Following years of political instability and violent rebellion, the Constituent Congress of Mexico approved a new Mexican constitution in 1917 that would promise expansive social reform and political reconstruction. The first such document in the world to outline social rights, the Mexican Constitution of 1917 has served as a model for the constitutions of other nations. Join us in discovering the origins of this historic document with HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated.

World Constitutions Illustrated

With historical and current constitutions from around the world, this essential database enables scholars to research the constitutional and political development of any country. The database includes the current constitution of every country in its original language, and often with at least one English translation. For every constitutional document, researchers can find the original text, amending laws, consolidated text, and important related texts. This database also includes historical constitutions, constitutional periodicals, thousands of classic books, other related works such as the World Factbook, links to scholarly articles and online resources, and bibliographic references.

Start your free trial to this essential resource for international research today!

A Near-Decade of Rebellion Sparks Political Change

From 1884 onward, one president ruled Mexico continuously, determined to establish domestic order to facilitate economic prosperity. Under the faςade of democracy, President Porfirio Díaz used coercion and co-optation to neutralize political competition, while silencing the media and controlling the court system to suppress civilian opposition.

By 1910, Díaz was nearly 80 years old, with no system in place for his succession. That same year, young and wealthy idealist Francisco Madero declared his intent to run against Díaz in the next election. Unable to control this election as he did others, Díaz became threatened by Madero’s increasingly successful campaign and subsequently had him arrested. Inevitably, Díaz “won” the presidency once again.

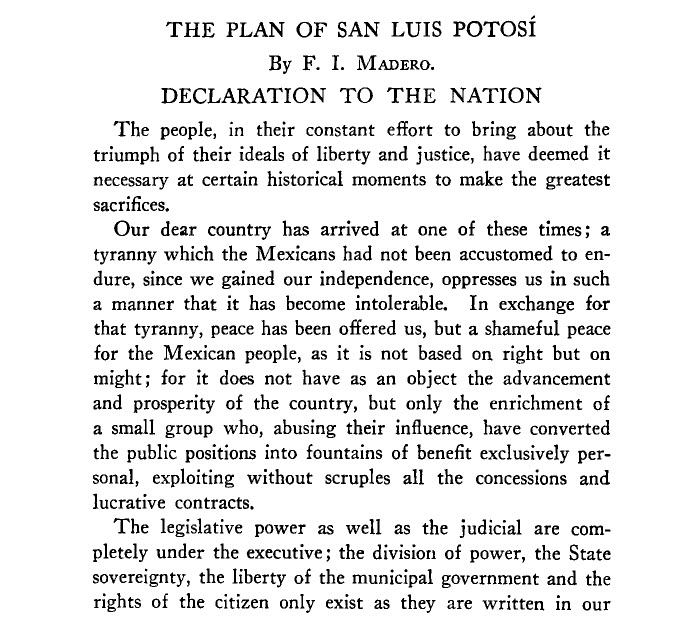

On October 5, 1910, Madero published a political manifesto known as the Plan of San Luis de Potosi, calling for a revolt against the Díaz regime. Many less fortunate Mexican citizens—including farmers, miners, and indigenous peoples—had felt oppressed by Díaz’s policies and found hope in Madero’s plan. Soon, spontaneous rebellions erupted across the country.

Bolstered by U.S. financiers and revolutionary leaders such as Pancho Villa, Emiliano Zapata, and Venustiano Carranza, these smaller regional rebellions grew to become serious threats. Within a few months, a series of battles had left the Mexican Federal Army defeated. On May 21, 1911, Madero and Díaz negotiated an agreement—Díaz and his vice president would step down and be exiled, and an interim president would be instituted as the country prepared for another presidential election. None of the social reforms central to Madero’s idealistic manifesto were incorporated into the treaty, however, and the structure of the Díaz regime remained largely intact.

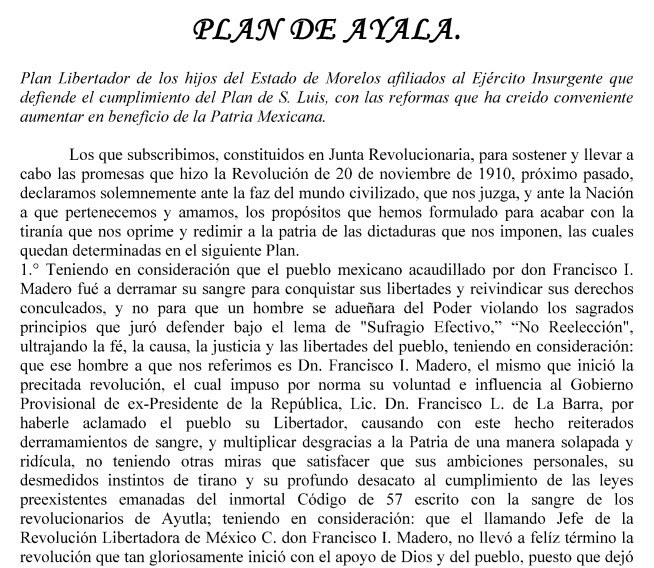

A nationwide hope for stability and change led to Madero’s official election to the presidency in October of 1911. During his time in office, however, Madero did not meet the high expectations of his country. Many felt betrayed, and some took up arms to express their frustration. Emiliano Zapata, who had previously helped lead the anti-Díaz revolution, ultimately declared rebellion against Madero in his Plan de Ayala.

Much as Díaz did before him, Madero relied on the Federal Army—and particularly one general, Victoriano Huerta—to suppress any revolts. Unbeknownst to Madero, however, Huerta had formed an alliance with the rebels. Furthermore, he had the support of the United States to become the next Mexican president. In pursuit of political power, the general allowed the rebels to take Mexico City, causing the Madero presidency to crumble. Madero and his vice president were forced to resign, but both were assassinated before they could be sent into exile.

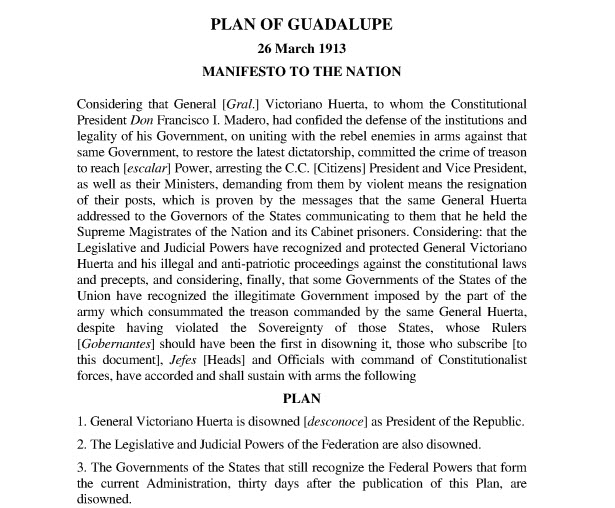

As promised, Huerta was awarded the presidency in February of 1913. In response to the coup, former anti-Díaz rebel Venustiano Carranza declared his intentions to oppose Huerta in his own political manifesto, the Plan of Guadalupe. Among its several points, the plan proposed the establishment of a constitutional government.

Meanwhile, newly elected U.S. President Woodrow Wilson refused to acknowledge Huerta’s government. Under his administration, the U.S. government actively supported Mexican revolutionaries. Watching his political power quickly decline, Huerta resigned in mid-1914 and willingly went into exile. Venustiano Carranza, Pancho Villa, and Emiliano Zapata—all leaders of separate revolutionary factions—met in one final attempt at peace, but could not reach an agreement. With no remaining political structure to rely on, Mexico found itself in the throes of a civil war.

Ultimately, the U.S. government found the Villa and Zapata factions too radical and placed its interests in Carranza and his Constitutionalist Army. With the United States’ help, the army pushed back the counter-revolutionaries and solidified Carranza as the next political leader of Mexico by April of 1915.

Over the next year, delegates met at the Constituent Congress to outline a new Mexican constitution that would consolidate many revolutionary principles into federal law. To appease villistas and zapatistas, delegates to the Congress included some of their more radical tenets, such as land reform. Meanwhile, under the guidance of Mexican feminist Hermila Galindo de Topete, Carranza sought to improve the legal status of Mexican women, workers, and peasants.

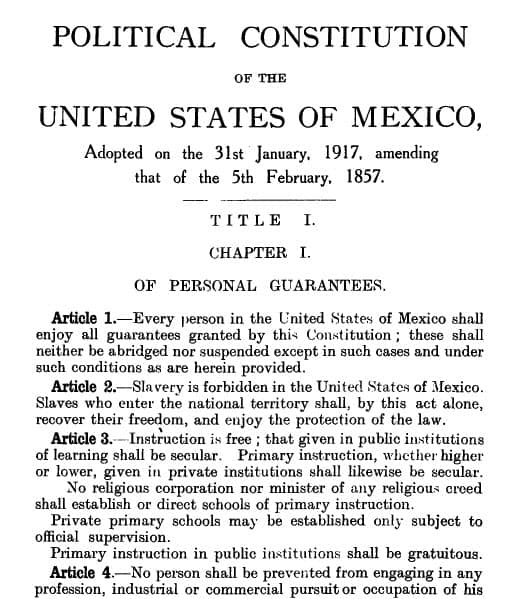

The result of the Constituent Congress was the Mexican Constitution of 1917, the first constitution in the world to incorporate social rights. Founded on principles such as human rights, separation of powers, and separation of Church and State, the constitution paved the way for land reform, empowered the working class, laid a foundation for free and secular education, and restricted the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico.

The Mexican Constitution has been amended hundreds of times since its ratification. Find the amending laws and multiple consolidated texts in World Constitutions Illustrated to see how the document has changed over the decades.

Love to Learn?

At HeinOnline, we love to research topics of all shapes and sizes. We share that love on our blog by using HeinOnline databases to research anything and everything under the sun.

Don’t miss out! Receive this quality content right to your inbox by subscribing today.