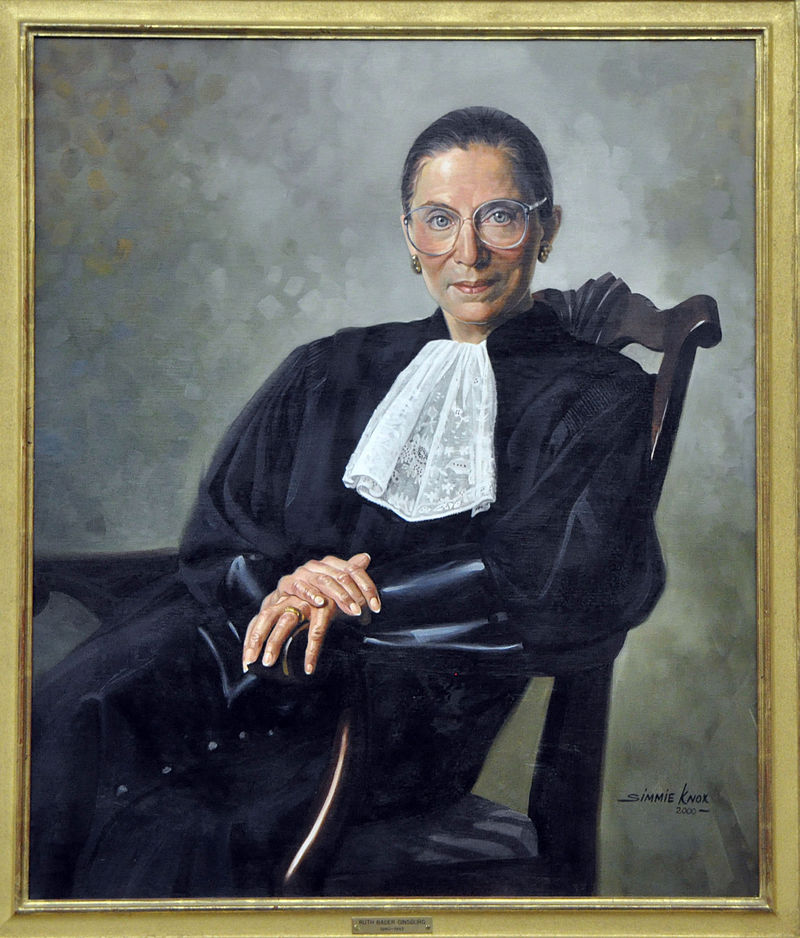

This past weekend, the nation lost one of its biggest social justice warriors, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. After serving on the Supreme Court of the United States for nearly three decades, Ginsburg passed away from complications of metastatic pancreatic cancer at the age of 87. She was the second female justice, after Sandra Day O’Connor, to serve on the Court and was well known for her fiery dissents, her tireless fight for gender equality, and her ability to overcome adversity. Although she weighed only 100 lbs, this 5’1″ feminist icon was larger than life.

The Beginning of Greatness

Ruth Bader Ginsburg attended Cornell, where she met her husband Martin D. Ginsburg. She graduated in 1954 with a bachelor of arts degree in government and was the highest-ranking female student in her graduating class. In 1956, Ginsburg enrolled at Harvard Law School as one of nine women in a class of nearly 500 men while juggling motherhood and later transferred to Columbia for her final year of law school. Ginsburg was the first woman on the editorial board of two prestigious law journals: the Harvard Law Review and Columbia Law Review.

Later that year, her husband was diagnosed with testicular cancer. While he underwent extensive treatment, Ginsburg took care of her daughter and husband, while continuing her studies in law. She graduated in 1959 with her law degree, tying for first in her class.

One thing that I did feel in law school was that if I flubbed, that I would be bringing down my entire sex. That you weren’t just failing for yourself, but people would say, “Well, I did expect it of a woman.”

Ginsburg continued to face gender discrimination at the start of her legal career. Despite her outstanding academic record and a strong recommendation from Albert Martin Sacks, a professor and later Dean of Harvard Law School, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter rejected her for the clerkship position because of her gender. Eventually, Ginsburg clerked for Judge Palmieri of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York City for two years.

In 1963, Ginsburg became a professor of law at Rutgers Law School, at a time when there were fewer than twenty female professors in the United States. Again, she faced gender discrimination when she was informed that she would be paid less than her male colleagues, because her husband had a well-paying job.

In 1972, she co-founded the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and a year later became the Project’s chief lawyer. Over the span of three years, she argued six gender discrimination cases before the Supreme Court, winning five and advancing women’s rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.

The Equalizer

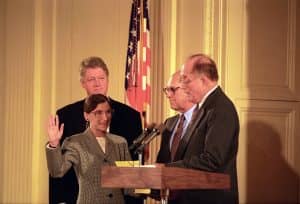

When President Bill Clinton nominated Ginsburg in 1993 to fill the seat vacated by Justice Byron White, she was viewed as a moderate, but in time became the senior member of what is sometimes referred to as the Court’s “liberal wing.” Clinton was looking to diversify the Court, and Ginsburg did just that, becoming the second female and only sixth Jewish justice to serve. Justice Ginsburg authored countless opinions over the years, many of which influenced legislation. Here are some notable ones:

United States v. Virginia

In 1996, Ginsburg wrote on behalf of the majority in a 7-1 decision that stated the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause with their male-only admission policy. VMI was the last all-male public university in the United States before this ruling. This decision served as a milestone in women’s rights in education and admission policies.

Shelby County v. Holder

In 2013, Ginsburg’s scorching dissent in this case led to her nickname, “The Notorious R.B.G.,” coined by a New York University law student. The majority opinion was delivered by Justice John Roberts, overruling a key provision in the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that required jurisdictions with a history of discrimination to undergo federal oversight before approving any changes in the voting procedure. Ginsburg wrote “throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.

This case struck home for Ginsburg, as it revolved around gender discrimination and civil rights, something she herself fought for early on in her career. In 2007, Lilly Ledbetter sued her employer, Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, for receiving lower compensation than her male colleagues. Although she initially won the case, it was appealed up to the Supreme Court, which reversed the original decision, ruling that Ledbetter’s claim was made past the 180-charging period, and she therefore could not sue under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

In order to make her disagreement known, Ginsburg read her dissent from the bench, an unorthodox move, and was quoted as saying, “The ball is in Congress’s court … to correct this Court’s parsimonious reading of Title VII.” Two years later, Congress passed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, which states that the 180-day statute of limitations for filing an equal-pay lawsuit regarding pay discrimination resets with each new paycheck.

Dissents speak to a future age. It’s not simply to say, “My colleagues are wrong and I would do it this way.” But the greatest dissents do become court opinions and gradually over time their views become the dominant view. So that’s the dissenter’s hope: that they are writing not for today, but for tomorrow.”

Gonzales v. Carhart

This landmark decision in 2007 upheld the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003 with a 5-4 vote. The majority ruled that the act was not an undue burden on abortion rights. Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote the majority opinion, stating that the procedure was never necessary to protect a pregnant woman’s health. In Ginsburg’s dissent, she said, “The court deprives women of the right to make an autonomous choice, even at the expense of their safety. This way of thinking reflects ancient notions about women’s place in the family and under the Constitution—ideas that have long since been discredited.”

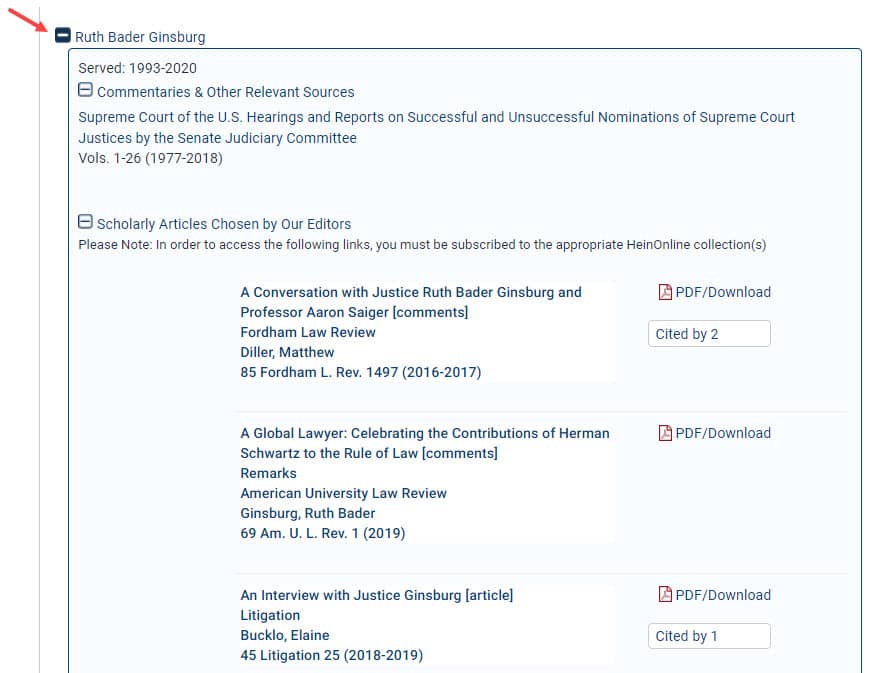

A Seat in HeinOnline

If you want to research Ruth Bader Ginsburg, HeinOnline has a wealth of information. Navigate to the History of U.S. Supreme Court Nominations database and choose the Browse By Justice subcollection. Select Ruth Bader Ginsburg to see a list of commentaries and other relevant sources, as well as scholarly articles chosen by our editors. These articles include those written by Ginsburg herself and those written about Ginsburg.

Click on Ginsburg’s name from within one of her authored articles to view her author profile page in HeinOnline. It’s no shock that she ranks 193 in our ScholarRank’s Top 250 Authors. Here are Ginsburg’s top 5 cited articles in HeinOnline:

Some Thoughts on Autonomy and Equality in Relation to Roe v. Wade

North Carolina Law Review, Vol. 63, Issue 2 (January 1985), pp. 375-386

63 N.C. L. Rev. 375

Speaking in a Judicial Voice

New York University Law Review, Vol. 67, Issue 6 (December 1992), pp. 1185-1209

67 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1185

Remarks on Writing Separately

Washington Law Review, Vol. 65, Issue 1 (January 1990), pp. 133-150

65 Wash. L. Rev. 133

Gender and the Constitution

University of Cincinnati Law Review, Vol. 44, Issue 1 (1975), pp. 1-42

44 U. Cin. L. Rev. 1

Affirmative Action: An International Human Rights Dialogue

Cardozo Law Review, Vol. 21, Issue 1 (October 1999), pp. 253-282

21 Cardozo L. Rev. 253

What’s Next

This Friday, Justice Ginsburg’s casket will be placed in National Statuary Hall, making her the first woman in history to lie in state in the U.S. Capitol. Ginsburg is a woman of remarkable resilience, strength, courage, and intelligence. May she rest in peace, and may her legacy live on.

Ginsburg’s death has sparked a political debate over the vacancy on the Court, just weeks before Election Day. President Trump has said he expects to announce his nominee this weekend. A report issued in 2018 by the Congressional Research Service found that the average time from nomination to confirmation was more than two months, with the exception of Justice John Paul Stevens, who was confirmed in just 19 days.

Fight for the things that you care about. But do it in a way that will lead others to join you.

Subscribe to the HeinOnline blog to stay in the know. We will be featuring this nominee in an upcoming blog post.