This month, HeinOnline continues its Secrets of the Serial Set series with a consideration of Susan B. Anthony, her trial, and women’s suffrage in general.

Secrets of the Serial Set is a new monthly blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Join us each month to explore notable events in U.S. history with the primary sources themselves. Prepare to be blown away by what the Serial Set has to offer.

About the Serial Set

The United States Congressional Serial Set is considered an essential publication for studying American history. Spanning more than two centuries with more than 17,000 bound volumes, the records in this series include House and Senate Documents, House and Senate Reports, and much more. Documents cover a wide variety of topics, including reports of executive departments and independent organizations, reports of special investigations made for Congress, and annual reports of non-governmental organizations. The Serial Set began publication in 1817 with the 15th Congress, 1st session. U.S. Congressional Documents prior to 1817 are published as the American State Papers.

The Serial Set in HeinOnline

The Serial Set is an ongoing project in HeinOnline with the goal of adding approximately four million pages each year until the archive is completed. As of this month, more than 2.6 million pages and more than 3,300 volumes have been added since HeinOnline launched the Serial Set in October 2018. HeinOnline currently includes:

- Complete indexing of the more than 17,000 volumes of the Serial Set

- Full 40-year (1978-2018) content archive in HeinOnline’s image-based PDF format

- Complete coverage of the American State Papers

- 87% of the Serial Set available in HeinOnline or via links to HathiTrust Digital Library

The Serial Set is included at no additional charge for subscribers of HeinOnline Academic, HeinOnline Core+, and HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. Learn more about the Serial Set and how to contribute to the project by following the link below:

Susan B. Anthony and Women’s Suffrage

Early Life and Activism

Born to a family of Quaker activists, Susan B. Anthony was raised among abolitionists, anti-slavery advocates, and proponents of women’s rights. After moving to Rochester, New York in 1845, the Anthony family became even more immersed in social reform, becoming a part of the local Quaker reform organization known as the Congregational Friends. The Anthony home soon grew to become a gathering place for local activists, including former slave and well-known abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

Known today as a champion of women’s rights, Anthony showed little interest at first in the fight for women’s suffrage. Though the first women’s rights convention took place nearby in Seneca Falls, Anthony did not attend. Likewise, she did not attend the Rochester Women’s Rights Convention of 1848, held in her own hometown. After accepting a headmistress position for the female department of the Canajoharie Academy, Anthony became even more distanced from Quaker influences. She did voice her frustration at being paid much less than men, but had no interest in voting. It was not until she returned to her family’s farm in 1849 that Anthony found herself drawn toward equal rights reform.

Entry into the Women’s Suffrage Movement

In 1851, Susan B. Anthony was introduced by a mutual friend to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, an already prominent women’s rights activist and an organizer of the first convention at Seneca Falls years earlier. As Anthony and Stanton grew closer, they utilized each other’s strengths to develop a partnership which became crucial to the eventual success of the women’s movement. Anthony, who despised writing, delivered speeches and distributed petitions created from the ideas and rhetoric of Stanton.

Anthony entered the women’s rights movement as it began to gather momentum. However, the movement soon faded away with the explosion of the abolitionist movement and beginning of the Civil War. After the war, Anthony and Stanton attempted to revive the women’s rights movement by holding the Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention in 1866. It was at this convention that Anthony proposed combining the two issues of African American and women’s suffrage. Following Anthony’s proposal, the convention voted to change its direction and name, re-establishing itself as the American Equal Rights Association (AERA). The transformation was met with resistance from many, including abolitionists themselves who requested that Anthony back down until black male suffrage had been achieved.

In a controversial move, Susan B. Anthony subsequently campaigned against the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which would allow African Americans to vote. She stood firmly by her position, arguing that if the amendment awarded all men—including those of other races—the right to vote, it would give constitutional authority to the misconception that men are superior to women. The move caused a bitter split in the women’s movement with Anthony and Stanton forming the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and notable activists Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe forming the competing American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The opposing organizations would not merge again until 1890.

While heading the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), Susan B. Anthony committed herself entirely to the women’s suffrage movement and the new organization. By the late 1860s, the movement gradually began to yield results, with women’s suffrage granted in Wyoming in 1869 and in Utah in 1870. In 1871, a convention of the NWSA developed a new strategy, encouraging women to attempt to vote. After being denied, the women would then file federal lawsuits on the basis of the recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment which stated that “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

Anthony’s Arrest and Trial

Emboldened by the new strategy of the NWSA, Susan B. Anthony and fourteen other women cast ballots in the 1872 election between President Ulysses S. Grant and Horace Greeley. On November 18th, Anthony was arrested and charged with illegally voting in the presidential election. Though the fourteen other women were also arrested, they were released on bail pending the results of Anthony’s trial. Anthony, however, refused to post bail. The resulting trial, fraught with controversy, garnered national attention and is viewed as a turning point for the women’s rights movement.

The trial, United States v. Susan B. Anthony, began on June 17th, 1873. Numerous complications surrounded the trial, including that (1) Anthony was tried in federal courts, though accused of violating a state law, (2) presiding Justice Ward Hunt had never previously served as a trial judge, (3) Hunt presided alone, while standard practice necessitated two judges.

Though Anthony asked for permission to testify on her own behalf, Justice Hunt denied her request, referring to a previously established rule of common law which prohibited criminal defendants from testifying in federal courts. Anthony was thus forbidden to speak until after the final verdict had been delivered.

One of the largest controversies surrounding the trial occurred when Justice Hunt delivered his written opinion that Anthony was guilty and directed the jury to deliver a guilty verdict, denying her a trial by jury. On the third day of the trial, when Justice Hunt allowed Anthony to speak, she responded with a speech now renowned in the history of women’s suffrage. Though quickly ordered by Hunt to be silent and seated, Anthony protested the violation of her rights as a U.S. citizen and chastised the judge for denying her a trial by jury. She further stated that had he allowed her a trial by jury, he still would have violated her right to a trial by a jury of her peers due to the fact that women were forbidden from being jurors.

Justice Hunt sentenced Susan B. Anthony to a fine of $100 as punishment for her charges. Anthony responded that she would not pay a dollar of the fine. Had she been taken into custody until the fine had been paid, Anthony would have been able to file a writ of habeas corpus and take her case to the Supreme Court. Instead, Justice Hunt effectively blocked any potential for legal recourse by announcing that Anthony would be released. Subsequent attempts to collect Anthony’s fine failed, and the fine was left unpaid.

Anthony and Suffrage in the Serial Set

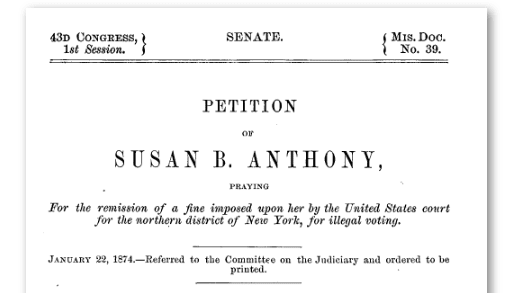

In January of 1874, Susan B. Anthony petitioned Congress for a remission of the fine, claiming that the ruling from Justice Hunt had been unjust given that he denied her a trial by jury.

View the petition in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set and read Anthony’s own words describing the events of her trial. Navigate to the home page of the database and perform a basic full-text search for “Susan B. Anthony” AND “petition” AND “1874” to find the petition itself as the first result.

Other results from the same search further illustrate the aftermath of the Susan B. Anthony trial and petition. Upon receiving Anthony’s petition, Justice Hunt’s ruling was debated by the House and Senate Judiciary Committees. View the House report on the petition here. Later, Congressman Benjamin Butler introduced a bill to remit Anthony’s fine, though it ultimately did not pass.

Susan B. Anthony’s fight for woman suffrage did not end with her trial. In 1879, Anthony (along with Stanton and others) asked the Judiciary Committees to provide for an amendment to the Constitution protecting the rights of women citizens. View the memorial here.

A year later, Anthony and others presented their arguments for women’s suffrage before the Judiciary Committee. Users can find these arguments, including those of Susan B. Anthony, in the Serial Set, too.

In 1900, Anthony was succeeded as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association by Carrie Chapman Catt. Catt revived the work of the NAWSA, redirecting the organization’s focus toward a federal amendment protecting women’s suffrage. In 1914, a constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage—nicknamed the “Susan B. Anthony Amendment”—was finally proposed and considered by the Senate. After numerous rejections, the “Anthony Amendment” was passed as the Nineteenth Amendment on May 21, 1919.

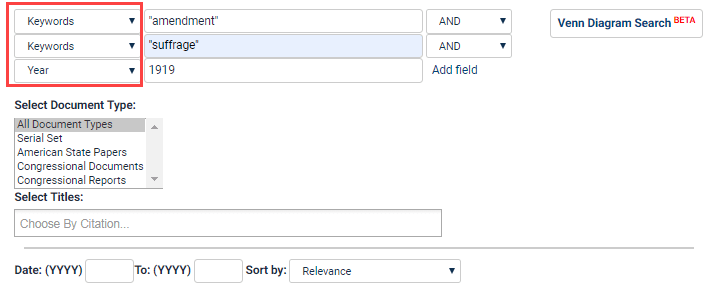

Users can find the House Report and minority views on the proposal for a nineteenth amendment in the Serial Set, as well. Perform an Advanced Search from HeinOnline’s Serial Set home page by selecting the blue hyperlink under the main search bar. Change the drop-down boxes to search by keywords and year. In the Keyword search boxes, type “amendment” and “suffrage.” In the box next to Year, type “1919.” Select the Search button to view the amendment proposal as the first result.

Help Us Complete the Project

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us in completing this project, please contact Shannon Hein at 716-882-2600 or shein@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give a special thanks to Wayne State University, University of Utah, and UC Hastings for their generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

We will continue to need help from the library community to complete this project. Download an Excel file listing the missing volumes of the Serial Set below:

Check back next month to unveil another secret of the U.S. Congressional Serial Set with HeinOnline. While you wait, catch up on previous Secrets of the Serial Set.

For more great content, connect with us on our social media platforms: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.