This month, HeinOnline continues its Secrets of the Serial Set series by exploring the prohibition of alcohol in the United States.

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative monthly blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Join us each month to explore notable events in U.S. history using the primary sources themselves. Grab a seat and prepare to be blown away by what the Serial Set has to offer.

About the Serial Set

The United States Congressional Serial Set is considered an essential publication for studying American history. Spanning more than two centuries with more than 17,000 bound volumes, the records in this series include House and Senate documents, House and Senate reports, and much more. The Serial Set began publication in 1817 with the 15th Congress, 1st session. U.S. congressional documents prior to 1817 are published as the American State Papers.

The Serial Set is an ongoing project in HeinOnline, with the goal of adding approximately four million pages each year until the archive is completed. View the current status of HeinOnline’s Serial Set project by clicking the button below.

The Anti-Alcohol Movement

Origins of the Concept

The consumption of alcohol has been a topic steeped in controversy since colonial America. During this time, alcohol itself was not necessarily considered an unwholesome or dangerous substance. Society at large did condemn abuse of the drink, however, and legal options existed to dissuade alcohol-induced impropriety, like public drunkenness.

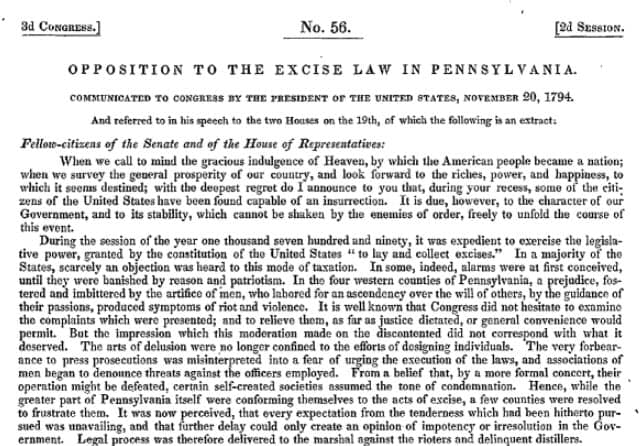

During the presidency of George Washington, the newly formed United States government imposed a tax on all distilled spirits which eventually became known as the “whiskey tax.” Though intended to mitigate government debt which had been accrued during the Revolutionary War, the tax was endorsed by anti-alcohol activists of the time. Despite established support, the rest of the country resisted the tax in one of the first significant tests of the young government—the Whiskey Rebellion. Read George Washington’s message to the 3rd Congress, 2nd session regarding the Whiskey Rebellion.

Development of the Movement

Following the repeal of the whiskey tax in the early 1800s, small temperance groups began to form in a number of states to protest the consumption of alcohol. By 1826, the American Temperance Society had formed, reaching 1.5 million members in less than 10 years. The movement achieved its first true success in 1851 when the state of Maine instituted a ban on the manufacture and sale of liquor; however, the legislation would be repealed only 5 years later.

When calls for the abolition of slavery grew louder over the next few decades, the temperance movement slowly lost steam. After the Civil War was won, however, social activists from diverse backgrounds joined the cause—doctors, pastors, businessmen, eugenicists, and Klansmen all found a reason to support the prohibition of alcohol. The temperance movement also became a vehicle for women to engage in politics, promoting abstinence from alcohol as a method of remaining “pure” and for preventing domestic abuse. As the movement made its resurgence, the word “temperance” soon extended beyond abstinence from alcohol to include the condemnation of related behaviors and alcohol-serving establishments.

In 1881, Kansas became the first state to incorporate an alcohol ban into its constitution. Carrie Nation, a radical member of the anti-alcohol movement, decided to enforce the ban by attacking saloons and other alcohol-serving businesses with a hatchet. Meanwhile, the courts took a more logical approach to debating the alcohol controversy. Many, as in Mugler v. Kansas, reached the same conclusion—the consumption of alcohol was a danger to public health, safety, and moral values.

Nationwide Prohibition of Alcohol

Federal Action

By the early 1900s, the idea of a nationwide prohibition of alcohol had become a significant matter of debate in Congress. Browse a compilation of papers relating to the congressional prohibition debate, including Senate reports on the subject which date back to the 1880s. Further, read an argument for prohibition curated and presented by orator and politician William Jennings Bryan in 1915.

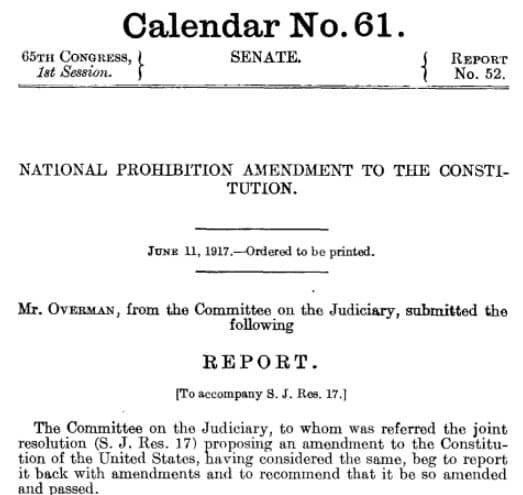

When the 65th Congress convened in March of 1917, a new concern was on the horizon—the United States’ entry into World War I. On April 6, the U.S. declared war on Germany, formally joining the fray. Proponents of prohibition in Congress—outnumbering the opposition 140 to 64—saw a new justification for a national alcohol ban: limiting the production of alcohol would allocate more resources, like grain, to the war. In June of the same year, the nationwide prohibition of alcohol was proposed as a constitutional amendment and ultimately passed in both houses by December.

Though intended to save grain for the war, the amendment was not ratified until after the war had concluded, in January 1919. Regardless, the prohibition of alcohol was added to the U.S. Constitution as the 18th Amendment, prohibiting the production and sale (but not consumption) of “intoxicating liquors.” To outline the penalties for violating the new amendment, Congress passed the National Prohibition Act, despite President Woodrow Wilson’s veto. Defining liquor as any drink containing 0.5% or more alcohol by volume, the act effectively banned all liquor, wine, and beer in the country. As laid out by the act, the United States went “dry” on January 17, 1920.

Controversy and Anti-Prohibition Efforts

The restrictions outlined in the act took many around the country by surprise, including even proponents of Prohibition. The topic became widely controversial, particularly in the medical profession. Their prescription of choice eradicated, contemporary doctors began to lobby for the repeal of Prohibition, leading Congress to debate the medicinal value of beer and wine in 1921.

At the same time, Americans found increasingly creative ways to undermine the 18th Amendment and the National Prohibition Act. Hoarding alcohol for home consumption became widespread, with even Presidents Woodrow Wilson and Warren G. Harding transferring their ample alcohol supplies in and out of the White House. Americans soon began leveraging the loopholes inherent in prohibition legislation—for example, since grape juice had not been banned, individuals began fermenting the juice in their own makeshift home distilleries.

Though “bootlegging” now invokes thoughts of stolen music or movies, the term became popularized during the Prohibition era. With alcohol legal in Canada and Mexico, it became common practice to buy wine, beer, or liquor there and sell it in the States from flasks hidden in one’s bootleg. Another bootlegger method included stealing industrial alcohols (which had not been banned) and reselling them as beverages. This practice became so prevalent that the Treasury Department ordered manufacturers to poison industrial alcohols with additives, creating “denatured alcohol” to discourage consumption. When bootlegging chemists found ways to renature the alcohol, even deadlier poisons were added and regulations on denatured alcohol increased. All in all, it is estimated that approximately 10,000 people were killed by drinking denatured alcohol during this time period.

Repealing the Amendment

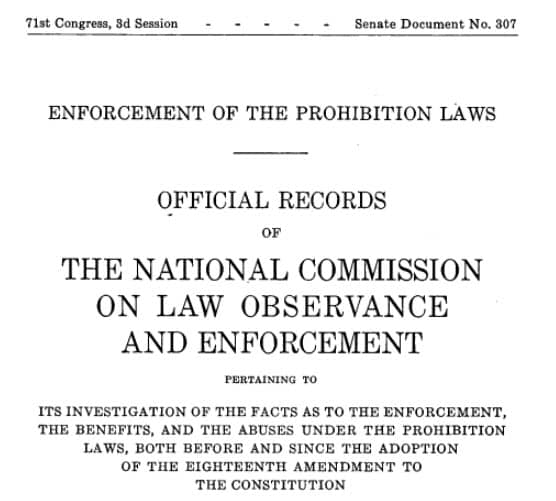

In 1929, President Herbert Hoover established the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement to evaluate the widespread violation of national alcohol prohibition and the enforcement efforts of the U.S. criminal justice system. In its findings, the commission uncovered questionable police interrogation tactics, observed a general American contempt for prohibition, and reported a widespread violation of prohibition legislation. Peruse the five volumes containing official records of the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement.

In 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt campaigned for the presidency, partly on a platform to end this prohibition experiment. Anti-Prohibition organizations appeared, citing a negative economic impact due to the near eradication of the alcohol industry—one which had previously comprised 14% of federal, state, and local tax revenue. Activists also pointed to the expansion of organized and underground crime under Prohibition—in New York City alone, more than 30,000 speakeasies were serving illegal alcohol by the mid-1920s.

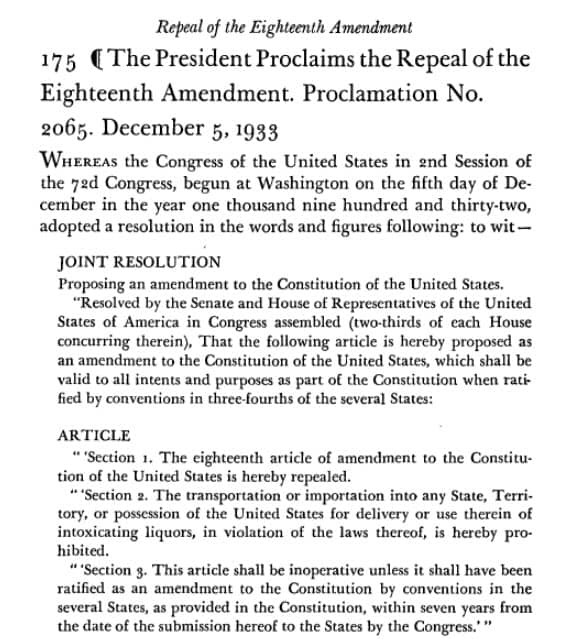

In early 1933, a resolution was proposed in Congress to repeal the 18th Amendment. While waiting for the new amendment’s ratification, President, Roosevelt signed into law the Cullen-Harrison Act within his first month as president. After legalizing beer and wine with an alcohol content of approximately 3.2% or lower, Roosevelt reportedly quipped, “I think this would be a good time for a beer.” A few months later, the 21st Amendment was ratified, repealing the 18th Amendment and ending Prohibition. Read President Roosevelt’s proclamation of the amendment’s repeal.

Help Us Complete the Project

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us, please contact Shannon Hein at 716-882-2600 or shein@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give a special thanks to the following libraries for their generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

- Wayne State University

- University of Utah

- UC Hastings

- University of Montana

- Law Library of Louisiana

- George Washington University

- University of Delaware

We will continue to need help from the library community to complete this project. Download an Excel file listing the missing volumes of the Serial Set below:

Check back next month to unveil another secret of the U.S. Congressional Serial Set with HeinOnline. While you wait, catch up on previous Secrets of the Serial Set. Alternatively, learn more about how to use HeinOnline’s Serial Set with our in-depth LibGuide.

For more great content, connect with us on our social media platforms: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.