In the wake of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death, some Democrats have pushed the idea of expanding the number of justices on the Supreme Court. The concept—known as “court packing”—has caught fire in some circles, particularly following the announcement of President Trump’s official nominee pick, Amy Coney Barrett. A conservative-leaning circuit judge, Barrett’s confirmation would reshape the ideology of the Supreme Court and could hinder it from making more liberal decisions.

Why does the Supreme Court only have nine justices, anyway? What is court packing, really? Is it a feasible option for the Democrats? Why should we care? Allow HeinOnline to help answer all these questions and more using the databases below:

- Law Journal Library

- U.S. Congressional Serial Set

- U.S. Federal Legislative History Library

- U.S. Statutes at Large

- U.S. Supreme Court Library

- World Constitutions Illustrated

A Brief History of the Supreme Court

The unprecedented idea of a third, “judicial” branch of government was introduced in the 1787 Constitutional Convention while delegates debated the separation of powers between the legislative and executive branches. While legal issues had previously been considered executive matters, various delegates to the Convention were opposed to the strong central government which would inevitably be created through this arrangement. Some advocated for national laws to instead be enforced by state courts, while others proposed a national judicial authority.

Ultimately, a judicial branch of government was written into the U.S. Constitution, vaguely outlined in the third article of the document. Article III, Section 1 states that the “judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and such inferior Courts,” and that the judges “shall hold their offices during good behaviour”—interpreted to mean that they cannot be discharged unless impeached and convicted. Article II, Section 2 then awarded the power to nominate Supreme Court justices to the President, with the “advice and consent” of the Senate.

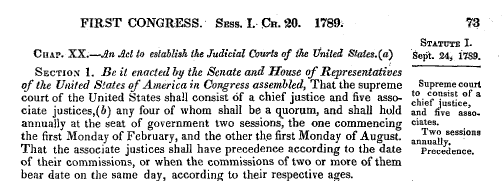

The rest of the Court’s powers and organization was left up to Congress. In 1789, the first session of the First Congress passed the Judiciary Act, clarifying the nature of this new third branch. Among its provisions, the act established six seats on the Court (one Chief Justice, and five Associate Justices). President George Washington immediately submitted his nominations, and all were confirmed by the Senate in two days.

Later Development of the Court

Under Chief Justice John Marshall in 1801, the Supreme Court grew significantly in power and prestige, established itself as the primary interpreter of the U.S. Constitution, and instituted the power of judicial review over acts of Congress in the landmark case Marbury v. Madison. Other landmark decisions during Marshall’s tenure, including McCulloch v. Maryland, Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, and Gibbons v. Ogden, further clarified the balance of power between federal and state governments.

Throughout the 1800s, Congress altered the size of the Supreme Court five times, first increasing the number of justices to seven in 1807, then to nine in 1837. By Abraham Lincoln’s presidency, Congress had expanded the number of seats to ten. However, in what would be an ongoing battle with the next president, Andrew Johnson, Congress lowered the number back to seven in 1866, preventing Johnson from appointing any new justices. In 1869, after Ulysses S. Grant was elected president, Congress once again raised the number of Supreme Court justices to nine, where it has remained ever since.

Today, the U.S. Supreme Court stands as the highest tribunal in the nation for all cases and controversies arising under the Constitution of the United States. The Court stands as the final arbiter of the law and guardian of constitutional liberties. Due to each justice’s lifetime tenure, a vacancy on the Supreme Court only appears when a justice resigns, retires, dies, or is otherwise removed from office.

The Impact of RBG’s Supreme Court Vacancy

Now, with Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death, the Trump Administration has the opportunity to confirm a new justice before Election Day.

Why does that matter? With Ginsburg, the Court was relatively balanced at a 5-4 conservative majority, meaning that only one liberal vote from an otherwise conservative justice was necessary to change the outcome of a case. Often, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. provided that swing vote on divisive issues—for example, in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, when he voted to uphold the Affordable Care Act. If Amy Coney Barrett—Trump’s young, conservative-leaning pick—is confirmed, however, the Court’s makeup will change to a 6-3 conservative majority. Three of those six conservative justices will have been appointed by Trump, making it much harder for divisive cases to be decided in liberal favor.

Soon after Ginsburg’s death, many Democrats recalled the fact that Congress can alter (and has altered) the size of the Supreme Court for political reasons. Political activists and public officials alike have latched onto the thought with a fervor, and even Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer has now stated that “Nothing is off the table for next year.”

Remembering FDR’s Court Packing Attempt

Will Democrats actually be able to pack the Supreme Court? To begin answering that question, we can look to a famous historical example.

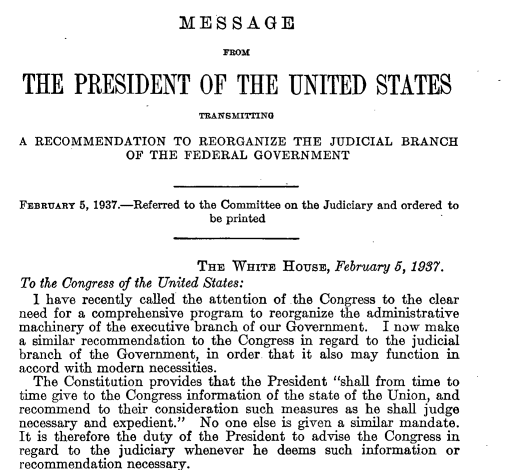

In the late 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt attempted to mitigate the effects of the Great Depression with a series of social programs, financial reforms, federal regulations, and public works projects known as the New Deal. However, the Supreme Court at the time consistently struck down key New Deal legislation. Coming out on top of a landslide election and emboldened by a Democrat-controlled House and Senate, Roosevelt proposed a startling legislative initiative in 1937: offer retirement at full pay for all Supreme Court justices over 70 years old, and for those who refuse to retire, allow the president to appoint an additional justice to the Court.

Making his case for the plan in his ninth Fireside chat, the President called for the infusion of “new blood into all our Courts” and stated that the nation “must take action to save the Constitution from the Court and the Court from itself.” (Readers can also listen to the Fireside Chat here).

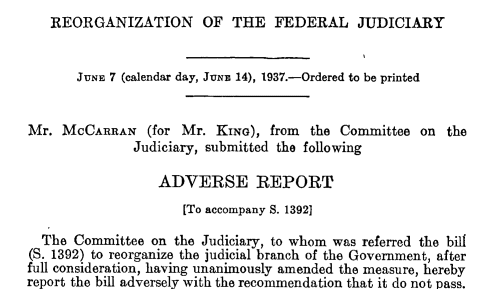

Unfortunately for Roosevelt, however, the bill was met with opposition from both sides of the aisle, and even from Roosevelt’s own vice president, John Nance Garner. As the bill was read in the Senate, Garner reportedly held his nose and gave an animated “thumbs-down” from the back of the room. Roosevelt’s longstanding battle with the Supreme Court soon devolved into a fight between him and his own party.

Then, less than two months later, the Supreme Court handed down three decisions in favor of the New Deal. Roosevelt’s case for reorganizing the Court was shattered. His bill did not pass.

As author Michael Parrish writes, “When the dust settled, FDR had suffered a humiliating political defeat …”, leaving him at odds with both parties. (Parrish, Michael (1983). “The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the American Legal Order.” Washington Law Review. 59: 737).

Peruse a full legislative history of FDR’s attempt to reorganize the Federal Judiciary.

Though its makeup is not expressly written in the Constitution, the Supreme Court and its procedures are naturally conflated with the document. As evidenced by FDR’s 1937 attempt, drastic changes to the Court have been considered in the past a violation of the foundations of our government.

What’s in store remains to be seen, but one thing is clear—the upcoming months could mean drastic change for the judicial branch, the likes of which has not been seen in more than 150 years.

Continue to keep up with hot topics and current events with the HeinOnline Blog. Subscribe today to have posts like this sent right to your inbox.