This month, HeinOnline continues its Secrets of the Serial Set series by investigating the 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger disaster.

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative monthly blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Join us each month to explore notable events in U.S. history using the primary sources themselves. Grab a seat and prepare to be blown away by what the Serial Set has to offer.

ABOUT THE SERIAL SET

The United States Congressional Serial Set is considered an essential publication for studying American history. Spanning more than two centuries with more than 17,000 bound volumes, the records in this series include House and Senate documents, House and Senate reports, and much more. The Serial Set began publication in 1817 with the 15th Congress, 1st session. U.S. congressional documents prior to 1817 are published as the American State Papers.

The Serial Set is an ongoing project in HeinOnline, with the goal of adding approximately four million pages each year until the archive is completed. View the current status of HeinOnline’s Serial Set project by clicking the button below.

A Media Event Gone Horribly Wrong

On a chilly Florida morning in 1986, a host of onlookers gathered at Cape Canaveral for the much-anticipated launch of Space Shuttle Challenger. Challenger was preparing for its tenth flight to undertake STS-51-L, a mission in part designed to inaugurate NASA’s widely publicized Teacher in Space Project (TISP). Millions turned to their televisions to watch the launch unfold, including a large number of schoolchildren eager to witness Christa McAuliffe, NASA’s teacher designee, make the journey to space.

As evidenced by the cheers from the crowd below, the initial launch seemed successful. However, smiles faded, replaced by looks of confusion, as a large fireball erupted in the sky less than a minute later. Unbeknownst to the excited onlookers, the orbiter had broken apart and all seven crew members—including Christa McAuliffe—had been killed. A joint in one of the spacecraft’s solid rocket boosters (SRBs) had failed at launch due to improper design and untested weather conditions. Aerodynamic forces proceeded to pull the orbiter apart, though it appeared to have exploded. At 11:38 a.m., the spacecraft disintegrated above the Atlantic Ocean as the crew cabin plummeted to the ocean surface.

Watch CNN’s live coverage of the Challenger launch and “explosion” below.

The “Explosion” Explained

A Critical Design Flaw

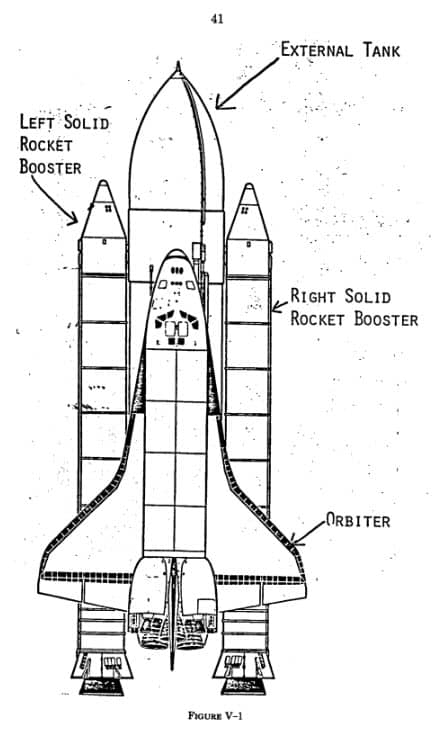

When the Space Shuttle Challenger was designed, it was equipped with two solid rocket boosters (SRBs) to provide the thrust necessary for an initial launch. Inside the boosters was burning solid propellant which produces hot, high-pressure gases. To contain that gas, field joints on the boosters were sealed by two rubber O-rings which would close more tightly against the forces generated at ignition. See a diagram of the boosters in relation to the shuttle.

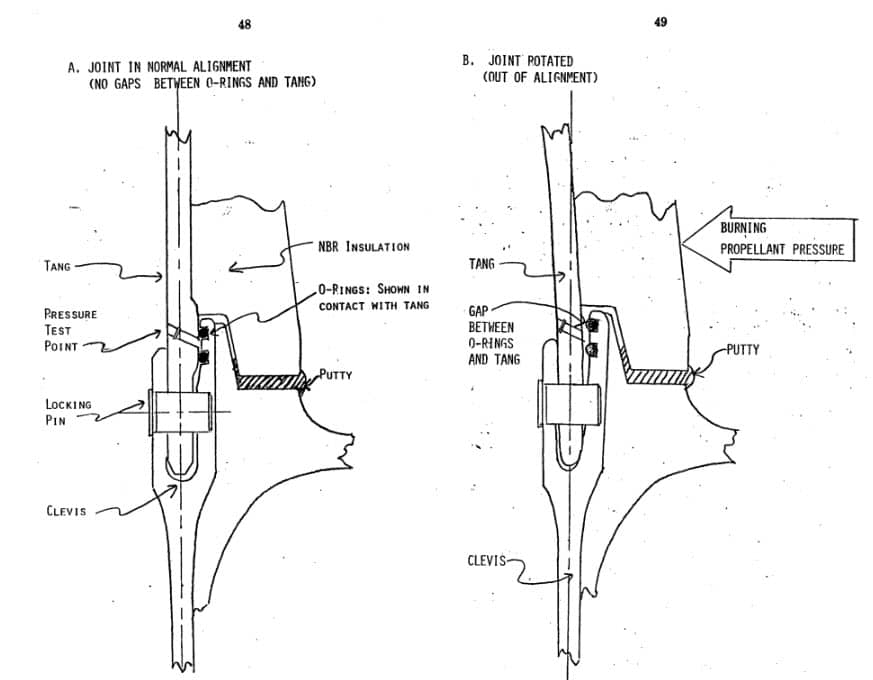

If the hot gases leaked, they could erode the O-rings, allowing for flame to escape and the joint to burst—events which could lead to the destruction of the booster and ultimately, the shuttle. See the comparison of a joint in normal alignment (with no O-ring gap), and a joint out of alignment.

With such a critical role, the O-rings should have been designed with extreme care and precision. However, nearly a decade before the disaster, contractor Morton-Thiokol had discovered the potential for a leak during a test of the joints. While many Morton-Thiokol engineers were adamant that the design was too flawed for flight, the SRB joints were nonetheless accepted by NASA in 1980.

Over several years of space shuttle missions, the O-rings came back with clear and consistent erosion. The parts were thus given the designation of “Criticality 1″—if they failed, the orbiter would be destroyed. Redesign commenced on the O-rings in 1985, but in the meantime, the shuttles that used them remained in flight. The O-ring erosion was considered an “acceptable risk.”

A Rush to Launch

Challenger‘s launch was rescheduled several times throughout January of 1986 due to bad weather and unrelated mechanical problems. After the date was pushed to January 28, the question became whether that morning’s forecast (30° F) was too low. Engineers had previously expressed concern about the effect of low temperatures on boosters, a warning which NASA personnel brought up to Thiokol.

The issue was brought to a teleconference between NASA and Morton-Thiokol on the eve of the launch. Thiokol engineers reiterated their concerns, emphasizing that with the O-rings at Criticality 1, there would be no backup if they should fail in the cold. NASA balked at the idea of postponing the launch any further and scheduled another conference without engineers present. Both NASA and Thiokol management decided to proceed with the launch as scheduled. Meanwhile, engineer Robert Ebeling went home and told his wife that if launched the next day, Challenger would explode.

When Challenger took off, engineers breathed a sigh of relief. However, though all appeared normal, ignition had caused one of the booster’s casings to swell, creating an opening for hot gases to escape. The rubber O-rings, hardened by the cold, couldn’t seal the gap in time. While aluminum oxides from the interior propellant did create a temporary seal, it was shattered by an unexpected burst of wind stronger than that experienced by any of the previous flights. Without any barriers, the hole in the joint quickly enlarged; flame burned through the joint, reaching the external tank.

The right booster detached from the external tank, which succumbed to structural failure. With its internal hydrogen and oxygen tanks no longer separated, the gases mixed and ignited to create a fireball. The tank disintegrated, altering Challenger‘s load factor, and ultimately tearing apart the orbiter. At this point, the crew may have remained uninjured; if the vehicle had an escape system, they may have even survived. Instead, the cabin detached from the shuttle, plummeting to the water at 207 mph—an unsurvivable impact.

Aftermath and Investigation

The White House Response

The hydrogen and oxygen combustion created a veil of smoke, blocking the reality of the situation from view. Regardless, NASA and Thiokol engineers knew exactly what had happened. NASA initiated its standard contingency procedure and launched a lengthy recovery operation which would last for months.

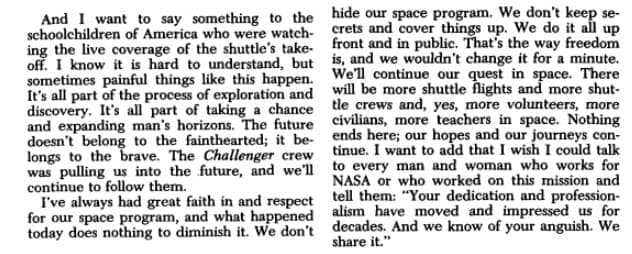

President Ronald Reagan, champion of the Teacher in Space Project, postponed his State of the Union Address to address the nation about the disaster. Read his speech, considered by many to be one of the most significant of the 20th century.

To investigate the disaster, Reagan initiated the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident (also known as the Rogers Commission). Notable members included astronaut Neil Armstrong as Vice Chairman as well as astronaut Sally Ride and theoretical physicist Richard Feynman. After several months, the Commission released its final report, determining the cause of the accident to be a failure of the O-rings due to improper design. Further contributing causes, the report found, included flawed NASA procedures and failure in communication between NASA and Morton-Thiokol.

An Investigation in the House

Following the report of the Rogers Commission, the U.S. House Committee on Science & Technology conducted its own investigation. Using the findings of the Commission as well as its own hearings, the Committee released its final report on October 29, 1986. Differing slightly from the Rogers report, it came to the same conclusion about the O-rings but attributed the accident to poor decision-making, rather than flawed procedure and communication.

Changes at NASA

The Rogers Commission offered several recommendations to improve the space shuttle program. To implement the changes, NASA placed the space shuttle program on a 32-month hiatus, initiated a total redesign of its solid rocket boosters, implemented a more realistic shuttle flight schedule, and created the Office of Safety, Reliability, and Quality Assurance.

Many remained critical of NASA’s changes, particularly after the subsequent Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003—another catastrophic accident in which seven more lives were lost. Critics believed that the same management issues which led to the Challenger accident were responsible. In 2011, the Space Shuttle Program was retired after Space Shuttle Atlantis flew its final flight.

Help Us Complete the Project

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us, please contact Shannon Hein at 716-882-2600 or shein@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give a special thanks to the following libraries for their generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

- Wayne State University

- University of Utah

- UC Hastings

- University of Montana

- Law Library of Louisiana

- George Washington University

- University of Delaware

We will continue to need help from the library community to complete this project. Download an Excel file listing the missing volumes of the Serial Set below: