On February 3, 2023, a Norfolk Southern train carrying hazardous materials derailed in East Palestine, Ohio. Fearing the derailed cars would explode, first responders preemptively burned its toxic cargo—vinyl chloride, a known carcinogen. Five thousand residents were evacuated from the surrounding area. On February 8, residents were allowed to return to their homes but continue to demand answers on any long-term health effects caused by the derailment. On March 14, the state of Ohio sued Norfolk Southern to make sure the railroad company pays for both the current environmental cleanup and for years of groundwater and soil monitoring.

The East Palestine tragedy has brought heightened attention to the railroad industry, the role of the EPA, and what duty companies have to communities impacted by their actions. In today’s post, we are exploring one of the worst environmental disasters in American history, when another rustbelt community was exposed to toxic chemicals—the Love Canal disaster.

William Love’s Canal

In 1892, William T. Love[1]Theodore Baurer, Love Canal: Common Law Approaches to a Modern Tragedy, 11 ENVTL. L. 133 (1980). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. proposed the development of a modern industrial city, fed by cheap hydroelectric power from Niagara Falls. Love’s neighborhood would feature a canal that connected both branches of the Niagara River. With financial backing and a state charter for the project, Love started digging his canal. The project was ultimately doomed by the Panics of 1893 and 1907,[2]Alexander Dana Noyes. Forty Years of American Finance: A Short Financial History of the Government and People of the United States since the Civil War, 1865-1907 (1909). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Taxation & Economic … Continue reading and Nikola Tesla unlocking alternating current as the means to transmit electricity cheaply and efficiently over long distances.

Beginning in the 1920s, Love’s canal was used as a dump by the city of Niagara Falls until it was bought by Hooker Chemical Company in 1947. Hooker had actually started dumping chemical waste into the canal in 1942 and continued doing so until 1953, eventually dumping about 21,800 tons of chemical waste[3]Norman Nosenchuck, The Cleanup of Love Canal, 11 EPA J. 7 (1985). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. into the canal. For reference, that’s about 3,700 African elephants or 16,000 Honda Civics in a 16-acre area.

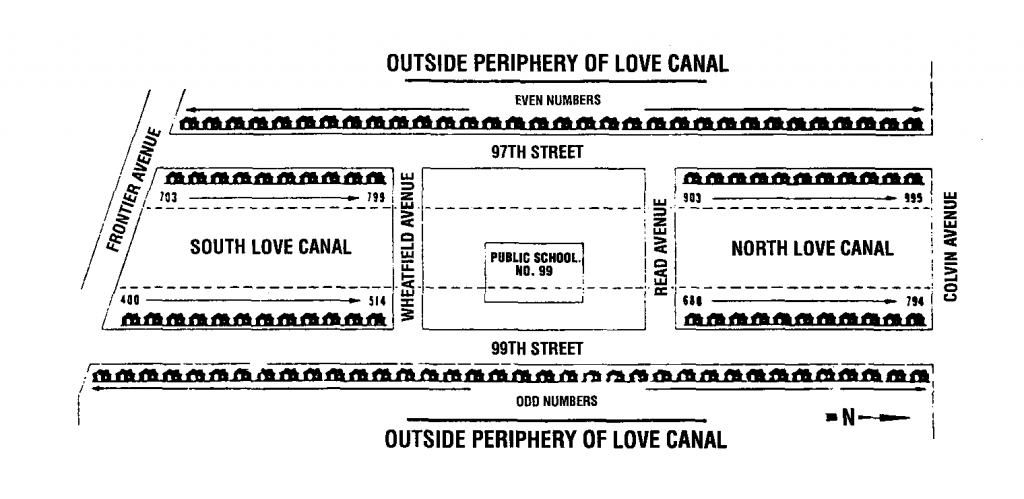

In 1953, Hooker covered over the canal with earth and sold it to the Niagara Falls Board of Education for $1. In the deed, Hooker warned the Board that “the premises…have been filled….with waste products resulting from the manufacturing of chemicals….no claim, suit, action or demand of any nature whatsoever shall ever be made….for injury to a person or persons, including death…in connection with or by reason of the presence of said industrial waste.”[4]Jay S. Albanese, Love Canal Six Years Later: The Legal Legacy, 48 FED. PROBATION 53 (1984). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. But Niagara Falls was booming in population at this time, and a school and playground were built on top of the covered canal. Eventually, the Board sold part of the land to a developer who built about 100 houses nearby. The new neighborhood was named in honor of William Love’s utopian dream: Love Canal. By 1980, approximately 1,000 families lived within 1,800 feet of Love’s old canal.[5]Love Canal study & habitability statement : hearing before the Subcommittee on Commerce, Transportation, & Tourism of the Committee on Energy & Commerce, House of Representatives, Ninety-seventh Congress, second session, August 9, … Continue reading

A Ticking Time Bomb

Warning signs of the disaster percolating under Niagara County’s clay were present from the start. Children playing outdoors returned home with chemical burns on their hands and faces[6]Edkardt C. Beck, The Love Canal Tragedy, 5 EPA J. 17 (1979). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and a chemical odor hung in the air. A “greenish luminescence”[7]Mary Louise Williams, Minamata and Love Canal: A Pollution Tale of Two Cities, 17 Update on L. Related Educ. 7 (1993). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. could be seen floating above the old filled in canal on humid summer nights. Anecdotally, neighbors whispered to each other about experiencing a high number of miscarriages and having children born with birth defects.[8]Theodore Baurer, Love Canal: Common Law Approaches to a Modern Tragedy, 11 ENVTL. L. 133 (1980). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

After a particularly snowy winter, runoff from melting snow in the spring of 1976 brought the worst chemical stench Love Canal residents had ever experienced. A strange black ooze[9]Mary Louise Williams, Minamata and Love Canal: A Pollution Tale of Two Cities, 17 Update on L. Related Educ. 7 (1993). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. permeated basement walls. Corroded steel drums burst from the ground like apocalyptic zombies. Residents complained to the local paper, looking for answers about what was happening in their neighborhood.

Frustratingly, the city of Niagara Falls and New York State ignored residents’ concerns; the county instead threatened to fine residents[10]Mary Louise Williams, Minamata and Love Canal: A Pollution Tale of Two Cities, 17 Update on L. Related Educ. 7 (1993). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. if they didn’t stop pumping the black ooze out of their basements and into the city sewer system. In October 1976, local newspapers revealed that the mysterious black ooze seeping into Love Canal basements contained PCBs, benzene,[11]Mary Louise Williams, Minamata and Love Canal: A Pollution Tale of Two Cities, 17 Update on L. Related Educ. 7 (1993). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and vinyl chloride[12]Health effects of toxic pollution : a report from the Surgeon General ; &, A brief review of selected environmental contamination incidents with a potential for health effects : reports / prepared by the Surgeon General, Department of Health … Continue reading (the same chemical released in East Palestine). Eventually, more than 80 compounds would be identified in the air and walls of residents’ basements, including multiple known carcinogens.

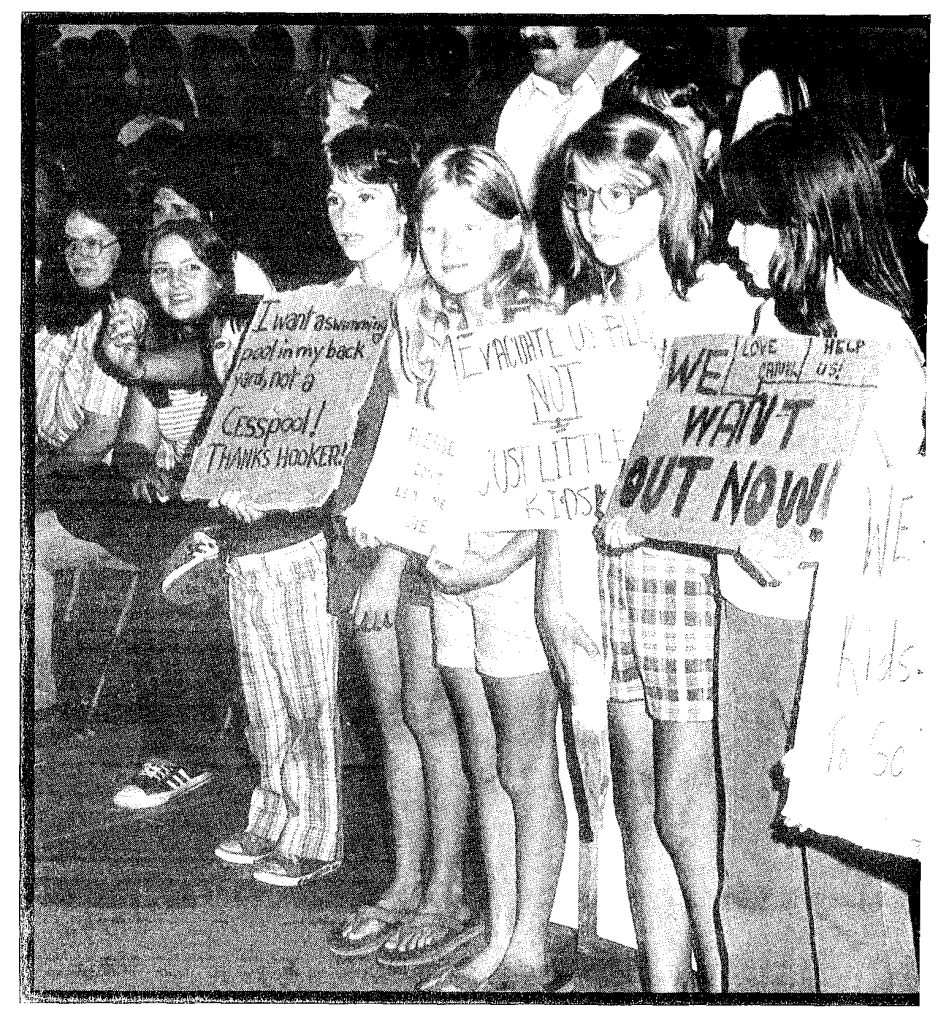

For two years residents lobbied and organized for help, primarily led by Lois Gibbs, whose son developed epilepsy after he started attending school in 1977. After their work received national media attention, the New York State Commissioner of Health finally declared a public health emergency[13]Jay S. Albanese, Love Canal Six Years Later: The Legal Legacy, 48 FED. PROBATION 53 (1984). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. on August 2, 1978 at Love Canal. Five days later, President Carter declared the Love Canal site a federal disaster area—the first emergency declaration for a non-natural disaster.[14]Sedina Banks, The Erin Brockovich Effect: How Media Shapes Toxics Policy, 26 Environs: ENVTL. L. & POL’y J. 219 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Evacuations were ordered and the state began buying abandoned homes at the tune of $10 million.[15]Jay S. Albanese, Love Canal Six Years Later: The Legal Legacy, 48 FED. PROBATION 53 (1984). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

In December 1979, the Department of Justice sued Hooker Chemical[16]Love Canal study & habitability statement : hearing before the Subcommittee on Commerce, Transportation, & Tourism of the Committee on Energy & Commerce, House of Representatives, Ninety-seventh Congress, second session, August 9, … Continue reading on behalf of the EPA for violating the Clean Water Act at Love Canal and at three other sites in Niagara Falls; the suit was settled in 1995. In May 1980, President Carter issued a second emergency declaration for Love Canal, expanding the original evacuation zone to include an additional 710 families. However, some 140 families[17]Norman Nosenchuck, The Cleanup of Love Canal, 11 EPA J. 7 (1985). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. in this expanded evacuation zone chose to stay. Demolition of abandoned homes began in 1982.

Super Funds for Super Problems

The Love Canal disaster “propelled the problems of inadequate hazardous chemical waste disposal into the national spotlight.”[18]S. Rep. 848, 96th Congress. This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. Across the country, people identified with the nightmare of a seemingly ordinary middle-class neighborhood that was actually a toxic dump, and children being poisoned by their school and home.

At the height of the Love Canal crisis, another environmental disaster oozed into the national spotlight from a dump site in Bullitt County, Kentucky. Known as the Valley of the Drums,[19]1979 KY. Acts 22. This law is found in HeinOnline’s Session Laws. it was a 23-acre area where 100,000 steel drums of chemical waste were improperly dumped over a period of some ten years. As the drums corroded, their contents spilled into nearby waterways until the site came to the attention of the EPA in 1979. Photos of the site were published nationally, giving average Americans a visceral visual of the potential horrors that could be lurking in their backyards.

National outrage and fear over conditions at both the Valley of the Drums and Love Canal directly led to the passage of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980,[20]94 Stat. 2767. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. also known as CERCLA. At the law’s signing, President Carter directly referenced Love Canal and Valley of the Drums, calling them “stark reminders of the neglect in our society.”[21]Jimmy Carter, Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 – Remarks on Signing H.R. 7020 into Law – December 11, 1980, 1980 Pub. Papers 2797 (1980). This paper is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. … Continue reading

The act created the Superfund program, which cleans up sites contaminated by hazardous materials. Superfund cleanups are normally paid for by the primary polluter; if the polluter cannot be identified, then clean up is paid for with taxpayer dollars. In 2021, Congress authorized a tax on chemical manufacturers under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to help pay for Superfund cleanups.

Beginning in 1983, the EPA published its National Priorities List, which identifies the most heavily contaminated sites that will require long-term cleanup. Newly identified sites for inclusion on the NPL are published in the Federal Register and open for public comment. There are 1,890 sites currently on the National Priorities List. The EPA maintains a searchable version of its list on its website, allowing the public to identify if they live near any Superfund sites. Love Canal was added to the NPL in 1983.

Love Canal Today

In 1980, New York State established the Love Canal Area Revitalization Agency (LCARA),[22]1980 NY 1192. This law is found in HeinOnline’s Session Laws. a government agency, to work with the EPA on cleanup and rehabilitation of Love Canal, with the goal of getting people to live in the neighborhood once again. In 2003, the agency’s rehabilitation and resale work was declared complete, and it was abolished that same year.

Love Canal was deleted from the NPL by the EPA in 2004.[23]69 Fed. Reg. 58323. This notice is found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Officially, oversight and maintainence of remedial action done at the site was all that was needed “to be protective of public health.”[24]69 Fed. Reg. 58323. This notice is found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Cleanup controls at Love Canal are reviewed every five years to ensure the site is safe; the last review was done in 2019. Parts of the site remain closed off by chain link fencing, but people once again live in Love Canal, which is known today as Black Creek Village.

Despite assurances that Love Canal is safe, some current residents say the ghosts of the past continue to haunt them, claiming they suffer from abnormally high rates of miscarriages and mysterious health issues. The culprit, they say, is a 2011 breach of the containment zone during a sewer repair, which has allowed chemicals to migrate and leech into their yards and homes.

According to a search on the EPA’s Cleanups in My Community, there are currently 151 proposed or active Superfund sites in Erie and Niagara counties alone.

You Know That We’re (Not) Toxic

Here at the HeinOnline Blog, we cover a variety of topics, from light-hearted tales of leprechauns to more serious systemic problems. Regardless of what you’re looking for, you will never be poisoned by a bad research experience.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1, ↑8 | Theodore Baurer, Love Canal: Common Law Approaches to a Modern Tragedy, 11 ENVTL. L. 133 (1980). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Alexander Dana Noyes. Forty Years of American Finance: A Short Financial History of the Government and People of the United States since the Civil War, 1865-1907 (1909). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Taxation & Economic Reform in America Parts I & II. |

| ↑3, ↑17 | Norman Nosenchuck, The Cleanup of Love Canal, 11 EPA J. 7 (1985). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑4, ↑13, ↑15 | Jay S. Albanese, Love Canal Six Years Later: The Legal Legacy, 48 FED. PROBATION 53 (1984). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑5, ↑16 | Love Canal study & habitability statement : hearing before the Subcommittee on Commerce, Transportation, & Tourism of the Committee on Energy & Commerce, House of Representatives, Ninety-seventh Congress, second session, August 9, 1982. (1983). This hearing is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. |

| ↑6 | Edkardt C. Beck, The Love Canal Tragedy, 5 EPA J. 17 (1979). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑7, ↑9, ↑10, ↑11 | Mary Louise Williams, Minamata and Love Canal: A Pollution Tale of Two Cities, 17 Update on L. Related Educ. 7 (1993). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑12 | Health effects of toxic pollution : a report from the Surgeon General ; &, A brief review of selected environmental contamination incidents with a potential for health effects : reports / prepared by the Surgeon General, Department of Health & Human Services, & the Congressional Research Service of the Libr of Congress for the Committee on Environment & Public Works, U.S. Senate at the request of Edmund S. Muskie, John C. Culver, & Robert T. Stafford. (1980). This committee print is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. |

| ↑14 | Sedina Banks, The Erin Brockovich Effect: How Media Shapes Toxics Policy, 26 Environs: ENVTL. L. & POL’y J. 219 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑18 | S. Rep. 848, 96th Congress. This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑19 | 1979 KY. Acts 22. This law is found in HeinOnline’s Session Laws. |

| ↑20 | 94 Stat. 2767. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑21 | Jimmy Carter, Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 – Remarks on Signing H.R. 7020 into Law – December 11, 1980, 1980 Pub. Papers 2797 (1980). This paper is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑22 | 1980 NY 1192. This law is found in HeinOnline’s Session Laws. |

| ↑23, ↑24 | 69 Fed. Reg. 58323. This notice is found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register |