This month, HeinOnline continues its Secrets of the Serial Set series with an exploration of the history behind Yellowstone National Park.

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative monthly blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Documents from additional HeinOnline databases have been incorporated to supplement research materials for non-U.S. related events discussed.

These posts have been so informative; they enable both patrons and staff to understand what the Serial Set is and how invaluable it is to all kinds of research.

The U.S. Congressional Serial Set is considered an essential publication for studying American history. Spanning more than two centuries with more than 17,000 bound volumes, the records in this series include House and Senate documents, House and Senate reports, and much more. The Serial Set began publication in 1817 with the 15th Congress, 1st session. U.S. congressional documents prior to 1817 are published as the American State Papers.

The Serial Set is an ongoing project in HeinOnline, with the goal of adding approximately four million pages each year until the archive is completed. View the current status of HeinOnline’s Serial Set project below.

Early History

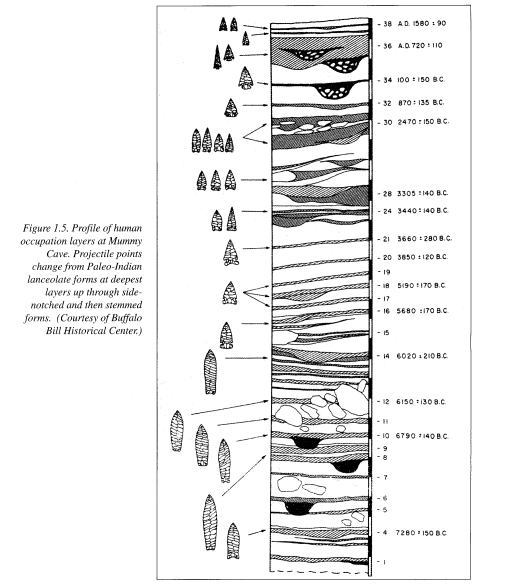

Yellowstone National Park is an almost-mythical region straddling the states of Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho. According to its brochure, it seeks to provide “a glimpse” of the American landscape before humans. In reality, however, humans have inhabited the Yellowstone region for at least 11,000 years.

Yellowstone is known to many around the world for its wildlife and geothermal facets, especially Old Faithful geyser. But the lands that make up the park are perhaps lesser-known as a popular hunting and gathering ground for early inhabitants of North America. Many early tribes were drawn to the area’s glacier-carved valleys, hot springs, black obsidian mountain, and of course, its abundance of game and fish.

Artifacts found throughout recent American history—obsidian arrowheads, for example—tell a story of indigenous American life in Yellowstone thousands of years before the arrival of American explorers.

Anglo Arrival

The Lewis and Clark Expedition

After acquiring the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 (a total of 530 million acres of land in the West), President Thomas Jefferson proposed to Congress that they launch an expedition to explore the widespread region. With a $2,500 grant, Jefferson was able to commission a group of army volunteers for this purpose, led by Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lieutenant William Clark.

As the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through present-day Montana on its two-year trek, its members encountered several indigenous tribes, including the Nez Perce, Crow, and Shoshone. They heard tell of a region to the south named by these tribes for its yellow rocks, but the expedition members chose not to investigate it.

Colter’s Hell

That is, all but one. One of the group, John Colter (later a famed “mountain man”) left Lewis and Clark’s party to join a group of fur trappers. In 1807, he would become the first known European to pass through the region which would later become Yellowstone Park. Upon his return home, he shared with anyone who would listen what he had found—a plateau of “fire and brimstone,” dotted with gurgling mud pots and steaming geysers.

Rather than inspiring fascination, Colter’s experience was laughed off as just another tall tale. The Yellowstone region, now jokingly known to some in the east as “Colter’s Hell,” would still only see a few trappers and hunters over the next few decades. The little-explored lands and their mysterious features would remain only a myth for years to come.

Formal Expeditions to the Region

It was not until after the American Civil War that formal expeditions would be launched specifically for the purpose of exploring the Yellowstone area. One of the first was headed by the surveyor-general of Montana, Henry Washburn, and one Nathaniel P. Langford, notable because he would later become the park’s first superintendent.

One member of this expedition, Cornelius Hedges, wrote in-depth articles about his observations of Yellowstone in the early 1870s. Astounded by what he saw, he was one of the first to propose that the region be protected and designated as a national park.

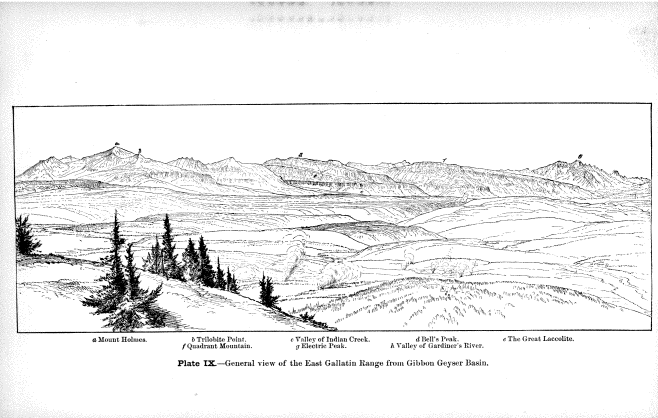

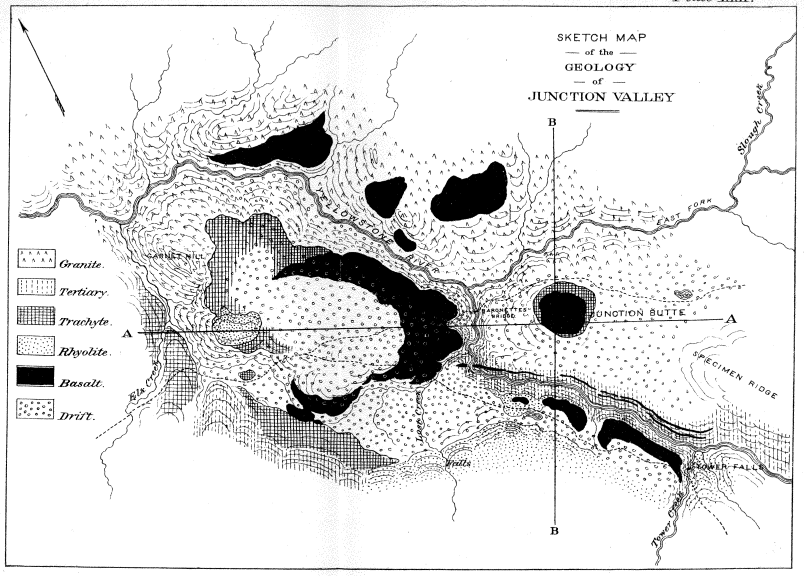

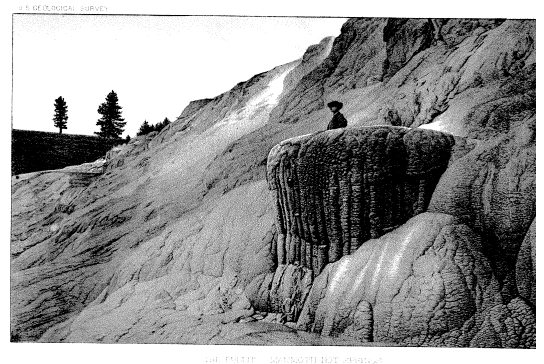

In 1871, another expedition was launched—this time sponsored by the U.S. government. Government geologist Ferdinand Hayden led the group, bringing with him photographer William Henry Jackson and landscape artist Thomas Moran. Hayden’s comprehensive report provided the first real proof to the U.S. government of Yellowstone’s majesty, while Jackson and Moran’s brilliant landscape images served to provide the first visual record of the region. Read Professor Hayden’s early reports on the territories of Wyoming and Montana.

See some of these maps, photographs, and illustrations of Yellowstone in this 1878 report from Hayden.

After his visit, Professor Hayden became passionate about Yellowstone’s fate, joining Hedges and others in persuading the government to set the land aside for protection. To allow others to easily see the region for themselves, he lobbied for Congress to fund the creation of a wagon route to the park, on which work began in 1873.

The First National Park

Congress Gets Interested

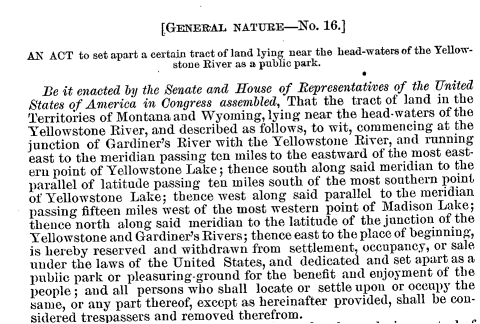

Following Hayden’s work, Congress moved to withdraw nearly 2 million acres of land in the Yellowstone region with the purpose of creating America’s first national park. The Yellowstone Act of 1872, signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant, made it official; the legislation designated Yellowstone as a public “pleasuring-ground” that must be preserved. The indigenous tribes that had inhabited the area were, of course, forced out—some ceding their lands in treaty with the United States with the promise that they could continue to hunt there.

For more information, read this historical and descriptive sketch of Yellowstone National Park prepared in the early 1900s.

The American Conservation Movement

The move—a surprising one for a nation driven by “manifest destiny”—would set a precedent for the preservation (rather than exploitation) of the American West. Environmentalists around the country would lobby over the next few decades for further wilderness protections; at the same time, early American artists would draw inspiration from the American landscape and 19th century writers (Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman, for example) would emphasize an appreciation and understanding of nature.

Amidst this conservation movement, Congress went on to establish dozens of other national parks, including Sequoia, Kings Canyon, and Yosemite.

Then, in 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act; under it, the executive branch received the authority to create national monuments, preserving areas of natural or historic notoriety as it saw fit. Roosevelt used the act to declare the first national monument, Devil’s Tower—an incredible 1,200+ foot-high granite formation in Wyoming.

Trials and Tribulations

Park Mismanagement

Though an exciting turning point for the United States, the country’s newfound interest in preservation was not without its difficulties. At first, each of these national parks and monuments were managed independently, which was at times unsuccessful. In Yellowstone, for instance, the park’s first superintendent, Nathaniel Langford, earned no salary, received no funding, and was given hardly any staff or resources to protect the lands. As the park became an increasingly popular tourist attraction, the poaching of buffalo, deer, antelope, and elk became just one of many issues. Read Langford’s first report on the newly established Yellowstone National Park here.

Encounters with Indigenous Peoples

Also during the late 19th century, those managing the Yellowstone area had to contend with the indigenous tribes that had been previously excluded from the area. About a half-dozen tribes that had regularly used the lands for hunting and gathering had been forced out at the time of the park’s creation. One of these tribes, the Shoshone, had left under the promise that they would still be allowed to hunt on the land. However, the United States never ratified the treaty, and therefore never recognized the tribe’s claims.

After unauthorized re-entry and some hostility from groups like the Nez Perce and Bannock peoples, the U.S. Army took control of Yellowstone Park in 1886, building Camp Sheridan there and establishing permanent fort structures over the next two decades. Read this report on Yellowstone Park from 1886.

The National Park Service

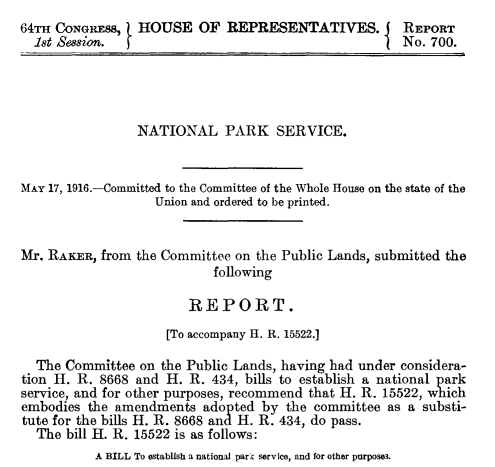

By the 1900s, something had to be done about the rampant poaching, indigenous entry, and other issues plaguing Yellowstone and other U.S. parks. Advocates for preservation petitioned the government to better protect national parkland on a federal level.

In response, President Woodrow Wilson created the National Park Service in 1916; the new agency, under the U.S. Department of the Interior, placed management of all of America’s national parks under one entity. Today, the Service’s mission remains the same—”to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein” and “leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Help Us Complete the Project

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us, please contact Shannon Hein at 716-882-2600 or shein@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give special thanks to the following libraries for their generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

- Wayne State University

- University of Utah

- UC Hastings

- University of Montana

- Law Library of Louisiana

- George Washington University

- University of Delaware

We will continue to need help from the library community to complete this project. Download this Excel file to see what we’re still missing.