This month, HeinOnline continues its Secrets of the Serial Set series with a look back on the disastrous sinking of the RMS Titanic.

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative monthly blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Documents from additional HeinOnline databases have been incorporated to supplement research materials for non-U.S. related events discussed.

These posts have been so informative; they enable both patrons and staff to understand what the Serial Set is and how invaluable it is to all kinds of research.

The U.S. Congressional Serial Set is considered an essential publication for studying American history. Spanning more than two centuries with more than 17,000 bound volumes, the records in this series include House and Senate documents, House and Senate reports, and much more. The Serial Set began publication in 1817 with the 15th Congress, 1st session. U.S. congressional documents prior to 1817 are published as the American State Papers.

The Serial Set is an ongoing project in HeinOnline, with the goal of adding approximately four million pages each year until the archive is completed. View the current status of HeinOnline’s Serial Set project below.

Laying the Groundwork

The Cradle of Humankind

In the distant past, the southernmost tip of Africa was a center of human evolution. As humankind appeared and developed, the land was soon discovered to be a rich depository of natural resources that attracted migrants from all over the continent. By the 1400s, the south African coast was dominated by Bantu-speaking peoples who had migrated from other parts of Africa approximately a thousand years earlier.

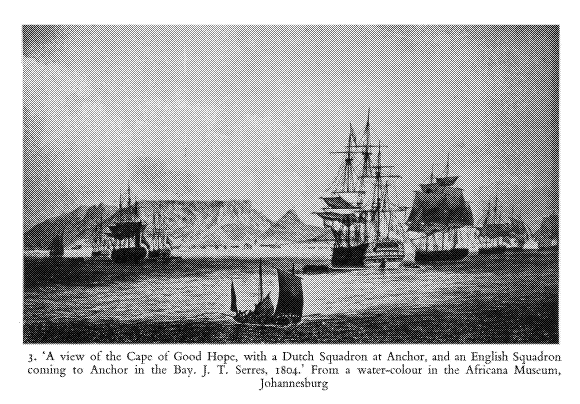

It wasn’t long before the dawn of the Age of Discovery led Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias to south African shores. Maritime giants, the Portuguese traveled the coast throughout the 15th century, at times claiming land as their own by erecting padrões—large stone pillars topped with a cross and inscribed with the royal coat of arms.

Dutch Colonization

However, by the early 1600s, the dominance that Portugal once had over the seas began to decline, threatened by an increase in traveling Dutch traders. These explorers recognized the potential of the coast as a convenient haven for those navigating the sea route to India. Under the command of navigator Jan van Riebeeck, the Dutch East India Company (an amalgamation of several trading companies) built the first settlement on the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.

Soon the Cape was bustling with a large population of former company employees and thousands of their imported slaves, along with the indigenous peoples already residing there. The relationships between some of these white Dutch Christian colonists and nonwhite slaves and indigenous peoples soon formed some of the earliest mixed-race communities in the area. Their descendants would later become known as “Afrikaners.”

The British Empire Steps In

The end of the Napoleonic Wars in the late 18th century saw the cession of South Africa to British rule. The formerly Dutch land was incorporated into the British Empire, leading to the migration of thousands of British settlers.

This influx of newcomers led to the establishment of visibly separate communities: a primarily white, urbanized and, in many respects, “elite” Cape Town; the nonwhite slaves of that community; a countryside smattering of many white and mixed-race Afrikaners; and finally, established indigenous tribes. Racial differentiation became deeply entrenched in both areas, and slaves and indigenous people were soon required by British colonial law to carry a pass when moving about. Even when the United Kingdom abolished slavery throughout the empire in 1833, South African legislation simply changed the status of slaves to that of “indentured laborers,” but kept the system largely the same.

While many Afrikaners grew dissatisfied with British rule, indigenous tribes (the Zulu people, in particular) expanded their own domain and power. The discovery of diamonds in the late 19th century fueled British efforts to control “inferior” populations even further, leading to war and eventual Zulu and Boer (Afrikaner) defeat.

The Union of South Africa

The British tried for years to anglicize both the Afrikaners and indigenous tribes, but many continued to feel hostile toward the empire—particularly black and “colored” (mixed) people who remained marginalized in society. In 1892, the Franchise and Ballot Act raised the property franchise qualification, disenfranchising many poor white and most nonwhite voters. Two years later, the Glen Grey Act limited the amount of land native Africans could hold.

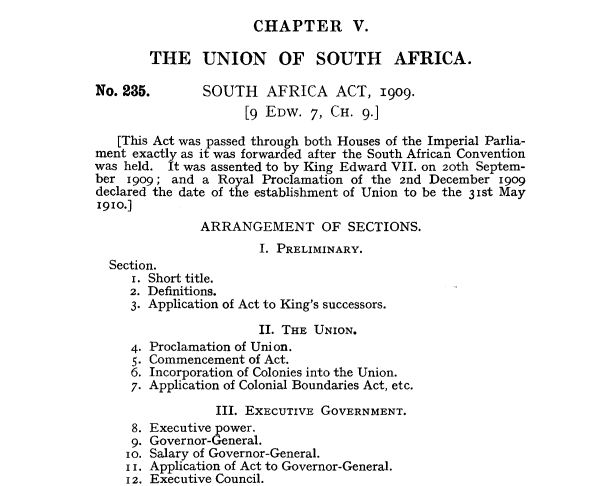

Despite the opposition within its South African colonies, Britain moved ahead with plans for unification. In 1909, the South Africa Act brought the four existing colonies together as the self-governing Union of South Africa, garnering international respect for the new country and global status equivalent to the British dominions of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

The Union of South Africa continued down the path of oppression of nonwhites with a slew of legislation geared toward segregation. The South Africa Act itself effectively gave white people complete political control over all other racial groups and ultimately removed the right of blacks to sit in parliament. The Native Land Act three years later prohibited the trade of lands between whites and natives, as well as black tenant farming on white-owned land. The 1926 Colour Bar Act then prevented black mine workers from practicing skilled trades.

The Institution of Apartheid

South Africa After World War II

The swift economic development precipitated by World War II, combined with the ban on tenant farming and sharecropping, pushed large numbers of black workers to industrial centers. In spite of this, the South African government made no equivalent development in housing and services, resulting in overcrowding, a rise in crime, and general discontent (primarily from whites). Meanwhile, the Herenigde Nasionale Party (Reunited Nasionale Party) rose to prominence, supported by some Afrikaners and promoting the idea that Western liberalism had boosted the position of nonwhites.

The National Party soon took on a new policy—the systematic, legal organization of individual rights and privileges according to race. The policy was named apartheid, after the Afrikaans word for “separateness,” and became the bedrock of Afrikaner politics for the next few decades.

Legalizing Segregation

The National Party became popular with farmers and manual laborers, defeating the oft-described “affluent” United Party in nearly every rural district. In a turning point for South African history, Daniel François Malan became the first nationalist Prime Minister in 1948. His goal? To fully implement the apartheid philosophy, even as the rest of the post-World War II world was moving further away from racism and segregation.

In the decades to follow, multiple apartheid segregation laws would be passed.First, the Population Registration Act of 1950 classified every South African individual into a racially defined “population group.” This act provided the foundation for the apartheid legislation to follow, which included, among many others, an act to segregate public areas and vehicles, an act to limit the places in which blacks were permitted to work, and an act that forbade marriages between whites and nonwhites.

Further, the government established a way to limit ethnic groups to a specific territory. Blacks in particular were classified as residents of bantustans—what the government considered to be their traditional tribal homelands. This removed black people from the South African political arena, but still allowed the government to claim that they had full political rights. The Black Homeland Citizenship Act of 1970 took this further, stripping black South Africans of their country citizenship and instead declaring them citizens of these independent homelands, ensuring a demographic majority of white people. All in all, between 1960 and 1983, approximately 3.5 million black Africans were removed from their homes and forced into segregated neighborhoods.

Resistance to the System

South African Resistance

Though government leaders claimed that apartheid bettered the lives of all races, resistance was apparent across various sectors of South African society. For decades throughout the 20th century, uprisings and protests occurred and were met with police brutality, which only fueled the fire of the resisters. In 1949, the African National Congress (ANC) became the primary opponent of apartheid when the organization’s youth wing took over, pushing for more radical ideals. Led by Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, and Oliver Tambo, the ANC launched strikes, boycotts, and other displays of civil disobedience such as burning their passbooks (required identification for all black citizens traveling outside of their designated areas).

Demonstrations from the ANC and other organizations sometimes led to violent encounters with South African authorities. Notably, on March 21, 1960, thousands of protesters went to the Sharpeville police station, asking to be arrested for not carrying their passbooks. In a panic, young members of the South African Police opened fire on the protesters, setting off a chain reaction that ultimately killed 69 blacks and injured nearly 200 others. Following the massacre, more than 18,000 people were arrested, including prominent anti-apartheid activists and leaders of the ANC, including Nelson Mandela himself.

The Efforts of Nelson Mandela

Mandela was sentenced to five months in prison, but this did not deter him from future anti-apartheid activism. He used the time to organize an All-African Conference, to be held in March of the next year. Once released, he took to donning disguises and holding secret meetings to organize more protests, strikes, and boycotts. Later, inspired by guerrilla warfare tactics from Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, Mandela began to steer the ANC toward developing a controlled armed resistance. With others, he formed a militant group known as MK; together, they planned to use violence to sabotage government activities in a way that would cause minimal civilian casualties, such as bombing military installations and power plants.

Mandela was captured on August 5, 1962 and charged with leaving the country without permission and inciting worker strikes. He was initially sentenced to five years’ imprisonment; however, after raiding an ANC safe house, police found evidence that Mandela and his comrades had conspired to sabotage and violently overthrow the government. Mandela admitted to the sabotage but not to guerrilla warfare, and gave a three-hour long speech that promoted his political cause. Despite international calls for release, Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment.

International Resistance

Meanwhile, reports of the goings-on in South Africa traveled well beyond its borders, reaching the United Nations and therefore, the reigning global superpowers: the United States and the Soviet Union. The 1960 Sharpeville massacre, in particular, was a turning point for the United Nations’ view of apartheid, causing the Security Council to call for the country to abandon racial discrimination. With no response, the United Nations Special Committee Against Apartheid was established and passed Resolution 282, a call for all member states to refrain from sending arms to South Africa. An international anti-apartheid movement began to form.

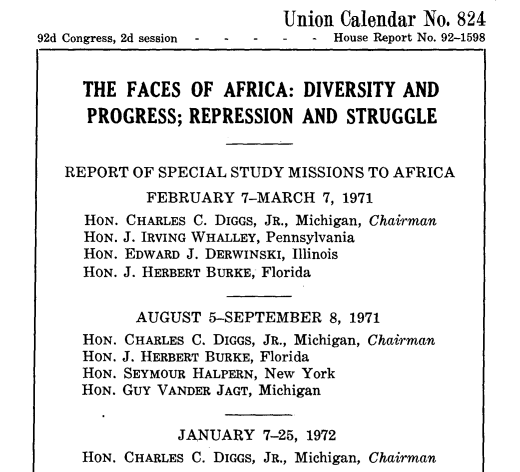

In the United States specifically, the country’s ongoing domestic civil rights movement and simultaneous fear of Cold War Communism prohibited American activists from fully supporting the South African struggle for racial liberation. In 1969, two members of the Committee on Foreign Affairs investigated the situation in southern Africa. Upon their return, they gave their report on the stark black-white crisis there but also noted the “even more ominous” issue of significant Communist involvement in the African struggle for freedom.

A second report in 1972 noted that Southern Africa was “a tinderbox which could at any time be sparked into flames” and that “a racial holocaust” was imminent. In 1976, following the Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act, the Committee on International Relations called for President Gerald Ford not to recognize Transkei, the first of the bantustans slated for independence.

But it would take another decade and much debate for the United States to formally divest from South Africa. In 1986, Congress launched a bipartisan initiative to place economic sanctions on the country, and outlined five preconditions necessary for lifting the sanctions (including the release of Nelson Mandela).

The bill was passed in both the House and the Senate, but was vetoed by President Ronald Reagan. The President called the initiative “economic warfare,” and warned that it would just lead to greater strife for the black majority. Reagan offered instead to impose sanctions via executive order, but the veto was still judged harshly both within the U.S. and in the international community.

A week later, for the first time in the 20th century, Congress voted to override a president’s foreign policy veto. On October 2, the law was passed as the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986.

The End of Apartheid

By the end of the 1980s, South Africa’s reputation and relationship with other nations began to decline, particularly with this new stance from the United States. The apartheid regime began to take steps toward meeting the preconditions laid out by the U.S., commencing a series of negotiations between the governing National Party and the African National Congress and other political organizations.

The first significant steps toward the end of apartheid took place in February 1990 when, in his speech at the opening of Parliament, President F. W. de Klerk announced a repeal of the ban on the African National Congress and the release of its leader Mandela. A crucial element to the negotiations was the creation of a new constitution, on which Mandela and de Klerk worked together. Later that year, de Klerk and Mandela were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to peacefully end apartheid and introduce democracy to South Africa.

On April 27, 1994, South Africa held the first election in which all races were allowed to participate, with universal adult suffrage. The African National Congress party won with nearly 63% of the vote, and the first act of the new National Assembly was to elect Nelson Mandela as President. As the country’s first black chief executive, Mandela signed the new South African constitution on December 10, 1996 at Sharpeville—the site of the tragic massacre more than three decades earlier.

Help Us Complete the Project

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us, please contact Shannon Hein at 716-882-2600 or shein@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give special thanks to the following libraries for their generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

- Wayne State University

- University of Utah

- UC Hastings

- University of Montana

- Law Library of Louisiana

- George Washington University

- University of Delaware

We will continue to need help from the library community to complete this project. Download this Excel file to see what we’re still missing.