One of the best features on HeinOnline – and one of the most useful for researchers and educators – is our extensive use of image-based, fully-searchable PDFs of historical documents. In this month’s edition of HeinOnline in the Classroom we’re going to focus on a particular historical document from HeinOnline’s collection: Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham City Jail.“ Keep reading for more about this monumental work, and for two activities that you can use in your classroom to help your students engage with “Letter from Birmingham City Jail.”

Background: The Birmingham Campaign

King wrote the letter while imprisoned, as the title suggests, in a jail in Birmingham, Alabama, following his arrest during the campaign to desegregate businesses in the city. The Birmingham Campaign began on April 3, 1963, when King and civil rights activists from around the country joined with local activists in Birmingham in a series of direct actions – including marches, boycotts, and sit-ins – aimed at pressuring local businesses to desegregate their facilities. The protests were so successful in pressuring the local business community that, on April 10, the government of the city of Birmingham obtained an order from a segregationist court[1]The order is referenced in Walker et al. v. City of Birmingham, 388 U.S. 307, 349 (1967). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. to declare the protests illegal. When the protests continued, King and many others were arrested on April 12.

It was on this same day that eight local clergymen published an open letter,[2]Letter from Birmingham City Jail (1963). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Civil Rights and Social Justice database. condemning King and his fellow activists as “outsiders” whose actions served to “incite hatred and violence,” while defending the heavy-handed and brutal police response to the nonviolent direct action anti-segregation campaign. It was in response to this letter that King wrote his response to the eight Alabama clergymen, from his solitary confinement cell, initially writing his draft on scraps of newspaper that were smuggled out of the city jail.

King’s Letter

Today, King’s letter is recognized as one of history’s most incisive commentaries on the use of direct action as a tactic of resistance against societal oppression, and an impassioned defense of civil disobedience in the face of unjust laws. It is widely taught in writing classrooms, not only as an important historical work, but as an exemplar of intellectually and stylistically skillful argumentation. In King’s time, the letter circulated rapidly for these same reasons.

“Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust…So I can urge men to obey the 1954 decision of the Supreme Court because it is morally right, and I can urge them to disobey segregation ordinances because they are morally wrong…An unjust law is a code that a majority inflicts on a minority that is not binding on itself. This is a difference made legal. On the other hand a just law is a code that a majority compels a minority to follow that it is willing to follow itself. This is a sameness made legal.” [3]Letter from Birmingham City Jail (1963). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Civil Rights and Social Justice database.

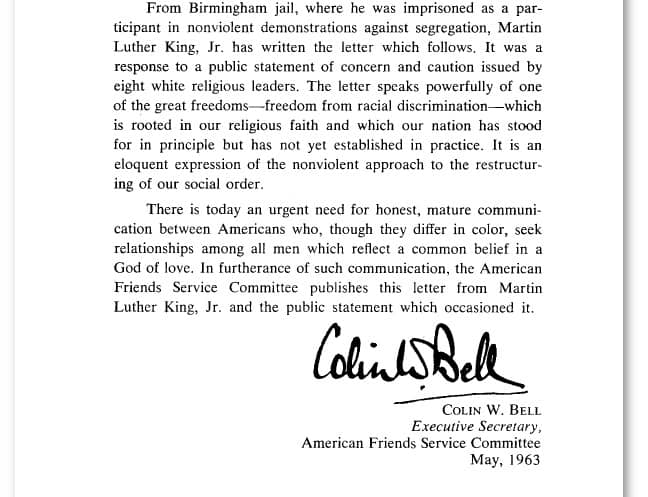

The first complete edition of King’s letter was published in 1963 as a pamphlet by the American Friends Service Committee, the activist arm of the Society of Friends (commonly known as the Quakers). The AFSC printed and distributed thousands of copies of the pamphlet in the lead-up to the March on Washington later that summer. The letter reached further audiences when it was later republished, under a different title, in The Atlantic. A scanned first-edition of King’s letter, as published in the AFSC pamphlet, is available on HeinOnline, as part of our perpetually free-to-access Civil Rights and Social Justice database (Access Database | View LibGuide).

The great thing about image-based PDFs is that they present historical documents, such as King’s letter, in the context in which they were originally published and read. For instance, the edition of “Letter from Birmingham City Jail” on HeinOnline is scanned from a copy of the first edition borrowed from the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library. It includes materials that are not always available in other printings of the work, such as the introduction from the AFSC, and a reprint of the letter from the eight Alabama clergymen to whom King was responding.

Below are two activities that you can use in your classroom to bring this important work to life for your students. The first activity consists of some guided discussion questions, which you can have students work on individually or in small groups. I think questions number two and three are particularly useful, because they address one of the most common pitfalls for students when confronted with historical texts: esoteric references and historical allusions. In my experience, when they are confronted with references to unfamiliar people, places, and things in historical texts, many beginning students will simply skip over them. If we get our students in the habit of looking up unfamiliar references early on in the semester, it will benefit them immensely later on in the semester when they are working on more independent research.

Activity #1: Guided Discussion Questions

Break students up into small groups to talk over these questions in class.

- How does King define an unjust law? What do you think of this definition? Would you add anything to or change anything about his definition?

- King makes numerous allusions and references to philosophers, religious figures, and situations. Look up some of the people, stories, and situations he references. Why does he choose to refer to them? How do they help his argument?

- As a group, make a list of other people, stories, and situations that King references with which you are not familiar. Look them up. What is their significance? Why do you think King chose to refer to them?

- Beyond the eight clergy members to whom the letter is addressed, who do you think King’s intended audience is? What makes you think this? Where in the text do you see him addressing this audience or audiences?

- As a group, come up with at least one additional question/prompt that you would like the class to discuss.

Activity #2: King’s Use of Rhetorical Appeals

This is another good in-class activity that, in addition to helping students understand the role of rhetoric in crafting arguments, you can also use to help students develop and practice their public speaking and presentation skills in a relatively low-stakes classroom environment.

Divide your students up into small groups, and assign each one a portion of King’s letter to analyze and discuss. In this instance, I broke the students up into only three groups, but you may want to adjust the number of groups if you have a larger class size. For this activity, you’ll be having your students focus on King’s argumentative techniques at the paragraph and sentence-level, so it is helpful break the text up by paragraphs.

- Group 1: Paragraphs 1-9

- Group 2: Paragraphs 10-17

- Group 3: Paragraphs 18-28

In the first-year writing classroom, this activity works great as a follow up to a lesson or unit on classical rhetoric and argumentation, as it prompts them to apply concepts from the study of rhetoric to a real-world situation.

For each of their assigned paragraphs, have students analyze and summarize the argumentative strategies King is employing. What claim(s) is he making in each paragraph? What rhetorical appeals does he employ as he supports his claim(s)? (For reference, the Purdue OWL has a good description of Aristotle’s model of rhetoric here).

After your students have had an opportunity to discuss and analyze King’s arguments in their groups, have each group deliver a mini presentation to the whole class where they describe their findings. If you want to go all-out, you can carry this over into the next day of class and have students prepare multimedia group presentations. I usually have students deliver individual presentations of their research toward the end of the semester, and I have found that giving them an opportunity to present in a more low-stakes environment as part of a group prior to that is helpful.

Classroom Tip of the Month

Something I wish that I had considered earlier in my teaching career is the importance of accessibility when crafting my syllabi and assignment sheets. A syllabus is the first introduction students have to our classes, with students often accessing them prior to the first course meeting and basing their decisions on enrollment upon them. One of the most important things to consider with a syllabus is that it is accessible to all students. There are a number of ways that we can improve the accessibility of our course documents, for students with disabilities in particular. One relatively easy thing I started doing is using preset Heading styles in Microsoft Word and Google Docs — these increase the ease of navigation for all students, and are particularly useful for blind students who might use reading technology to access course documents. For more information on ways to make your course syllabus more accessible, check out the Accessible Syllabus Project.

Have a great rest-of-November, and good luck with the home stretch of the semester!

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | The order is referenced in Walker et al. v. City of Birmingham, 388 U.S. 307, 349 (1967). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Letter from Birmingham City Jail (1963). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Civil Rights and Social Justice database. |

| ↑3 | Letter from Birmingham City Jail (1963). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Civil Rights and Social Justice database. |