount of onions being shipped to Chicago caused shortages in the rest of the United States. Meanwhile, onions in Chicago were selling for 10 cents a bag (down from $2.75), bankrupting many farmers whose product was now worthless. Soon, the Commodity Exchange Authority got wind of Siegel and Kosuga’s game and initiated an investigation, while congressional hearings were held on the issue. In the end, the Commodity Exchange Act was amended to prohibit onion futures trading. The law is still in effect today, making onions the only banned trading commodity in the United States.

8. The Woman Who Helped Win World War II

After World War I, damaged nations recuperating after significant losses cultivated expansionist agendas all over the world, setting the stage for a second World War. Germany’s loss of no less than 13% of its home territory, in particular, laid the groundwork for Adolf Hitler’s eventual political takeover in the 1930s.

In the midst of this international tension, one self-described “capricious and cantankerous” woman, Virginia Hall, was determined to become a player. During college, she became fluent in French, German, Italian, and Russian, and after graduation, she applied to the U.S. Foreign Service; being a woman, however, she unfortunately didn’t make the cut. Not to be discouraged, she instead traveled to Europe and began working as a clerk with various U.S. diplomatic institutions. During this period, she accidentally shot herself in the left leg while on a hunting trip, requiring amputation and a wooden replacement (which she lovingly named Cuthbert). Shortly after recovery, Hall applied to the U.S. Foreign Service again, but was rejected once more—this time because of her new disability.

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded its neighbor Poland from the north, south, and west, kickstarting World War II. Initially, Hall contributed to the war effort by driving ambulances for the French army, and in her off-time, speaking passionately about Hitler’s evils to her friends. A British spy, Vera Atkins (sometimes credited as the inspiration for James Bond’s Miss Moneypenny) overheard one of Virginia’s tirades, and recruited her for a secret organization that was being organized by Winston Churchill—the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

As part of the SOE, Hall soon demonstrated proficiency at living in disguise under a fake identity, recruiting loyal resistance spies, uncovering information about German movements, organizing drop zones, and facilitating jailbreaks. According to one report alone, she and her team killed 150 Nazis, captured several hundred more, derailed German freight trains, and detonated several bridges. At one point, her sabotage work became such an inconvenience for the Nazis that she was called “the most dangerous of all Allied spies” by the Gestapo. Only known to them as “the Limping Lady,” she quickly climbed to the top of Germany’s most wanted list.

They never did catch her, however. Upon returning home after the war, Hall was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest military decoration in the United States Army. Her work was still not done—she continued to work for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and then later, for its successor, the Central Intelligence Agency—only leaving when she was required to retire at the age of 60. Today, visitors to the Agency will find a field agent training facility named for the “Limping Lady” and a special section dedicated to her life and work in the Agency museum—notably, she is one of just five agents and the only woman to receive such an honor.

Love History? So Do We!

Did you find these stories fascinating? You’re not alone. We love to write about historical events big and small here at the HeinOnline Blog. Join the community by subscribing today.