The holidays are fast approaching. Whether you’re gathering in-person with family or carving individual ham steaks over Zoom, preparations still need to be made, bringing along the usual hassle, chaos, and stress that come from trying to accommodate everyone’s schedules, prepare a meal, and decide whether it’s okay to mute Uncle Jim when he starts talking politics. All this family togetherness can bring on a headache, and you may reach for your trusty bottle of Holiday Acetaminophen to provide some relief. This relief is only obtainable after you rip off the plastic wrapper around the bottle’s neck, battle open the child-proof cap, peel off the inner foil safety seal, peel off the little bits of the seal you didn’t get off the first time, and finally expose the medication within.

While these tamper-evident measures can sometimes feel like an obstacle course, they are there not to aggravate the headache-addled, but instead serve to prevent very real tragedies. These safety measures are actually mandated by federal regulations that came into effect after a series of murders that, nearly forty years later, still remain unsolved.

Death Lurks in the Medicine Cabinet

Wednesday, September 29, 1982. In Arlington Heights, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, 27-year-old Adam Janus felt unwell. He went to a local supermarket and bought a bottle of extra-strength Tylenol and, after arriving home, took two capsules. Minutes later, Adam staggered into his kitchen and collapsed. He was rushed to the hospital, his family following behind with swift worry. Within a matter of hours, Adam was dead. Doctors originally ruled his cause of death a heart attack. Adam’s family, including his brother, Stanley, 25, and sister-in-law, Theresa, 19, gathered at Adam’s home with the rest of the family. Understandably, Stanley was stricken with a terrible grief-induced headache over the sudden death of his brother, an ailment Theresa shared. They found a bottle of extra-strength Tylenol and each took two capsules. Minutes after taking the pills, just as had happened to Adam, they both collapsed. Stanley Janus died that same day, just hours after his brother, with Theresa dying two days later.

The same day that tragedy shattered the Janus family, six miles away, in Elk Grove, Illinois, 12-year-old Mary Kellerman had awoken with all the hallmarks of a bad cold: fever, runny nose, and headache. As many of us would do, she took one innocuous-looking extra-strength Tylenol to ease her symptoms. Moments later, Mary collapsed, dying shortly before 10 a.m. of unknown causes.

Hospital staff, police, and the public health department were already suspicious about the Janus deaths; when first responders connected them to the death of Mary Kellerman, investigators examined the remaining Tylenol in both households. Both bottles contained pills that were laced with cyanide.

But investigators’ suspicions, though quickly grasping the gravity of the situation, were forming too late. That same day, Mary Reiner, 27, who the week prior had given birth to her fourth child, collapsed after taking Tylenol. Mary McFarland, 31, also became critically ill after taking some Tylenol at work for a headache; both women died the following morning.

Officials moved quickly, with Tylenol’s makers, Johnson & Johnson, putting out a recall on Friday, October 1st, for all bottles of extra-strength Tylenol in the greater Chicago area. A press conference warning the public of cyanide-tainted Tylenol was aired the same day, but it was too late to reach Paula Prince, 35, who was found dead in her apartment that night, an open bottle of Tylenol on her bathroom vanity. The subsequent investigation would unearth security camera footage of Prince buying a bottle of Tylenol at a Chicago Walgreens on Wednesday night; she had been dead for two days before police discovered her body.

With help from the FBI and FDA, thousands of investigators sampled medication nationwide and probed manufacturing plants to determine the source and scope of the contamination. After clearing Johnson & Johnson of any wrongdoing, their investigation was barreling towards a horrifying but undeniable conclusion: someone was walking into pharmacies and grocery stores to contaminate Tylenol capsules with cyanide. By Tuesday, October 5th, Johnson & Johnson recalled all Tylenol products nationwide—a value of $100 million at the time—and established both a hotline and a $100,000 reward to catch the culprit. The story was an international news sensation, dominating television and radio, with police cars in Chicago patrolling the streets with loudspeakers to broadcast warnings to citizens about the medication.

Congress Hunts a Killer

Two weeks after the deaths of Mary Kellerman and Adam Janus, the House of Representatives held a hearing on whether over-the-counter (OTC) medications should be required to have tamper-resistant packaging. Tamper-resistant packaging in some forms existed in 1982, but there was no federal standard on packaging requirements to ensure its uniform application on products from state to state. With seven people dead and a major staple of household medicine cabinets now both literally and figuratively tainted, pressure was intense from both Congress and the industry to develop ways to restore both public confidence and safety to OTC medicines. Congress scrutinized the FDA for never considering the calamity such a lack of regulations could invite, and the drug industry itself asked for federal action on the issue. The following month, the FDA issued new regulations requiring OTC drug products to be packaged in a way that would make it evident to the consumer if a product had been interfered with, such as packaging pills in blister or strip packs, seals around the product or product container, or breakable caps.

These Extra-Strength Tylenol capsules were packaged in plastic snap-top bottles, with cotton wadding inserted into the neck of the bottle. The bottles were placed inside individual cardboard cartons. Although packaged in compliance with current FDA requirements, neither the bottles nor the cartons were sealed or otherwise fabricated to ensure that access to the product required the destruction or visible disturbance of the package.

Johnson & Johnson led the packaging revolution, developing a triple safety system that became the standard we know today: an outer box with glued flaps, a plastic seal over the cap and bottle neck, and a foil seal under the cap. The second innovation from Johnson & Johnson was the invention of the caplet, introduced in 1984, to replace the hollow capsules that malevolent actors had tampered with in Chicago. The caplet, smaller and solid, was more difficult to violate than a hollow capsule, and it officially replaced the capsule in Johnson & Johnson’s product line in 1986 after a copycat cyanide poisoning killed a woman in Westchester County, NY.

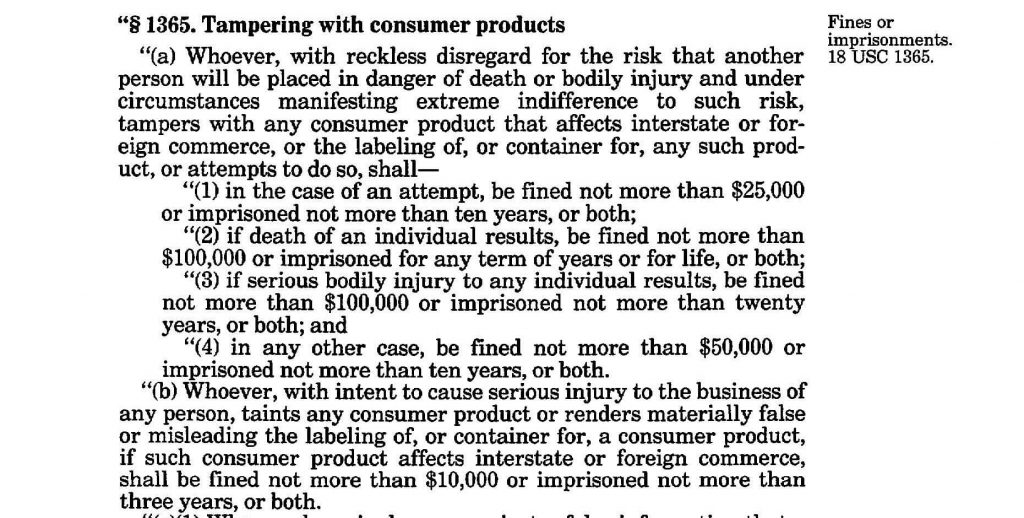

Congress also took action, with a swiftness that may be hard to believe is possible in 2020, passing the Federal Anti-Tampering Act in 1983, which imposed stiff penalties for product tampering.

Stella Nickell was the first person convicted under the Act. In 1988, she was sentenced to two 90-year terms for contaminating Excedrin capsules with cyanide, resulting in the deaths of her husband, Bruce Nickell, and Sue Snow, an unfortunate innocent who purchased Excedrin that Nickell contaminated in an attempt to portray her husband’s death as the result of random product tampering, thus increasing the insurance payout she would receive.

But for the victims in Chicago, justice remains incomplete. To date, no one has been convicted of the murders. Prime suspect James William Lewis was arrested and convicted for attempted extortion of Johnson & Johnson at the height of the panic over the killings, but no clear connection between Lewis and the murders was ever established; Lewis was released from prison in 1995. Unabomber Ted Kaczynski was investigated as a potential suspect in 2011, but investigators have never determined whether he was responsible.

A Daily Dose of Knowledge

The HeinOnline bloggers love coming up with new ways to help users explore HeinOnline and apply the resources within it to a variety of topics, whether it’s strictly academic or ripped from the headlines. Subscribe now and we’ll write you a prescription for posts sent straight to your inbox.