Most would agree that the future of the human race depends on the capability of its offspring. At the turn of the 20th century, with the rise of the eugenics movement, this premise was taken to a logical yet dismal conclusion: the human race could be improved if only the genetically superior were allowed to reproduce.

Though such talk may be repulsive to many in the modern era, it was surprisingly commonplace just a few generations ago. Even more shocking, you’ll find notable, well-respected names on the list of advocates for the practice. It was only when eugenics was taken to its extreme under Nazi Germany that the movement began to fall out of favor. Keep reading to explore the rise and fall of the eugenics movement with HeinOnline.

A Brief History of Eugenics

A Dangerous Idea

Though the term “eugenics” was coined at the end of the 19th century, eugenic practices have existed in societies around the world for thousands of years. Think back to your middle school history class and you might remember that in the ancient military state of Sparta, weak or deformed newborns were killed, thrown off of the top of Mount Taygetos. Ancient Greek philosopher Plato famously proposed a state-monitored human mating and reproduction program to produce a “guardian” (or ruling) class. According to the Twelve Tables of Roman Law, deformed or otherwise “monstrous” children born into Roman society were required to be put to death.

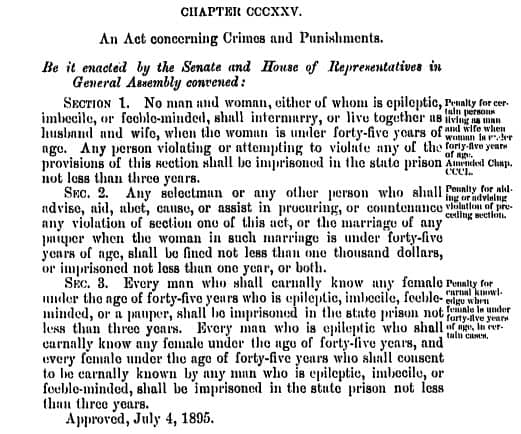

Several centuries later, scientist Charles Darwin proposed the theory of evolution in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species. Later, Francis Galton, Darwin’s half-cousin, became fascinated with his concept of “natural selection”: the process by which organisms adapt to their environment by selectively reproducing changes in their genotypes. Galton theorized that human characteristics (intelligence, for example) were heritable traits and that society, with its tendency to protect the weak, was preventing natural selection in humans. In 1883, Galton coined the term “eugenics”—literally meaning ‘good birth’—and within the next few decades, the theory took off with academics and policymakers alike, particularly in the United States. It’s no surprise then that in 1895, Connecticut became the first state to enact a marriage law featuring eugenic criteria—it prohibited marriage on threat of imprisonment for anyone who was “epileptic, imbecile or feeble-minded.”

Fun Fact: Francis Galton was a polymath who dipped his hands into several subjects. He is responsible for identifying patterns in fingerprints and devising the fingerprint classification system used in forensic work today. Read Galton’s book on fingerprints here.

The Movement Takes Hold in America

In the 1900s, the U.S. eugenics movement evolved to focus on eliminating negative heritable traits, rather than only selectively breeding for positive ones. Eugenicists began to notice the greater proportion of deaf children born to deaf parents compared to the number born to hearing ones, and in the same vein, the sizable birth rates among immigrants whose heritage was “proven” to be correlated with undesirable heritable traits. It soon became clear that to eliminate negative traits, “undesirables” couldn’t be allowed to reproduce.

In 1903, the American Breeders Association was founded to study the laws of breeding, with membership including the likes of inventor Alexander Graham Bell and first Stanford president David Starr Jordan. In 1911, John H. Kellogg (famous for the cereal) established the Race Betterment Foundation, and biologist Charles Davenport, funded by the Carnegie Institution and Harriman railroads, created the Eugenics Record Office (ERO).

Field workers for these organizations soon began tracking families, using the data to establish pedigrees which outlined the inheritance of undesirable traits throughout generations. Meanwhile, eugenic principles made their way into the culture of the day, with families excitedly taking part in “Better Babies” contests and “Fitter Families” competitions, akin to the judgment of livestock that one might see at a county fair. Many feminist advocates took on the eugenics cause, including Margaret Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood and one of the most well-known early advocates of birth control.

Eugenics in U.S. Legislation

In 1907, Indiana became the first state to pass a compulsory sterilization law for “criminals, idiots, imbeciles and rapists.” Other states followed suit until at one point, 33 states permitted involuntary sterilization of those deemed undesirable for procreation. In 1927, when the constitutionality of these laws were called into question, the Supreme Court upheld state compulsory sterilization laws—a ruling that has yet to be expressly overturned. As a result, between 1907 and 1963, more than 64,000 people were involuntarily sterilized under U.S. eugenic legislation.

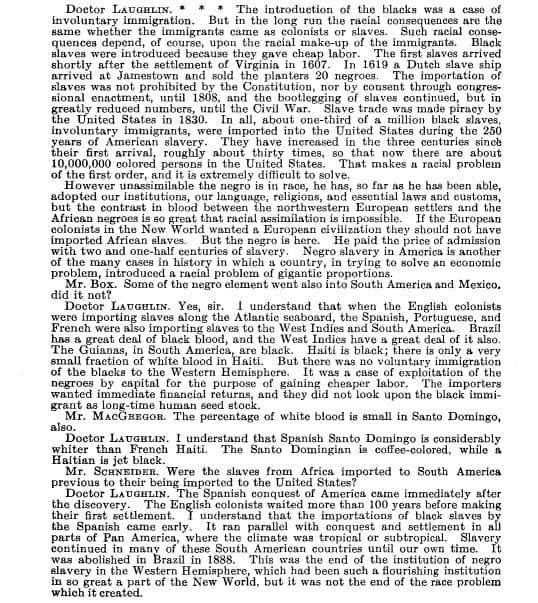

Around this time, eugenicists also lobbied for stricter federal laws, particularly regarding immigration. In the early 1920s, eugenicist Harry Laughlin served as expert advisor to the House Committee on Immigration, warning Congress of the entrance of “inferior stock” into American society. The Immigration Act of 1924 was one result of this work, effectively banning all immigration from Asian countries. Later, some policymakers felt that a fault of the act was that it did not extend to countries in the Western Hemisphere, allowing undesirable immigrants from Mexico, Central, and South America. As part of that debate, Laughlin’s work was brought in once again. See his comments about the problem of African American descendants below.

Laughlin was later compelled by the Special Committee on Immigration and Naturalization to restudy the problem. Read his research here.

The Nazis Take Things Too Far

In the 1930s, the eugenics movement became popular enough to reach the scientific community in Germany. U.S. eugenicists encouraged the promotion of their philosophy overseas, and the Rockefeller Foundation assisted in the development of various German eugenics programs.

When Adolf Hitler rose to power in the 1930s, he did so with prior knowledge of eugenics and a belief that the German people had become weak because defective genes were running rampant throughout the population. Hitler’s regime used eugenic propaganda to promote the “Aryan” race as the most pure, and introduced policies in pursuit of racial hygiene.

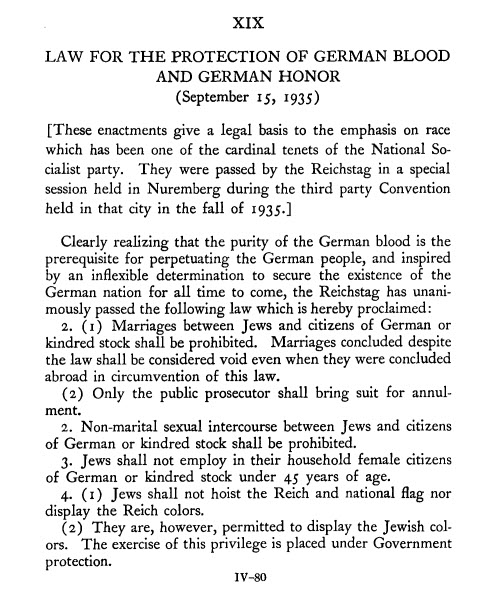

1935 saw the first Nazi policies regarding racial superiority with the Nuremberg Laws, which prohibited marriages and sexual relations between Germans and people of Jewish ancestry.

Later, it was required that German marriage partners be tested for hereditary diseases, and contraception and abortion were restricted for couples.

Modeling off of state laws in America, Germany began its own forced sterilization programs—they were specifically inspired by work being done in California, which by 1933 had forced more sterilizations than every other state combined. By the mid-1930s, more than 5,000 people a month were undergoing compulsory sterilization in Germany. Then, in 1936, the connection between German and American eugenics became abundantly clear; Harry Laughlin was invited to Germany to receive an honorary doctorate for his contributions to the “science of racial cleansing.”

German eugenics, inspired by the American movement, became the foundation for increasingly oppressive Nazi policies, the Hitler regime’s establishment of concentration camps, and its ultimate genocide of millions.

Eugenics in the Modern Era

The end of World War II and revelation about the horrors of Nazi Germany sparked an awakening of sorts around the world, and particularly in the United States. A series of thirteen trials were held, bringing to justice those responsible for the heinous crimes committed during the war. Afterward, the eugenics movement as it existed in the States declined, nearly entirely discredited by the work of the German Reich.

However, the core concept of eugenics—increasing desirable heritable characteristics through human reproduction—is far from gone. You could say that, instead, it has evolved, distancing itself from the negative connotations associated with the term by taking on the name “genetic engineering.” As medicine and technology have advanced, so has our ability to alter or eliminate genes, improving the human body by preventing or curing diseases, for example. This modern eugenics has led to the development of life-saving medical interventions, including recombinant insulin—the first genetically-engineered drug.

Do the benefits of modern eugenics outweigh the field’s frightening past? How far should genetic engineering go? How does one objectively determine a human trait as “undesirable?” The ethics of these questions cannot be ignored as we foray into this exciting and terrifying scientific frontier. Regardless of your stance on this controversial topic, one thing is certain—the history of eugenics and its clear political ramifications should be a cautionary tale for pioneers moving forward.

Scholarly Work on Eugenics

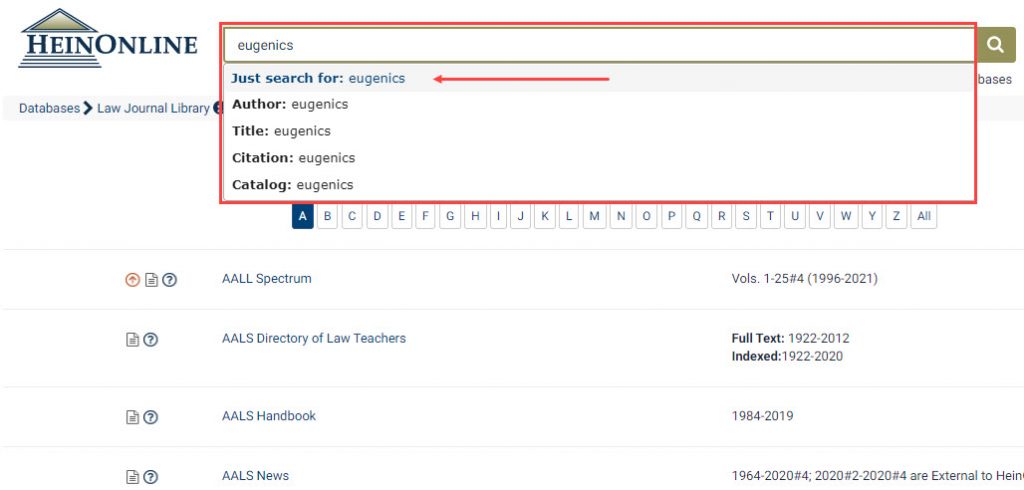

Let’s research this topic in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library to see what scholarly work is available. Using the Just search for option on the Law Journal Library landing page, enter the phrase eugenics and click the search button. Right away, we’re greeted with several interesting related articles:

- Rational Eugenics

- Problems in Eugenics

- Genius and Eugenics

- Eugenics and Feeblemindedness

- Eugenics and Legislation

- Eugenics and the Social Good

- Positive Eugenics and the Law

- Genetics, Eugenics, and Public Policy

- Eugenics: Old Ideas, New Tools

- Reproduction with Technology: The New Eugenics

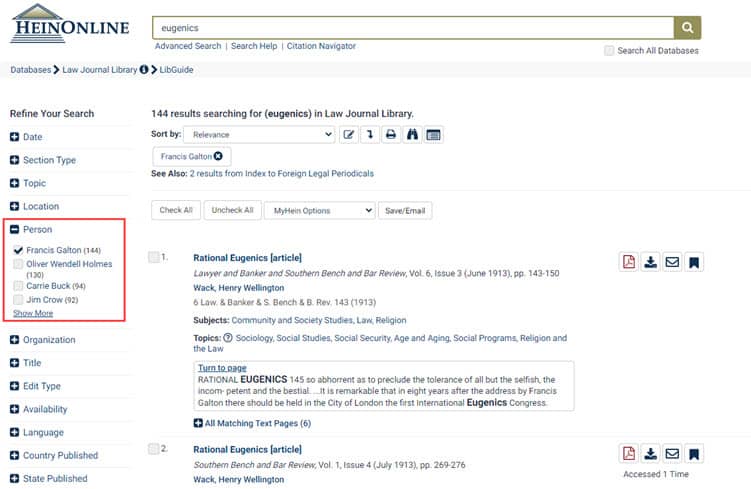

Our search was very broad (giving us 8,300 results), but we can refine it using the facets on the left-hand side of the results page. We can filter by date, section type, topic, location, person, organization, title, edit type, language, country published, and state published.

Topic, Location, Person, and Organization are all facets that use data extracted by HeinOnline’s machine learning algorithm. Person, for example, lists out individuals that are mentioned frequently throughout the works in our results and are important to the field of study being researched. We can see that this is the case here right away when we open the Person facet—our friend Francis Galton (who coined the term “eugenics”) is at the top of the list.

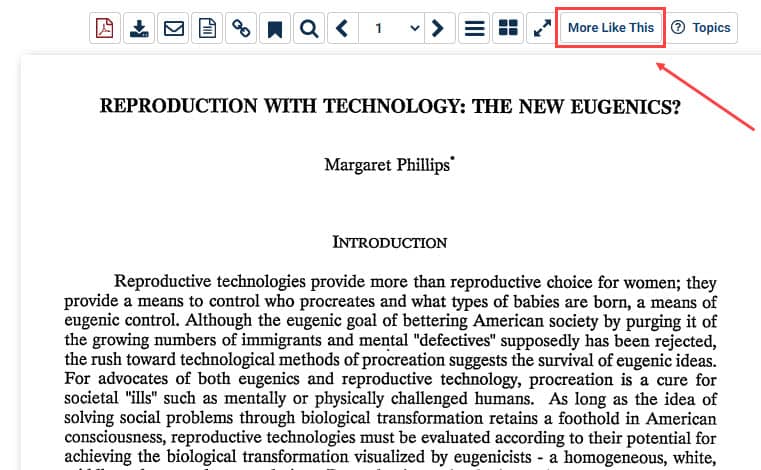

We can take advantage of HeinOnline’s machine learning even further to make even this simple starting search do the work for us. Click on any article that sounds interesting to you—we’ll go with Reproduction with Technology: The New Eugenics. From here, you’re able to utilize the More Like This button to find articles that are similar to it based on their frequent mentions of the same words or topics.

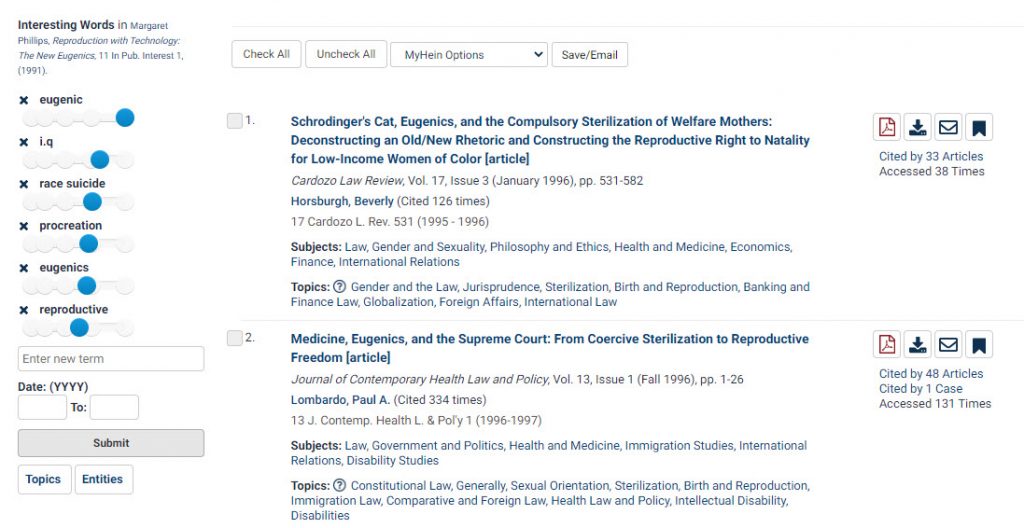

Here are the More Like This results for the article we chose:

You can see the extracted words that are generating these similar results on the left-hand side. Adjust the weight of these words as necessary using the blue slider, or remove them entirely from your search if you feel they’re not applicable. Enter a new term if you wish, or filter by a specific date range.

Stay in the Know with HeinOnline

Subscribe to the HeinOnline Blog to stay in the know with HeinOnline and to learn about interesting topics like this one. Don’t forget to connect with us on our social media platforms: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube!