To become President of the United States, a candidate must secure the votes of at least 270 electors in the Electoral College. But what happens if no one gets to 270?

There have been two previous instances, in 1800 and in 1824, in which no single candidate was able to win a majority in the Electoral College. Each of these elections was decided by a contingent election in the House of Representatives. Keep reading to learn about how these elections shaped electoral procedure in the United States, and to speculate on what a tie in the Electoral College might look like today.

Article II and the Electoral College

The President of the United States has never been elected through a direct vote by citizens. Rather, each state appoints a certain number of delegates, referred to as electors, who select the president. Customarily, electors will usually—but not always—select the candidate who wins the popular vote in their state. Article II of the Constitution[1]U.S. Const. art. 2, § 1. This document is available in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated.—the article dictating the procedure for electing the president—provides for each state to appoint a number of electors proportionate to its population, as calculated by combining the number of representatives and senators allotted to each state in Congress. This means that, in practice, states with higher populations have more absolute power in the Electoral College, but states with lower populations wield a disproportionate amount of power, relative to their population.

According to the version of Article II which was in place at the time of the 1800 presidential election, each elector was permitted to cast two votes for president. No distinction was made between votes cast for president or vice president, with the vice president simply being the individual who received the second-highest number of votes overall. In practice, the two major parties at the time—the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists—did designate candidates for president and vice president in a somewhat informal capacity. In 1800, the Democratic-Republicans designated Thomas Jefferson as their presidential candidate and Aaron Burr as their vice-presidential candidate; the Federalists ran John Adams, the incumbent, for president, and nominated Charles Pinckney for vice-president.

The Election of 1800

Contemporary audiences might be most familiar with the election of 1800 from its treatment in the musical Hamilton, which we blogged about back in 2020. The historical reality was even more convoluted. Since electors did not cast votes for vice-president, the parties of the era would customarily plan ahead of time to instruct one of their electors to cast a vote for a third-party candidate or abstain, thus ensuring that the party’s chosen candidate for president received one more vote than their chosen candidate for vice-president. However, something went awry in 1800 when, after the end of a long and bitterly contested campaign,[2]Elizabeth G. Myers, Timing Is Everything: The Social Context behind the Emergence of Separation Ideology during the Presidential Campaign of 1800, 83 TEX L. REV. 933 (2005). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. the Democratic-Republicans emerged victorious with Jefferson and Burr each receiving 73 electoral votes, resulting in a tie between the party’s own presidential and vice-presidential candidates.

According to the Constitution, this tie necessitated a contingent election, to be held in the House of Representatives, in which each House delegation was permitted to cast one vote for president. Things soon became chaotic when voting commenced on February 11, 1801, and it became clear that Aaron Burr and his supporters were campaigning against Thomas Jefferson,[3]Neale, Thomas H. (January 17, 2001). Election of the President & Vice President by Congress: Contingent Election. (CRS Report no. RS20300). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Voting Rights & Election Law collection. their party’s chosen candidate, for the office of president. At the time, there were 16 states in the nation, meaning that a candidate for president needed the votes of nine delegations to win the presidency. In the first round of voting on February 11, Jefferson won eight delegations, Burr won six delegations, and two states split their votes evenly between Burr and Jefferson, resulting in neither candidate winning the necessary nine votes. This was repeated 34 times in the following days, with each result the same. Only with the 36th ballot, on February 17, did two state delegations change their votes, giving Jefferson the necessary majority.

Widespread dissatisfaction with the chaotic election resulted in the first, and so far only, successful reform to the Electoral College in 1803, when Congress proposed the Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution. Replacing the procedure in Article II, Section I, which governed the function of the Electoral College, the amendment dictated that each elector cast separate votes for president and vice president, thus preventing the awkward occurrence of 1800, in which two bitter political opponents found themselves elected to the offices together. The amendment was ratified by the states in June 1804, in time for the presidential election of that year. This reformed Electoral College would be put to the test again only 20 years later, in 1824, when a four-way race for the presidency resulted in no candidates winning a majority.

The Election of 1824

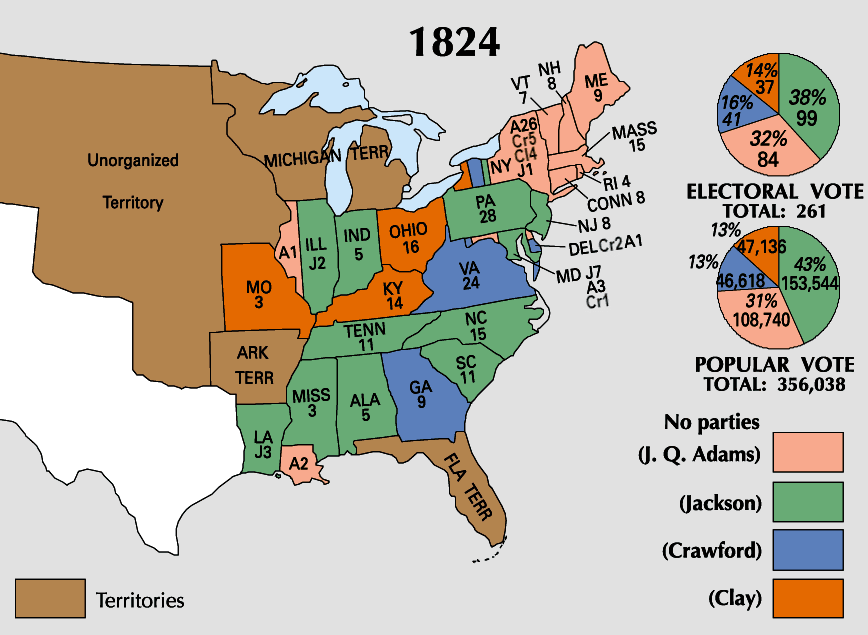

The 1824 election was a crowded race between four candidates: John Quincy Adams (the son of John Adams, who lost to Jefferson in 1800), Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, and William Crawford. Voting took place between October and December 1824. By the end of the process, none of the candidates had achieved a majority in either the Electoral College or popular vote. Jackson, despite not winning a majority, received the most votes: 99 electors and 41.4% of the popular vote. John Quincy Adams came in second, with 84 electors and 30.9% of the popular vote. Crawford and Clay trailed behind, with Crawford receiving 41 electors and 11.2% of the popular vote; and Clay receiving 37 electors and 13% of the popular vote.

With no candidate receiving a majority in the Electoral College, the stage was set for a contingent election, held in the House of Representatives under the guidelines of the Twelfth Amendment. The first—and so far, only—contingent election conducted under the Twelfth Amendment was, in many ways, a much smoother affair than that in 1801. Allies of Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams convened prior to the contingent election, and struck a deal[4]Michael J. McGee, Avoiding a Corrupt Bargain: Ensuring Congress Is Kept Out of a Contingent Presidential Election, 52 U. LOUISVILLE L. REV. 345 (2014). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. in which Clay’s supporters in the House agreed to support Adams’ candidacy, in exchange for Clay being appointed Secretary of State, a post widely seen as a de facto steppingstone to the presidency. On February 9, 1825, with support from Clay, Adams easily won the contingent election[5]House Journal, 118 Cong. 2nd sess. (1824-1825). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. in the House on the first ballot, carrying 13 state delegations, compared to seven for Jackson and four for Crawford.

The outcry following the election of Adams in the House, despite his losing the popular and electoral vote to Jackson, was immediate, with critics denouncing him and Clay at striking a “corrupt bargain”[6]Carl Schurz; John T. Morse, Jr., Editor. Henry Clay – American Statesmen (1899) This book is available in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf collection. for the presidency. Jackson’s supporters were exceptionally bitter, and campaigning for the 1828 election began essentially immediately after Adams’ inauguration.[7]Andrew P. Morriss & Craig Allen Nard, Institutional Choice & Interest Groups in the Development of American Patent Law: 1790-1865, 19 SUP. CT. ECON. REV. 143 (2011). This article can found in … Continue reading Jackson won the 1828 election, defeating Adams, like his father, after a single term in office.

Attempts at Reform

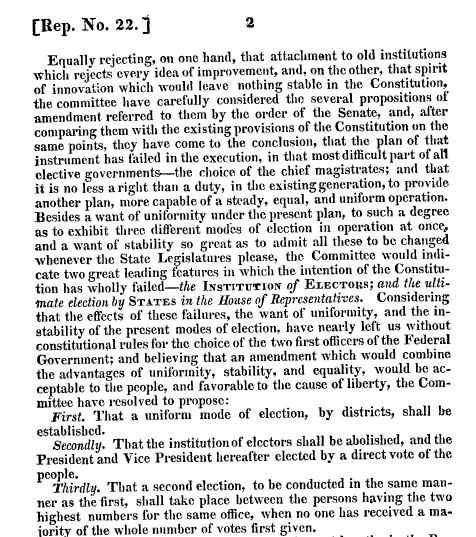

1824 was the second and, so far, the last instance in which an election was decided in the House of Representatives, although there have been a number of contentious elections since, such as the disputed election of 1876, in which victory in the popular vote did not correspond to victory in the Electoral College. Numerous attempts at reforming or abolishing the Electoral College have been made in the years since the election of 1824. The first came only a year after the contingent election of 1825, when an amendment replacing the Electoral College[8]Several resolutions proposing amendments to Constitution, as regards election of President and Vice President of United States, 19 Cong. 1st Sess. (1825-1826). Rep. No. 22. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial … Continue reading with a direct popular vote was proposed in Congress. The amendment failed to gain any traction, and the Electoral College remained—and still remains—the institution that selects the president of the United States.

Additional measures to reform the Electoral College have been presented before Congress in the two centuries since the election of 1824. Beginning in the second half of the twentieth century, calls for reform have increasingly been replaced by calls for abolition, with the introduction of amendments calling for replacing the Electoral College with a system in which presidents are elected by a direct national popular vote. The closest that Congress came to abolishing the Electoral College was the proposed Bayh-Celler amendment[9]Constitutional Amendments, 91 Cong. 1st Sess. (1969). Rep. No. 91-615. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. of 1969, which was advanced by the Senate Judiciary Committee to debate on the floor, only for it to be quickly filibustered by conservative senators from predominantly Southern states.

Recent decades have seen renewed pushes for the abolition of the Electoral College and implementation of a direct popular vote, particularly in the aftermath of the electoral victories of George W. Bush in 2000[10]Neale, Thomas H. (March 29, 2001). The Electoral College: Reform Proposals in the 107th Congress. (CRS Report no. RL30844). and Donald Trump in 2016,[11]Name redacted. (August 24, 2017). The Electoral College: Reform Proposals in the 114th and 115th Congress. (CRS Report no. R44928). both of whom won a majority of electors despite receiving a minority of the popular vote.

Is an Electoral College Tie Possible in 2024?

In short, yes.

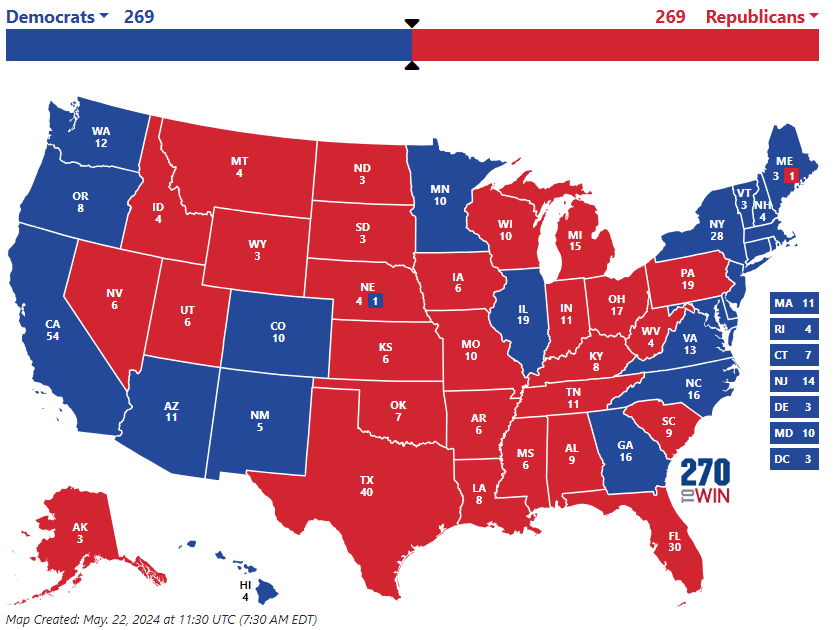

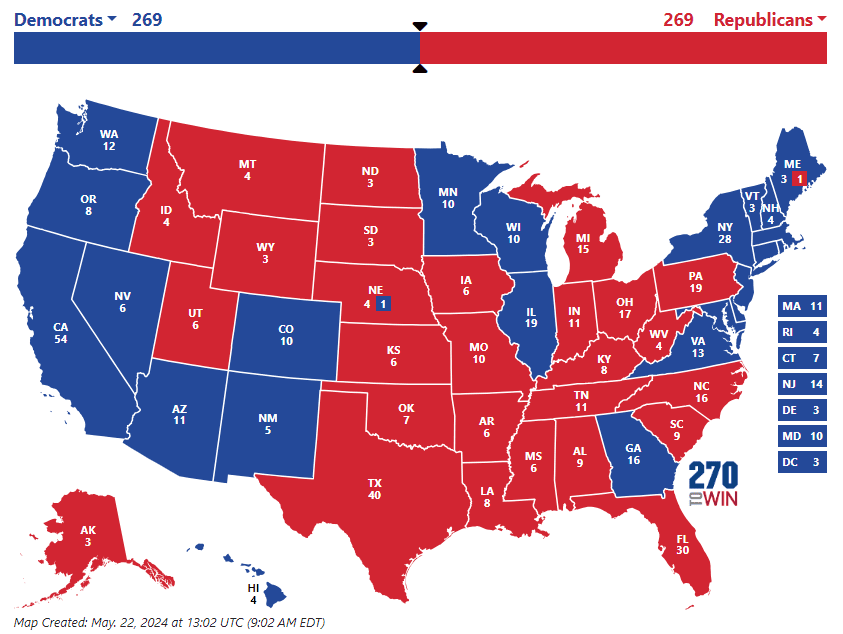

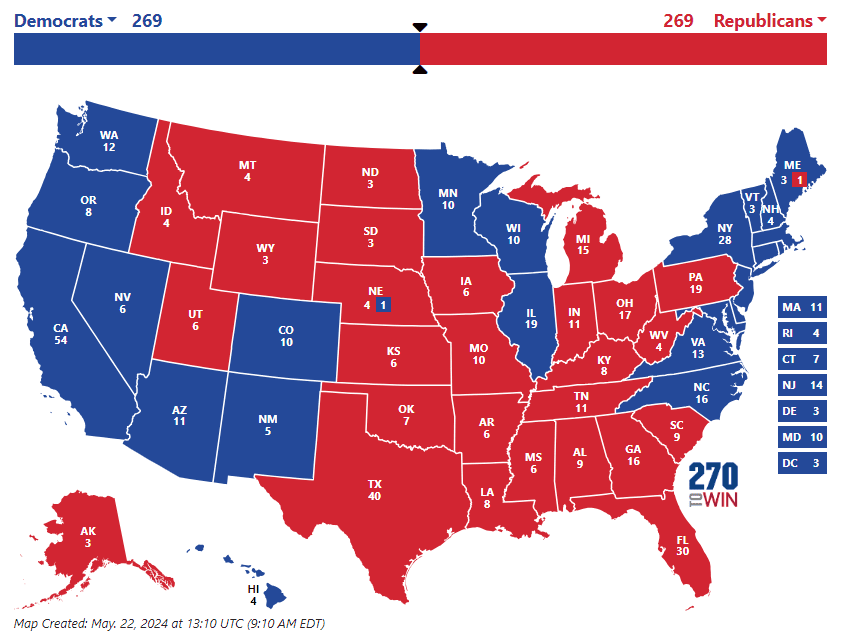

The 2024 presidential race has so far been characterized by two major candidates, both unpopular with the public, polling extremely close together. However, recent years have cast the reliability of pre-election polling into some doubt. The last two presidential election cycles in the United States have proved difficult for pundits to accurately forecast, with pre-election polls in both 2016 and 2020 failing to predict the extent of support[12]Costas Panagopoulos, Polls and Elections: Accuracy and Bias in the 2020 U.S. General Election Polls, 51 PRESIDENTIAL STUD. Q. 214 (2021). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. for Donald Trump, in particular, and to a lesser extent Republican candidates in general. One takeaway from this is that an Electoral College tie—although unlikely—is certainly not out of the realm of possibility. The maps below depict three hypothetical scenarios in which neither major party is able to achieve a majority in the Electoral College. Each scenario hinges on the votes of a handful of states whose outcome was decided by a margin of 5% or less of their popular vote in the previous two elections.

Each of these three scenarios would result in the election being decided in the House of Representatives, according to the procedures established by the Twelfth Amendment. There has not been a contingent election for 200 years, although one in the modern era was depicted memorably (and profanely) in the fifth season of the HBO comedy Veep. Once in the House, the election would be decided by a vote of state congressional delegations, in which each state delegation must choose one candidate. Given the current makeup of the House, with Republicans holding the majority in 26 House delegations and Democrats holding the majority in 22, with two others tied, most analysts view a Republican victory as being the most likely outcome under a Twelfth Amendment election. What happens afterward is, however, more of an open question.

Take a Peek Behind the Polls

Academic research and the study of electoral history provides us with important context for understanding our present political moment. Dig a bit deeper and peek behind the punditry with HeinOnline’s Voting Rights & Election Law database, which covers centuries of history and law pertaining to elections in the United States and across the globe. We also have a dedicated Electoral College subcollection in our U.S. Presidential Library, containing dozens of secondary works on the Electoral College, ranging from the 19th century through the present day.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | U.S. Const. art. 2, § 1. This document is available in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Elizabeth G. Myers, Timing Is Everything: The Social Context behind the Emergence of Separation Ideology during the Presidential Campaign of 1800, 83 TEX L. REV. 933 (2005). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑3 | Neale, Thomas H. (January 17, 2001). Election of the President & Vice President by Congress: Contingent Election. (CRS Report no. RS20300). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Voting Rights & Election Law collection. |

| ↑4 | Michael J. McGee, Avoiding a Corrupt Bargain: Ensuring Congress Is Kept Out of a Contingent Presidential Election, 52 U. LOUISVILLE L. REV. 345 (2014). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑5 | House Journal, 118 Cong. 2nd sess. (1824-1825). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑6 | Carl Schurz; John T. Morse, Jr., Editor. Henry Clay – American Statesmen (1899) This book is available in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf collection. |

| ↑7 | Andrew P. Morriss & Craig Allen Nard, Institutional Choice & Interest Groups in the Development of American Patent Law: 1790-1865, 19 SUP. CT. ECON. REV. 143 (2011). This article can found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑8 | Several resolutions proposing amendments to Constitution, as regards election of President and Vice President of United States, 19 Cong. 1st Sess. (1825-1826). Rep. No. 22. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑9 | Constitutional Amendments, 91 Cong. 1st Sess. (1969). Rep. No. 91-615. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑10 | Neale, Thomas H. (March 29, 2001). The Electoral College: Reform Proposals in the 107th Congress. (CRS Report no. RL30844). |

| ↑11 | Name redacted. (August 24, 2017). The Electoral College: Reform Proposals in the 114th and 115th Congress. (CRS Report no. R44928). |

| ↑12 | Costas Panagopoulos, Polls and Elections: Accuracy and Bias in the 2020 U.S. General Election Polls, 51 PRESIDENTIAL STUD. Q. 214 (2021). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |