This month, HeinOnline continues its Secrets of the Serial Set series with an investigation of individuals with disabilities throughout American history.

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative monthly blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set.

The U.S. Congressional Serial Set is considered an essential publication for studying American history. Spanning more than two centuries with more than 17,000 bound volumes, the records in this series include House and Senate documents, House and Senate reports, and much more. The Serial Set began publication in 1817 with the 15th Congress, 1st session. U.S. congressional documents prior to 1817 are published as the American State Papers.

The Serial Set is an ongoing project in HeinOnline, with the goal of adding approximately four million pages each year until the archive is completed. View the current status of HeinOnline’s Serial Set project below.

These posts have been so informative; they enable both patrons and staff to understand what the Serial Set is and how invaluable it is to all kinds of research.

A Time of Confusion

People with limiting physical or mental conditions have long been the largest minority group in the world. Their history of persecution and isolation runs alongside all of human history—for as long as humans have existed, so has disability.

Fear of the “other,” the “abnormal,” or the “not-like-me”—sometimes seen as a natural human tendency—is often precipitated by a lack of knowledge or understanding, and can still be seen in race relations, gender discussions, foreign affairs, and other world issues today. For centuries in the Western world, this insufficient understanding led people to consider mental and physical disabilities to be punishments from God, or even the work of demons. This fear-induced perception led most to ostracize, isolate, or abandon those with what we would consider to be disabilities today. Those who weren’t hidden from view and forgotten became a source of entertainment, increasingly incorporated into circuses and freak shows.

Though less is known about disability in Colonial America than later periods, it appears that most people with disabilities became associated with poverty, criminal activity, and even disease. Those without families to care for them and without the ability to work became homeless, leading them to become the town’s responsibility. Towns typically sent these individuals to almshouses—county-funded institutions that provided food and shelter for the poor, sick, or criminal. Those who struggled to care for themselves thus became roommates with what society considered to be the lowest of the low. It wasn’t long before they became characterized as such, as well.

The earliest group of people with disabilities to receive some relief were those who suffered injuries in war efforts. One of the first disability laws was signed in 1776—a pension law for those significantly injured in the Revolutionary War. In 1798, U.S. President John Adams signed another military disability law, as well, providing relief for sick or disabled seamen.

The American Enlightenment

The intellectual growth and expansion in reasoned thought that had led to the American Revolution persisted beyond its success. The late 18th and 19th centuries saw what would come to be known as the American Enlightenment, an era where scientific reasoning was increasingly applied to all sorts of issues, including politics, religion, and in particular, human nature. The growth of the medical field and rise of more modern psychological thought helped bring about a greater understanding of all humans, and especially those who had been perceived as inferior, such as people with disabilities.

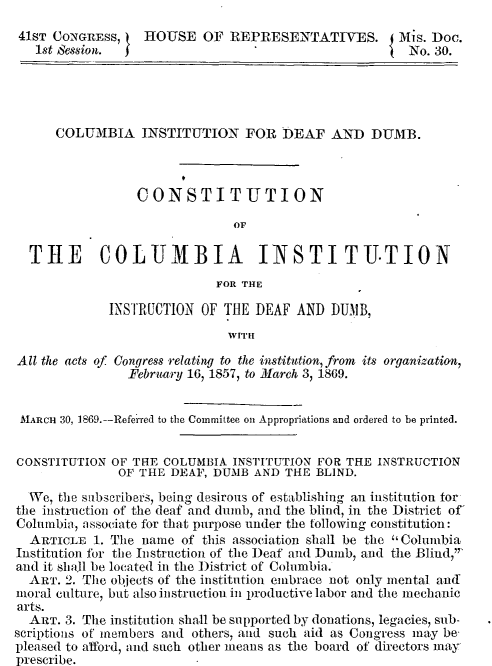

Instead of a religious or moral problem, people with cognitive or physical limitations now became a concern for medicine, psychology, and education. The rapid creation of larger cities and states allowed for local governments to take on responsibility of these populations. The solution was, at times, the placement of these individuals in institutions or schools intended to meet their needs, though the conditions in these establishments were usually horrific.

By the mid-1800s, this era of great scientific and economic progress had naturally begat critical thought, and therefore, social reform. Anti-slavery and women’s rights movements had risen to prominence, bringing about widespread change and the former even leading to civil war. Social reformers advocating for those with disabilities also made their voices heard, though other movements still took precedence. Activists such as Dorothea Dix decried the appalling conditions of jails, almshouses, and asylums across the United States, appealing to Congress that the United States set aside millions of acres of land to accommodate persons with disabilities. The request was passed by both houses of Congress, but ultimately vetoed by President Franklin Pierce.

In addition, a movement that threatened to undercut the work of disability activists appeared toward the end of the 19th century—social Darwinism. Stemming from Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, social Darwinists argued against state aid to the poor and disabled on the basis that it would undermine the “survival of the fittest.” From the late 1800s through the end of the next century, American cities would go so far as to enact “ugly” laws—laws prohibiting “any person, who is diseased, maimed, mutilated or deformed in any way, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object, to expose himself or herself to public view.” See an example from the 1895 laws of Nebraska relating to the City of Lincoln.

The Early 20th Century

The turn of the century brought dramatic change to the United States. Physically, the rural landscape was gradually transformed by a smattering of industrial cities. Socially, a rise in immigration led to increased fear, judgment, and frustration. Ways to quantify human worth appeared with the intelligence quotient (IQ) and similar tests, and the U.S. began to categorize people accordingly—notably in strict immigration policies and with segregation in education by color, sex, and special needs.

Perhaps out of the social Darwinism that preceded it, the eugenics movement surfaced, advocating for the improvement of the human race by better breeding. Individuals with cognitive disabilities who had been placed in institutions were often sterilized before their release, and in 1907, the first eugenics law was enacted in Indiana, promoting the sterilization of “confirmed idiots, imbeciles, and rapists.” The law spread to 24 other states within the next decades. In 1927, the Supreme Court ruled in Buck v. Bell that compulsory sterilization of mentally defective individuals was constitutional—a ruling that has yet to be expressly overturned.

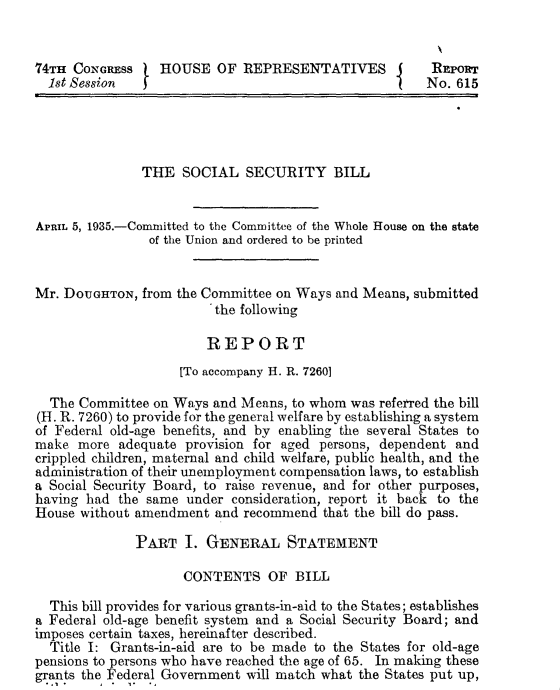

In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president, though he was afflicted with an illness that gave him permanent paralysis. With disabilities still stigmatized, he hid his vulnerabilities, but helped the cause of people with disabilities through the passage of the Social Security Act and its program of permanent assistance to disabled adults. Meanwhile, however, eugenics reached its extreme in Germany with the rise of the Nazi party. Classified as “life unworthy of life,” hundreds of thousands of people with cognitive and physical disabilities (along with homosexuals, the “insane,” and other “degenerates”) were sterilized against their will, while others were euthanized as part of a Nazi mass murder program.

The Era of Civil Rights

The end of World War II and its horrors sparked an awakening of sorts in the United States. Parents began to organize and demand services for their children with disabilities, and educators promoted the idea that people with these afflictions could be taught or rehabilitated. The rise of television brought images of all sorts of different people to American living rooms, and provided platforms for celebrities to speak about social issues, including the rights of individuals with disabilities.

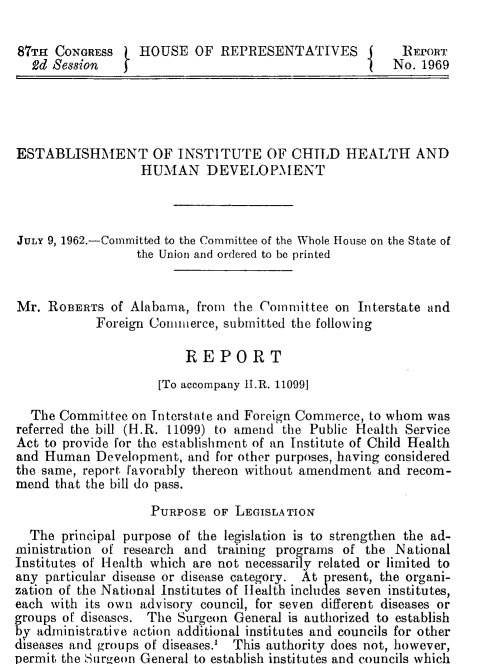

In the 1960s, an American president was elected who had his own personal connection to cognitive disability—John F. Kennedy. Following a failed prefontal lobotomy, Kennedy’s sister had been rendered incapacitated, her mental functioning reduced to that of a toddler. President Kennedy subsequently made intellectual disabilities a priority for his administration, establishing the President’s Panel on Mental Retardation and founding the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. In October of 1963, a month before his assassination, Kennedy signed the first major legislation to combat mental illness and intellectual disabilities—the Maternal and Child Health and Mental Retardation Planning Amendment to the Social Security Act.

With the influence of the Kennedy family and administration, public attitudes toward disabilities began to change, albeit slowly. The Civil Rights Act passed by President Johnson in the next year did little to address the needs of people with disabilities, precipitating the establishment of disability-focused organizations and protests throughout the ’70s. In response, the decade saw the creation of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons, as well as the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act. It was in this decade, as well, that the last of the “ugly laws” of a century earlier were finally repealed.

It wasn’t until 1990, however, that the first civil rights law specifically dedicated to people with disabilities was passed—the Americans with Disabilities Act. Signed by George H.W. Bush, the legislation afforded those with physical or cognitive limitations rights much like those given to other groups in the Civil Rights Act—prohibition of discrimination and equal opportunity and accommodations in employment, for example, but also the addition of accessibility requirements for public establishments. Considered central to the act’s passage were several disability rights activists who gathered in front of the Capitol Building, removed their crutches and wheelchairs, and slowly pulled their bodies up its front steps while calling for the recognition of their rights.

Since then, further legislation and decisions have been enacted to improve the experience of individuals with disabilities in this country, including providing people with disabilities the right to live in the community (rather than in institutions), offering direct aid to ensure individuals have the assistive technology they need, and providing all students with a disability the right to free appropriate public education tailored to their needs.

Help Us Complete the Project

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us, please contact Shannon Hein at 716-882-2600 or shein@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give special thanks to the following libraries for their generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

- Wayne State University

- University of Utah

- UC Hastings

- University of Montana

- Law Library of Louisiana

- George Washington University

- University of Delaware

We will continue to need help from the library community to complete this project. Download this Excel file to see what we’re still missing.