This month, HeinOnline continues its Secrets of the Serial Set series by exploring the Red Scares that dominated the first half of the twentieth century and forever impacted U.S. politics, defense, and foreign policy.

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative monthly blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Documents from additional HeinOnline databases have been incorporated to supplement research materials for non-U.S. related events discussed.

The U.S. Congressional Serial Set is considered an essential publication for studying American history. Spanning more than two centuries with more than 17,000 bound volumes, the records in this series include House and Senate documents, House and Senate reports, and much more. The Serial Set began publication in 1817 with the 15th Congress, 1st session. U.S. congressional documents prior to 1817 are published as the American State Papers.

The Serial Set is an ongoing project in HeinOnline, with the goal of adding approximately four million pages each year until the archive is completed. View the current status of HeinOnline’s Serial Set project below.

The First Red Scare

Communism Comes to Russia

By the 1900s, under Tsar Nicholas II, the Russian Empire had become one of the most impoverished European countries. A boom in industrial development had led to a large increase in the urban middle and working class, resulting in overcrowding, inadequate living conditions, and food shortages in major cities. Workers’ councils (known as “Soviets,” in Russian) soon sprang up across the country. A string of defeats in World War I only aggravated the situation, sparking riots that were in turn brutally suppressed by the tsar. Calls resounded for Nicholas II to transition from absolute to constitutional monarchy—a change that would limit his power to the bounds of an established legal framework.

The tsar resisted. Under the slogan “Peace, bread, and land,” a radical, far-left Marxist group known as the Bolsheviks surfaced, pushing for socialist revolution under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin. In February of 1917, hundreds of thousands of workers went on strike and filled the streets of Petrograd in protest. Instead of suppressing the riots, as ordered, the city’s troops mutinied and joined the protest. Nicholas was forced to abdicate the Russian throne for himself and his son.

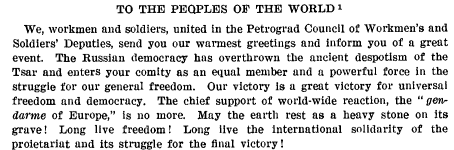

Peruse these letters between the U.S. Secretary of State and foreign ambassadors regarding the revolution and abdication and then view a statement from the Council of Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Deputies to the peoples of the world regarding their successful coup.

A provisional government was established to maintain essential services and continue fighting World War I. However, ravaged by internal conflict, the government was too weak to address the still-prevalent social, economic, and political crises. Only months after its establishment, the rule of the Provisional Government was upended when Red Guards—a military force consisting of former soldiers, factory workers, and peasants—infiltrated the Winter Palace.

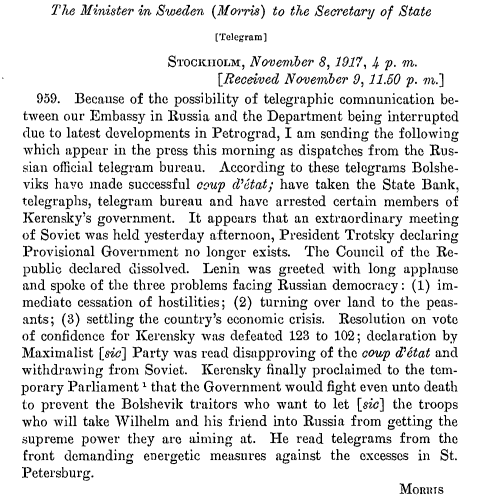

Civil war ensued between these “Reds”—so-named for their red flags—and “Whites”—a term borrowed from the French Revolution. Read these letters between the Secretary of State and foreign ambassadors regarding this second revolution.

This period, known as the “Red Terror,” became characterized by political repression and mass killings (including the execution in cold blood of the tsar and his entire family). The terror would continue until the Red Army’s total defeat of the Whites six years later.

In December of 1922, the Declaration and Treaty on the Formation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics officially created the Soviet Union (USSR). The USSR’s government was based on the one-party rule of the Bolsheviks, bringing communism to the level of state power for the first time in history. View the story of the Bolshevist movement from the United States’ perspective.

Fear in the United States

As revolution raged in Russia, the United States entered into the fray of World War I. Congress quickly passed the Espionage Act, which made it a crime to interfere with military operations or to support enemies of America. The addition of American men, equipment, and resources to the Allied front soon altered the trajectory of the war, and in November of 1918, Germany signed an armistice with the Allied powers.

World War I was over, and the world rejoiced—however, all was not well back at home in America. Just as Russia crumbled under the weight of a workers’ revolution, labor strikes increased on American soil. Spun by the press as communist propaganda, these strikes struck fear in the heart of Americans that life as they knew it could be dismantled, as it had been in Russia. In response, the Espionage Act was amended to forbid the use of “disloyal” or other “abusive” language about the U.S. government. (Many questioned whether this new legislation infringed on citizens’ First Amendment rights, but the act was deemed constitutional in a unanimous 1919 Supreme Court decision.)

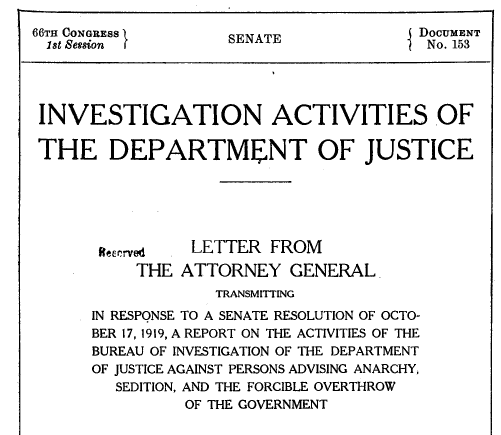

That same year, fear of the “Reds” increased when a series of bombs were simultaneously detonated by anarchists in eight major U.S. cities. At least 36 bombs were also mailed to a host of prominent Americans, including Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, J.P. Morgan, Jr., John D. Rockefeller, and Attorney General Mitchell Palmer. These acts of violence led Palmer to order a series of raids targeting suspected leftists, anarchists, and communists. All in all, more than 3,000 individuals were arrested and hundreds were deported, including several prominent leftist leaders.

Another World War

The Great Depression

The devastating impact of World War I left the world forever changed. The late 1920s and the 1930s witnessed the longest and most severe economic downturn the industrialized Western world had ever seen. What would become known as the Great Depression caused a substantial decline in employment, wealth, output, gross domestic product, and more across the globe.

Not helping matters any was the fact that four European powers had collapsed under the weight of the war. Bitterness lingered between nations—especially those forced to pay heavy reparations under the Treaty of Versailles. Damaged nations cultivated expansionist agendas all over the world, thus setting the stage for a second world war.

Nationalism on the Rise

By the 1930s, this economic distress and impending military conflict had made communism an attractive economic ideology for many—including some in the United States.

However, the events of World War I had left all nations with a strong sense of nationalism, and the United States was no exception. For example, in the early 1930s, the country designated a national anthem. Within the next decade, Congress would formally adopt the Pledge of Allegiance and, to investigate the extent to which Americans were disloyal or subversive (especially by having communist ties), establish a House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA).

Inspired by nationalist tendencies of its own, Germany invaded Poland under the direction of Adolf Hitler on September 1, 1939. Later, Germany, Italy, and Japan joined together to form the Axis powers due to their aligned expansionist interests. To combat the Axis powers, several nations formed the Allied powers, including France, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, the United States joined these Allies, as well.

Now embroiled in a second World War, the United States needed more sophisticated military and intelligence efforts. A month after the events at Pearl Harbor, Franklin D. Roosevelt formally authorized the Manhattan Project, a top-secret U.S. effort to weaponize nuclear energy (which had been discovered just four years earlier). Then, in 1942, Roosevelt further requested the establishment of a new organization which would collect and analyze strategic wartime information. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS), as it was named, became the primary wartime intelligence agency of the United States of America.

A Cold War Begins

Though they ended the Second World War as allies, the United States and Soviet Union could no longer ignore their ideological differences after the battles were over. The aftermath of the war had allowed the USSR to extend political and military influence over Eastern Europe, helmed by a fearsome dictator. Joseph Stalin and his Communist Party had, since Lenin’s death in 1924, ruled by terror, enacting rigorous censorship of art and science, creating an intricate spy network, establishing labor camps, and executing millions of uncooperative citizens. The Soviet Union’s post-war acts of expansion thus rightfully frightened those in the West.

However, following the devastation of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, both the United States and Soviet Union were hesitant to escalate hostilities. The two superpowers subsequently entered a “cold war” that would employ social, political, psychological, and economic tactics, rather than conventional warfare. The growing tension between the two raised concerns that communist and leftist sympathizers in the United States might actively work as Soviet spies—fears that were soon revealed to be legitimate.

The Second Red Scare

Espionage and Subversion Revealed

In 1947, the looming Cold War between the U.S. and USSR led to the creation of the Central Intelligence Agency. In the same year, to weed out communist influence in the U.S. federal government, President Harry S. Truman ordered the creation of a Federal Employees Loyalty Program, mandating that all federal employees be screened to determine their loyalty to the American government. Within less than ten years, more than five million individuals working for the federal government were investigated. An approximate 2,700 federal workers were dismissed, and 12,000 resigned. Read this overview of the program.

In Congress, investigations were also conducted into American communists, by both the House Un-American Activities Committee and the Senate, under Senator Joseph McCarthy. Users can find many of the proceedings against these individuals in the Serial Set—just use this summary index of all congressional investigations of communism and subversive activities between 1918 and 1956.

The investigations during the late 1940s, in particular, revealed the extraordinary breadth of a Soviet spy network that had infiltrated the federal government before, during, and after World War II, supported by the confessions of a number of U.S. government and citizen spies. Read more about decades of Soviet espionage here.

Anti-Communism Climaxes in America

In American eyes, fears of communism were starting to appear legitimate. The hysteria only became more ingrained in the U.S. government and society in 1949 when the Soviet Union created its first nuclear bomb and Communist Mao Zedong’s revolution successfully took over China. The expansion of communism around the world convinced many in the United States that there was a real danger of the “Reds” taking over their own country—a fan flamed fervently by Senator Joseph McCarthy.

McCarthy established himself as a feared and powerful figure in American politics, using smear tactics to fuel speculation of widespread communist subversion, even when he didn’t always have evidence to support his claims. In 1950, the senator made a speech in Wheeling, Virginia, for example, proclaiming that he was aware of 205 members of the Department of State that belonged to the Communist Party. Unable to ignore this claim and the massive media response that followed, the Senate asked McCarthy to present his case. On February 20, 1950, McCarthy cited 81 separate “loyalty risks” employed at the State Department.

The Senate voted unanimously to investigate, but ultimately did not find substantial evidence to support McCarthy’s accusations.

At around the same time, the Committee on Un-American Activities took an interest in investigating those in the entertainment industry. Drawing on a list of celebrities named in The Hollywood Reporter, the Committee subpoenaed a number of persons working in Hollywood to testify about infiltration of communist agents and sympathizers in U.S. film and media. Among those in the opening hearings were Walt Disney and Ronald Reagan, president of the Screen Actors Guild. Of 43 witnesses called, ten writers and directors refused to testify. The “Hollywood Ten” were subsequently cited for contempt of Congress, resulting in the first Hollywood “blacklist.”

Meanwhile, J. Edgar Hoover, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was also an ardent anti-communist. He had been a key player in the first Red Scares following World War I. Under his direction, the FBI used wiretaps, surveillance, and undercover operations in leftist groups to compile extensive evidence on suspected individuals. His work was essential to several high-profile cases, including that against Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, an American couple who were convicted of espionage and executed by the U.S. government in 1953.

The Korean War

Abroad, America focused its foreign policy on the “containment” of communism. After assuming the presidency in 1946, President Truman had pledged to “support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures”—a promise which has since become known as the Truman Doctrine. In 1950, this foreign policy extended to Asia, as the first major conflict was waged for the purpose of containment—the Korean War.

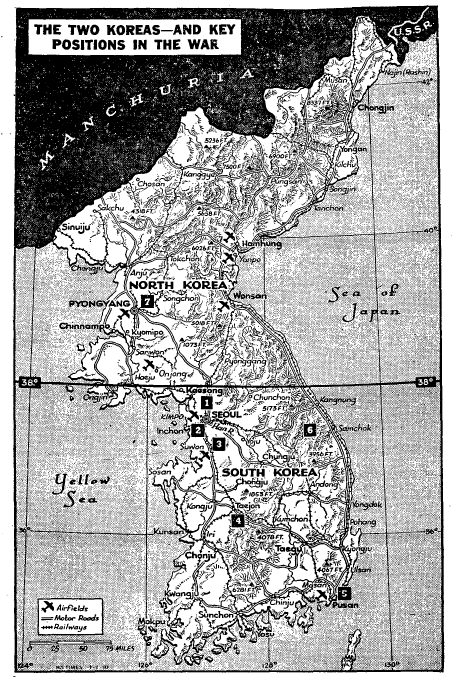

After the Second World War, Korea had become ideologically divided between a Soviet-supported communist government in the north and an American-supported government in the south. This ideological division turned physical when the United States and USSR agreed to temporarily divide Korea along the 38th parallel, bisecting the country.

However, on June 25, 1950, war broke out along the parallel when North Korean troops invaded South Korea and headed toward its capital, Seoul. Under the authority of a United Nations resolution, Truman quickly committed American forces to a combined military effort that included fifteen other nations. When explaining the decision, Truman stated, “Communism has passed beyond the use of subversion to conquer independent nations and will now use armed invasion and war.”

After a few years, a peace treaty ended the war and returned the country to a similarly divided status as before the conflict.

Communist Fears Dwindle

Back in the United States, anti-communism still reigned. However, in 1954, Senator McCarthy’s tactics were denounced by his colleagues, and he was formally censured by the Senate. With McCarthy’s downfall and an end to the Korean War came a simultaneous decline in excitement about a possible communist takeover.

Between 1955 and 1959, the Supreme Court decided several cases that restricted the way in which the government could enforce anti-communist policies. For example, in 1957, Yates v. United States (and later Scales v. United States, in 1961), the Court limited the ability of Congress to infringe upon the right to freedom of speech.

Though the Second Red Scare ended in 1957, the Cold War still persisted and remained predicated, at least in part, on the question of communism. Throughout the decades, the Soviet Union and United States continued to clash, first nearly coming to an all-out nuclear conflict during the Cuban Missile Crisis, then engaging in the Space Race, and then encountering each other again in the Vietnam War, a civil war between the communist North and pro-Western South. The Cold War continued on until 1991, when the Soviet Union dissolved into fifteen different states, including the Russian Federation.

Help Us Complete the Project

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us, please contact Shannon Hein at 716-882-2600 or shein@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give special thanks to the following libraries for their generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

- Wayne State University

- University of Utah

- UC Hastings

- University of Montana

- Law Library of Louisiana

- George Washington University

- University of Delaware

We will continue to need help from the library community to complete this project. Download this Excel file to see what we’re still missing.

Never miss a post!

Subscribe today to receive our Secrets of the Serial Set right to your inbox.