November is National Native American Heritage Month, and with Thanksgiving quickly approaching, we are reminded of the rich history and culture of the indigenous peoples of North America, as well as of the often brutal and destructive treatment they have received from the white people who have overtaken their land. It is no surprise that the pathway to indigenous peoples gaining citizenship and the right to vote in America—a land that they inhabited centuries before white Europeans “discovered” it—was tumultuous and hard-won. Using HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set, we take a look at this journey towards basic civil rights for indigenous peoples of the United States.

Citizen vs. Sovereign

Indigenous tribes had governed themselves for centuries before America was founded. Despite the fact that these tribes acted as their own sovereign nations, that didn’t stop white settlers from impeding on their land and making decisions for them. Indigenous peoples were not declared citizens with the passage of the U.S. Constitution in 1788. And in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia,[1]30 (5 Peters) U.S. 1 (1831) Cherokee Nation vs. the State of Georgia, The. This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. the U.S. Supreme Court determined that the tribe was a “dependent nation” and therefore its members did not hold the right to vote.

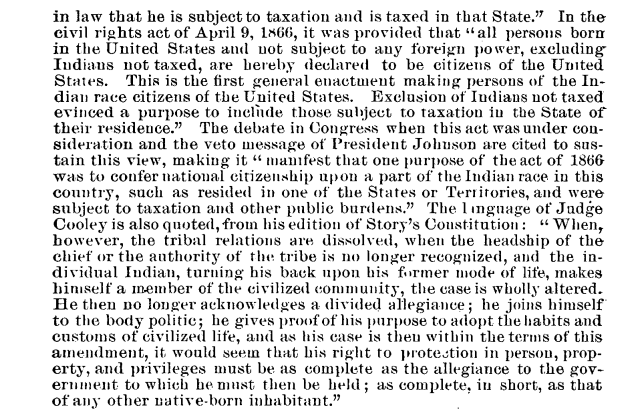

In 1856, Attorney General Caleb Cushing stated, “Indians are the subjects of the United States, and therefore are not, in mere right of home-birth, citizens of the United States.”[2]“History of progress of Indian education and civilization.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1884, pp. 1-694. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset25471&i=146. This document can be found in … Continue reading This attitude was reflected in the passage of the 14th Amendment, which granted Black men the right to vote but did not include indigenous peoples. They weren’t even granted basic civil rights, as the Civil Rights Act of 1866[3]To protect all persons in the United States in their civil rights, and furnish the means of their vindication., Chapter 31, 39 Congress, Public Law 39-31. 14 Stat. 27 (1866). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large … Continue reading explicitly excluded the majority of indigenous peoples when it stated, “That all persons born in the United States, and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States.”[4]“Annual report of Board of Indian Commissioners, 1884.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1884, pp. 681-814. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset25489&i=715. This document can be found in … Continue reading

This was tested when John Elk, an indigenous man in Omaha, NE, attempted to register for elections. He was denied a ballot, and in Elk v. Wilkins,[5]Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94, 122 (1884). This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. it was ruled that indigenous Americans were not protected under the 14th Amendment. Michigan Senator Jacob Howard stated, “I am not yet prepared to pass a sweeping act of naturalization by which all the Indian savages, wild or tame, belonging to a tribal relation, are to become my fellow-citizens and go to the polls and vote with me.”[6]H. Rept. 116-317 197 (2019-11-29) VOTING RIGHTS ADVANCEMENT ACT OF 2019. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

Dawes and Curtis

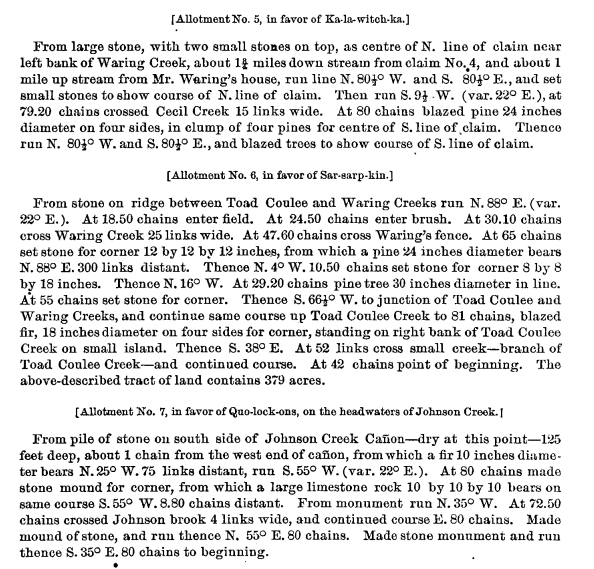

The Dawes Act,[7]Chapter 119, 49 Congress. 24 Stat. 388 (1883-1887) (1887). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. passed in 1887, allowed the president to divide tribal lands, owned communally, into allotments to be owned by indigenous heads of families and individuals[8]“Annual report of Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1887.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1887, pp. 1-910. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset33883&i=386. This document can be found in … Continue reading—essentially forcing indigenous peoples to accept the notion of private property, which previously did not exist among tribes. Tribes could then sell the lands remaining after allotment to the federal government, with the money to be used for creating Indian schools where indigenous children would learn reading, writing, and American culture. Members of certain tribes who accepted the land allotment could then be considered citizens, although not all natives were eligible. The idea was to get indigenous tribes to assimilate into American culture before allowing them to become citizens—however, this did not guarantee the right to vote. Indigenous tribes proceeded to lose millions of acres of land due to this legislation.

However, the Dawes Act didn’t apply to all tribes; the tribes of the Indian Territory were exempt due to previous treaties. However, this changed with the Curtis Act,[9]To provide for the final disposition of the affairs of the Five Civilized Tribes in the Indian Territory, and for other purposes., Public Law 59-129 / Chapter 1876, 59 Congress. 34 Stat. 137 (1906). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. … Continue reading which in 1906 voided tribal governments, laws, and courts in the Five Civilized Tribes, as well as established a committee of five senators[10]“Appropriations for Indian Department, 1908.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1906, p. 1-92. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset29648&i=403. This document can be found in … Continue reading to oversee Indian Territory in relation to this legislation. These laws provided a pathway for indigenous peoples to become citizens, but with significant provisions that required a denial of their culture. Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane noted in 1919, “In my judgment the controlling factor in granting citizenship to Indians should not be based upon their ownership of lands, tribal or in severalty, in trust or in fee, but upon the fact that they are real Americans, and are of right entitled to citizenship.”[11]“Granting citizenship to certain Indians.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1919, p. 1-4. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset24743&i=468. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s … Continue reading

Indian Citizenship Act

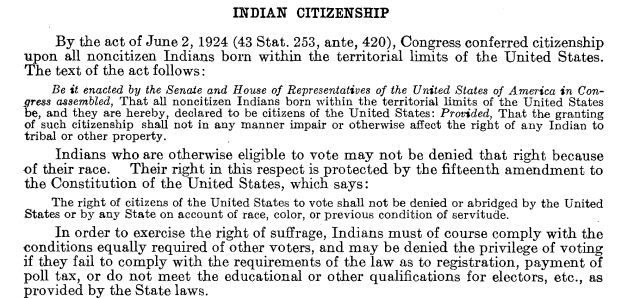

On June 2, 1924, partly to recognize the thousands of indigenous peoples who had served in World War I, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act[12]To reduce and equalize taxation, to provide revenue, and for other purposes., Public Law 68-176 / Chapter 234, 68 Congress. 43 Stat. 253 (1924). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. into law, which granted the right to full citizenship to “all noncitizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States.”[13]“Laws and treaties relating to Indian affairs, v. 4.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1929, p. I-1406. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset24381&i=1171. This document can be found in … Continue reading This law provided citizenship without forcing indigenous peoples to give up their culture or tribal membership, as the law also states that “the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.”[14]“Laws and treaties relating to Indian affairs, v. 4.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1929, pp. I-1406. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset24381&i=1171. This document can be found in … Continue reading However, this act did not guarantee voting rights at the federal level—with the exceptions of the 14th and 19th Amendments, the Constitution provides the states with the responsibility to determine voting eligibility. And several states chose to disenfranchise indigenous peoples.[15]“Laws and treaties relating to Indian affairs, v. 4.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1929, pp. I-1406. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset24381&i=1171. This document can be found in … Continue reading

Over the years, states began to repeal these laws. In 1957, Utah was the last state to officially repeal its law denying the vote to indigenous peoples living on reservations. However, tribe members were still prevented from voting in the same ways that Black people were in the Jim Crow South—through poll taxes, literacy tests, and threats and intimidation.

Temporary Victory for the Vote

Finally, in 1965, the passage of the Voting Rights Act[16]To enforce the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and for other purposes., Public Law 89-110, 89 Congress. 79 Stat. 437 (1965). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. helped to solidify the voting rights that indigenous peoples had won in every state. Section 5 of this law[17]“Voting rights act of 1965.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1965, pp. 1-90. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset22129&i=1258. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. … Continue reading requires any state that has had a history of discrimination in voting policies receive federal approval before making any changes to voting laws, in order to help prevent further racial discrimination at the polls.

However, this was reversed in 2013 with the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder,[18]Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder, Attorney General, et al, 570 U.S. Rep 529, 594 (2013). This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. which stripped the Justice Department of the authority to strike down discriminatory voter laws. In 2019, a federal commission discovered that at least 23 states have passed restrictive voting laws since then.[19]I (2020) Continuing Challenges to the Voting Rights Act since Shelby County v. Holder: Hearing before the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundred … Continue reading

Even today, although indigenous peoples born in America are considered citizens, they face several significant barriers in casting votes. For example, many lack an official residential address, making it difficult to obtain a state ID as well as to receive and send mail-in ballots. Many also lack internet to submit a voter registration. Some native peoples don’t speak or write English[20]“Voting rights act extension, 2 pts.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1981, pp. 1-2. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20721&i=629. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. … Continue reading and require a translator to understand the ballot, and this resource is often not available to them. Additionally, polling places are often far away from reservations, requiring indigenous individuals to take off work and find reliable transportation in order to cast their ballots. Indigenous peoples may have fully gained the right to vote in 1965, but significant challenges still remain nearly six decades later.

Help Us Complete the Project

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Documents from additional HeinOnline databases have been incorporated to supplement research materials for non-U.S. related events discussed.

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us, please contact Steve Roses at 716-882-2600 or sroses@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give special thanks to all of the libraries that have provided generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | 30 (5 Peters) U.S. 1 (1831) Cherokee Nation vs. the State of Georgia, The. This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “History of progress of Indian education and civilization.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1884, pp. 1-694. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset25471&i=146. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑3 | To protect all persons in the United States in their civil rights, and furnish the means of their vindication., Chapter 31, 39 Congress, Public Law 39-31. 14 Stat. 27 (1866). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑4 | “Annual report of Board of Indian Commissioners, 1884.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1884, pp. 681-814. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset25489&i=715. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑5 | Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94, 122 (1884). This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑6 | H. Rept. 116-317 197 (2019-11-29) VOTING RIGHTS ADVANCEMENT ACT OF 2019. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑7 | Chapter 119, 49 Congress. 24 Stat. 388 (1883-1887) (1887). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑8 | “Annual report of Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1887.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1887, pp. 1-910. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset33883&i=386. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑9 | To provide for the final disposition of the affairs of the Five Civilized Tribes in the Indian Territory, and for other purposes., Public Law 59-129 / Chapter 1876, 59 Congress. 34 Stat. 137 (1906). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑10 | “Appropriations for Indian Department, 1908.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1906, p. 1-92. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset29648&i=403. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑11 | “Granting citizenship to certain Indians.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1919, p. 1-4. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset24743&i=468. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑12 | To reduce and equalize taxation, to provide revenue, and for other purposes., Public Law 68-176 / Chapter 234, 68 Congress. 43 Stat. 253 (1924). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑13 | “Laws and treaties relating to Indian affairs, v. 4.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1929, p. I-1406. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset24381&i=1171. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑14, ↑15 | “Laws and treaties relating to Indian affairs, v. 4.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1929, pp. I-1406. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset24381&i=1171. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑16 | To enforce the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and for other purposes., Public Law 89-110, 89 Congress. 79 Stat. 437 (1965). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑17 | “Voting rights act of 1965.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1965, pp. 1-90. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset22129&i=1258. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑18 | Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder, Attorney General, et al, 570 U.S. Rep 529, 594 (2013). This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑19 | I (2020) Continuing Challenges to the Voting Rights Act since Shelby County v. Holder: Hearing before the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixteenth Congress, First Session, June 25, 2019. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑20 | “Voting rights act extension, 2 pts.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1981, pp. 1-2. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20721&i=629. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |