Niagara Falls is considered one of the great natural wonders of the world. Situated on the New York-Ontario border, Niagara Falls is made up of three separate waterfalls: the Horseshoe Falls (also known as the Canadian Falls), the American Falls, and the Bridal Veil Falls. Melting glaciers formed the Falls some 10,000 years ago about seven miles north of their present location, with the Falls retreating through erosion over the centuries by about 1 foot per year.[1]New York, a Guide to the Empire State, Compiled by Workers of the Writers’ Program (1940). This book is located in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. Today, Niagara Falls is a major tourist attraction, honeymoon destination, and an ecological reserve for protected species such as the lake sturgeon and bald eagle, with millions of visitors arriving each year from around the world to sail to the base of the Falls aboard the Maid of the Mist, stand on the Cave of the Winds hurricane deck, or Journey Behind the Falls. But Niagara Falls wasn’t always preserved for the public. Join us as we learn about one of America’s earliest conservation efforts: the movement to Free Niagara.

Chasing Waterfalls

The first recorded European visitor to gaze upon Niagara Falls was a French priest named Father Louis Hennepin,[2]New York, a Guide to the Empire State, Compiled by Workers of the Writers’ Program (1940). This book is located in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. who traveled with the French explorer La Salle[3]Thomas Falconer; Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. On the Discovery of the Mississippi, and on the South-Western, Oregon, and North-Western Boundary of the United States (1844). This book is located in HeinOnline’s … Continue reading on his expedition throughout the Great Lakes in the 1670s. La Salle and Hennepin arrived at Niagara Falls in December 1678, where Hennepin drew a sketch of the great cataract that was widely published some twenty years later. The French built forts to protect their interest in the Niagara River, including Fort Niagara[4]Merton M. Wilner. Niagara Frontier: A Narrative and Documentary History (1931). This book can be found in a forthcoming HeinOnline database, History of Buffalo. in 1726, and other settlers moved into the area, including farmer John Stedman, whose doomed goat herd spent the winter of 1779 on the island between the Bridal Veil and Horseshoe Falls, giving the land its name of Goat Island.[5]New York, a Guide to the Empire State, Compiled by Workers of the Writers’ Program (1940). This book is located in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library.

Mills had been built adjacent to and near the Falls since approximately 1805, when Augustus Porter [6]New York, a Guide to the Empire State, Compiled by Workers of the Writers’ Program (1940). This book is located in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. purchased from New York State a one-mile stretch of land immediately surrounding the Falls along with their adjoining water rights,[7]Gail E. H. Evans, Storm over Niagara: A Catalyst in Reshaping Government in the United States and Canada during the Progressive Era, 32 NAT. Resources J. 27 (1992). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. constructing a gristmill, saw mill, blacksmith’s shop, and tannery. The booming prosperity brought to the area by the completion of the Erie Canal[8]Laws of the State of New York, in Relation to the Erie and Champlain Canals, Together with the Annual Reports of the Canal Commissioners, and Other Documents Requisite for a Complete Official History of Those Works (1825). This book is located … Continue reading in 1825 and the Welland Canal[9]H.R. Rep. 201, 24th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1837). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. in 1836 saw more and more mills and factories built around the Falls. Tourism was increasing, as the canals moved not only cargo but people across the freshly interconnected state. Railroads[10]Gail E. H. Evans, Storm over Niagara: A Catalyst in Reshaping Government in the United States and Canada during the Progressive Era, 32 NAT. Resources J. 27 (1992). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. too were soon bringing more and more people to Niagara’s wonderous cataract: in the 1830s, a railroad between Buffalo and Lockport was completed, bringing tens of thousands of visitors each year, with the then-longest railway suspension bridge in the world being completed at the Falls in 1855. But all this progress came with a tradeoff. By the middle of the 19th century, the area surrounding the Falls was in the hands of private businessmen and was so developed that public access was severely limited. The flush of tourists arriving every year saw not the thundering Niagara, but mills, factories, fences, and hotels.

The Men on Goat Island

In August 1869, Frederick Law Olmsted[11]Frederick Law Olmstead Jr.; Kimball Theodora, Editors. Frederick Law Olmsted: Landscape Architect, 1822-1903 (1928). This book is located in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. arrived in Buffalo to design and build a system of parks for the city. Almost a decade prior, Olmstead and his partner Calvert Vaux had designed Manhattan’s Central Park, their first and possibly most well-known project. Now designing parks on the other side of New York State, Olmstead took a break from the city of Buffalo project to visit the American side of Niagara Falls. Joining him on the excursion were two prominent men: William Dorsheimer, the United States Attorney for the Northern District of New York, and architect Henry Hobson Richardson,[12]New York, a Guide to the Empire State, Compiled by Workers of the Writers’ Program (1940). This book is located in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. who would later work with Olmstead on the Buffalo Asylum. Olmstead was horrified by the extent of industrial development at the Falls, with Goat Island the only piece of land spared brickworks and smokestacks. High fences had been constructed around nearly every open sightline along the Niagara Gorge, through which visitors were charged for a peek at Niagara’s waters. Olmstead, Dorsheimer, and Richardson felt compelled to act. They wanted to free Niagara from the industrial blight that had encircled her.

The men had good reason to believe there would be widespread public support for their cause. Just a few years prior, in 1857, one painting had taken the country by storm. It was the latest work from landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church, depicting a panoramic view of the top of the Horseshoe Falls. Church’s painting, Niagara, was a giant, both in its reception and its physical dimensions. Painted on a canvas that measures 3 feet high and over 7 feet long, Niagara attracted 100,000 visitors[13]Gail E. H. Evans, Storm over Niagara: A Catalyst in Reshaping Government in the United States and Canada during the Progressive Era, 32 NAT. Resources J. 27 (1992). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. during its one-month exhibition in Manhattan before embarking on an equally successful exhibition tour around Europe. Clearly, even in oil on canvas, Niagara Falls held a great power over a captive audience.

Back in the states, a small group of conservationists, including Olmstead, began crusading for the land around the Falls to be cleared of the mills and factories that had been constructed up and down the Niagara Gorge, returning the Falls to their natural, unspoiled state. Known as the Free Niagara conservationists, the movement attracted some prominent supporters, including Charles Darwin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and John Ruskin. New York State Assemblyman Thomas Vincent Welch was the movement’s most ardent supporter in the New York State Assembly. Yet various efforts to create an international park at the Falls[14]Gail E. H. Evans, Storm over Niagara: A Catalyst in Reshaping Government in the United States and Canada during the Progressive Era, 32 NAT. Resources J. 27 (1992). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. were met with enthusiasm that never manifested legislation.

In the early 1880s, a group of approximately 300 private citizens formed the Niagara Falls Association and began turning the political screws to make the park at the Falls a reality. Shortly after the Association’s formation, the Free Niagara movement finally began to gain some real legal traction when future President of the United States Grover Cleveland[15]Francis J. Walter, Grover Cleveland and Buffalo. This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. became New York State governor in 1883. Cleveland was a friend of William Dorsheimer, one of the men who had toured Goat Island with Frederick Law Olmstead back in 1869. With the governor’s ear, on April 30, 1883, “An act to authorize the selection, location, and appropriation of certain lands in the village of Niagara Falls for a state reservation and to preserve the scenery of the falls of Niagara”[16]1883 N.Y. Laws 503. This act is found in HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. was signed, establishing the first state park in America, the Niagara Reservation. Assemblyman Welch was named the first superintendent of the park. Two years later, the Ontario provincial government passed its own legislation creating Queen Victoria Niagara Falls Park. Both park commissions worked together over the coming years to buy the private land that now fell within the boundaries of the new Niagara Falls park, razing hotels and factories to restore the land to its natural beauty. The movement inspired by Olmstead’s visit had achieved its grand ambition: Niagara Falls was free.

Electric Treaties

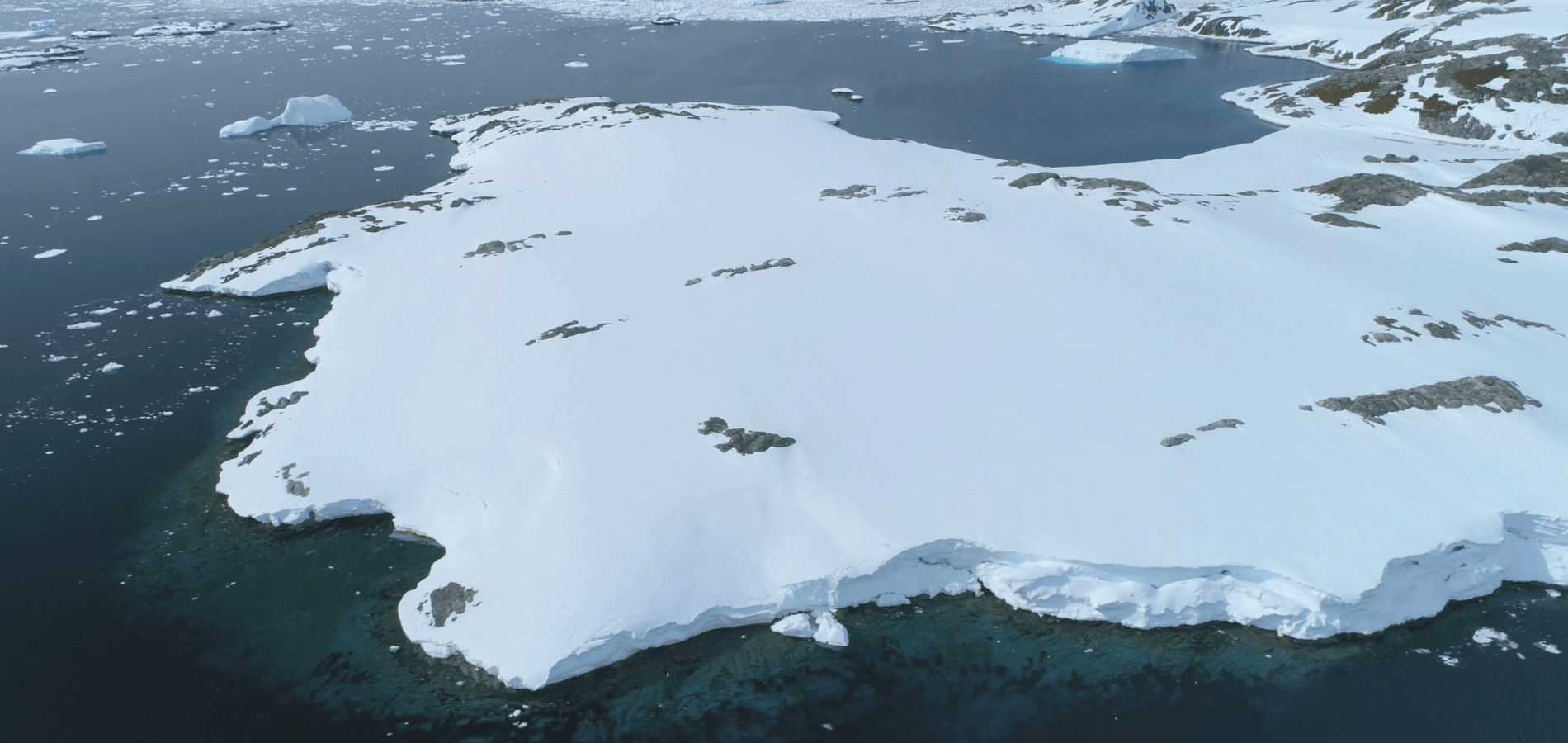

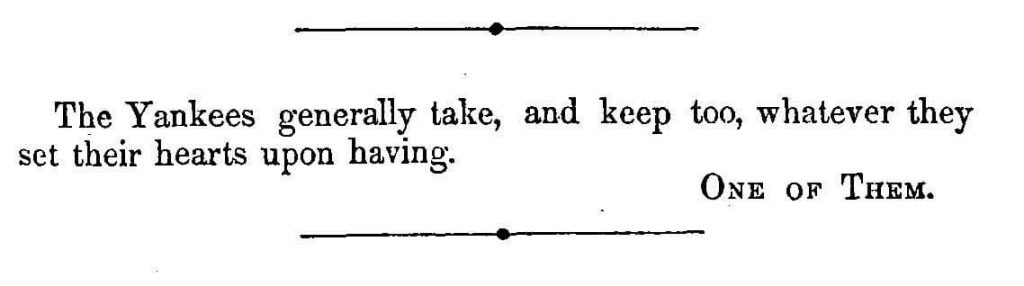

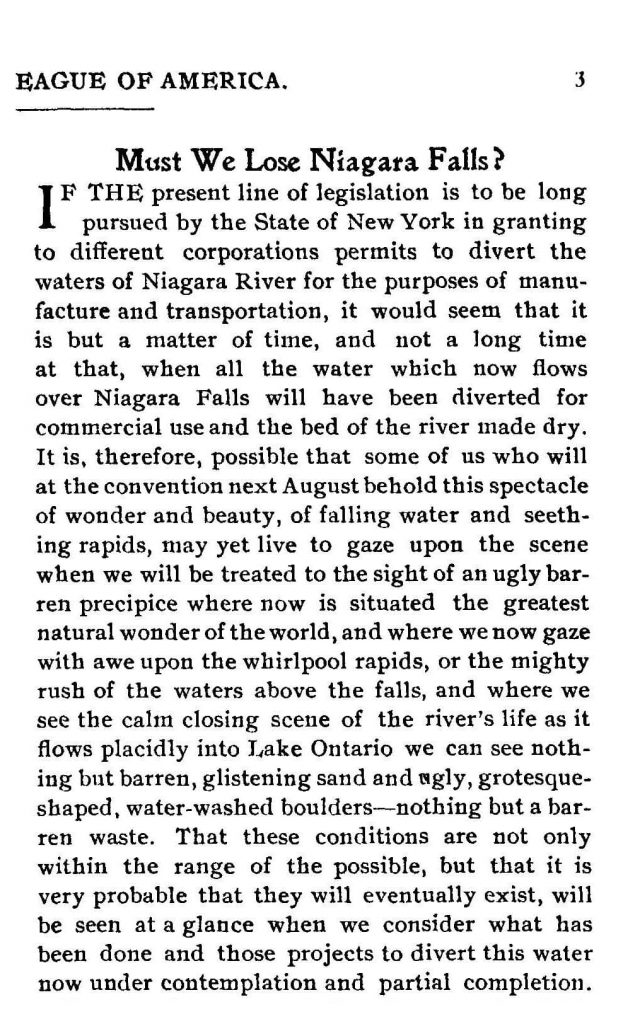

But it was not guaranteed the Falls would stay that way. Even as the park commissioners set about restoring the land, private interests began looking to capture Niagara Falls for hydroelectric power. Within three years of “freeing” Niagara Falls, New York State and the Queen Victoria Park Commission began granting charters to various hydroelectric companies to divert water from the Niagara River; by 1905, power plants were being built on land within the Niagara Reserve, dynamiting through limestone to build power stations atop and at the base of the Falls. The rate at which power plants were being built and water diverted away from the Falls to feed a nation hungry for electricity created a very real fear that without regulation the Falls would run dry. One contemporary estimate from the time figured that 22% of the river’s water had already been diverted from the Falls. “Unless another strenuous effort is made,” one commentator wrote, “Niagara Falls will become a relic of an age which was too stupid to understand their value.”[17]10 BULL. COM. L. LEAGUE AM. 4 (1905). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

Attempts by the Niagara Falls Reserve Commission to pressure New York State to stop granting charters to hydroelectric companies had mixed results. The Commission convinced the state to stop allowing new water diversions in 1894, but failed to succeed in getting a state constitutional amendment[18]William H. Steele, Reviser. Revised Record of the Constitutional Convention of the State of New York, May 8, 1894 to September 29, 1894 (1900). This book is located in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. that would have prohibited all water diversions above the Falls.

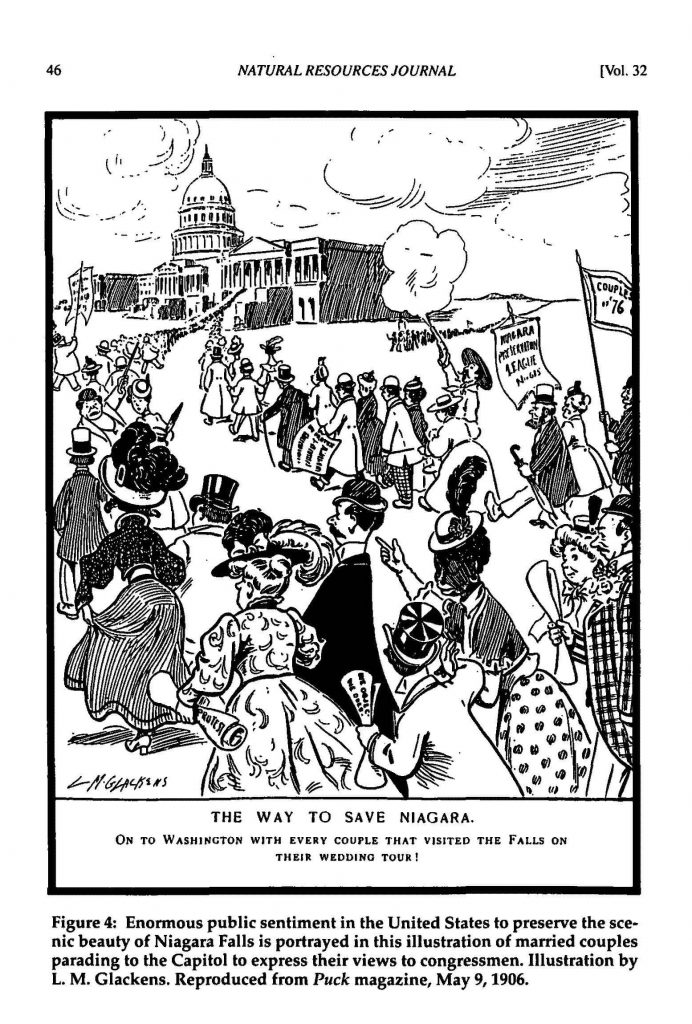

Recognizing that federal involvement would be needed to ensure the long-term protection of Niagara Falls, the Niagara Falls Reservation Commission began pressuring Congress to intervene. Their efforts resulted in the 1902 Rivers and Harbors Act,[19]32 Stat. 331 (1902). This act is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. which created the International Waterways Commission. The International Waterways Commission included American and Canadian representatives charged with investigating problems in boundary waters between the two countries, including Niagara Falls. In its 1906 report, the Commission warned[20]S. Doc. 242, 59th Cong., 1st Sess. (1906). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. that the total quantity of water currently authorized to be diverted out of the Niagara River was more than double the current water volume passing over the American side of the Falls. Editorials roused public indignation over Niagara Falls being pillaged to line the pockets of greedy capitalists, and petitions [21]Gail E. H. Evans, Storm over Niagara: A Catalyst in Reshaping Government in the United States and Canada during the Progressive Era, 32 NAT. Resources J. 27 (1992). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. bombarded both the White House and the office of the Canadian Governor General.

The Commission’s ideal proposed solution was an international treaty[22]S. Rep. 1611, 59th Cong., 1st Sess. (1906). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. between the United States, Great Britain, and Canada. The resulting 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty[23]36 Stat. 2448 (1909). This act is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. set limits on how much water the United States and Canada were able to divert from Niagara Falls, with the United States nearly hitting its allocated amount by 1918.[24]Diversion of Water from the Niagara River: Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Sixty-fifth Congress, Second Session on H.R. 11891, Statement of Brig. Gen. Charles Keller, Engineer Corps U.S.A. June 7, … Continue reading The 1950 Niagara Treaty[25]1 U.S.T 694. This treaty is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Treaties and Agreements Library. set new water diversion regulations, which are administered by the International Niagara Board of Control. Today, water flow over Niagara Falls varies depending on the time of year (tourist season vs. off-season) and time of day, with a lower water flow at night compared to daytime. Water flow is controlled by the International Control Dam on the Canadian side of the Niagara River.

Hydroelectric power[26]Development of Power at Niagara Falls, N.Y. Hearings before a Subcommittee on Public Works, United States Senate, Eighty-fifth Congress, First Session on S. 512 and S. 1037, Bills to Authorize the Construction of Certain Works of Improvement in the … Continue reading continues to be generated from Niagara Falls today. The Schoellkopf Power Station[27]H.R. Rep. 862, 85th Cong., 1st Sess. (1957). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. generated power from the Falls from approximately 1882 until the station’s collapse in 1956; visitors to the Falls today pass by the ruins of the station as they board the Maid of the Mist. The Schoellkopf Power Station was replaced by the Robert Moses Niagara Power Plant, which opened in 1961 and is still in operation today.

Powering Research, Electrifying History

You can free your research with the HeinOnline Blog, which contains tips and tricks, news on all of HeinOnline’s new features, and posts just like this illuminating the natural wonders (of research) contained within the millions of digitized pages in HeinOnline. Make sure you never miss a post by subscribing to the blog and receive every new post directly to your inbox.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1, ↑2, ↑5, ↑6, ↑12 | New York, a Guide to the Empire State, Compiled by Workers of the Writers’ Program (1940). This book is located in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑3 | Thomas Falconer; Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. On the Discovery of the Mississippi, and on the South-Western, Oregon, and North-Western Boundary of the United States (1844). This book is located in HeinOnline’s Prestatehood Legal Materials database. |

| ↑4 | Merton M. Wilner. Niagara Frontier: A Narrative and Documentary History (1931). This book can be found in a forthcoming HeinOnline database, History of Buffalo. |

| ↑7, ↑10, ↑13, ↑21 | Gail E. H. Evans, Storm over Niagara: A Catalyst in Reshaping Government in the United States and Canada during the Progressive Era, 32 NAT. Resources J. 27 (1992). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑8 | Laws of the State of New York, in Relation to the Erie and Champlain Canals, Together with the Annual Reports of the Canal Commissioners, and Other Documents Requisite for a Complete Official History of Those Works (1825). This book is located in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. |

| ↑9 | H.R. Rep. 201, 24th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1837). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑11 | Frederick Law Olmstead Jr.; Kimball Theodora, Editors. Frederick Law Olmsted: Landscape Architect, 1822-1903 (1928). This book is located in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. |

| ↑14 | Gail E. H. Evans, Storm over Niagara: A Catalyst in Reshaping Government in the United States and Canada during the Progressive Era, 32 NAT. Resources J. 27 (1992). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑15 | Francis J. Walter, Grover Cleveland and Buffalo. This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑16 | 1883 N.Y. Laws 503. This act is found in HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. |

| ↑17 | 10 BULL. COM. L. LEAGUE AM. 4 (1905). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑18 | William H. Steele, Reviser. Revised Record of the Constitutional Convention of the State of New York, May 8, 1894 to September 29, 1894 (1900). This book is located in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. |

| ↑19 | 32 Stat. 331 (1902). This act is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑20 | S. Doc. 242, 59th Cong., 1st Sess. (1906). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑22 | S. Rep. 1611, 59th Cong., 1st Sess. (1906). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑23 | 36 Stat. 2448 (1909). This act is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑24 | Diversion of Water from the Niagara River: Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Sixty-fifth Congress, Second Session on H.R. 11891, Statement of Brig. Gen. Charles Keller, Engineer Corps U.S.A. June 7, 1918 (1918). This hearing can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑25 | 1 U.S.T 694. This treaty is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Treaties and Agreements Library. |

| ↑26 | Development of Power at Niagara Falls, N.Y. Hearings before a Subcommittee on Public Works, United States Senate, Eighty-fifth Congress, First Session on S. 512 and S. 1037, Bills to Authorize the Construction of Certain Works of Improvement in the Niagara River for Power and Other Purposes (1957). This hearing can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑27 | H.R. Rep. 862, 85th Cong., 1st Sess. (1957). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |