Immigration continues to be a hot and controversial topic in U.S. news, particularly throughout the current presidential administration. Luckily, HeinOnline has gathered the most important U.S. immigration legislation into one unique database to help users stay on top of developments in relevant law and policy.

Immigration Law & Policy in the U.S.

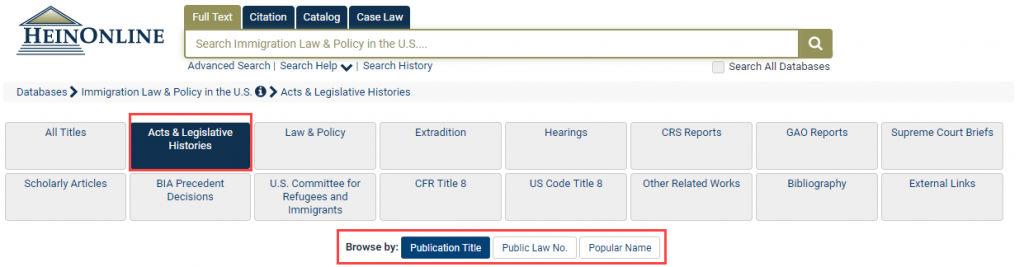

Since its release in April 2013, HeinOnline’s Immigration Law & Policy in the U.S. database has grown by more than 2,400 titles to include more than 3,000 volumes and 600,000 pages. The monumental collection is a compilation of the most important historical documents and legislation related to immigration in the United States, as well as current hearings, debates, and recent developments in immigration law. As the first-ever comprehensive immigration database, this compilation includes BIA Precedent Decisions, legislative histories, law and policy titles, extradition titles, scholarly articles, and more.

HeinOnline is also pleased to offer the following unique additions to this compilation:

- More than 200 immigration reports published by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) – New

- Two ceased serials (Refugee Reports and World Refugee Surveys) and more than 100 issue papers from the U.S. Committee for Refugees & Immigrants

- More than 450 congressional research service (CRS) reports related to immigration, including recent reports from the Trump Administration.

- More than 60 Supreme Court briefs related to immigration.

Join us in an exploration of immigration legislation, past and present, using HeinOnline’s authoritative collection. If you don’t yet subscribe to Immigration Law & Policy in the U.S., follow the link below to start a trial today.

Laws and Policies Through the Years

Early Immigration Legislation

Throughout the first century of U.S. history, anyone could move to the United States to live permanently without restrictions. This “open borders” policy allowed all emigrating persons from any country of origin to pay taxes, join the military, and conduct business. However, only those who underwent the naturalization process to become fully-fledged citizens could vote or hold elective office.

After the adoption of the U.S. Constitution in 1789, Congress utilized its new power to pass new naturalization legislation:

- The Naturalization Act of 1790 established that foreign-born residents of the United States could apply for citizenship provided they had lived in the U.S. for two years, had remained in their current residence for one year, and were free, white, and of “good moral character.” Later amendments to the act, including the Naturalization Act of 1795 and the Naturalization Act of 1798, went back and forth on the number of years required for residency.

Immigration in the 19th Century

The Naturalization Acts were further amended at the beginning of the 19th century:

- The Naturalization Law of 1802, whose provisions were canon until the mid-1900s, retained the “free white” requirement for citizenship, mandated a declaration of intent three years in advance, imposed a five-year residency requirement, and made considerations for native-born children of immigrants. Subsequent major naturalization legislation would not be introduced until more than a century later.

In the later 1800s, the U.S. turned its focus toward more than just naturalization law. Between 1850 and 1870, more than 200,000 immigrants entered the U.S. from China. In response, Congress passed several acts to limit the further entrance of immigrants from China or other East Asian countries.

- The Page Act of 1875 signaled the end of an “open borders” policy by barring “undesirable” immigrants, such as Chinese women who engaged in prostitution. This act made it difficult for any Chinese or East Asian woman to enter the United States, and thus effectively banned the immigration of all Chinese women to the country.

- The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 further banned all Chinese labor immigrants for ten years, regardless of sex. Expanding upon the Page Act, the Chinese Exclusion Act was the first U.S. law to exclude all immigrants from a specific ethnic or national group.

- The Geary Act built upon the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1892 after the latter’s ten-year period had come to a close. The law renewed the Chinese Exclusion Act for another ten years, and further required that all Chinese residents carry a permit as proof of residence. Violations of this law were punishable by deportation or a year of penal labor. After another ten years, the Geary Act would be renewed with no terminal date.

20th Century Developments

Pre–World War II

The early 1900s witnessed a steady rise in immigration, with more than 13 million immigrants living in the United States by 1910. In response, Congress passed increasingly restrictive immigration legislation.

- The Immigration Act of 1917, the most restrictive immigration legislation to date, was passed by a significant majority, even overriding a veto from President Woodrow Wilson. The law excluded immigrants who were (1) illiterate and over the age of sixteen, (2) “mentally defective” (a label which included homosexuals), and (3) originating from the “Asiatic barred zone” which included much of Asia and the Pacific Islands (with the exception of Japan and the Philippines).

- The Emergency Quota Act placed numerical limits on immigration for the first time in U.S. history in 1921. Quotas were established for each nationality and country, based on the number of foreign-born residents of each nationality living in the United States at the time. This act successfully restricted the immigration of poorly represented populations at the time, including Italians, Jews, Greeks, Poles, and other Slavs.

- The Immigration Act of 1924 made the quota system of the previous act permanent, though it was originally intended to be temporary. Established to preserve American homogeneity, quotas limited immigration from the Eastern Hemisphere, prevented any immigration from Asia, and did not apply to immigrants from the Western Hemisphere.

Post–World War II

Early 20th century laws which had focused on preserving the American identity were later amended and, at times, repealed and replaced with acts that removed restrictions and quotas, defined refugee status, and considered family reunification a priority.

- The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 compiled and codified existing immigration laws into one comprehensive text. For the first time, the law eliminated racial restrictions from U.S. immigration legislation by removing the exclusion of Asian immigrants. The act did, however, retain established quota systems for various regions and nationalities. In addition, the law established an employment-based preference system for admitting immigrants with education, relevant skills, and economic potential. To this day, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 remains the foundation of Title 8 of the U.S. Code.

- The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 and its amendments later abolished the system of national-origin quotas. The law also placed a worldwide limitation on immigration, including immigrants from the Western Hemisphere for the first time. The previous preference system was amended to include seven categories, considering as priorities relatives of U.S. residents and applicants with specialized skills. The act significantly increased the total number of immigrants to the United States, particularly from Asia and Africa.

Users can view legislative histories of these two monumental acts in the Immigration Law & Policy database. From the database home page, select the tab entitled Acts & Legislative Histories. Browse by Publication Title, Public Law Number, or Popular Name to view the complete legislative history of the Immigration and Nationality Acts and their amendments.

Refugee status was defined and elaborated upon in the 1980s:

- The Refugee Act of 1980 was passed to provide a permanent system for the admission of refugees to the United States, and to offer provisions for their resettlement. The act also redefined “refugee” to reflect the definition established by the United Nations, raised the number of accepted refugees per year to 50,000, and offered emergency procedures in the event that the number of refugees per year exceeds 50,000.

Immigration reform in the 1990s further contributed to an increase in legal entry to the United States:

- The Immigration Act of 1990 expanded and modified the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, significantly increasing the total immigration limit to 700,000 immigrants per year for two years, and 675,000 per year after that. The act created a number of new provisions in the name of immigration reform, including family-based and employment-based visas (categorized by occupation), a diversity visa program, and a temporary protected status visa. The act also removed English literacy testing in the naturalization process for certain residents over the age of 55 and eliminated the exclusion of homosexuals. View the legislative history of this important act in HeinOnline’s Immigration Law & Policy database.

While mid-to-late century legislation opened the doors for increased legal immigration, laws regarding illegal immigration and its punishment became a focus, as well.

- The Immigration Reform and Control Act, in 1986, became the first legislation mandating penalties for employers who knowingly hire illegal aliens. View the act’s legislative history here.

- The Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act added to the number of crimes for which an immigrant could be deported. The latter focused as well on authorizing the construction of fencing near San Diego, California, and increasing the number of immigration officers dedicated to enforcing immigration law. Civil penalties were introduced for attempted illegal border crossings. Both laws have, in part, been the cause of 2 million individual deportations from the United States since 1996.

Contemporary Immigration Laws and Policies

The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 exposed several weak points in the U.S. immigration system, subsequently affecting the American perspective on immigration. Security and visa processing became major concerns throughout all borders of the United States, land and sea.

- The Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act in 2002 called for a new data system containing information which would be used to determine the eligibility of prospective immigrants. Due to delays in developing the biometric-based systems required, portions of the act have not yet been implemented.

- The Secure Fence Act of 2006 introduced new security measures along land and sea borders of the United States to discourage illegal immigration. Surveillance systems, both ground-based and aerial, were implemented on all borders. The act also required that 700 miles of fencing be built along the southern border between the United States and Mexico.

In recent Presidential administrations, executive actions regarding immigration have been particularly popular. President Barack Obama signed two executive actions to institute the policies of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA). DACA allowed individuals brought to the United States illegally by their parents to receive a renewable two-year period of deferment from deportation. DAPA would have granted a “deferred action status” to undocumented immigrant parents of legal residents but was prevented from going into effect.

Users can find a host of results relating to these two policies in HeinOnline’s immigration database by entering “Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals” OR “Deferred Action for Parents of U.S. Citizens and Lawful Permanent Residents” into the main search bar on the home page.

President Donald Trump has additionally signed a number of executive orders during his administration with regard to immigration:

- “Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements” ordered the construction of a physical wall along the border of the U.S. and Mexico to prevent further illegal immigration.

- “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States” prioritized the deportation of immigrants convicted of any crime, including minor offenses, and imposed penalties on “sanctuary cities.”

- “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States” suspended the entry of immigrants from Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen for 90 days, the entry of refugees from Syria for an indefinite amount of time, and the entry of all refugees for 120 days.

Keep up with current developments in U.S. immigration as HeinOnline continues to grow its Immigration Law & Policy compilations.

Enjoy learning about the context of hot topics? Curious about the other special collections offered in HeinOnline? Smash that Subscribe button to the upper right of this post to stay in the know.

Don’t forget to connect with HeinOnline on our social media platforms: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.