More than 170 years ago, the course of American history was forever changed when millwright James W. Marshall discovered gold in the new U.S. territory of California. The discovery sparked an influx of travelers to the territory, rapidly increasing the area’s population and directly contributing to California’s eventual statehood. Keep reading to learn more about the gold rush and its role in the formation of “the Golden State.”

Users can find all documents relating to the formation of California in HeinOnline’s newest database, State Constitutions Illustrated. The most comprehensive state constitution research platform available, the database holds nearly 10,000 current and historical constitutions for all fifty states, extensive pre-statehood primary material, more than 1,000 books related to each state’s constitutional history, and more. Each month, HeinOnline adds new and expanded content to this database to further enhance your state research.

Don’t miss out on this essential database for studying American history and law. Follow the link below to learn more about your access options!

Pre-Gold California

The interior of California was first discovered in the 1760s by Spanish explorer Gaspar de Portolá. Over the next few decades, Spanish military forces established several forts and smaller towns in the area. In 1821, however, the Mexican War of Independence from Spain culminated in the Treaty of Córdoba, creating the Mexican Empire and putting the territory of California under its jurisdiction.

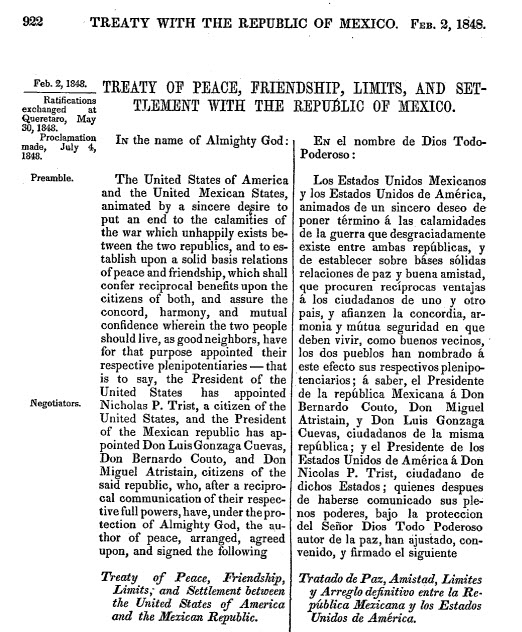

In 1845, the United States defied the Mexican government by annexing the territory of Texas, initiating the Mexican-American War in 1846. Two years later, in 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war, compelling Mexico to cede its northern territories—including California.

The Gold Rush

An Unexpected Discovery

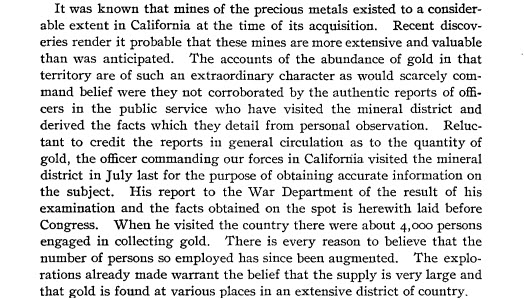

Before the treaty was officially signed, German-born businessman John Sutter hired James W. Marshall to build a sawmill along the American River in Coloma, California. The sawmill would provide the necessary lumber for a new city that Sutter planned to build on his property. Just one week before the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Marshall noticed what appeared to be gold nuggets on the banks of the river. Sutter attempted to keep the discovery quiet, but newspaperman Samuel Brannan soon publicized the find throughout the nearby settlement of San Francisco. A few months later, the East Coast–based New York Herald had reported the discovery. By December of 1848, the California gold was given even more attention when mentioned in U.S. President James K. Polk’s State of the Union address.

The 49ers

Seeking fortune, people in and out of the United States flocked to the California territory. Known as “49ers” (due to the year, 1849), the individuals faced a challenging and, at times, life-threatening journey. Most East Coast gold-seekers traveled by sea, around the tip of South America (a five-month trip), while others sailed to the Isthmus of Panama, traversing the thick jungles that covered the strip until they reached the Pacific side. Land routes through the United States included the treacherous California Trail, laid out decades earlier by fur traders. Merchants and fortune-builders caught by “gold fever” boarded their own ships from Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, and China alike.

Neither land nor sea was safer, as each method brought its own dangers—diseases such as cholera and typhoid fever, attacks from wild animals or local natives, or accidental shipwreck are just a few examples. Regardless, the promise of gold outweighed the risk involved, and by the end of 1849, the non-native population of the California territory had risen by 400%.

Establishing the 31st State

California Constitutional Convention of 1849

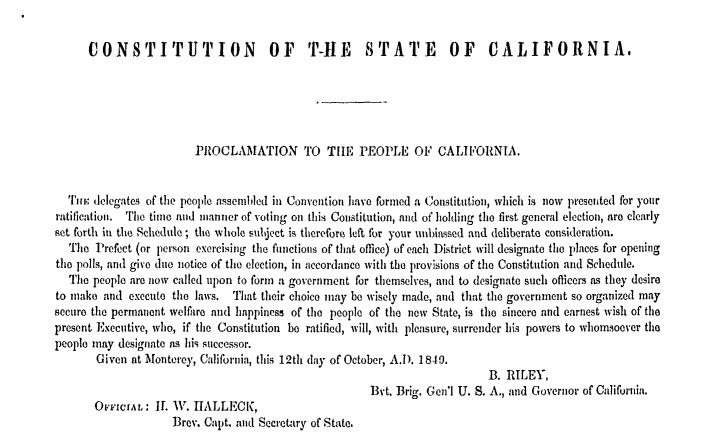

The rapidly increasing population of California led to a demand for a representative government, rather than the military government which had been in place since the Mexican-American War. In June of 1849, General Bennett C. Riley—the last military governor of California—issued a proclamation to initiate a Constitutional Convention made up of elected representatives. Consisting of forty-eight delegates chosen of primarily pre–Gold Rush settlers, the Convention gathered to write California’s first constitution. Among its provisions, this first constitution outlined the boundaries of the territory, set up a statewide system of education, outlawed slavery, and incorporated the right for women to own and control property.

The Compromise of 1850

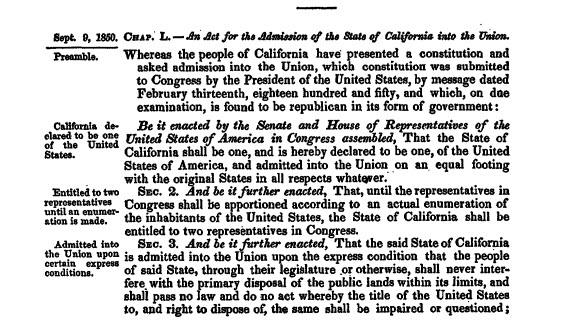

Meanwhile, Congress had been disputing the slave and free state status of its new territories ever since the Mexican Cession. Many Southerners promoted the expansion of slavery into the new lands, while Northerners adamantly disagreed. In 1850, Senator Henry Clay combined a series of proposals into one bill, framing it as a compromise. In his plan, California would be admitted as a free state, Texas would surrender its northwestern land for the creation of New Mexico and Utah, slave trade would be banned in Washington, D.C., and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 would be supported by new legislation requiring federal officials to return escaped slaves to their masters. Following the passage of this package of bills (now known as the Compromise of 1850), word was brought to San Francisco in October of 1850 that California had officially become the 31st American state.

Like what you see and want more? Discover fascinating historical content, exciting HeinOnline updates, and useful tips and tricks when you subscribe to the HeinOnline Blog. Brighten up your inbox by following the link below!