This month, HeinOnline continues its Secrets of the Serial Set series by exploring one of the largest and most challenging engineering projects ever undertaken: the Panama Canal.

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative monthly blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Join us each month to explore notable events in U.S. history using the primary sources themselves. Grab a seat and prepare to be blown away by what the Serial Set has to offer.

About the Serial Set

The United States Congressional Serial Set is considered an essential publication for studying American history. Spanning more than two centuries with more than 17,000 bound volumes, the records in this series include House and Senate documents, House and Senate reports, and much more. Documents cover a wide variety of topics, including reports of executive departments and independent organizations, reports of special investigations made for Congress, and annual reports of non-governmental organizations. The Serial Set began publication in 1817 with the 15th Congress, 1st session. U.S. Congressional documents prior to 1817 are published as the American State Papers.

The Serial Set in HeinOnline

The Serial Set is an ongoing project in HeinOnline with the goal of adding approximately four million pages each year until the archive is completed. Since its initial release in October 2018, more than 3 million pages and nearly 4,400 volumes have been added to the Serial Set. In the past month alone, nearly 400 volumes and 250,000 pages were added.

As of August 2019, HeinOnline currently includes:

- Complete indexing of the more than 17,000 volumes of the Serial Set

- Full 40-year (1978-2018) content archive in HeinOnline’s image-based PDF format

- Complete coverage of the American State Papers

- 87% of the Serial Set available in HeinOnline or via links to HathiTrust Digital Library

The Serial Set is included at no additional charge for subscribers of HeinOnline Academic, HeinOnline Core+, and HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. Learn more about the Serial Set, how to use the online version, and how to contribute to the project by following the link below to HeinOnline’s Serial Set LibGuide.

What Is the Panama Canal?

The Panama Canal is an artificial waterway across the Isthmus of Panama, extending 51 miles to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Since its opening in 1914, the canal has enabled maritime vessels to travel between the oceans much more quickly and safely than by alternative routes around the southern tip of South America.

The Atlantic and Pacific Oceans lie at different geographic sea levels. In order to make it from one end of the canal to the others, vessels must somehow be raised above the Panamanian terrain. With the help of enormous water lock gates, ships entering on one end are lifted 85 feet above sea level, and at the other end, are dropped back down to sea level. Think that’s cool? Watch this time-lapse of a ship passing through the canal to really understand how it works:

As a U.S. territory and project, the canal played a vital role in the country’s economic success and military strategy. Today, as a territory of Panama, the canal still remains essential to efficient and cost-effective worldwide maritime trade. In addition to being a time, energy, and money saver, the canal has been saving the environment as well. By significantly reducing cargo movements and recently increasing cargo-carrying capacity, the canal consistently reduces emissions and fuel consumption. Considered one of the “greenest” routes for maritime trade, the canal has led to the reduction of more than 750 million tons of CO2 since 1914.

Building the Canal: Conception to Execution

Origins of the Idea

For hundreds of years, colonists, traders, and politicians recognized the value potential in creating a shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. In the Serial Set, users can find talk of an interocean canal as early as the 1830s, as evidenced by this report from the Committee on Roads and Canals from 1839. Before proposing its own project, the United States considered the canals undertaken by other countries and noted that the Central American countries of Panama and Nicaragua seemed promising for such a waterway.

By the mid-1800s, advances in technology and pressure to increase trade efficiency led to plans for a British canal across the Isthmus of Darien (now known as the Isthmus of Panama). Movements toward a Central American canal was of great interest to the United States, so Congress made sure to be kept apprised of British efforts when they began in 1846.

In December of the same year, the United States negotiated the Mallarino-Bidlack Treaty with New Granada, granting the U.S. transit and military rights in the Isthmus of Panama. A few years later, the United States initiated the construction of a Panama Railroad across the isthmus. Formally opened in 1855, the Panama Railroad greatly increased the efficiency of trade and helped to determine the structure of the later canal.

The United States vs. European Powers

The success of the Panama Railroad increased interest in an artificial waterway to further facilitate trade. In the decades following the railway’s opening, the United States launched several engineering expeditions and surveys into the Isthmus of Panama and other Central American locations to determine the most feasible site. Meanwhile, other countries started to be interested in a Central American canal once again.

Following its successful construction of the Suez Canal in Egypt, the French government set its sights on Panama. The United States initially considered this move from France hostile and in violation of the Monroe doctrine. After resolving to ensure the political neutrality of any Panamanian canal, whether European or American, the United States relinquished the Isthmus of Panama to the French and moved on to pursue a Nicaraguan canal instead. Nevertheless, the U.S. Congress still received reports on the French Panama Canal project.

The construction of a Panama Canal proved to be much more challenging than that of the Suez. Unlike in Egypt, French engineers had no predetermined ancient route to model and were at the mercy of a harsh climate and deadly tropical diseases. These challenges, combined with a lack of engineering expertise, led to the bankruptcy of the French endeavor in 1889, and work on the project was ceased.

Acquiring the Land

Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States at the time, touted the strategic benefit that would come from an American-controlled Panama canal. After France abandoned the project, Congress voted in favor of the Spooner Act of 1902 authorizing Roosevelt $40 million to pursue Panama as an option once again.

With this authorization, the United States signed the Hay-Herrán Treaty, granting the country a renewable lease from Colombia on the land in question. Though approved by the U.S. Senate, the Senate of Colombia never ratified the treaty. Refusing to renegotiate, Roosevelt refocused his efforts on providing political and military support to a rising revolution against Colombia for Panamanian independence.

In November of 1903, following a successful revolution, the United States signed the Hay-Bunau-Varilla treaty with the newly established Panamanian government, granting the United States the rights to construct and control the Panama Canal Zone. Read Roosevelt’s reasoning for discarding the Nicaraguan project, as well as his description of the revolution and treaty, in the President’s Annual Message, 1903. Though the treaty was considered an act of war on Colombia by some in the United States, the Panama Canal and its future successes can be directly attributed to Roosevelt’s actions.

Constructing the Canal

The United States launched its Panama Canal project in 1904. To oversee construction and control the Panama Canal Zone, Roosevelt established the Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC), led by Secretary of War William Howard Taft. Two plans for the canal were submitted—a sea-level plan (similar to the early French design) and a high-level lock plan. The sea-level plan initially won the majority views, but evidenced immediate problems when executed. Newly hired engineer John Stevens argued adamantly for a lock system, better equipment, and adjustments to the existing railroad in order to work around the issues. Read the descriptions of both plans as well as the majority and minority views of the 59th Congress, 1st Session.

Ultimately, the canal was designed with a lock system to raise and lower passing ships, which involved the creation of the world’s largest dam and largest man-made lake of the time. To construct such a system required the excavation of nearly 240 million cubic yards of material and the addition of 3.4 million cubic meters of concrete to build the locks. In addition, the plan required the explosion of the Gamboa Dike near the Culebra Cut, a preexisting continental divide between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. After upgrading old French equipment to allow for faster and larger-scale work, and then excavating and building for almost a decade, the Gamboa Dike explosion was the final obstacle to the canal project. Triggered in October of 1913 by President Woodrow Wilson, the explosion flooded the Culebra Cut and effectively opened the canal for transit.

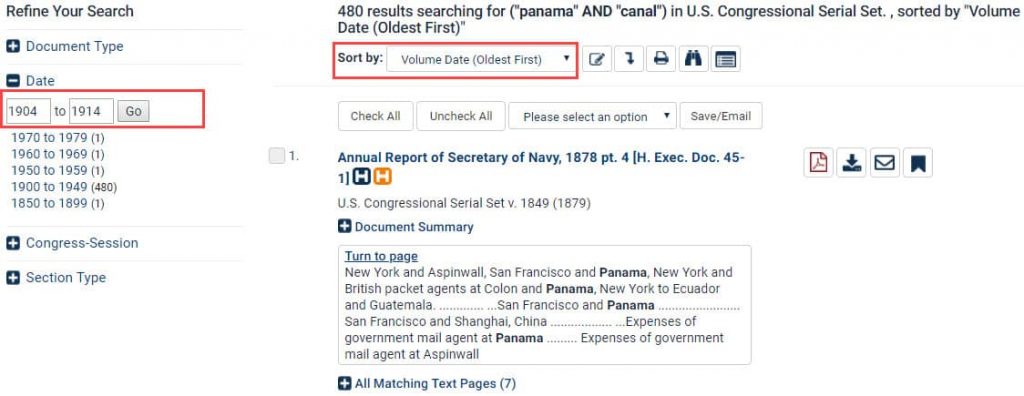

On August 15, 1914, the canal formally opened with the passage of the SS Ancon, after costing nearly $500 million (equivalent to about $9 billion today) and the lives of an estimated 5,600 workers. To view a number of documents relating to the finances, plans, and political ramifications of the canal project, simply enter “panama” AND “canal” into the main search bar of HeinOnline’s Serial Set. Limit the date range between 1904 and 1914, the length of the project, and sort results by “Volume Date (Oldest First).” Relevant results include:

- Temporary government of Panama Canal Zone (1903)

- Plan of ship canal to be constructed in Panama Canal Zone (1905)

- Increasing cost of construction of Panama Canal (1908)

- Defenses of Panama Canal (1909)

- Effect of Panama Canal on sea traffic (1913)

Post-Construction

For more than 60 years after its construction, the Panama Canal and its surrounding area were administered and controlled by the United States. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter signed the Torrijos-Carter Treaties, superseding the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty from 1903. The treaties gradually transferred control to Panama over a 20-year period, with the country taking increased responsibility for operations each year until 1999. The transfer of the canal to Panama was controversial in the United States, and the treaties only just passed in the Senate with two-thirds of the vote. View the treaties as proposed to the 96th Congress, 1st Session. By December 31, 1999, the United States completely withdrew its control of the Panama Canal. Today, the canal is administered by the Panama Canal Authority.

Help Us Complete the Project

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us in completing this project, please contact Shannon Hein at 716-882-2600 or shein@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give a special thanks to the following libraries for their generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

- Wayne State University

- University of Utah

- UC Hastings

- University of Montana

- Law Library of Louisiana

- George Washington University

We will continue to need help from the library community to complete this project. Download an Excel file listing the missing volumes of the Serial Set below:

Check back next month to unveil another secret of the U.S. Congressional Serial Set with HeinOnline. While you wait, catch up on previous Secrets of the Serial Set.

For more great content, connect with us on our social media platforms: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.