On May 19, 2021, three survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre testified before a House Judiciary Subcommittee, recounting for the congressional record their memories of May 31 and June 1, 1921, when a white mob descended on the predominately Black neighborhood of Greenwood Avenue in Tulsa, OK, killing hundreds of Black people and leveling homes and businesses. The three survivors were all young children when the massacre occurred and are now all over one hundred years old. Through their testimony they urged Congress to act and give them and other survivors justice while they were still alive. Watch their testimony here.

The Tulsa Race Massacre, also known as the Tulsa Race Riot and the Black Wall Street Massacre, is one of the most devastating incidents of racial violence in American history, but one that, until recently, has largely been hidden from the general popular consciousness. However, its brutal depiction and central role in the hit 2019 HBO show Watchmen brought this piece of forgotten history to a wider audience, in an America currently re-evaluating its complex relationship with race. In April of 2021, the same House subcommittee that listened to survivors’ testimony advanced H.R. 40, the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act, a bill that establishes a 13-member commission to study the lingering effects of slavery and racial discrimination in the United States and the appropriateness of paying reparations to the descendants of enslaved Americans. On May 31, 2021, President Joe Biden visited the Greenwood neighborhood to mark the massacre’s centenary—the first sitting president to do so—and also proclaimed May 31, 2021 a day of national remembrance. Read the speech President Biden delivered in Tulsa here.

History can be hidden, but it can never be erased. Keep reading to bring the details into the light with HeinOnline.

Black Wall Street

Like many American cities in 1921, Tulsa was racially segregated. White and Black Tulsans rode in separate street cars, used separate washrooms, and even could not legally live on the same street. In Oklahoma and in the rest of the country, Black men were lynched with impunity. Through violence and intimidation, the Ku Klux Klan exerted incredible political and social influence throughout the state but especially in Tulsa, so much so that in 1923 Governor Jack Walton would declare martial law in the city—and then throughout the entire state—to try and rein in the Klan’s control over the courts.

In spite of the legal subjugation implemented by Jim Crow laws, Black Tulsans created a prosperous life for themselves. The city’s Greenwood District, formally organized in 1901, was a prosperous Black neighborhood where families owned their own homes and operated businesses, including five hotels, thirty-one restaurants, eight doctor’s offices, a movie theater, and grocery stores. This concentration of wealth and the success enjoyed by Greenwood’s residents led Greenwood to be known as “Black Wall Street.” It was considered to be the wealthiest Black community in the country.

The Dream Explodes

The exact particulars of what happened on May 30, 1921 are unknown. The historical record agrees on the broad strokes: Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old Black teenager, worked as a shoe shiner at the Tulsa Drexel Building. Needing to access the “colored only” bathroom upstairs, he boarded an elevator being operated by 17-year-old Sarah Page, who was white. Something may have happened during the elevator ride. Some sources say Rowland inadvertently stumbled while exiting the elevator, reflexively grabbing Page’s arm to halt his fall. Others say he accidentally stepped on her foot. Whatever precipitated it, Page slapped Rowland, and he ran from the building. But the rumor that swept through town was that Rowland had assaulted Page. The next day, an article appeared in the Tulsa Tribune bearing the headline “Nab Negro for Attacking White Girl in Elevator.” Rowland was arrested and held at the jail inside the Tulsa courthouse, but his arrest was insufficient to stop the violence that was to come. A white mob gathered outside the courthouse with the intent to lynch Rowland. A group of Black men, many of whom were World War I veterans, confronted them. There was a standoff between the two groups, with armed men in both camps. A shot of unknown origin was fired. It was the pretext needed for violence to erupt.

Local law enforcement deputized members of the white mob and gave them firearms. With this legal blessing, they swept through Greenwood, accompanied by the city’s police and the Oklahoma National Guard. Residents were shot in the streets and in their homes. Businesses and homes were looted and burned to the ground. A machine gun mounted to a truck fired upon the streets. Planes flew overhead, dropping turpentine bombs. Black men who were not killed were arrested en masse.

When the violence stopped sometime on June 1, Greenwood no longer existed. Forty-two square blocks—including 1,256 homes and virtually every business that had made up Greenwood—had been burned or razed. 8,000 Black residents were homeless and countless were arrested and interred in makeshift camps. Modern estimates put the value of property lost between $20 million and $200 million in today’s currency, and the death toll at 300 souls. Unmarked mass graves from the massacre are still being discovered today.

As the embers of destruction cooled, insurance companies systematically denied claims, citing riot exclusion clauses. The most famous of these cases was filed by William Redfearn, a white landlord who owned two businesses in Greenwood. His case, Redfearn v. American Central Insurance Company, ultimately went to the Oklahoma Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the insurance company. The rebuilding of Greenwood was further stopped by prohibitively expensive amendments to the Tulsa building code, passed just six days after the massacre. Traumatized and with no way to rebuild, thousands left Tulsa, never to return.

A Dream Deferred

A grand jury was convened in June of 1921 to investigate the cause of the riot. Their findings placed blame for the riot solely on the Black men who gathered outside the jail to protect Dick Rowland from being lynched; it absolved white participants from any wrongdoing. No one was ever criminally prosecuted for their part in the massacre. Hundreds of lawsuits were filed by residents along with millions of dollars of claims against the city; these too were all fruitless. In the years following the massacre, the state of Oklahoma actively worked to suppress discussion of what happened, with accounts of what took place in 1921 deliberately omitted from Oklahoma school textbooks, an omission that continued into the 21st century.

But as the new millennium approached, things slowly began to change. In 1997, the Oklahoma State Legislature authorized a commission to conduct a full-throated study of the massacre; their work took more than three years, culminating in a final report that acknowledged an active conspiracy on the part of the state to cover up the events of May 31 and June 1, 1921 and recommending that the state pay reparations to survivors and their descendants. Read the commission’s report here.

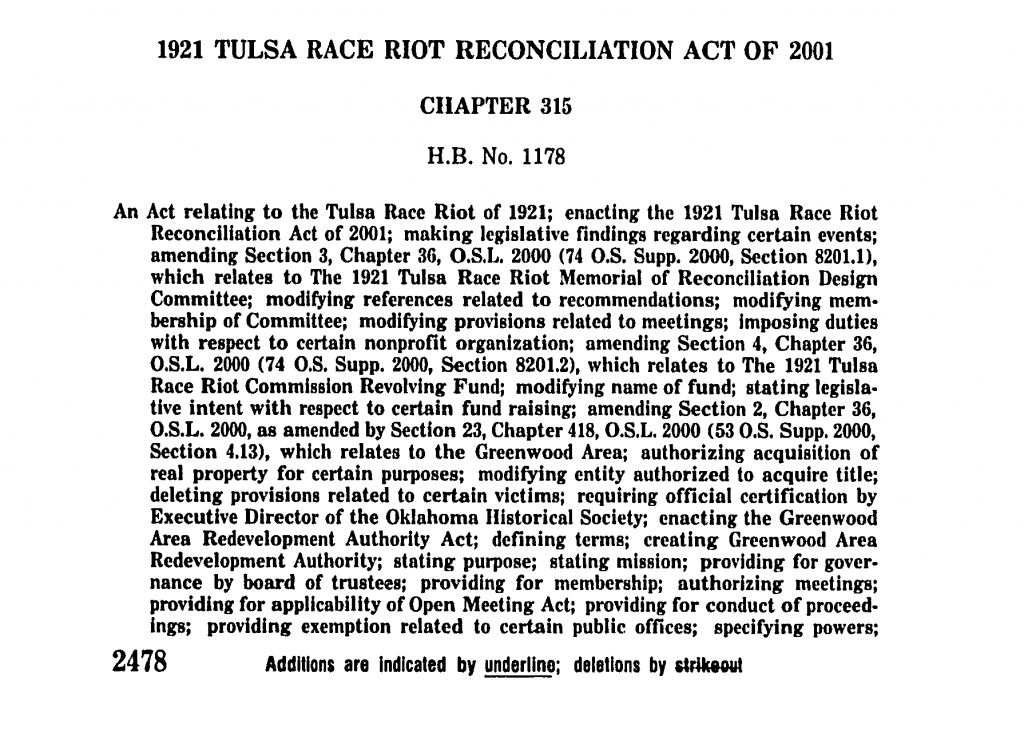

Following the report, Oklahoma passed the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act of 2001, which, among other things, created the Greenwood Area Development Authority, endowed a scholarship fund, and created a memorial to victims, which was dedicated in 2010. The Act also officially acknowledged that the massacre was not a “Negro uprising” as it had been previously categorized and that “there were moral responsibilities at the time of the riot which were ignored and has been ignored ever since rather than confront the realities of an Oklahoma history of race relations.” But the state stopped short of authorizing reparations as the commission’s final report had recommended.

Two years later, in 2003, a lawsuit was filed against the state of Oklahoma, the city of Tulsa, and the Tulsa police department on behalf of more than 200 survivors and their descendants. The case, Alexander v. State of Oklahoma, sought restitution for the massacre; both the federal district and appellate courts dismissed the suit on the basis that the statute of limitations for claims had passed. Although the case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, the Court denied to hear the case. In 2007, Congress held a hearing on H.R. 1995, which would have created a legal avenue for these claims to be heard in court, but the bill ultimately never passed. Survivors and descendants again filed suit against the city of Tulsa in 2020. The case is still pending.

As this post approaches the present day, the punctuation on the story of the Tulsa Race Massacre remains unwritten. It is unknown what, if anything, will come from the pending lawsuit or the survivors’ emotional testimony before Congress, and what, exactly, justice can look like after one hundred years. The debate over reparations—for Tulsa, for slavery—continues both in the United States and globally, as world leaders, state legislatures, and average people attempt to reckon with the past’s omnipresence.

The Power of Knowledge

As the aphorism goes, those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Don’t miss out on a good lesson: we love history at the HeinOnline blog and are always writing about new topics to inspire our users’ research and show off the wealth of knowledge contained in HeinOnline. Be sure to subscribe to the blog and never miss a post.