The Boston Tea Party was a controversial political protest which escalated the tensions between the Kingdom of England and its American colonies and ultimately culminated in the Revolutionary War. Learn about the causes and effects of the protest, as well as the key players involved—many of whom would go on to play crucial roles in the formation of the United States.

Before We Get Started

1. World Constitutions Illustrated

This library enables legal scholars to research the constitutional and political development of every country in the world. It includes the current constitution for every country in its original language format and an English translation, as well as substantial constitutional histories for all countries. It also includes constitutional periodicals, thousands of classic books, other related works such as the World Factbook, links to scholarly articles and online resources, and bibliographic references.

2. U.S. Presidential Library

This library includes such titles as Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Public Papers of the Presidents, CFR Title 3 (Presidents), Daily and Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents, and other documents related to U.S. presidents.

3. U.S. Congressional Documents

Featuring the complete Congressional Record Bound version, along with the daily version back to 1980. This database also includes the three predecessor titles: Annals of Congress (1789-1824), Register of Debates (1824-1837), and Congressional Globe (1833-1873), as well as other important congressional material such as hearings, CRS Reports, and much more.

The Boston Tea Party

New World, New Colonies, and New Taxes

Following Columbus’ arrival in the Americas in 1492, the major powers of 15th-century Western Europe clamored to expand their influence there. In 1607, the Kingdom of England established its first permanent colony in Jamestown, Virginia. After discovering the profitability of American resources, the Jamestown colony flourished; in response, England sponsored several more colonization projects, including many to the region which would become known as New England.

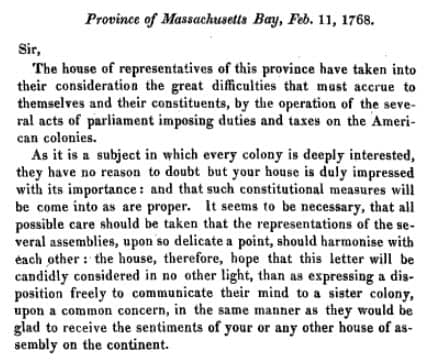

Over the years, however, colonists grew increasingly discontented with British rule. Without representation in Parliament, they felt that taxes and other laws undermined their constitutional rights. During its French and Indian War, in particular, England began to impose higher taxes on the colonists, to require that the colonists house British soldiers, and to restrict the expansion of American settlements. The Massachusetts Bay Colony felt the brunt of this legislation, leading to a tension which is evident in this letter from Samuel Adams and James Otis, Jr.

A Boycott of British Tea

Boycotting British goods (like tea) soon became a way to demonstrate American frustration with the Kingdom of England. Many colonists chose not to drink tea at all while others chose domestic alternatives or engaged in tea smuggling.

In 1773, plummeting tea sales and stockpiles of unwanted tea left the British East India Trading Company in a precarious financial situation. British Parliament responded to the crisis with the Tea Act, which eliminated the need for a “middle man” to greatly reduce the cost of British tea for American colonies. By undercutting the price of smuggled Dutch tea, Parliament hoped colonists would be more likely to buy British, and as a result, implicitly accept the idea that the Kingdom of England could impose taxes on its colonies.

A Tea Party to Remember

While the colonies digested the implications of the new act, the East India Company sent nearly 600,000 pounds of tea to Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and Charleston. Hearing of the incoming shipment, tea smugglers and members of the Whig party—at times referring to themselves as Sons of Liberty—attempted to spark protest. By the time the ships arrived in New York City, Philadelphia, and Charleston, protesters in those colonies had successfully convinced the consignees—individuals who receive the tea—to resign. The New York and Philadelphia ships returned to England still loaded with their entire cargo, while the tea in Charleston was claimed by customs personnel.

Protesters in Boston were unable to achieve the results of the other colonies. Governor Thomas Hutchinson was firmly in favor of the Tea Act, and his two sons were the Boston tea consignees. In late November, the first ship, Dartmouth, arrived and waited to be unloaded on schedule—under British law, ships must unload and pay their duties within 20 days of arrival. Instead, the citizens of Boston deliberated over the issue under the leadership of Samuel Adams, and 25 Boston men were sent to guard the ship. Meanwhile, two more ships arrived.

On December 16, the twentieth day after Dartmouth’s arrival, more than 5,000 people gathered at the Old South Meeting House. Upon learning that Governor Hutchinson would refuse to let the ships return without unloading or paying the duty, Adams lost control of the group.

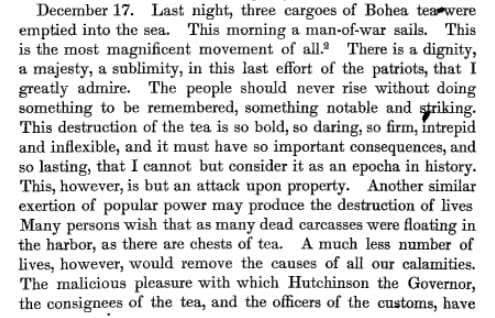

Later that night, a group of men—some dressed as Mohawk warriors—took matters into their own hands, stealing aboard the three ships and hurling all 342 chests of tea into the water. Read John Adams’ diary entry concerning the event that would later be known as the Boston Tea Party.

The Aftermath

Though Whigs like John Adams and Samuel Adams admired the act, others such as Benjamin Franklin and George Washington were appalled. In the eyes of the latter, the colonists had committed a grave injustice by destroying private property, a concept which they considered a sacred right.

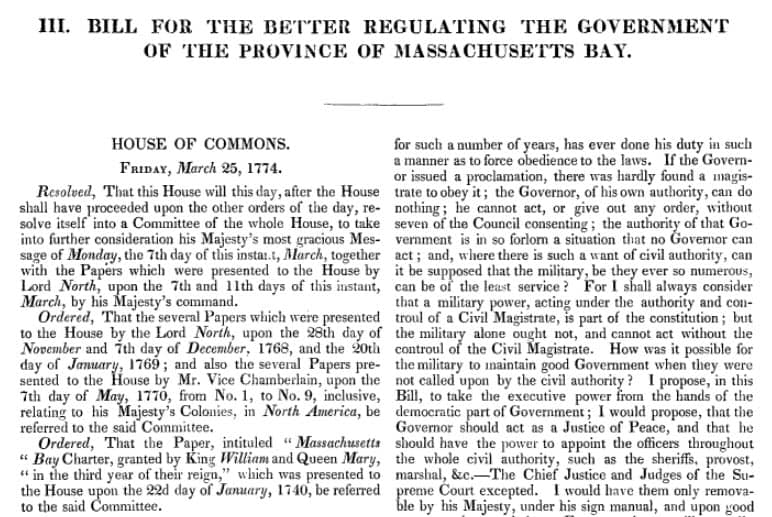

The Kingdom of England was even more displeased. In 1774, the kingdom passed the “Intolerable Acts,” legislation intended to punish Boston for its crime and restore the authority of British government in the colony. Seen later as violations of constitutional and human rights, the acts closed the port of Boston, changed the stipulations for trials, and eliminated the colony’s ability to self-govern.

The Intolerable Acts were reviled throughout the Thirteen Colonies, leading delegates from each to form the First Continental Congress. Convened in September of 1774, the Congress petitioned King George III to repeal the legislation as part of its Declaration and Resolves. England secretly prepared for war, but its efforts were discovered by the Boston militia, sparking the American Revolution in 1775. Learn more about the formation of the United States following the American Revolution.

Love to Learn?

At HeinOnline, we love to research topics of all shapes and sizes. We share that love on our blog by using HeinOnline databases to research anything and everything under the sun.

Don’t miss out! Receive this quality content right to your inbox by clicking Subscribe at the top of this post.