This month, history was made when Donald J. Trump became the third U.S. president to be impeached by the House of Representatives. However, contrary to popular misunderstanding, impeachment does not necessarily mean Trump will be removed from office.

Confused about how it all works? Keep reading for a step-by-step guide to impeachment through the lens of the recent Trump inquiry.

What Is Impeachment?

Impeachment was included by the framers of the U.S. Constitution as a way to protect the young nation from corrupt and tyrannical leadership. As laid out in Article II, Section 4, grounds for impeachment include “treason,” “bribery,” and “other high crimes and misdemeanors.” Though the Constitution does not provide a definition for the latter, the most common interpretation is that the term “misdemeanors” does not necessarily refer to criminal acts.

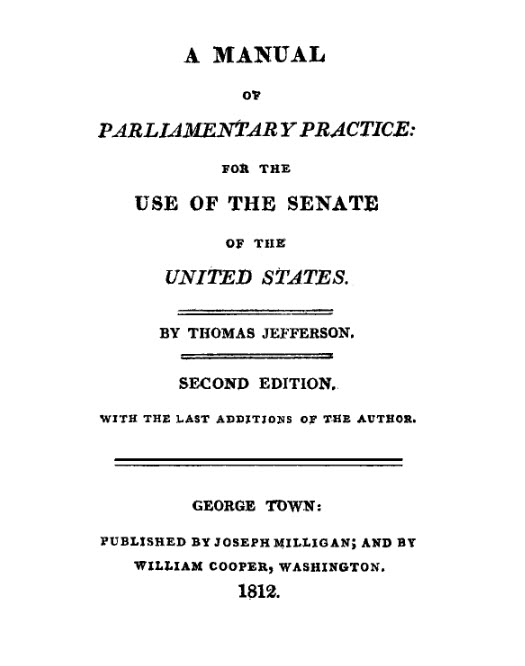

The privilege of impeachment begins with the House of Representatives of the United States Congress. According to Thomas Jefferson in A Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States, the impeachment of a federal official may commence in the House in a number of ways: (1) charges made on the House floor; (2) a House member’s resolution; (3) a message from the president; and (4) from facts discovered by a House investigation. Once impeachment has been initiated, there is little in the Constitution regarding House procedure for investigation and other proceedings, leaving the body to establish its own rules.

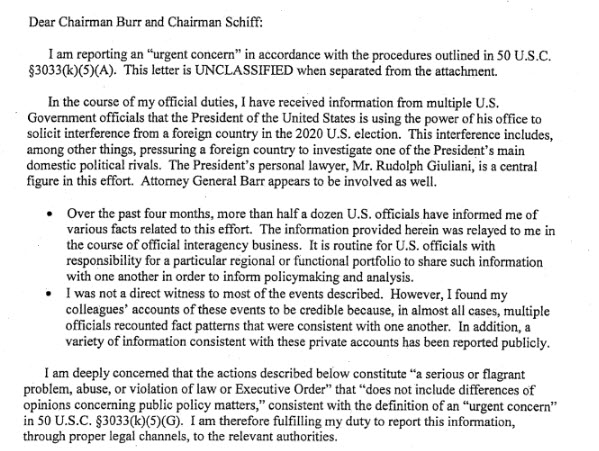

Step 1: A Formal Accusation

In Trump’s case, his impeachment proceedings stemmed from an anonymous accusation within the federal government. On August 12, 2019, in accordance with the Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protection Act, an unnamed intelligence official submitted a formal complaint that Trump may be abusing the power of the presidency. The letter alleged that Trump was withholding military aid to the war-torn country of Ukraine in order to pressure newly elected president Volodymyr Zelensky into interfering in the next U.S. election. Evidence of the allegations came from Trump’s initial withholding of aid and later phone call to Zelensky, in which he reportedly pressured the Ukrainian president to perform two election-related favors.

Step 2: Impeachment Inquiry and Investigation

The whistleblower’s complaint was made public and released to Congress in September, after which Trump reinstated the aid to Ukraine. Executing the privilege of the House, Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced a formal impeachment inquiry into President Trump on September 24. On the same day, Trump released a declassified and non-verbatim transcript of the July 25 phone call.

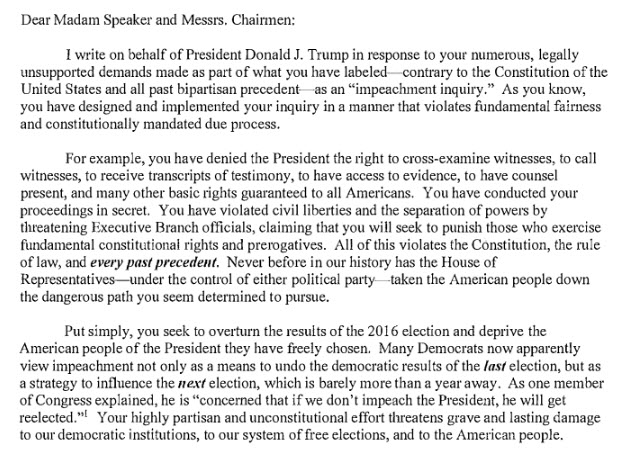

The next step for Congress was to launch an investigation into Trump’s potential impeachment, the findings of which would be presented in a final report to be voted on in the House. Throughout the fall of 2019, the House issued subpoenas for federal documents from several federal entities, including the White House. Regardless, the White House refused to provide the requested documents.

As part of its investigation, the House also held several closed-door and public hearings, requesting the appearance of more than 20 witnesses who could provide information on Trump’s relationship with Ukraine. Though some refused to appear or were blocked from appearing by the White House, more than a dozen complied. Read their depositions below:

- Bill Taylor, a U.S. diplomat in Ukraine.

- George Kent, a State Department official overseeing Ukraine policy.

- Maria Yovanovitch, a former Ukrainian ambassador.

- Alexander Vindman, the Director of European Affairs at the National Security Council.

- Jennifer Williams, special advisor to Mike Pence.

- Gordon Sondland, a U.S. ambassador to the European Union.

- Laura Cooper, a deputy assistant secretary at the Department of Defense.

- David Hale, the Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs at the State Department.

- Fiona Hill, the former Senior Director for Europe and Russia on the National Security Council.

- David Holmes, a political counselor at the U.S. Embassy in Kiev.

- Christopher Anderson, a deputy to Special Envoy for Ukraine Kurt Volker.

- Catherine Croft, a State Department specialist on Ukraine.

- Tim Morrison, a former National Security Council official.

Republican representatives provided a list of witnesses from whom they wished to hear testimony. Concerned that the witness list was an attempt to further investigate the Bidens and the 2016 election, House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff rejected the requests.

In early December, a draft of Chairman Schiff’s 300-page investigation report was distributed throughout the House Intelligence Committee and released to the public. The report concluded that President Trump “personally and acting through agents within and outside of the U.S. government, solicited the interference of a foreign government, Ukraine, to benefit his reelection.” On December 3, the House Intelligence Committee voted in favor of adopting the final report and sent it to the House Judiciary Committee, who would decide whether or not to recommend impeachment.

Two days later, Speaker Pelosi authorized the House Judiciary Committee to begin drafting articles of impeachment. The Judiciary Committee then held its own set of impeachment hearings, inviting Trump and his legal team to attend, though the president declined. On December 10, 2019, the Committee announced two articles of impeachment against President Trump: (1) abuse of power and (2) obstruction of justice.

Step 3: A Vote in the House of Representatives

In essence, articles of impeachment are a set of charges against an individual, as an indictment is to criminal law. However, articles of impeachment are not necessarily crimes and do not directly result in the removal of an individual from office. Once drafted, articles of impeachment against the president must be voted on by the House of Representatives.

On December 18, the House held its formal impeachment vote against Donald Trump. By 8:30pm, after a full day of debate, both articles—abuse of power and obstruction of justice—were passed, and Trump became the third U.S. president to be impeached.

Step 4: A Trial in the Senate

After impeachment has been approved by the House, it is incumbent upon the Senate to hold an impeachment trial (see Article I, Section 3, Clause 6 of the U.S. Constitution). Much like criminal trials in the United States, the Senate trial is presided over by a judge—the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (currently John G. Roberts, Jr). The president and his legal counsel sit on the defense, while the “prosecution” consists of members of the House (called “managers”). Each side is given the right to call and cross-examine witnesses. Meanwhile, senators act as the “jury,” listening to the evidence for conviction presented by the House before drawing their conclusions.

Following their deliberations, the senators will hold a vote on whether the president is guilty or not guilty. A guilty verdict—requiring a two-thirds vote in the Senate—would remove President Trump from office, resulting in Vice President Mike Pence assuming the presidency. Should Mike Pence be unable to take office for some reason, the line of succession laid out by the Presidential Succession Act is as follows:

- Speaker of the House of Representatives (Nancy Pelosi)

- President pro tempore of the Senate (Charles Grassley)

- Secretary of State (Mike Pompeo)

- The remaining 14 presidential Cabinet members in the order of when their departments were created.

As the Senate is not trying the president on legal charges, Trump would not be convicted of any crime and would therefore suffer no other penalty than removal.

To initiate the trial, the articles of impeachment must be submitted to the Senate by the House. As the Senate makes its preparations, the House maintains possession of the articles until it can ensure that a fair trial will be conducted. With the legislative branch closed for its winter break, it is unclear when Trump’s impeachment trial will commence.

Historically, only two presidential impeachment proceedings have made it to trial—those for President Andrew Johnson and for President Bill Clinton. Neither president was convicted and thus each remained in office for the remainder of their terms. While it is unlikely that the Republican-held Senate will convict Donald Trump, it is possible that he could be the first president in U.S. history to be impeached, convicted, and removed from office.

Want to Learn More?

Interested in digging deeper into President Trump’s impeachment? Educate yourself on the topic with these related blog posts:

- Researching Impeachment in HeinOnline

- Trump’s Impeachment Hearing: The Testifying Scholars Revealed

- The Impeachment of Bill Clinton

Learn about hot topics, historical events, HeinOnline updates, and more by subscribing to the HeinOnline Blog today.