Fifty-three years ago today, the landmark decision of Miranda v. Arizona significantly impacted law enforcement procedure, establishing that criminal suspects must be advised of their rights before being taken into police custody. The ruling held that if defendants are not informed of their right to remain silent and consult with an attorney, statements made while in police custody cannot be admissible as evidence.

Though the language may vary between jurisdictions, the “Miranda warning” has become so ingrained in U.S. society due to its portrayal in film and television that many can recite the common phrasing offhand. Lesser known, perhaps, are the details about the case that started it all. Explore the Miranda v. Arizona case first-hand in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library and other databases.

Before We Get Started:

Don’t miss out! Make sure you have the databases we’ll be mentioning in this post. Follow the links below to start a trial today:

“You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you.”

The Case That Started It All

On March 13, 1963, police in Phoenix, Arizona arrested a man named Ernesto Miranda based on circumstantial evidence connecting him to the recent kidnapping and rape of a young woman. After a two-hour police interrogation, Miranda offered a brief confession to the rape charge and was subsequently asked to sign a written version. Though the confession differed from the victim’s account in various respects, it was later presented as the main piece of evidence in Miranda’s trial. Despite the fact that (1) the victim could not identify Miranda in a line-up, (2) no witnesses were called, and (3) the rest of the evidence was circumstantial, Miranda was convicted of the rape and kidnapping and sentenced to 20-30 years’ imprisonment on each charge.

There was just one problem with Miranda’s confession—he was never informed by police that he could remain silent or consult with an attorney before and during the interrogation. Based on this oversight, Miranda’s lawyer objected to using the defendant’s confession as evidence, claiming that it could not be considered voluntary. This objection was overruled, but Miranda’s lawyer went on to file an appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court after his client’s conviction. The case would ultimately be presented before the U.S. Supreme Court as the consolidation of four cases related to the violation of Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights while in police custody.

Discovering Miranda Rights in HeinOnline

When Miranda v. Arizona reached the Supreme Court in 1966, the Court ruled that no confession is admissible under the Fifth or Sixth Amendments unless a suspect is first made aware of his rights and voluntarily chooses to waive them. Among numerous rights related to criminal legal procedure, the Fifth Amendment created protections against self-incrimination by stating “nor shall [any person] be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself.” The Sixth Amendment further established the right to counsel for any accused person. The landmark decision based on these two amendments overturned Miranda’s previous conviction, but he would be retried and convicted once again in 1967.

Users can view the full Supreme Court case, the related amendments, and relevant documents in HeinOnline.

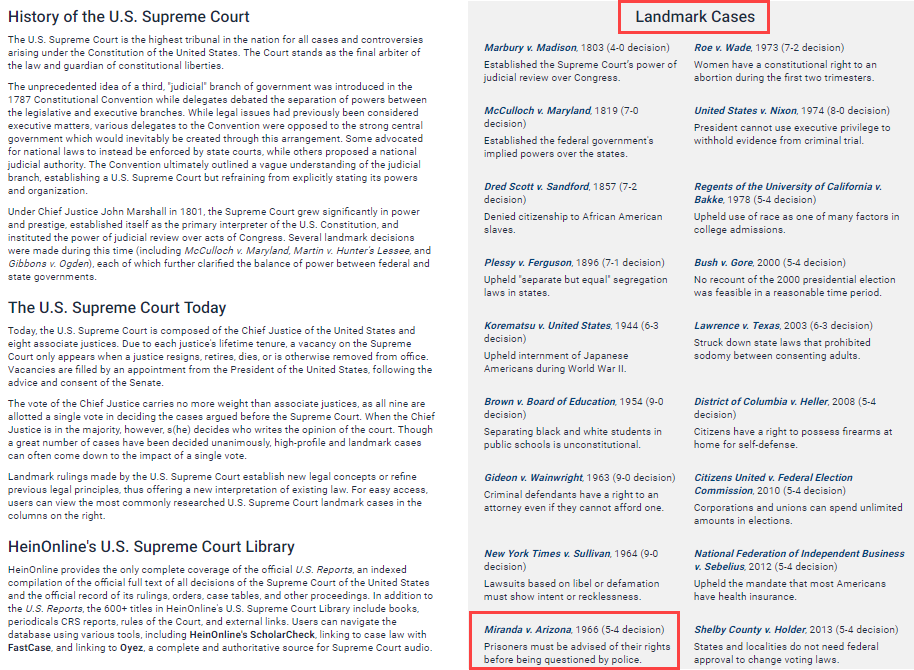

Easily find Miranda v. Arizona in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. The new and improved database home page now provides an overview of the Supreme Court along with a list of the most-researched landmark cases in chronological order. Look through the list to find Miranda v. Arizona right on the front page.

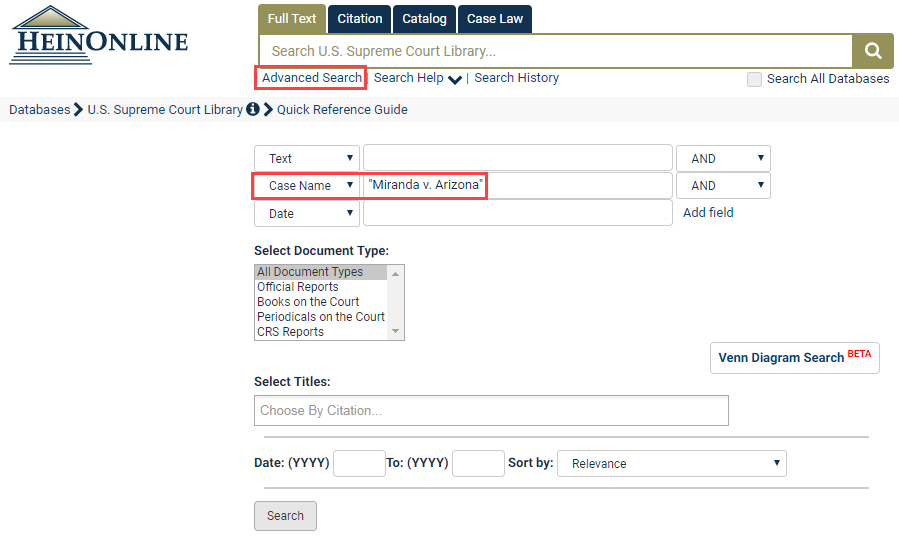

Alternatively, users can run an Advanced Search, hyperlinked in blue under the main search bar. Next to Case Name, type “Miranda v. Arizona” to view one result.

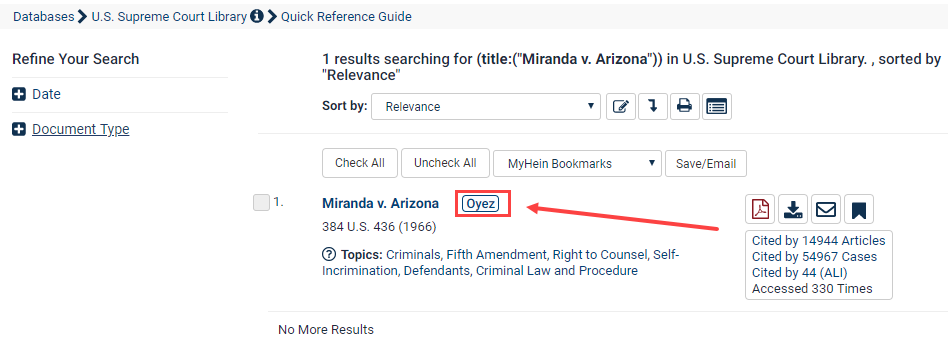

Within the list of results, users will also see a button marked “Oyez” next to the case name.

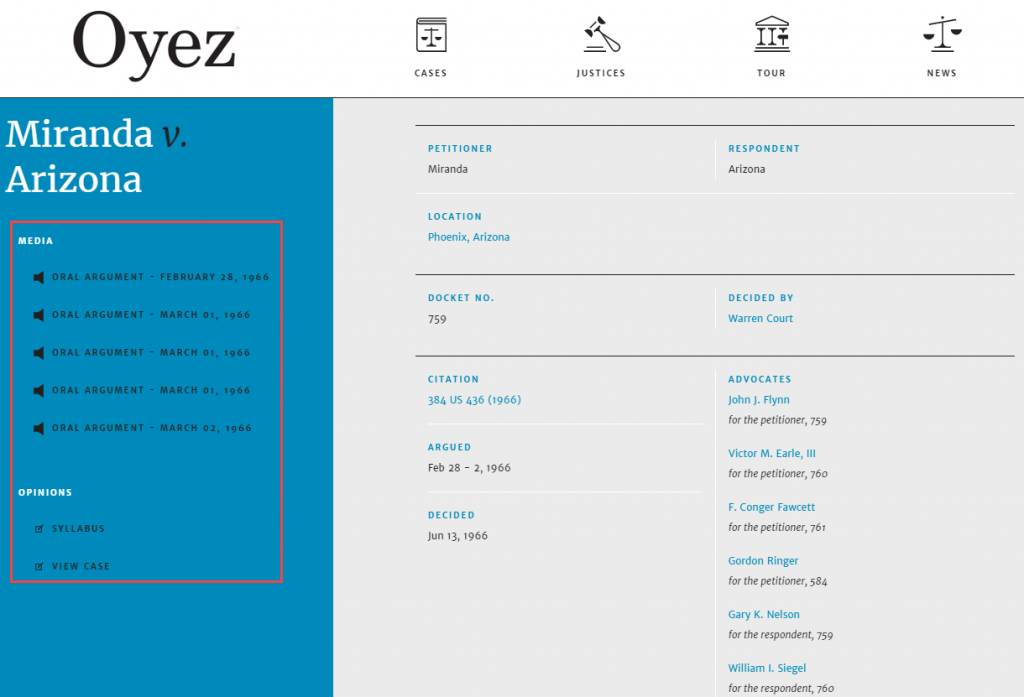

Oyez is a free law project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law dedicated to making Supreme Court case law available to everyone. A multimedia archive, Oyez is a complete and authoritative source for all of the Supreme Court’s audio since the installation of a recording system in October 1955. The Oyez website offers transcript-synchronized and searchable audio, easily understandable case summaries, illustrated decision information, and opinions. Oyez also has detailed information on current and past Supreme Court justices and offers a panoramic tour of the Supreme Court building. In HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library, links to Oyez are available within search results or from a document’s table of contents.

Select the “Oyez” button next to the case name in the search results to view the multimedia options for Miranda v. Arizona.

Find the Fifth and Sixth Amendments in the current U.S. Constitution by navigating to HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. Select “United States of America” from the blue drop-down box at the top of the country list. Click “Constitutions and Fundamental Laws” and then “Constitution of the United States of America” to view the “Basic Reference Editions of the Constitution.” Choose the most current edition (2016) to find the Fifth and Sixth Amendments.

Finally, perform a basic full-text search in the Law Journal Library to find scholarly articles which comment on the Miranda case. Enter “Miranda v. Arizona” AND “police custody” into the main search bar to bring up nearly 2,000 related results. Relevant works listed in the results include:

- Constitutional Law – The Rights of Criminal Suspects in Subsequent Custodial Interrogations

- Being in Police Custody: A Question of Fact or Law

- Sensitive Military Intelligence: Reconsidering Fifth Amendment Waivers

- Access to Counsel when in Policy Custody

Have you ever found yourself asking the same questions over and over?

- What’s going on in the world today?

- How do we know what we know about history?

- What is the extent of HeinOnline’s available content?

- How does one effectively research turtles and/or turtle law?

Discover the answers to these questions and more by clicking the Subscribe button in the upper right-hand corner of this post.

Like what you see? Don’t forget to connect with HeinOnline on our social media platforms: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.