Detective-Inspector Arthur Neil knew the deaths were not accidental. He just didn’t have any proof.

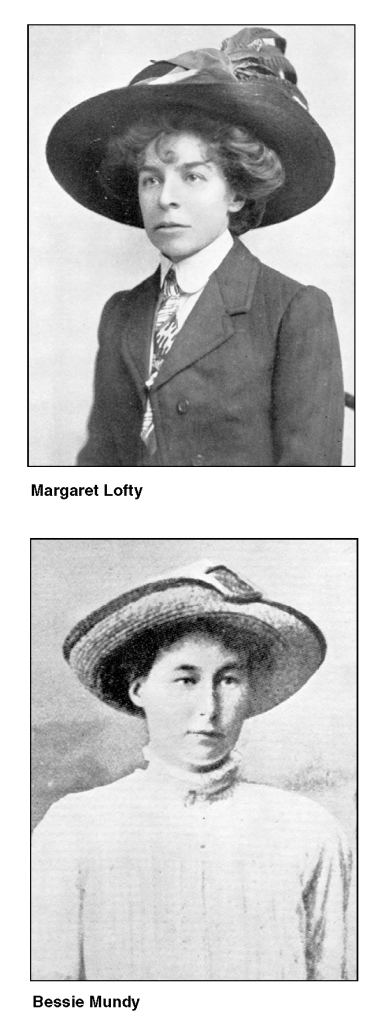

It started with a letter on his desk at Scotland Yard. The letter was from Joseph Crossley, a landlord from Blackpool, and it contained two newspaper clippings. The first was an article from the News of the World about the death of newly married Margaret Lofty, on December 18, 1914. Margaret had been found drowned in her bathtub the day after her wedding to John Lloyd.

The second clipping concerned a coroner’s inquest into the death of Alice Burnham in 1913. Alice had been found by her husband, George Smith, drowned in the bathtub the previous December. Crossley owned the lodging house where Alice had died.[1]Douglas G. Browne and E.V. Tullett. Scalpel of Scotland Yard: The Life of Sir Bernard Spilsbury (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. Both he and Alice’s father had seen the report of Margaret Lofty’s death and immediately noticed the similarities between Alice’s death in Blackpool and Margaret’s in London. They believed the two incidents were somehow connected.

Intrigued, D.I. Neil started digging. The responding officer had found Alice’s husband none too bereaved at his wife’s sudden death. Next, Neil visited the rented rooms where the Smiths had been staying to see the bathtub where Alice had drowned. “If anyone can get drowned in a bath like this,” Neil thought, looking at the small tub, “it’s a marvel.”[2]Arthur Fowler Neil. Man-Hunters of Scotland Yard: The Recollections of Forty Years of a Detective’s Life (1933). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Criminal Justice & Criminology collection.

But how was he going to prove Alice had been murdered? And what was the connection between George Smith and John Lloyd?

Suspicious Circumstances

Originally, the coroner had ruled Alice Burnham’s and Margaret Lofty’s deaths accidental, officially termed “death by misadventure.”[3]Arthur Lambton. Thou Shalt Do No Murder (1930). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. Both husbands reported their wives had felt unwell in the hours before their deaths. But the more D.I. Neil looked, the more suspicious Margaret Lofty’s death seemed.

Facts of Margaret’s Case

- She and John had only been married for one day when she died.

- John Lloyd had originally planned to rent a room at a different boarding house but had complained to the landlady about the size of its bathtub.[4]Arthur Fowler Neil. Man-Hunters of Scotland Yard: The Recollections of Forty Years of a Detective’s Life (1933). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Criminal Justice & Criminology collection.

- When Lloyd went to check out the lodging house on Bismark Road where Margaret later died, his first question had been if their room had a bathtub[5]Arthur Fowler Neil. Man-Hunters of Scotland Yard: The Recollections of Forty Years of a Detective’s Life (1933). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Criminal Justice & Criminology collection.

- Hours before Margaret’s death, she had withdrawn all her savings from the bank and drafted a will making John her sole beneficiary.[6]Arthur Fowler Neil. Man-Hunters of Scotland Yard: The Recollections of Forty Years of a Detective’s Life (1933). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Criminal Justice & Criminology collection.

- Margaret’s undertaker reported that John Lloyd had complained about the price of her burial and bought the cheapest coffin[7]Arthur Fowler Neil. Man-Hunters of Scotland Yard: The Recollections of Forty Years of a Detective’s Life (1933). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Criminal Justice & Criminology collection. available.

- Two weeks before her death, John Lloyd took out a life insurance policy on Margaret for £700,[8]Arthur Lambton. Thou Shalt Do No Murder (1930). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. about £56,000 ($63,000) in today’s money.

Facts of Alice’s Case

Money also seemed to be a motive in Alice Burnham’s death. Two months before her death, George Smith had taken out a life insurance policy on her for £500[9]Eustace Jervis. Twenty-Five Years in Six Prisons (1925). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Criminal Justice & Criminology collection. or about £40,000 ($45,000) in today’s money. He had also been similarly unmoved by his new bride’s sudden death, telling landlord Joseph Crossley, “When they’re dead, they’re dead,”[10]Douglas G. Browne and E.V. Tullett. Scalpel of Scotland Yard: The Life of Sir Bernard Spilsbury (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. and buried her in a common grave.

Neil Catches His Man

On February 1, 1915, D.I. Neil found the elusive John Lloyd—on his way to collect his insurance payout from Margaret’s death. Lloyd confessed that his real name was George Joseph Smith, and that he was the same George Smith who married Alice Burnham. But Smith maintained he was only a very unlucky widower, not a murderer. Neil arrested George Smith on the charge of “making a false entry of marriage,”[11]Arthur Fowler Neil. Man-Hunters of Scotland Yard: The Recollections of Forty Years of a Detective’s Life (1933). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Criminal Justice & Criminology collection. for using a false name—John Lloyd—when he married Margaret.

George Smith was now in custody. But D.I. Neil still needed proof that Smith’s crimes went beyond marital fraud. He was hoping to now find it; Margaret Lofty was exhumed[12]Arthur Fowler Neil. Man-Hunters of Scotland Yard: The Recollections of Forty Years of a Detective’s Life (1933). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Criminal Justice & Criminology collection. for another autopsy. D.I. Neil’s current theory was that Alice and Margaret were poisoned, not drowned, and then staged in the bathtubs. He needed the best pathologist, the foremost medico-detective England had, to examine the bodies. He needed a real-life Sherlock Holmes.

Spilsbury Enters the Case

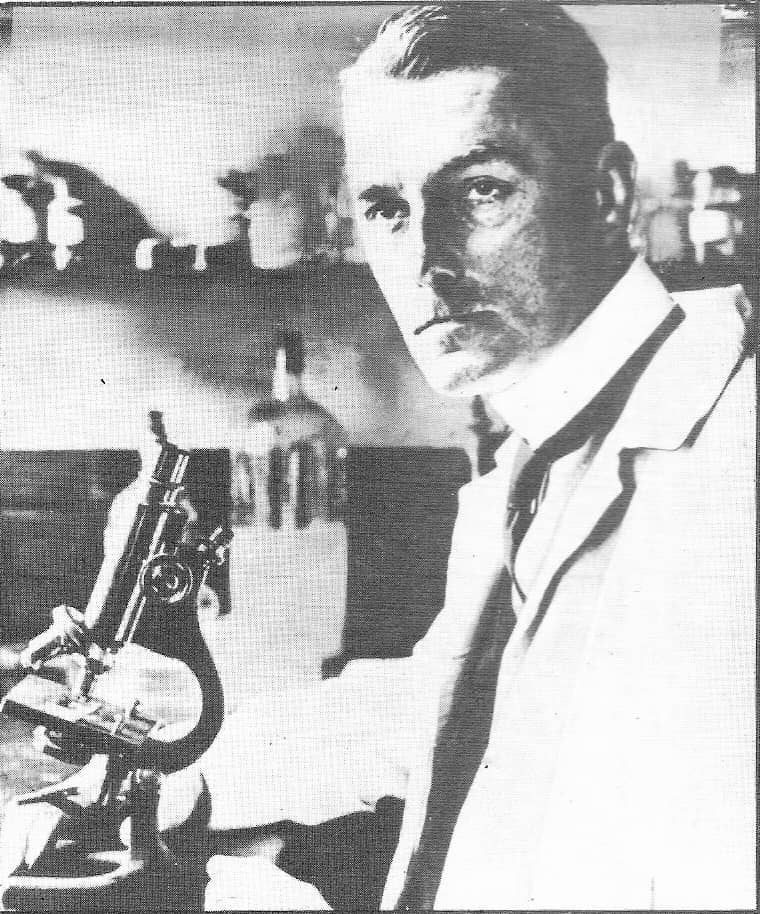

Bernard Spilsbury didn’t live with his biographer on Baker Street, but he was the closest Scotland Yard had to the mythical detective. Spilsbury had begun earning a reputation as his country’s preeminent pathologist after his testimony in the sensational Hawley Harvey Crippen case[13]Filson Young, Editor. Trial of Hawley Harvey Crippen (1920). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. five years earlier, in 1910. In that case, he had produced the one forensic link between Crippen and his victim.

Margaret Lofty and Alice Burnham were exhumed. Both women appeared to have been perfectly healthy at the time of their deaths. But Spilsbury could find no evidence that either woman had been poisoned. Margaret Lofty had superficial bruises on her left arm[14]Douglas G. Browne and E.V. Tullett. Scalpel of Scotland Yard: The Life of Sir Bernard Spilsbury (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. but other than that there was no evidence that her or Alice’s deaths were anything but an unhappy accident. The two bathtubs were moved to London for Spilsbury to examine.

Exposing a Criminal’s Dark Past

D.I. Neil’s investigation was dragging the real George Smith into the light. Sent to a reformatory at the age of nine,[15]Herbert Arthur. All the Sinners (1931). This book is found in HeinOnline’s History of Capital Punishment. he repeatedly returned to prison throughout his adolescence for theft and larceny[16]Herbert Arthur. All the Sinners (1931). This book is found in HeinOnline’s History of Capital Punishment. before apparently settling down, opening a bakery shop in Leicester and marrying Catherine Thornhill in 1898.[17]Arthur Lambton. Thou Shalt Do No Murder (1930). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials.

Smith sent his wife to work as a maid, forcing her to steal from her employers.[18]Ernest Bowen-Rowlands. In the Light of the Law (1931). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. When she was caught, Catherine turned in her husband, who was sentenced to two years’ hard labor.[19]Arthur Lambton. Thou Shalt Do No Murder (1930). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. Out of prison, George Smith began the next phase of his criminal career.

George Smith’s Life of Bigamy

- In 1899, while still married to Catherine Thornhill, George Smith used a false name to marry another woman in London. He disappeared after clearing out her savings.

- In June 1908, using a false name, George Smith married wealthy widow Florence Wilson, abandoning her within a month after clearing out all her savings.

- In July 1908, using his real name, George Smith married Edith Pegler in Brighton.

- On October 29, 1909, using the name George Rose, he married Sarah Freeman. Six days after their wedding, he took all her money and left, returning to Edith Pegler for a short time.

- On August 26, 1910, George Smith married Beatrice “Bessie” Mundy, this time using the name Henry Williams. Bessie had a not insignificant inheritance held in a trust. Unable to gain access to this money, Smith took what little she had and left.

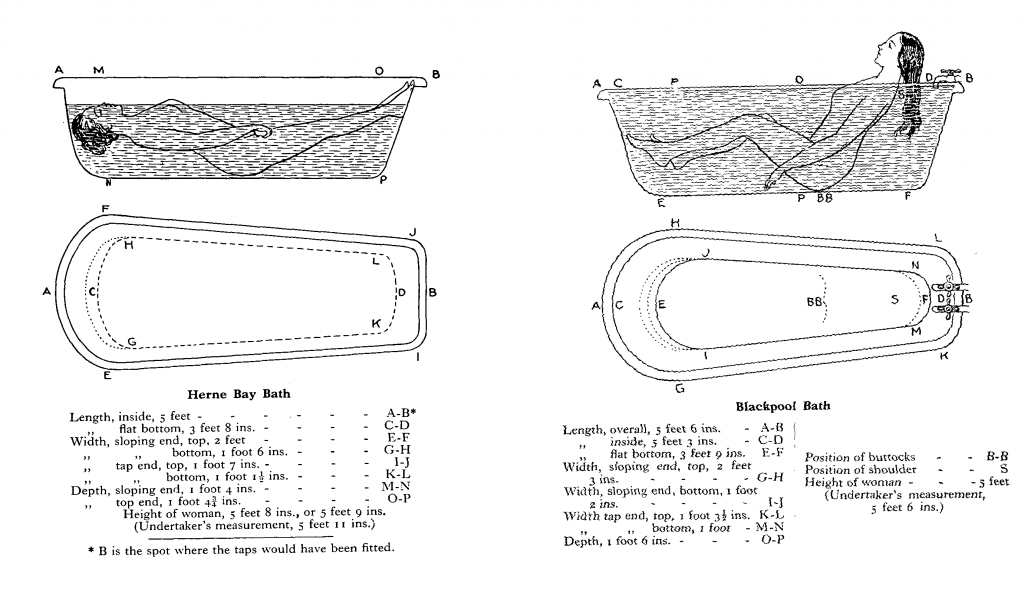

- George later returned to Bessie, and in May 1912 they took rooms together in Herne Bay. On July 8, 1912, Bessie made her will, leaving her “husband” her modest fortune of £2,000 (or about £160,000/$180,000 today).

- The next day, July 9, George Smith bought a bathtub for their Herne Bay rooms.

- On July 13, 1912, Bessie Mundy died while taking a bath.

Once D.I. Neil and Spilsbury learned about Bessie Mundy, they had her exhumed, too. On her skin Spilsbury found goosebumps, which happens, he told D.I. Neil, “in some cases of sudden death, and perhaps more frequently in sudden death from drowning.”[20]Douglas G. Browne and E.V. Tullett. Scalpel of Scotland Yard: The Life of Sir Bernard Spilsbury (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. The tub that Bessie died in was tracked down and also brought to London for examination.

The Brides in the Bath

But if Smith hadn’t drugged any of his wives, and without any sign pointing to a struggle, how had he killed them? Bessie Mundy was 5’7″ and her bathtub was only 5′ long.[21]Douglas G. Browne and E.V. Tullett. Scalpel of Scotland Yard: The Life of Sir Bernard Spilsbury (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. She had been found in death still holding a bar of soap.[22]Eric R. Watson, Editor. Trial of George Joseph Smith (1949). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. All three women had been found on their backs, with their legs straight, completely submerged. The tubs each tapered to a narrow end, containing only about one foot of water.

Crouched in the narrow bath, if any of the women did have a seizure, Spilsbury could not see how they could have drowned and ended up in the positions they were found in; they would have collapsed face downwards,[23]Eric R. Watson, Editor. Trial of George Joseph Smith (1949). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. not slid backwards, surely striking their face on some part of the bath. The women were all too big and the tubs far too small. For Spilsbury, the math did not add up.

Elementary, My Dear Spilsbury

George Joseph Smith’s trial for the murder of Bessie Mundy started on June 22, 1915. The three bathtubs were brought into the courtroom as exhibits. One spectator allegedly sat in one of the small tubs and got stuck.[24]Arthur Lambton. Thou Shalt Do No Murder (1930). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials.

In a blow to the defense, the judge allowed testimony on Alice Burnham’s and Margaret Lofty’s deaths to be given, to show, as the judge phrased it, “whether he [Smith] had a system of murdering.”[25]Eric R. Watson, Editor. Trial of George Joseph Smith (1949). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. It was one of the earliest instances that ‘system’ was allowed in a murder trial.

Bernard Spilsbury took the stand on the trial’s sixth day. He testified that all three women had died when, in the bath, their guard down, George Smith had grabbed them by the ankles and swiftly pulled them under water.[26]Eric R. Watson, Editor. Trial of George Joseph Smith (1949). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. Water rushed up the nose and into the mouth. Legs held in the air, their heads completely submerged, the women would be helpless to defend themselves, sent into shock by the sudden intake of water. They lost consciousness in a matter of minutes and died.

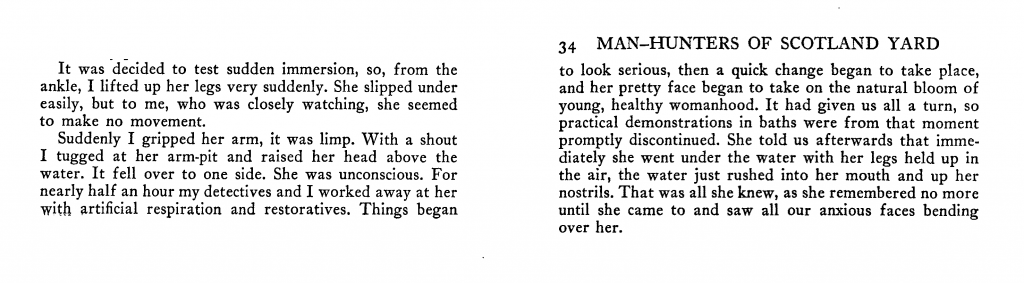

Spilsbury knew his theory was possible because of a very unorthodox experiment. D.I. Neil had filled one of the baths with water and had a female swimmer (in a bathing suit, of course), sit in it. With the prosecuting attorney watching, Neil suddenly grabbed the woman’s ankles and submerged her under water, to immediate and horrific effect, as detailed in Neil’s memoir, extracted below:

George Joseph Smith was found guilty of the murder of Bessie Mundy on July 1, 1915 and hanged on August 13, 1915.

Their Last Bow

Bernard Spilsbury

The case of the “Brides in the Bath,” as it was dubbed by the press, cemented Bernard Spilsbury’s reputation as Britain’s greatest pathologist, and today he is considered to be the father of forensics. In 1934, Time magazine christened Spilsbury “the living successor to mythical Sherlock Holmes.”[27]Andrew Rose, Lethal Witness, 77 MEDICO-LEGAL J. 93 (2009). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. He was knighted in 1923 and for the remainder of his life was esteemed as “one of the most distinguished figures in forensic medicine.”[28]Douglas G. Browne and E.V. Tullett. Scalpel of Scotland Yard: The Life of Sir Bernard Spilsbury (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf.

Several articles Spilsbury wrote for the Medico-Legal and Criminological Review and the Transactions of the Medico-Legal Society, which Spilsbury served as the president of from 1933 until 1947, can be accessed on Bernard Spilsbury’s Author Profile Page. Spilsbury committed suicide in 1947 at the age of 70.

Spilsbury’s reputation, so ironclad in his lifetime, has weakened in the eyes of history. He abhorred working with others on cases and was loathe to ever change his opinion, even if facts later proved he was wrong. Spilsbury’s belief in his own infallibility,[29]Keith Simpson, Sir Bernard Spilsbury, 29 MEDICO-LEGAL J. 182 (1961). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. combined with the public’s worshipful trust in him, made him an impossible witness to overcome in the courtroom. His testimony almost certainly helped convict some innocent men.[30]Andrew Rose, Lethal Witness, 77 MEDICO-LEGAL J. 93 (2009). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

Arthur Neil

Detective-Inspector Arthur Neil became one of the most famous detectives at Scotland Yard in the early 20th century, joining a group of esteemed detectives known colloquially as the Big Five. Joining the Metropolitan Police in 1888, he served for forty years, retiring in 1928. His memoirs,[31]Arthur Fowler Neil. Man-Hunters of Scotland Yard: The Recollections of Forty Years of a Detective’s Life (1933). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Criminal Justice & Criminology collection. found in HeinOnline, are heavily cited throughout this post.

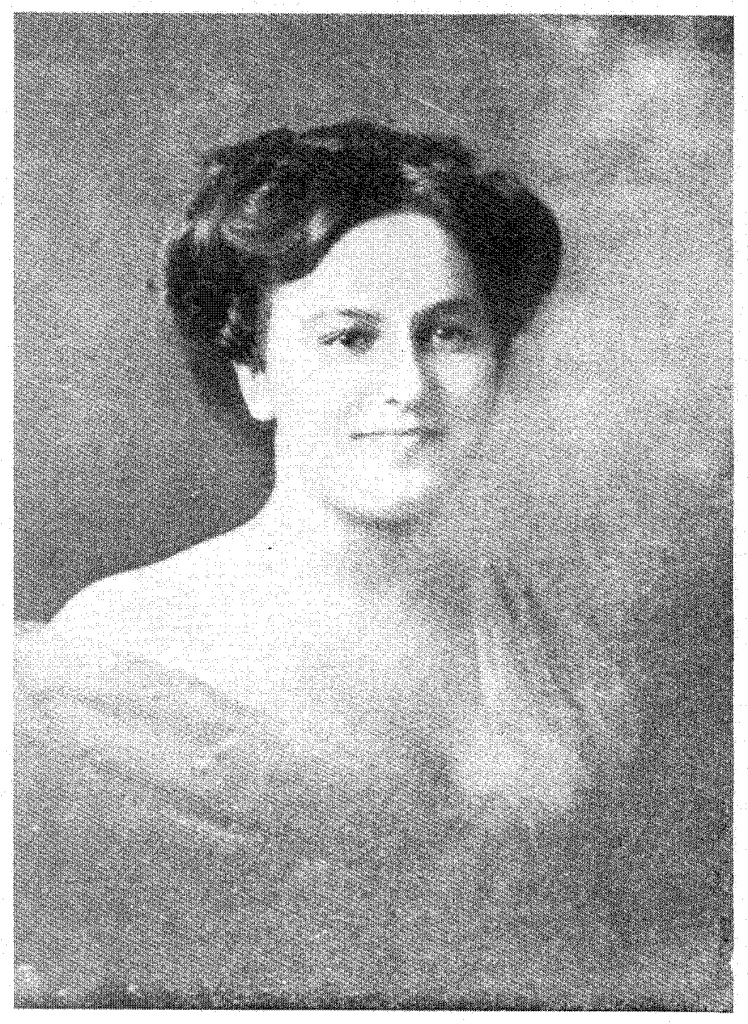

Edith Pegler

As for poor Edith Pegler, she was the only one of George Smith’s many brides who he married in his real name. Smith probably genuinely cared for her in some twisted way. He wrote her a letter days before his execution.[32]Eric R. Watson, Editor. Trial of George Joseph Smith (1949). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials.

Smith flitted in and out of her life, disappearing for months on end, returning to her for a few weeks in between his other marriages, flush with cash. He explained his absences by claiming he was traveling for business. The two moved around England constantly throughout their marriage. For a time, Edith and George ran an antiques shop on Bath Road[33]Eric R. Watson, Editor. Trial of George Joseph Smith (1949). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. (yes, really) in Bristol.

Edith testified for the prosecution at George’s trial. In addition to recounting her lonely, nomadic life, she was questioned extensively about the baths in their many homes and apartments, and whether her husband was given to often altering his appearance or bathing frequently.[34]Eric R. Watson, Editor. Trial of George Joseph Smith (1949). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials.

In a statement to the police, Edith said,[35]Eric R. Watson, Editor. Trial of George Joseph Smith (1949). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials.

Just after Christmas, 1914, we were living in apartments at 10 Kennington Avenue, Bristol, and I said I was going to have a bath. He said—”In that bath there (referring to the bathroom)? I should advise you to be careful of those things, as it is known that women have often lost their lives through weak hearts and fainting in the bath.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1, ↑10, ↑14, ↑20, ↑21, ↑28 | Douglas G. Browne and E.V. Tullett. Scalpel of Scotland Yard: The Life of Sir Bernard Spilsbury (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑4, ↑5, ↑6, ↑7, ↑11, ↑12, ↑31 | Arthur Fowler Neil. Man-Hunters of Scotland Yard: The Recollections of Forty Years of a Detective’s Life (1933). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Criminal Justice & Criminology collection. |

| ↑3, ↑8, ↑17, ↑19, ↑24 | Arthur Lambton. Thou Shalt Do No Murder (1930). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. |

| ↑9 | Eustace Jervis. Twenty-Five Years in Six Prisons (1925). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Criminal Justice & Criminology collection. |

| ↑13 | Filson Young, Editor. Trial of Hawley Harvey Crippen (1920). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. |

| ↑15, ↑16 | Herbert Arthur. All the Sinners (1931). This book is found in HeinOnline’s History of Capital Punishment. |

| ↑18 | Ernest Bowen-Rowlands. In the Light of the Law (1931). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. |

| ↑22, ↑23, ↑25, ↑26, ↑32, ↑33, ↑34, ↑35 | Eric R. Watson, Editor. Trial of George Joseph Smith (1949). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. |

| ↑27, ↑30 | Andrew Rose, Lethal Witness, 77 MEDICO-LEGAL J. 93 (2009). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑29 | Keith Simpson, Sir Bernard Spilsbury, 29 MEDICO-LEGAL J. 182 (1961). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |