This month, HeinOnline continues its Secrets of the Serial Set series with a look back on the disastrous sinking of the RMS Titanic.

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative monthly blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Documents from additional HeinOnline databases have been incorporated to supplement research materials for non-U.S. related events discussed.

These posts have been so informative; they enable both patrons and staff to understand what the Serial Set is and how invaluable it is to all kinds of research.

The U.S. Congressional Serial Set is considered an essential publication for studying American history. Spanning more than two centuries with more than 17,000 bound volumes, the records in this series include House and Senate documents, House and Senate reports, and much more. The Serial Set began publication in 1817 with the 15th Congress, 1st session. U.S. congressional documents prior to 1817 are published as the American State Papers.

The Serial Set is an ongoing project in HeinOnline, with the goal of adding approximately four million pages each year until the archive is completed. View the current status of HeinOnline’s Serial Set project below.

The Voyage Begins

The Royal Mail Steamer (RMS) Titanic, a passenger liner of Britain’s White Star Line, entered into service on April 2, 1912. At the time of her unveiling, the Titanic was the largest ship in the world. Deriving her name from the Titans of Ancient Greek lore, the liner extended more than 882 feet long and 92 feet wide, and sat at a solid 46,328 gross register tons. Inside, her accommodations and facilities met the highest standards of luxury, with the most expensive first-class suites costing an equivalent of $115,000 today for a one-way trip. Learn about the structure of the Titanic.

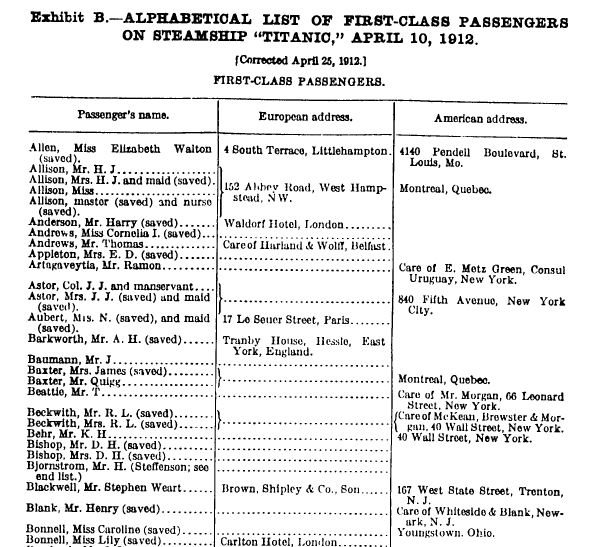

On April 10, 1912, the Titanic embarked on her maiden voyage from Southampton, helmed by Edward Smith (a senior White Star Line captain with forty years’ experience) and manned by a crew with a considerable lack of sailing experience—only 39 out of 892 crew members were able seamen. Before setting course for New York City, the ship picked up an additional 1,320 passengers from Southampton, France, and Ireland, ranging in status from millionaires (First Class) to academics, clergy, and leisure tourists (Second Class) to poor emigrants (Third Class). View a full list of crewmembers, first-class passengers, second-class passengers, and third-class passengers aboard the Titanic.

The Fatal Collision

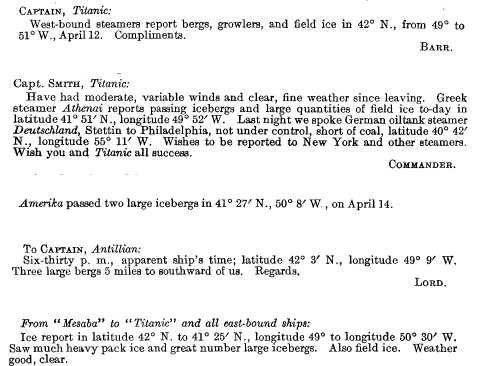

The first three days of the voyage were relatively calm with no significant incidents to speak of. But on April 14, as the Titanic careened through the North Atlantic, radio operators aboard received at least six messages from nearby ships warning of surrounding ice conditions, including icebergs and large swaths of field ice. At least two of these messages (which had trickled in as early as 9:00 a.m.) were relayed to Captain Edward Smith. In response, the captain ordered that the ship redirect farther south; however, he did not reduce the Titanic‘s speed, instead continuing ahead at just 2 knots short of her maximum.

Ice was important to be aware of, certainly, but it was not a dire concern to seamen of the time—after all, just a few years earlier, German liner SS Kronprinz Wilhelm had run head-on into an iceberg and still completed her journey. Just to be safe, Smith ordered his lookouts to keep a close eye out for ice—although it was a tricky task, as there was no moonlight and the crew had misplaced their binoculars.

Blissfully unaware of the perfect conditions for a collision that were currently underway, the Titanic‘s passengers gradually went to sleep as evening drew in. Surrounded by a beautifully calm, glass-like sea, it would have been hard for those on board to imagine any sort of impending doom (though these conditions are now recognized as a tell-tale sign of nearby pack ice).

At 10:30 p.m. ship time, the Titanic received her final ice warning from the SS Californian, a liner that had just come to a stop only a few miles away due to a surrounding ice field. This time, the Titanic‘s radio operator was curt with that of the Californian, rudely cutting him off mid-warning. The Californian operator subsequently packed up for the night and went to bed.

A little over an hour later, one of the Titanic lookouts sounded his bell three times and called up to the bridge with a simple message—”Iceberg, right ahead!” As was the standard, the Quartermaster ordered a complete reversal of direction—a relatively time-consuming and complex task for the giant vessel. In the end, the Titanic avoided a full-frontal collision, but still struck the iceberg along the starboard side as she turned.

To the Lifeboats

Most on board never heard the haunting sound of steel scraping ice, and those who did figured it was a glancing blow. In truth, the damage was seemingly insignificant—only a few narrow tears toward the bottom of the ship, spanning a total area of 12-13 square feet (though initial investigations presumed that the opening must have been at least 300 feet wide). Regardless, within five minutes, the Titanic‘s engines were fully stopped and water was flooding into her boiler rooms several times faster than it could be pumped out.

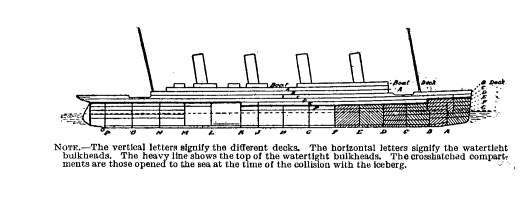

To understand how the Titanic sank, it is important to note the structure of these lower decks. They consisted of sixteen compartments, each separated from the next by a bulkhead that could be sealed with watertight doors. Though extending well above the water line, these bulkheads were not sealed at the top. In her initial design, the Titanic could remain afloat if certain combinations of two, three, or even four of these compartments flooded. However, five flooded compartments would cause the ship’s bow to angle deeper into the sea, causing water to spill across the unsealed top of the bulkheads (like a tipped ice cube tray).

Soon, five (and later, six) compartments completely flooded with water. Surveying the damage, the Titanic‘s builder, Thomas Andrews, informed the captain that the ship had an estimated two hours before she would sink entirely. Learn about how the Titanic flooded in this initial report from the British Government.

Without a public address system, it was up to the ship’s stewards to visit each cabin, door to door, and awaken the sleeping passengers and crew within. With fewer passengers to handle, first-class stewards were much more organized about their efforts, whereas the third-class stewards, forced to manage large crowds of people, were less effective. A general sentiment that the situation was a joke, an inability to hear over the noise of high-pressure steam, and an overall lack of awareness about the severity of the damage made orderly abandoning of the ship that much more difficult.

As the passengers were dealt with, Captain Smith ordered the readying of lifeboats and transmission of radio distress calls. The lifeboat process was slow and complex, made worse by limited training (a scheduled drill had just been canceled earlier that morning) and a lack of able seamen on the crew. Compounding the unfortunate situation, the Titanic‘s radio operators initially placed the ship at inaccurate coordinates in their outgoing calls. Tragically, the SS Californian was only miles away and could even see the stopped Titanic, but the Californian‘s radio operator had left his post for bed just 10 minutes before the collision. Later, when the Titanic discharged flares to signal any nearby ships, members of the Californian crew would remember seeing the white rockets, though their captain declined to take any action.

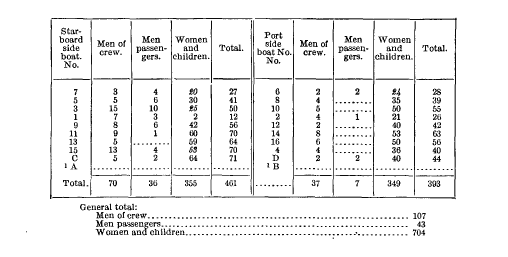

By 12:00 a.m., Titanic‘s 20 lifeboats were ready to be boarded, but even at full capacity, they only had space for 1,178 of the more than 2,200 passengers. As a result, Captain Smith ordered that women and children board first. Many refused, either out of fear of separating from their companions or because they thought they’d be safer on the giant vessel than in a small boat. Of the passengers who did board, the majority were from first and second class due to the disorganization (and in some cases, active circumvention) surrounding the transfer of third-class passengers to the lifeboat deck.

Even loading the passengers into the lifeboats did not go smoothly, with several suffering injuries or traumas from climbing off the ship, being jostled by other passengers, or being nearly flooded by the water coursing out of the ship’s side. A continued lack of communication only worsened the situation. At one point in the midst of the crisis, a Quartermaster even called the bridge to ask why he had just seen a lifeboat go past, oblivious of the emergency. Read this initial account of the lifeboat process.

At 12:45 a.m., the first lifeboat successfully rowed away from the Titanic with 28 passengers (though it could have held 65), and more followed gradually until the last left at 2:05 a.m.

The Ship’s Final Moments

As the lifeboats were being loaded, asymmetrical flooding into the lower decks gradually increased the Titanic‘s downward angle into the water. The ship’s electrical system failed at some point after 1:45 a.m., the time of the ship’s last clear transmission: “Engine room full up to boilers.”

At 2:15 a.m., the Titanic‘s downward angle began to increase much more rapidly, the movement causing a large “wave” to push back along the ship from the forward end which then swept many remaining passengers into the sea. The ship’s first funnel then collapsed, crushing several other passengers and causing another wave. As the weight of the water pushed the front of the ship down, the stern raised higher into the air, at one point reportedly reaching an angle of 45 degrees. Some passengers toward the stern were able to cling to the deck as it rose, but many others tumbled into the dark, freezing waves below.

Shortly after, the Titanic herself split in two, likely due to the extreme opposing forces on the bow and the stern. At 2:20 a.m., to the horror of those looking on from the lifeboats, the vessel disappeared from view entirely. Though survivors testified to a “great noise” and other evidence indicating the ship’s split, initial British and American investigations reported that she had sunk in one piece. However, the true nature of the Titanic‘s final moments was revealed when the wreck was found in 1985.

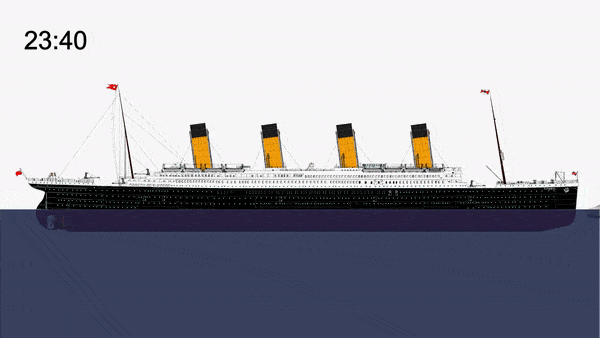

See a rendering of the entire sinking process below.

The hundreds of passengers and crewmembers that had managed to remain on board were thrown into the icy waters of the North Atlantic ocean, some injured or killed along the way by falling ship debris. Unfortunately, at 28 degrees Fahrenheit, it was impossible to survive in the water longer than ten or fifteen minutes.

Some lifeboats attempted to pull some of the swimmers aboard, but were forced to wait when it became clear that ship debris or overeager passengers could capsize their only hope of rescue. Those on the lifeboats sat by as their loved ones moaned in fear, agony, and anger, until the majority of them died or fell unconscious. At this point, Fifth Officer Harold Lowe gathered five of the lifeboats and began to look for survivors, finding only four alive (one of whom would die shortly after being rescued).

Rescue and Aftermath

After waiting for hours in the biting cold, the survivors were greeted by the arrival of the RMS Carpathia. One by one, they were unloaded from the lifeboats, treated, and those who could were left to reunite with their families and friends. As day began to break, it became apparent that the Titanic had been surrounded by gigantic fields of ice, dotted with hill-like icebergs. Two more ships answered the Titanic‘s distress calls by 9:15 a.m., at which point they began a search for any remaining survivors. There were, of course, none to be found. All in all, just over 700 out of the 2,200 total Titanic passengers were rescued by the Carpathia. The majority were first and second-class women and children.

Late in the day on April 19, RMS Carpathia arrived in New York City. The Titanic‘s passengers returned to land with relief but also outrage at the apparent negligence that led to the disaster. To learn more about the intricacies of the sinking, view a timeline of the disaster (later compiled by the British government).

Investigatory inquiries were launched in both Britain and the United States. Read their reports and find a transcript of U.S. hearings below:

- Report of British government on loss of steam ship Titanic

- Senate report on the Titanic disaster investigation

- Hearings on the Titanic disaster

The inquiries reported similar findings, including:

- The cause of the collision was the Titanic‘s high speed in a dangerous area.

- Lifeboat regulations of the time were woefully inadequate.

- The Titanic‘s captain was not negligent in his actions, but simply acting out of prior experience and known sailing standards. Similar actions in the future would henceforth be considered negligence.

- There was no negligence on the part of the White Star Line and Titanic builders.

- The captain of the SS Californian, though only miles away, ignored the Titanic‘s distress signals either out of “indifference or gross carelessness.”

View the entire list of recommendations from the British report and from the American report.

The disaster resulted in several changes in safety practices and maritime policy. In terms of lifeboats, both reports recommended that ships carry enough for those aboard, regularly inspect those boats, and mandate lifeboat training and drills. The receipt and acknowledgement of international distress signals was also a concern. In 1914, the first International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) convened to address many of these issues, ultimately incorporating several of the lifeboat recommendations and mandating that the firing of red rockets be used only as a sign for help (so as not to be misinterpreted).

In addition, the SOLAS treaty also led to the establishment of the International Ice Patrol, an internationally-funded agency of the United States Coast Guard dedicated to monitoring and reporting icebergs in the North Atlantic.

Shipbuilding after the sinking of the Titanic also changed, and many existing ships were refitted. The RMS Olympic, for example (a sister ship of the Titanic) received an extension to her double hull so that the bottom of the ship had increased protection above the waterline. Other ships saw increases to the height of their bulkheads so that separate compartments would remain completely watertight.

Finally, due to the tremendous loss of life that could have been avoided had the Californian operator been at his post, the United States government passed the Radio Act of 1912. The act mandated that radio communication on passenger ships be operated 24/7, and required a secondary power supply so that distress calls could not be missed.

Help Us Complete the Project

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us, please contact Shannon Hein at 716-882-2600 or shein@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give special thanks to the following libraries for their generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

- Wayne State University

- University of Utah

- UC Hastings

- University of Montana

- Law Library of Louisiana

- George Washington University

- University of Delaware

We will continue to need help from the library community to complete this project. Download this Excel file to see what we’re still missing.