This month, Sandra Day O’Connor passed away at the age of 93. Known as the first woman to serve as a United States Supreme Court Justice, she held the balance of power on the court for almost two decades.

O’Connor, recognized as a moderate conservative, was also well-known for her meticulously researched viewpoints. A true trailblazer for future women of the high court, she was admired for the mark she left in a male-dominated field.

Sowing the Seeds of Justice

Born on March 26, 1930, Sandra Day was raised on a ranch near Duncan, Arizona, where she lived a rustic upbringing without electricity or running water until she was seven. At her home on a cattle ranch, she learned how to change a tire and enjoyed shooting coyotes and jackrabbits with her .22-caliber rifle. A country girl at heart, Day spent most of her time living with her maternal grandmother while attending a private school for girls.

At the ripe age of 16, Day began her studies at Stanford University, graduating magna cum laude with a B.A. in economics. Subsequently, she pursued her law degree at Stanford Law School and completed it in 1952. It was here that she served on the Stanford Law Review and also dated then editor-in-chief (and former Supreme Court Chief Justice) William Rehnquist. He later proposed to her, as did three other men, but Day declined his offer. Six months after she graduated from law school, she married John Jay O’Connor III on her family’s ranch.

Facing gender biases, O’Connor experienced difficulty securing a paid job. She worked unpaid as a deputy county attorney in San Mateo, California; however, she was later transitioned to a salaried position. Throughout the next few years, O’Connor had three sons and dedicated herself to political involvement and public service. [1]Colleen A. Daugherty, A Tribute to Sandra Day O’Connor, 29 HAMLINE L. REV. 17 (2006). This article can be found in HeinOnlne’s Law Journal Library. In 1969, she was appointed to the Arizona Senate and by 1973 became the first woman to serve as a state’s Majority Leader.

Balancing the Scales

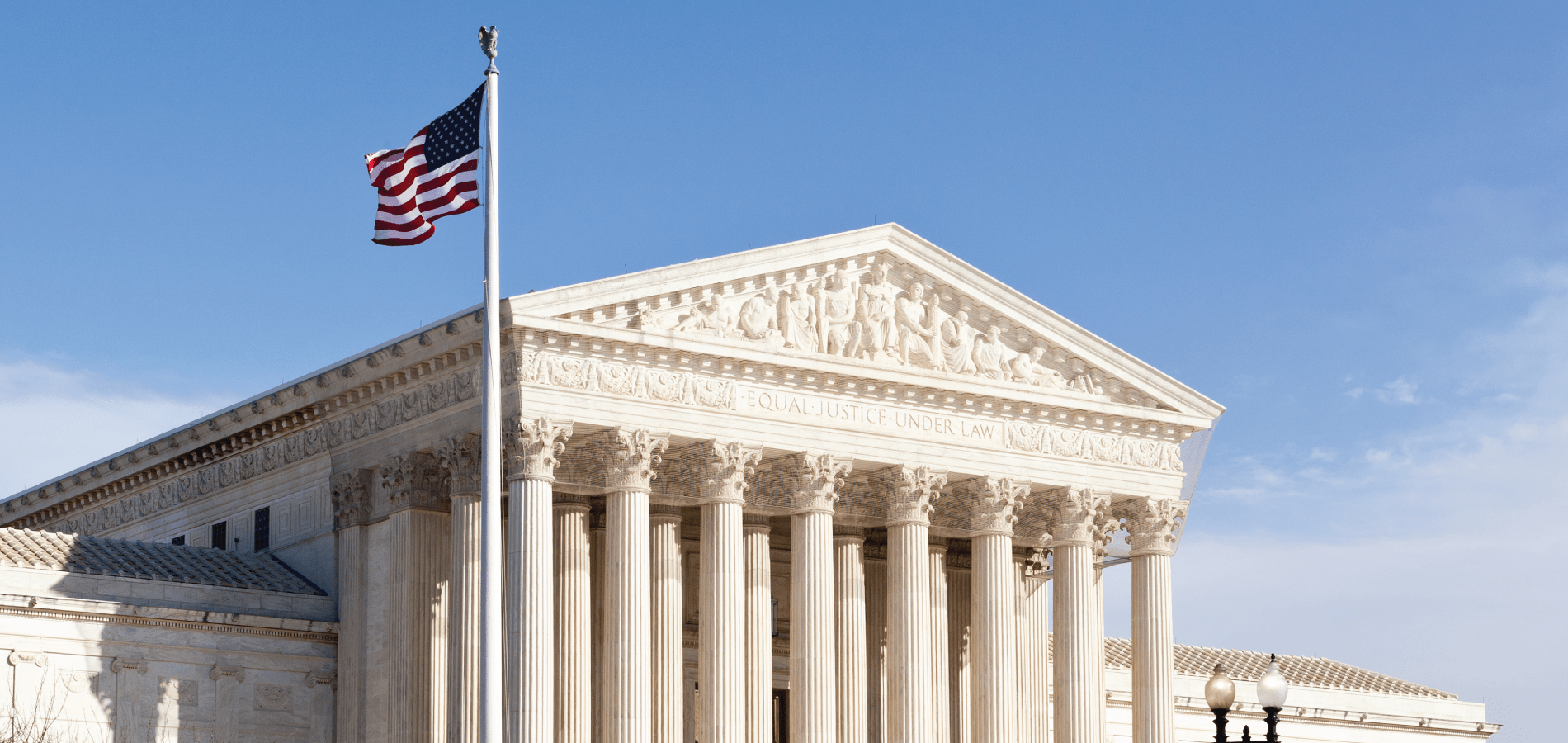

In his 1980 presidential campaign, Ronald Reagan pledged to nominate a woman to the U.S. Supreme Court. By 1981, Reagan fulfilled his promise by nominating O’Connor, who was unanimously confirmed by the Senate on September 21, 1981. She said herself, “Ronald Reagan knew that his decision wasn’t about Sandra Day O’Connor; it was about women everywhere. It was about a nation that was on its way to bridging a chasm between genders that has divided us for too long.”[2]Scott Bales, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor: No Insurmountable Hurdles, 58 STAN. L. REV. 1705 (2006). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

Throughout a significant portion of the 1980s and beyond, O’Connor played a pivotal role in shaping the outcomes of various contentious issues, ranging from abortion rights to the contested presidential election of 2000. For some time the Court was informally called the “O’Connor Court,”[3]George Steven Swan, The Political Economy of the O’Connor Court: Professor Thomas M. Keck Vindicated, 33 OKLA. CITY U. L. REV. 151 (2008). This article can be found in HeinOnlne’s Law Journal Library. as she was the deciding vote in many cases. Moreover, her voting record and opinions demonstrate her commitment to deciding a case based on its facts.

Here are a few notable opinions authored by Justice O’Connor:

- Sutton et al. v. United Air Lines, Inc. (Americans with Disabilities Act)

- Tison v. Arizona (Capital Punishment)

- McConnell v. Federal Election Comm’n (Election Law)

- Mississippi Univ. for Women v. Hogan (Equal Protection)

- Oregon v. Elstad (Fifth Amendment and Miranda Rights)

- Florida Bar v. Went For It, Inc., et al. (Freedom of Speech)

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania et al. v. Casey (Regulation of Abortion)

- Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education (Sexual Harassment in Schools)

- Shaw v. Reno (Voting Rights)

- Bush v. Gore (President Election)

Decoding O’Connor: Feminist or Not?

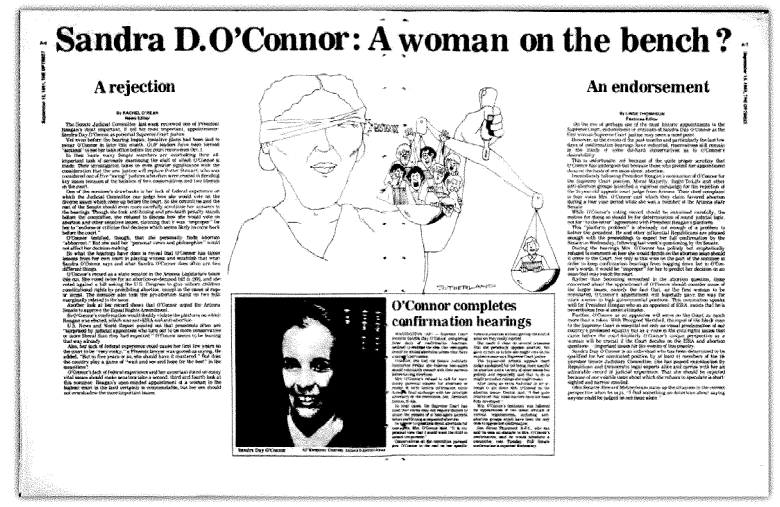

Whether or not Sandra Day O’Connor was considered a feminist has been highly debated. While during the Senate Judiciary Committee hearings O’Connor said she was personally opposed to abortion,[4]Roy M.; Jacobstein, J. Myron, Compilers Mersky. Supreme Court of the U.S. Hearings and Reports on Successful and Unsuccessful Nominations of Supreme Court Justices by the Senate Judiciary Committee. This document can be found in … Continue reading many anti-abortion groups felt she had made pro-abortion votes during her time as a member of the Arizona Legislature. O’Connor was unwilling to promise to overturn Roe. She criticized Roe v. Wade, and argued that “it cannot be supposed as a legitimate or useful framework for accommodating the women’s rights and the State’s interest.” [5]Judith Olans Brown, Wendy E. Parmet & Mary E. O’Connell, The Rugged Feminism of Sandra Day O’Connor, 32 IND. L. REV. 1219 (1999). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Debates persist over her impact on gender equality, with some contending that while she made significant strides, there were instances where progress seemed to be set back. Although O’Connor was viewed as conservative, it was clear that she was going to make up her own mind on specific cases.

In conclusion, O’Connor broke down barriers, showing women everywhere that anything is possible. Even though she graduated in the top 10% of her law school class, she faced gender bias. Instead of backing down, she opened up a law firm herself. Once seated on the bench, O’Connor was known for insisting the judges eat lunch together. She even once wrote a letter to correct an editor of The New York Times[6]Barbara C. S. Shea, Sandra Day O’Connor – Woman, Lawyer, Justice: Her First Four Terms on the Supreme Court, 55 UMKC L. REV. 1 (1986). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. who described the court as “nine men,” and referred to herself as FWOTSC (First Woman On The Supreme Court). Upon retirement, she continued her work as a tireless advocate for judicial independence. O’Connor even wrote an introductory essay[7]Sandra Day O’Connor, Judicial Accountability Must Safeguard, Not Threaten, Judicial Independence: An Introduction, 86 DENV. U. L. REV. 1 (2008). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. calling for a better public understanding of judicial accountability. Her inspirational legacy leaves a lasting impact on both women and the field of law.

Law and Legacy in HeinOnline

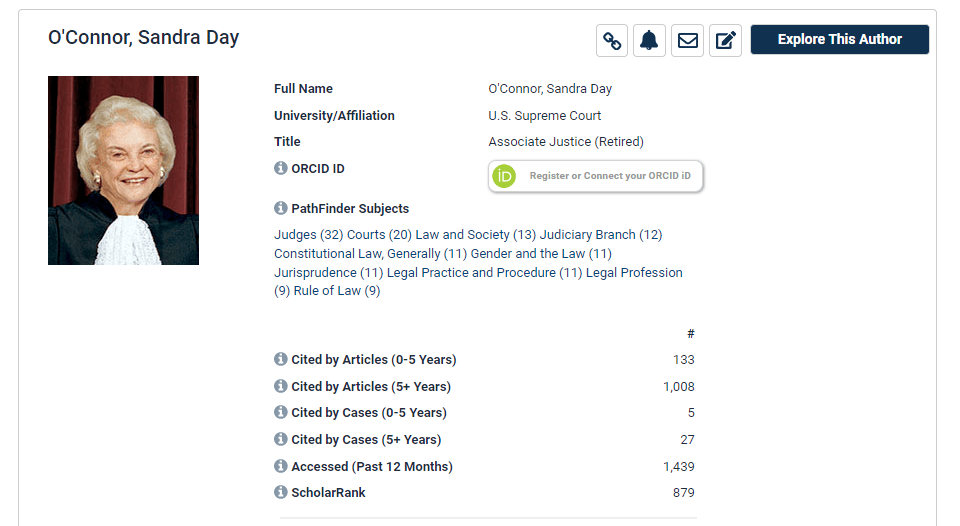

Explore more about Sandra Day O’Connor with HeinOnline. A great place to start is checking out her author profile page which includes nearly 90 articles, comments, and remarks from Sandra Day O’Connor herself.

PRO TIP: You can view all current and past members’ author profiles in this dedicated LibGuide.

Use the Explore this Author option to see what subjects O’Connor actively wrote about, the journals she was most frequently published in, what authors she co-wrote with, and more!

To explore further reading and research, see this annotated bibliography[8]Julie Graves Krishnaswami, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor: A Selected Annotated Bibliography, 57 CATH. U. L. REV. 1099 (2008). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. of O’Connor’s works.

Next, jump over to the History of Supreme Court Nominations database and peruse through both the hearings and reports of the Senate Judiciary Committee specifically for Sandra Day O’Connor. You can also Browse By Justice to see scholarly articles on O’Connor that were carefully selected by our editorial team. Learn even more about the Supreme Court with our latest revamped database, Judges and the Judiciary: Exploring America’s Court System.

High Court Highlights

Want to keep up with what’s going on with SCOTUS? We’ve got you covered. Check out these other useful blog posts and impress your friends with your knowledge of the high court.

- Supreme Court Unveils Its First Ever Code of Ethics

- New Database: Judges and the Judiciary: Exploring America’s Court System

- Major Supreme Court Case Decisions in the 2022-2023 Term

- A Supreme Shake-Up: A Round of 6 Recent Major Supreme Court Rulings

- Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson Confirmed to the Supreme Court

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Colleen A. Daugherty, A Tribute to Sandra Day O’Connor, 29 HAMLINE L. REV. 17 (2006). This article can be found in HeinOnlne’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Scott Bales, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor: No Insurmountable Hurdles, 58 STAN. L. REV. 1705 (2006). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑3 | George Steven Swan, The Political Economy of the O’Connor Court: Professor Thomas M. Keck Vindicated, 33 OKLA. CITY U. L. REV. 151 (2008). This article can be found in HeinOnlne’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑4 | Roy M.; Jacobstein, J. Myron, Compilers Mersky. Supreme Court of the U.S. Hearings and Reports on Successful and Unsuccessful Nominations of Supreme Court Justices by the Senate Judiciary Committee. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s History of Supreme Court Nominations database. |

| ↑5 | Judith Olans Brown, Wendy E. Parmet & Mary E. O’Connell, The Rugged Feminism of Sandra Day O’Connor, 32 IND. L. REV. 1219 (1999). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑6 | Barbara C. S. Shea, Sandra Day O’Connor – Woman, Lawyer, Justice: Her First Four Terms on the Supreme Court, 55 UMKC L. REV. 1 (1986). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑7 | Sandra Day O’Connor, Judicial Accountability Must Safeguard, Not Threaten, Judicial Independence: An Introduction, 86 DENV. U. L. REV. 1 (2008). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑8 | Julie Graves Krishnaswami, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor: A Selected Annotated Bibliography, 57 CATH. U. L. REV. 1099 (2008). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |