Last month, Iowa held its Republican presidential caucus, after which Ron DeSantis dropped out of the race due to lower than expected numbers, falling far behind Trump for second place. A week later, New Hampshire held the first primary election, at which former President Trump again came out ahead for the Republicans, and President Biden won in a landslide over other Democrat candidates, despite the fact that he needed to be written in (the Democratic National Committee recently decided to make South Carolina its first primary to provide more influence to minority voters). All these primaries and caucuses might have you wondering, what’s the difference? In this post, we’ll use HeinOnline’s Voting Rights & Election Law database to dive into the history of caucuses, primaries and the nomination of presidential candidates.

A Brief History of the Election of Candidates

During the nation’s first two presidential elections, the candidates and nominees were selected by the Electoral College. A primary system wasn’t utilized until a two-party system developed in 1796, when politicians were split into the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republicans, headed by Thomas Jefferson. Beginning that year, either a congressional party or state legislature party caucus would determine each party’s presidential candidates. The Anti-Masonic Party held the country’s first national convention[1]Gerald Pomper. Nominating the President: The Politics of Convention Choice (1963). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Voting Rights & Election Law. to nominate a presidential candidate in 1831, because as a third party, they didn’t have any congresspeople to hold a caucus. Primary elections began during the Progressive Era[2]Paula Baker, Comment: Regulating Politics? The Democratic Imperative and American Political Reform, 13 ELECTION L.J. 545 (2014). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Voting Rights & Election Law. in order to limit the influence of corrupt political bosses on delegates in caucuses or national conventions—primaries would allow for popular opinion to guide who the delegates would vote for.

However, the nomination process was still unreliable. The 1968 presidential nominations caused an uproar when, during a year of intense cultural upheaval due to the Vietnam War and the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who supported the Vietnam War, won the Democratic nomination despite not winning a single primary[3]Daisy; et al. de Wolff. Selecting Representative and Qualified Candidates for President: Proposals to Reform Presidential Primaries (2021). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library.. As a result, the Democratic National Committee established the McGovern-Fraser Commission[4]Daisy; et al. de Wolff. Selecting Representative and Qualified Candidates for President: Proposals to Reform Presidential Primaries (2021). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. to recommend new rules for selecting national delegates, and more states established primary elections.

Why Iowa?

Since 1972, Iowa has been the first state to have a contest for a presidential nominee. It goes back to the rules established by the McGovern-Fraser Commission, which included that 30 days notice needed to be provided before hosting a caucus or primary. Iowa already had a fairly extensive nominating process, and with the 30-day window added on, they needed their caucus date moved to early in the election season. However, there have been arguments that Iowa shouldn’t have the first vote, as the state is small and mainly white, and despite the fact that Iowa results don’t always predict the candidate, they do have an impact—DeSantis dropped out of the race for Republican nominee after a poor performance in the Iowa caucus. The Democratic National Convention voted in 2023 to have the first Democratic primary be held in South Carolina to allow for a more diverse population to have more influence.

Primaries and Caucuses: What’s the Difference?

Some key differences between primaries and caucuses include:

- A primary election is run by state or local government, while a caucus is run by a political party.

- Primaries are held throughout the day, while a caucus is held at a specific time on a specific day.

- In a primary, votes are cast via a private ballot, while at a caucus, depending on the party’s rules, voters may split off into groups depending on who they are voting for, and try to convince others to join their group. Delegates are then assigned based on the number of voters in each group.

While many states have switched from caucuses to primaries in order to allow more people to participate, several states still hold onto the caucus system, as it allows candidates and voters to talk about issues important to them. Some states hold both primaries and caucuses, to further add to the confusion. The states that hold caucuses include:

- Iowa

- Nevada (A 2021 law requires Nevada to hold a primary, while the GOP opted to have a caucus this year—hence, the Republicans will have both a primary and a caucus in Nevada, but only the caucus will have any impact on delegates)

- North Dakota

- Wyoming (Holds both primaries and caucuses)

- Missouri

- Michigan (Holds both primaries and caucuses)

- Alaska (Holds both primaries and caucuses)

American Samoa, Guam, and the Virgin Islands also hold caucuses, but because they are U.S. territories, they are unable to participate in the general election.

When it comes to primaries, there are different types, and each state has different rules:

- Open primary:[5]1 (July 11, 2000) Voting in Primary Elections: State Rules on Participation. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. Voters can vote for whoever they want, regardless of their party registration.

- Closed primary:[6]1 (July 11, 2000) Voting in Primary Elections: State Rules on Participation. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. Voters can only vote for a candidate within the party they are registered in.

- Semi-open primary:[7]C. Alan Carillo, I Pledge Allegiance to the Party: Reclaiming the Associational Rights of Independent Voters in Open Primaries, 24 WASH. & LEE J. CIV. RTS. & SOC. JUST. 563 (2018). This article … Continue reading Voters must choose a party-specific ballot, but it doesn’t have to be the party they are registered in.

- Semi-closed primary:[8]Alexander Macheras, Participation in Primary Elections and the Dispositive Eletion Test, 25 B.U. PUB. INT. L.J. 399 (2016). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Voters who aren’t registered in a party can choose a party primary to participate in.

- Additionally, some states such as California, Washington, and Alaska allow voters to vote by ranking candidates.

Meanwhile, different states have different rules for how delegates vote based on the results of the primary or caucus:

- A binding primary or caucus[9]E. Joshua Rosenkranz. Voter Choice ’96: A 50-State Report Card on the Presidential Elections (1996). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Brennan Center for Justice Publications at NYU School of Law database. means that the results of the primary legally bind delegates to vote for the winning candidate at the national election.

- Meanwhile, some binding primaries are also winner take all,[10]7 (September 25, 2003) Electoral College: Reform Proposals in the 107th Congress. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. which means that all delegates will vote for the same candidate.

- In a proportional vote primary,[11]Electing the President: A Report of the Commission on Electoral College Reform (1967). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. delegates will vote in proportion to the number of votes each candidate won in the primary.

- In a non-binding “beauty contest”[12]E. Joshua Rosenkranz. Voter Choice ’96: A 50-State Report Card on the Presidential Elections (1996). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Brennan Center for Justice Publications at NYU School of Law database. election, the primary vote is used to measure the candidates’ popularity, but delegates are not required to vote based on the results.

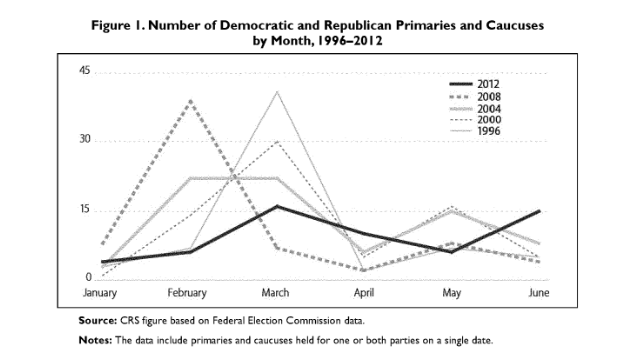

Because there are so many different types of primaries and caucuses, it is important that voters are aware of the rules in their respective states. Additionally, the timing of these elections is spread out over several months to allow candidates time to focus their efforts on as many areas of the country as possible. Efforts of states to front-load their elections[13]5 (October 18, 2012) Contemporary Developments in Presidential Elections. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. at the beginning of the election cycle have diminished in recent decades.

What’s Next for the 2024 Election?

The next major election date is the South Carolina Republican primary on February 24. Republican candidate Nikki Haley,[14]I (2018) Nomination of Hon. Nimrata Nikki Haley, of South Carolina, to Be U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, One Hundred Fifteenth Congress, First Session. This document … Continue reading who has trailed far behind Donald Trump in the initial caucuses and primaries, is holding out hope for the state in which she formerly was governor. Fifty delegates are up for grabs. Three days later, Michigan will be holding primaries for both parties, and a Republican caucus is scheduled for a few days later, on March 2. So far, former President Trump and incumbent President Joe Biden have been front-runners in the Republican and Democratic races, respectively. The biggest day for voting will be Super Tuesday, on March 5, when 16 states and American Samoa will be holding primaries and/or caucuses.

Navigate the Election with HeinOnline’s Voting Rights & Election Law

Browse and search through a collection of thousands of subject-coded titles that illustrate the nuances and complexities of elections and voting systems—the lifeblood of democracy—both in America and across the globe. HeinOnline’s Voting Rights & Election Law database contains books, reports, legislative histories, scholarly articles, a bibliography, and much more to help you understand the history and current complexities of the election system not just in America, but around the world. With the 2024 election already underway, now is the perfect time to add this timely collection to your subscription.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Gerald Pomper. Nominating the President: The Politics of Convention Choice (1963). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Voting Rights & Election Law. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Paula Baker, Comment: Regulating Politics? The Democratic Imperative and American Political Reform, 13 ELECTION L.J. 545 (2014). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Voting Rights & Election Law. |

| ↑3, ↑4 | Daisy; et al. de Wolff. Selecting Representative and Qualified Candidates for President: Proposals to Reform Presidential Primaries (2021). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑5, ↑6 | 1 (July 11, 2000) Voting in Primary Elections: State Rules on Participation. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑7 | C. Alan Carillo, I Pledge Allegiance to the Party: Reclaiming the Associational Rights of Independent Voters in Open Primaries, 24 WASH. & LEE J. CIV. RTS. & SOC. JUST. 563 (2018). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑8 | Alexander Macheras, Participation in Primary Elections and the Dispositive Eletion Test, 25 B.U. PUB. INT. L.J. 399 (2016). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑9, ↑12 | E. Joshua Rosenkranz. Voter Choice ’96: A 50-State Report Card on the Presidential Elections (1996). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Brennan Center for Justice Publications at NYU School of Law database. |

| ↑10 | 7 (September 25, 2003) Electoral College: Reform Proposals in the 107th Congress. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑11 | Electing the President: A Report of the Commission on Electoral College Reform (1967). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑13 | 5 (October 18, 2012) Contemporary Developments in Presidential Elections. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑14 | I (2018) Nomination of Hon. Nimrata Nikki Haley, of South Carolina, to Be U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, One Hundred Fifteenth Congress, First Session. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |