This month, HeinOnline continues its Secrets of the Serial Set series with a look back on the disastrous sinking of the RMS Titanic.

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative monthly blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Documents from additional HeinOnline databases have been incorporated to supplement research materials for non-U.S. related events discussed.

These posts have been so informative; they enable both patrons and staff to understand what the Serial Set is and how invaluable it is to all kinds of research.

The U.S. Congressional Serial Set is considered an essential publication for studying American history. Spanning more than two centuries with more than 17,000 bound volumes, the records in this series include House and Senate documents, House and Senate reports, and much more. The Serial Set began publication in 1817 with the 15th Congress, 1st session. U.S. congressional documents prior to 1817 are published as the American State Papers.

The Serial Set is an ongoing project in HeinOnline, with the goal of adding approximately four million pages each year until the archive is completed. View the current status of HeinOnline’s Serial Set project below.

Colonial Education

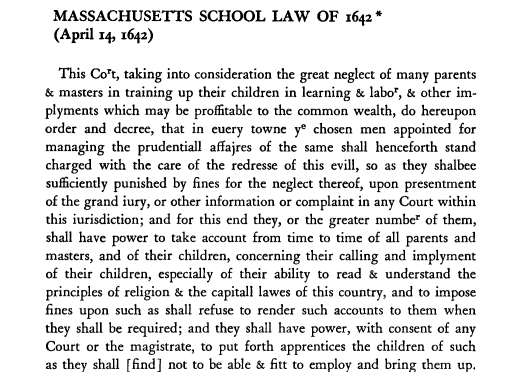

America’s education system finds its roots in the ideals of its original Thirteen Colonies. Early colonists (particularly the Puritans) valued the education of children as a way to improve literacy—which was necessary for religious study—and to foster the participation and growth of the colony’s community. Initially, responsibility for a child’s schooling rested in the hands of his family; however, by 1642, a law had been passed in the Massachusetts Bay Colony requiring that towns of a particular size establish a public school.

The Massachusetts “School Laws” (soon to be passed in other colonies, as well) made “proper” education compulsory. The cost of the schooling helped pay for the importation of English schoolbooks which, through a method of rote memorization, paired reading work with Bible verses that emphasized civic duty and morality. Colleges had a similar spiritual focus, with the majority of higher education geared toward the training of future ministers. Early institutions such as Harvard, the College of William & Mary, Yale, Princeton, and Brown were each closely associated with a specific branch of Christianity upon their founding. Until the mid-18th century, businessmen, government officials, lawyers, and doctors received their training through apprenticeship, rather than through colleges or universities.

Education Post-Revolution

By the 18th century, “common schools” had appeared (seen in early Indiana and Iowa statutes, for example), with students of all ages taught by one teacher in one room. In larger New England towns, these expanded into grammar schools (precursors to the modern high school), some of which still exist today. Still, some data shows that only 33% of children were receiving education in the 1770s.

In the years following the American Revolution, education became (and would remain) an increasingly important question for the budding democracy. The prevailing belief was that preservation of America’s experiment in self-government required a wise, virtuous, and informed population. Founding fathers such as Thomas Jefferson advocated early for the creation of a unified, public system of formal education, with Jefferson writing that “no other sure foundation can be devised for the preservation of freedom and happiness.” He even proposed a system of public schools for the Commonwealth of Virginia, organized by several square-mile school districts and free of charge for the first three years of a child’s instruction. By 1791, 14 American states had their own constitutions, and half of those states had specifically laid out provisions for education.

A Mann for All Seasons

By the 19th century, systems of education existed across the United States and, with the acquisition of new territories, large portions of new lands were set aside specifically for educational purposes. However, with education still a highly localized matter, the quality and content of schooling was quite inconsistent. Calls for a universal system of education continued, but acting on them was complicated by rapid expansion, an influx of immigration, and political tension during the early 19th century.

By the 1830s, one man had taken it upon himself to spearhead education reform in his state of Massachusetts. Upon appointment as Secretary of the recently established Massachusetts Board of Education, Horace Mann withdrew from all other activities and fully immersed himself in the problem of education. From traveling to schools, delivering lectures, holding conventions, and even observing school systems in other countries, Mann devised a system of education that grouped children by age, prescribed a curriculum for that age, introduced testing, and emphasized teacher training. By the end of the 19th century, this type of school—which some refer to as “factory model” today—had become widely popular in Massachusetts, and a variation of the system was soon established in many states thereafter. As an advocate for public education, historians credit Mann as one of the most important educational leaders of his time, and a major influence on our public education system today.

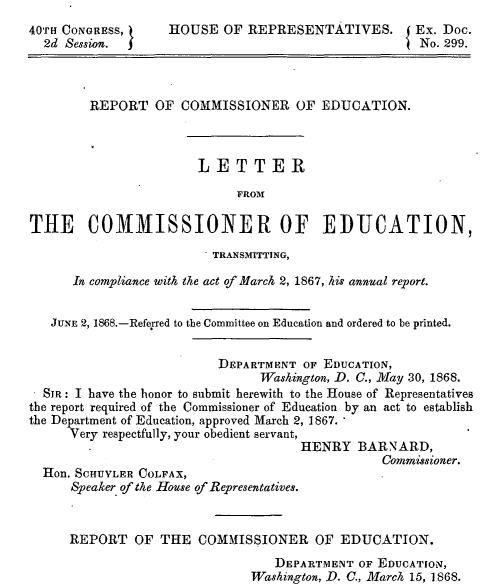

Following Mann’s death, the Department of Education was created during the Johnson administration to collect information and statistics about schools throughout the nation, and to assist states in their establishment of more effective school systems. Read the first report of the Commissioner of Education here.

Amidst fears that a cabinet-level Department of Education would have too much control over schools, however, the Department was demoted the following year to “Office” of Education, and this status would remain until 1979.

By 1870, every state in the Union had some system of free elementary education, and many states had passed laws to make schooling compulsory. Items found in the Serial Set reveal the research and comparison of educational systems performed by the U.S. government during this crucial time for American education. Take a look at some of these notable documents:

- Special report of the Commissioner of Education on the condition and improvement of public schools in D.C. (1868-1870)

- Annual Report of Commissioner of Education, 1871

- Education in Industrial Art and Fine Arts (1879-1880)

- Resolution on common-school education (1882)

- Industrial education in the United States (1882)

- Annual Report of Commissioner of Education, 1890

- Annual Report of Commissioner of Education, 1897

- Free kindergartens (1897)

Education and Early Science

The 19th century thus witnessed a rapid increase in the number of schools nationwide, as well as the number of attending students. By the early 1900s, the U.S. census shows that 72% of children attended school (an increase of nearly 20% since 1840). Alongside this increase came a surge in intellectual growth and expansion in reasoned thought that would come to be known as the American Enlightenment—an era where scientific reasoning was increasingly applied to all sorts of issues, including politics, religion, and, in particular, human nature and development. At the same time, the growth of the medical field and rise of more modern psychological thought helped bring about a greater understanding of all humans, and particularly children. As a result, research from world-renowned scientists and psychologists such as Ivan Pavlov, Jean Piaget, and Maria Montessori began to inform educational philosophy.

Then, in 1914, a complex web of political and military alliances dragged the majority of Europe into war. During World War I, the U.S. Army sought a way to better evaluate and delegate its recruits. The growing field of psychology came to the rescue, and the two industries came together to develop a series of mental tests. The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test, the first edition of a modern IQ (intelligence quotient) test, appeared in 1916. Within the next decade, the College Entrance Examination Board (headed by eugenicist Carl Brigham) devised the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), modeled off of the Army’s IQ exam. The SAT remains the standard for entrance into colleges and universities today (though, in recent years, institutions of higher learning have started to make these entrance exams optional). At the time of their creation, these tests were controversial in their reaffirmation of inherent contemporary biases toward different races, classes, and genders. The tests allowed for conscious and subconscious categorization in American society based on score, which contributed in part to strict immigration policies and segregation in education by color, sex, and special needs.

During this early period of standardized testing, educational theorist John Dewey analyzed and evaluated the purpose of education. He ultimately determined that, rather than simply being a method of imparting knowledge, schools should also act as a means for realizing the individual potential of each student. But, as elementary and secondary schools increased in number, so too did U.S. colleges and universities, leading to an increasing reliance on standardized testing. To prepare their students for entrance into higher education, schools began to adjust their curricula toward the goal of preparing students for college, rather than for life.

Addressing Inequality in Education

The worlds of politics and society changed after World War II, and therefore, so did the world of education. For example, with the emergence of the baby boomer generation, schools across the country saw unparalleled increases in population.

Despite this unprecedented school development, inequities between schools were rampant, and particularly so for the African American community. With the 1896 Supreme Court ruling under Plessy v. Ferguson, segregation of races in schools was considered constitutional, as long as the schools offered equivalent standards of education. Nevertheless, black schools suffered from inadequate resources, funding, and facilities when compared to their white counterparts. In 1954, however, the ruling was overturned under Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, with the new decision that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

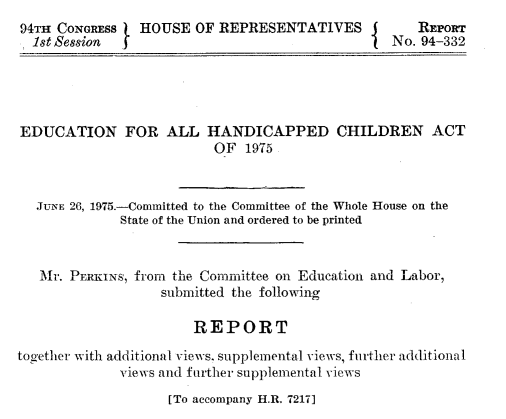

Individuals with disabilities then rose to the forefront of discussions about education in the 1970s. The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA) was passed by Congress in 1975, allowing for free, accessible education to all students with disabilities. In 1986, Congress amended the law to include children of a younger age. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1990 expanded upon definitions outlined in the EHA and revised its language from “handicap” to “disability.”

21st Century Education

In 2001, Congress reauthorized and updated the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965, which had previously provided federal funding for low-income students. This controversial reauthorization, known as the No Child Left Behind Act, initiated standards-based educational reform with the intention of closing the achievement gap. The act required that states measure the progress of their schools through standardized math and language exams, imposing penalties on those that did not demonstrate adequate yearly progress. Schools soon discovered, however, that their teachers were forced to “teach to the test” to meet the goals of the legislation. In addition, students with learning difficulties regularly fell short of the “proficiency” benchmark outlined by these standardized tests.

After reports in the early 2000s that American high school graduates did not possess the necessary skills and knowledge for employment and higher education, the National Governors Association (NGA) developed the Common Core State Standards Initiative in 2009. The standards reflected the mathematical and linguistic knowledge that students should possess to succeed in college and their future careers. As part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the Department of Education funded the Race to the Top Initiative, providing an incentive for states to adopt the Common Core Standards in order to advance education reform in K-12 schools.

In 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) replaced No Child Left Behind as a reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. The first bill in decades to narrow the federal government’s role in education, ESSA explicitly prohibited the Department of Education from incentivizing or coercing states to adopt the Common Core and other standards; however, it did not eliminate the provisions relating to periodic standardized testing. While 46 states initially adopted the Common Core Standards, 16 of those states have produced legislation to repeal the curriculum as of 2021.

As of 2005, more than 85% of adult Americans had completed high school, while 27% had received at least a bachelor’s degree. In 2014, the country marked a record high of graduating high school seniors, though some question whether this achievement can be attributed to declining academic standards. According to the Department of Education in 2003, Americans over 15 have a reading literacy rate of 99%, but rank below other developed countries in understanding of math and sciences.

This past year, the COVID-19 pandemic changed schools around the country when it required a shift to remote learning. The effect of this transition on the field of education and, more importantly, on the development of these children and adolescents remains to be seen. Regardless, this period is sure to be reflected on as a landmark moment in educational theory and practice.

Help Us Complete the Project

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us, please contact Shannon Hein at 716-882-2600 or shein@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give special thanks to the following libraries for their generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

- Wayne State University

- University of Utah

- UC Hastings

- University of Montana

- Law Library of Louisiana

- George Washington University

- University of Delaware

We will continue to need help from the library community to complete this project. Download this Excel file to see what we’re still missing.