Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse last month shocked the economic world. Its implosion was the second-largest bank failure in United States history. Within one week, three U.S. banks failed: Silicon Valley Bank, Silvergate Bank, and Signature Bank. On the heels of these collapses, Credit Suisse, a major global investment bank, was rescued from collapse by the Swiss government and UBS, the largest Swiss bank.

Silicon Valley Bank failed after it announced it had sold over $1 billion in securities at a loss—and needed an infusion of $2.25 billion to support itself. Investors panicked over this news and triggered a bank run, withdrawing $42 billion in deposits in a matter of days. Suddenly insolvent, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) took control of the bank.

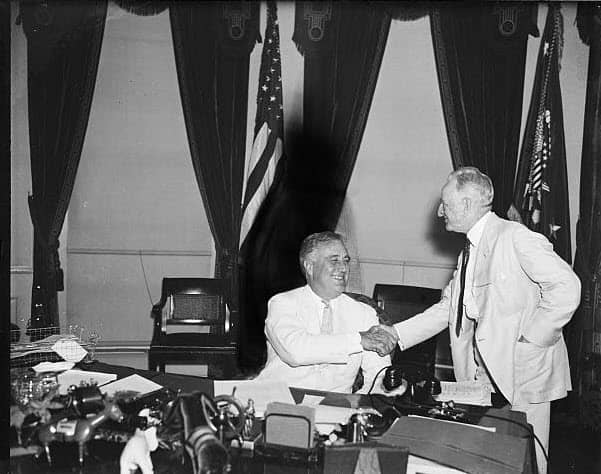

Silicon Valley Bank’s failure immediately brought to mind the 2008 financial crisis, both in pundit talking points and in the minds of ordinary citizens. Terms like “bank run” may have brought to mind a specific scene in It’s a Wonderful Life, and may have caused some to wonder: weren’t laws passed to prevent this exact scenario after the Great Depression? The banking world did undergo a major transformation as a result of the Great Depression. Using HeinOnline, let’s explore the monumental New Deal legislation that created today’s banking world, all of which was passed within the first 100 days of Roosevelt’s presidency.

FDR’s Bank Holiday

Franklin D. Roosevelt[1]Franklin D. Roosevelt; B. D. Zevin, Editor. Nothing to Fear: The Selected Addresses of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1932-1945 (1946). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. was sworn in as the 32nd president of the United States on March 4, 1933, at the height of the Great Depression. The previous year, 1932, had been particularly brutal. Unemployment was at 25%[2]Monetary and Fiscal Policy in the Current Environment, 1993 Econ. Rep. Pres. 73 (1993). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. and bank runs and closings were common occurrences. Nearly 1,500 banks suspended operations in 1932,[3]Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation: The First Fifty Years: A History of the FDIC, 1933-1983 (1984). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Taxation & Economic Reform in America. which was actually a decrease from the previous year, when almost 2,300 banks were suspended.

Two days after his inauguration, President Roosevelt declared a bank holiday.[4]Franklin D. Roosevelt. Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. Under the proclamation, from March 6 to March 9 all banks would close and all bank transactions were halted. The bank holiday was designed to prevent the “hoarding” of gold and silver currency, a real problem as faith in paper currency plummeted.

The day the holiday was set to lift, March 9, Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act.[5]48 Stat. 1. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. The act gave Roosevelt the power to extend[6]Franklin D. Roosevelt. Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. the bank holiday until March 13.

The Emergency Banking Act

The Emergency Banking Act was furiously written in three days, starting the night after Roosevelt’s inauguration[7]Brief History of Emergency Powers in the United States: A Working Paper (1974). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. to be ready in time for a special session of Congress. The Act’s commanding general was new Secretary of the Treasury William H. Woodin, “a marvelous guitar-playing imp of a man.”[8]Richard L. Tobin. Decisions of Destiny (1961). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. To help get the bill written, bank experts from the departing Hoover administration stayed on to help. Raymond Moley, Roosevelt’s speechwriter and part of his “Brain Trust”[9]Herbert Hoover. Memoirs of Herbert Hoover (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. inner circle of advisors, described the frantic work on the bill as, “We’d forgotten to be Republicans or Democrats. We were just a bunch of men trying to save the banking system.”[10]Richard L. Tobin. Decisions of Destiny (1961). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library.

Their hard work paid off: the bill passed[11]Richard L. Tobin. Decisions of Destiny (1961). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. after an hour of debate in the House at 4:00pm, and by 7:30pm it passed in the Senate. No member of Congress actually read the bill; there had been no time to print copies, since Roosevelt made corrections to the draft up until noon. President Roosevelt signed it into law that same evening.

Broken into five sections, or titles, the Emergency Banking Act:

- expands the president’s power during a banking crisis and retroactively approved the banking holiday and the president’s injunction on hoarding, exporting, or melting of gold and silver coin, bullion, and currency

- gives the Comptroller of the Currency the power to appoint conservators for insolvent banks to conserve their assets

- allows the Secretary of the Treasury to determine if a bank needs more assets to operate. If it did, the president could authorize the Reconstruction Finance Corporation “to subscribe for preferred stock in such association”[12]48 Stat. 1. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large.

- lets the Federal Reserve issue bank notes, an emergency currency backed by the government

- ends with a procedural section which made the Act effective

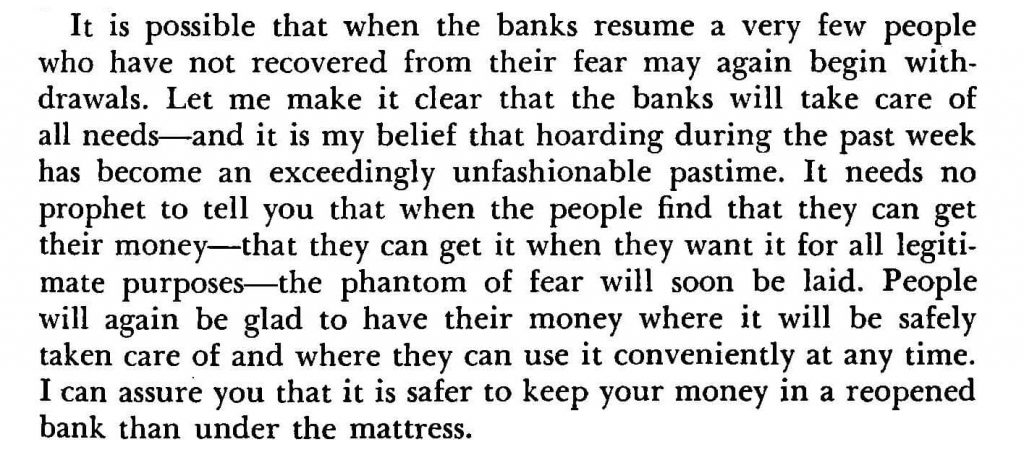

The night before banks reopened, Roosevelt gave the first of his Fireside Chats.[13]Franklin D. Roosevelt; B. D. Zevin, Editor. Nothing to Fear: The Selected Addresses of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1932-1945 (1946). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. In his address, Roosevelt explained steps the government had taken to shore up the country’s financial institutions and to quell any fears remaining in ordinary Americans. “I can assure you that it is safer to keep your money in a reopened bank than under the mattress,”[14]Franklin D. Roosevelt; B. D. Zevin, Editor. Nothing to Fear: The Selected Addresses of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1932-1945 (1946). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. Roosevelt said.

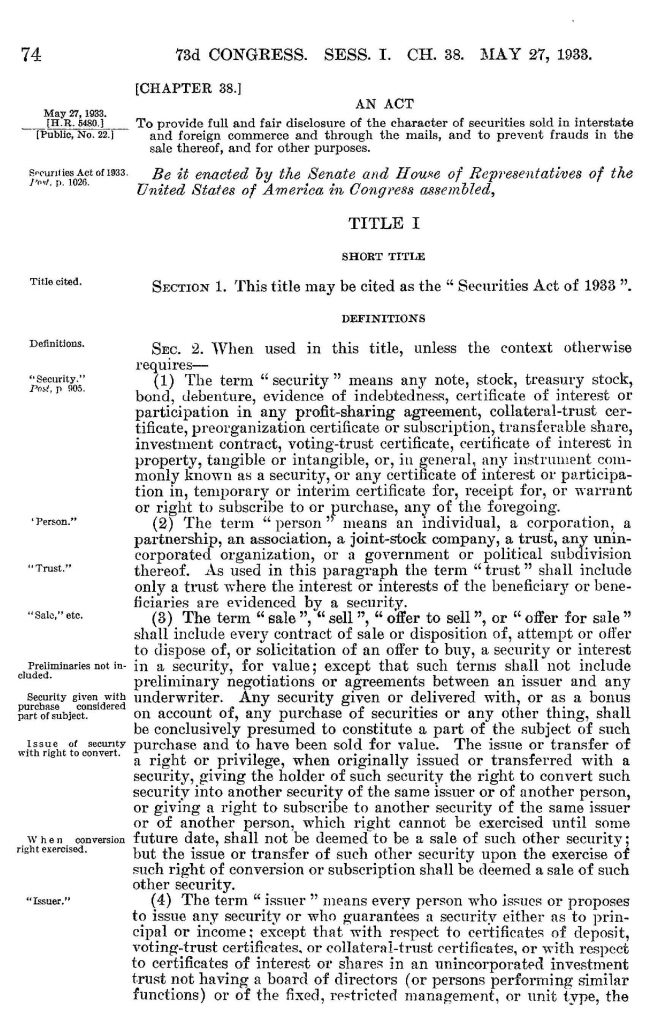

The Securities Act of 1933

Two months after the Emergency Banking Act was signed into law, the Securities Act of 1933[15]48 Stat. 74. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. also became law. The new law completely reshaped securities regulations in the United States. In layman’s terms, securities are any financial instruments that have monetary value and can be traded. Examples include stocks, bonds, and mutual funds. Prior to the Act’s passage, securities regulation was done at the state level through blue sky laws.[16]Jonathan R. Macey & Geoffrey P. Miller, Origin of the Blue Sky Laws, 70 TEX. L. REV. 347 (1991). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Their name allegedly originated from claims that “many securities salesmen were so dishonest that they would sell ‘building lots in the blue sky.'”[17]Paul G. Mahoney, The Origins of the Blue-Sky Laws: A Test of Competing Hypotheses, 46 J.L. & ECON. 229 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

The main purpose of the Securities Act of 1933 was to increase transparency about the nature of securities that were being sold. Issuers were required to disclose to investors exactly what they were buying, including any risks. Enforcement was primarily done by requiring securities to be registered with the Federal Trade Commission, and there were strict liabilities for any misrepresentations or errors in the registrations.[18]John Hanna & Edgar Turlington, Securities Act of 1933, 28 ILL. L. REV. 482 (1933-1934). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. The following year, when the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 was passed, the Securities and Exchange Commission was created, which took over registration and enforcement duties from the Federal Trade Commission.

Banking Act of 1933 (the Glass-Steagall Act)

The following month, one of the most transformative and controversial banking laws was passed: the Banking Act of 1933,[19]48 Stat. 162. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. also commonly known as the Glass-Steagall Act after its two sponsors, Senator Carter Glass and Representative Henry B. Steagall.

The Banking Act of 1933 separated commercial banking from investment banking and created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Separating commercial and investment banking was a long-running project of Senator Glass; he had been introducing legislation to do that since 1930. Glass and other congressmen partially blamed the 1929 stock market crash on commercial banks taking risks in the volatile stock market with their holdings instead of investing in their communities.

Under the Act, banks were given one year to decide if they would specialize in commercial or investment banking. Commercial banks could not underwrite or deal in securities and their income from securities was capped at ten percent. Investment banks could not share directors or owners with commercial banks, effectively separating the two entities.

Crucially, the Act created deposit insurance, originally up to $2,500, with a provision for the insurance amount to increase to $5,000 the following year. This limit has increased handful of times over the years, with its last increase in 2008 to $250,000. Deposit insurance was a controversial provision in the bill, and originally was not supported by Glass or President Roosevelt.[20]Jacob H. Gutwillig, Glass versus Steagall: The Fight over Federalism and American Banking, 100 VA. L. REV. 771 (2014). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. But federal deposit insurance had broad support from small banks[21]Nicholas Economides, R. Glenn Hubbard & Darius Palia, Federal Deposit Insurance: Economic Efficiency or Politics, 22 REGULATION 15 (1999). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and was ultimately included. Of the compromise, Senator Glass said, “The executive authorities at the outset were all thoroughly opposed to the insurance of bank deposits…But as sensible men, we realized that it was a problem from which we could not escape.”[22]Nicholas Economides, R. Glenn Hubbard & Darius Palia, Federal Deposit Insurance: Economic Efficiency or Politics, 22 REGULATION 15 (1999). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

Although the Banking Act of 1933 was not initially supported by Roosevelt and was not technically part of his New Deal, Roosevelt advocated for the legislation to the American people.[23]H. Parker Willis; John M. Chapman. Banking Situation: American Post-War Problems and Developments (1934). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Taxation & Economic Reform in America. Today, no discussion of Roosevelt’s New Deal banking legislations is complete without including the Banking Act of 1933.

A New Deal for the Academic Researcher

Here at HeinOnline, we strive to make research quick, intuitive, and fun with a suite of custom tools and millions of pages of content. The HeinOnline Blog is a great place to learn the ins and outs of research and to get inspired on the myriad topics and primary resources you can find in HeinOnline. Hit the subscribe button to stay in the know.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1, ↑13, ↑14 | Franklin D. Roosevelt; B. D. Zevin, Editor. Nothing to Fear: The Selected Addresses of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1932-1945 (1946). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Monetary and Fiscal Policy in the Current Environment, 1993 Econ. Rep. Pres. 73 (1993). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑3 | Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation: The First Fifty Years: A History of the FDIC, 1933-1983 (1984). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Taxation & Economic Reform in America. |

| ↑4, ↑6 | Franklin D. Roosevelt. Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑5, ↑12 | 48 Stat. 1. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑7 | Brief History of Emergency Powers in the United States: A Working Paper (1974). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑8, ↑10, ↑11 | Richard L. Tobin. Decisions of Destiny (1961). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑9 | Herbert Hoover. Memoirs of Herbert Hoover (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑15 | 48 Stat. 74. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑16 | Jonathan R. Macey & Geoffrey P. Miller, Origin of the Blue Sky Laws, 70 TEX. L. REV. 347 (1991). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑17 | Paul G. Mahoney, The Origins of the Blue-Sky Laws: A Test of Competing Hypotheses, 46 J.L. & ECON. 229 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑18 | John Hanna & Edgar Turlington, Securities Act of 1933, 28 ILL. L. REV. 482 (1933-1934). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑19 | 48 Stat. 162. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑20 | Jacob H. Gutwillig, Glass versus Steagall: The Fight over Federalism and American Banking, 100 VA. L. REV. 771 (2014). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑21, ↑22 | Nicholas Economides, R. Glenn Hubbard & Darius Palia, Federal Deposit Insurance: Economic Efficiency or Politics, 22 REGULATION 15 (1999). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑23 | H. Parker Willis; John M. Chapman. Banking Situation: American Post-War Problems and Developments (1934). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Taxation & Economic Reform in America. |