Torrential rains pounded the steel town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, on Thursday, May 30, 1889. Over a 24-hour period, six to 10 inches of rain fell on Johnstown, swelling its surrounding creeks and rivers. By the next morning, Johnstown was flooded with two to seven feet of water.

Fourteen miles upstream from Johnstown, Elias Unger, president of the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club, discovered that water levels in Lake Conemaugh had risen so high that it was threatening to crest the dam that contained its waters. And the rain was still falling.

The catastrophic 1889 Johnstown Flood was the greatest single-day loss of civilian life in the United States before September 11, 2001. The disaster also helped rewrite the country’s liability laws. Using HeinOnline, let’s explore the history of this tragedy.

Johnstown before the Deluge

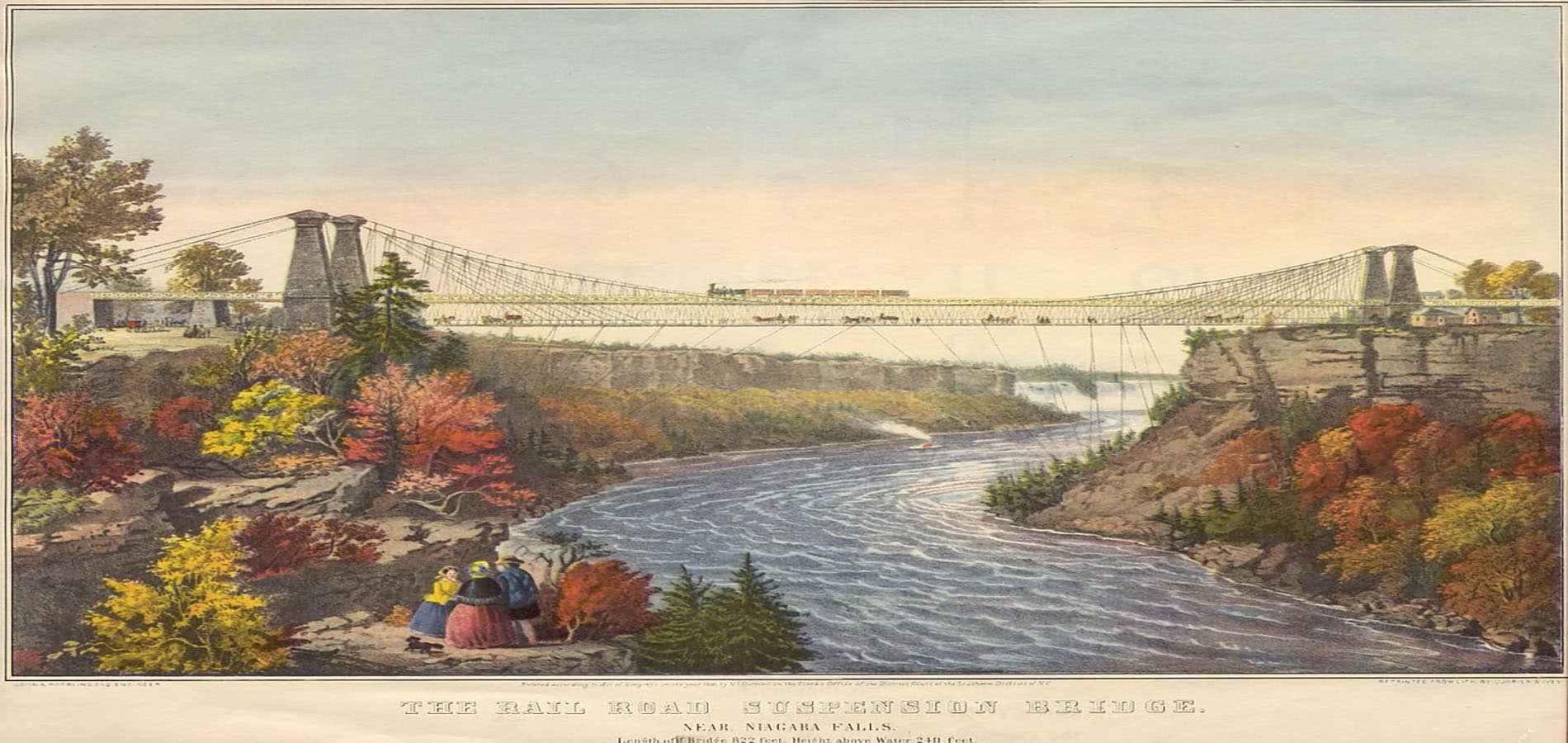

Located on a floodplain approximately 60 miles east of Pittsburgh, Johnstown had experienced floods before. In 1889, Johnstown was home to 30,000 people. Most of its inhabitants worked for the Cambria Iron Company,[1]Lawrence M. Friedman & Joseph Thompson, Total Disaster and Total Justice: Responses to Man-Made Tragedy, 53 DEPAUL L. REV. 251 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. which at the time was the country’s largest producer of steel. High above Johnstown sat the 72-foot high South Fork Dam,[2]H. Rep. 970, at 6 (1963). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. an earth dam built by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania over a 15-year period in the early 1800s as part of the Pennsylvania Main Line Canal.[3]H. Rep. 970, at 6 (1963). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. The dam created Lake Conemaugh, which at the time was perhaps the largest artificial lake in America,[4]H. Rep. 970, at 6 (1963). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. measuring three miles long and more than a mile wide in various spots.

But railroads replaced canal transport shortly after the dam’s completion,[5]Lawrence M. Friedman & Joseph Thompson, Total Disaster and Total Justice: Responses to Man-Made Tragedy, 53 DEPAUL L. REV. 251 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and it sat unused and unmaintained. In 1879, the dam and Lake Conemaugh were sold to a group of wealthy Pittsburgh speculators, led by Carnegie Steel chairman Henry Clay Frick.

The group turned Lake Conemaugh into a private retreat known as the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. Its members were ultra-wealthy industrialists and high-ranking politicians, including Andrew Carnegie,[6]Edward Dies. Behind the Wall Street Curtain (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Taxation & Economic Reform in America. Andrew Mellon, and Philander Chase Knox, giving the club the nickname “The Bosses Club.”[7]Jed Handelsman Shugerman, A Watershed Moment: Reversals of Tort Theory in the Nineteenth Century, 2 J. TORT L. [ii] (2008). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. The group built cottages around Lake Conemaugh and stocked it with fish, but did not prioritize maintaining the old South Fork Dam.[8]S. Rep. No. 108-276 (2004). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

The Dam Fails

Back up at Lake Conemaugh on May 31, as rain continued to fall, Elias Unger was trying to avert disaster. But the dam had no discharge pipe[9]Lawrence M. Friedman & Joseph Thompson, Total Disaster and Total Justice: Responses to Man-Made Tragedy, 53 DEPAUL L. REV. 251 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. to control Lake Conemaugh’s water level. Club workers stacked sandbags on top of the dam and tried to cut in a new spillway. When it became clear that the dam was going to fail, telegrams were sent into Johnstown below, but no warning was issued to townspeople.[10]Lawrence M. Friedman & Joseph Thompson, Total Disaster and Total Justice: Responses to Man-Made Tragedy, 53 DEPAUL L. REV. 251 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

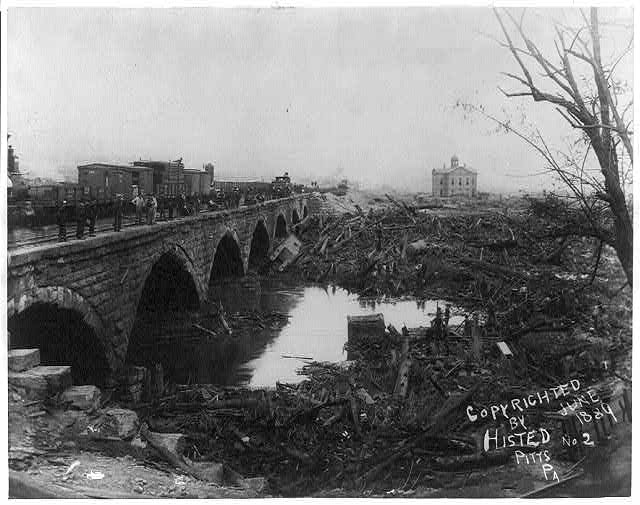

The dam failed that afternoon, sending 20 million tons of water[11]S. Rep. No. 108-276 (2004). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. in a wave 20-feet high[12]Lawrence M. Friedman & Joseph Thompson, Total Disaster and Total Justice: Responses to Man-Made Tragedy, 53 DEPAUL L. REV. 251 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. rushing down into Johnstown at 100 miles per hour.[13]Jed Handelsman Shugerman, The Floodgates of Strict Liability: Bursting Reservoirs and the Adoption of Fletcher v. Rylands in the Guided Age, 110 YALE L.J. 333 (2000). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. It took just 10 minutes[14]Lawrence M. Friedman & Joseph Thompson, Total Disaster and Total Justice: Responses to Man-Made Tragedy, 53 DEPAUL L. REV. 251 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. for the water to travel 14 miles into Johnstown.

Johnstown was obliterated. Along its way, the water picked up trees, railcars and barbed wire from the Cambria Iron Works, which was destroyed, and swept away railroad bridges, sending all of this debris into Johnstown. A 30-acre-wide debris field eventually snagged at the Stone Bridge where it caught fire and burned for three days. The flood caused $17 million in property damage and killed 2,209 people.[15]S. Rep. No. 108-276 (2004). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

After the Johnstown Flood

The day after the flood, reporters from New York and Chicago flocked into Johnstown to report on the disaster. The flood became “the biggest news story since the murder of Abraham Lincoln”[16]Jed Handelsman Shugerman, A Watershed Moment: Reversals of Tort Theory in the Nineteenth Century, 2 J. TORT L. [ii] (2008). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. in 1865. Clara Barton and the new Red Cross arrived in Johnstown for its first undertaking of disaster relief work. Years later, Clara Barton recounted the experience in her history of the Red Cross[17]Clara Barton. Red Cross: A History of This Remarkable International Movement in the Interest of Humanity (1898). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics.:

I shall never lose the memory of my first walk on the day of our arrival—the wading in mud, the climbing over broken engines, cars, heaps of iron rollers, broken timbers, wrecks of houses; bent railway tracks tangled with piles of iron wire; among bands of workmen, squads of military, and getting around the bodies of dead animals, and often people being borne away;—the smoldering fires and drizzling rain—all for the purpose of officially announcing to the commanding general (for the place was under martial law) that the Red Cross had arrived on the field.

Public support and donations poured into Johnstown from around the world, thanks to the disaster’s extensive media coverage. Newspapers reported how the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club’s owners and employees had long ignored signs of the dam’s structural instability.[18]Jed Handelsman Shugerman, A Watershed Moment: Reversals of Tort Theory in the Nineteenth Century, 2 J. TORT L. [ii] (2008). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. On June 7, the county released a report that clearly stated “we hold that the owners are responsible for the fearful loss of life and property.”[19]Jed Handelsman Shugerman, The Floodgates of Strict Liability: Bursting Reservoirs and the Adoption of Fletcher v. Rylands in the Guided Age, 110 YALE L.J. 333 (2000). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. The public and media demanded that the club’s millionaire members compensate victims and survivors. The New York Times wrote in an editorial, “justice is inevitable even though the horror is attributable to men of wealth and station, and the majority of the victims the most downtrodden workers in any industry in the country.”[20]Jed Handelsman Shugerman, The Floodgates of Strict Liability: Bursting Reservoirs and the Adoption of Fletcher v. Rylands in the Guided Age, 110 YALE L.J. 333 (2000). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

Rylands v. Fletcher and Justice for the Victims

At the time of the Johnstown flood, American law operated on fault-based liability, modeling itself on English law. Many survivors sued the club’s owners for negligence. These lawsuits were all unsuccessful[21]Jed Handelsman Shugerman, The Twist of Long Terms: Judicial Elections, Role Fidelity, and American Tort Law, 98 GEO. L.J. 1349 (2010). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. because none were able to successfully prove negligence.

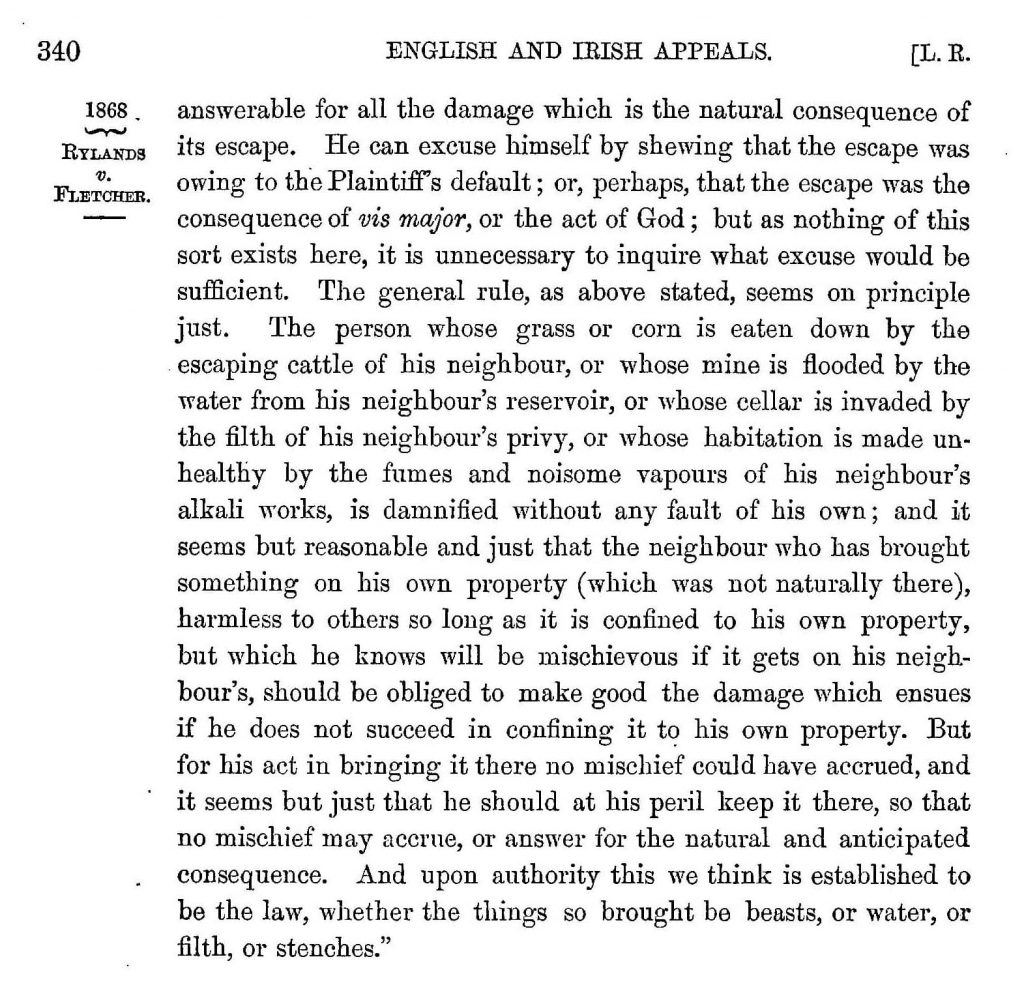

But English tort law had undergone a major revision in the 20 years before the flood. In the 1868 case Rylands v. Fletcher,[22]3 H.L. 1 (1868). This case is found in HeinOnline’s Selden Society Publications. the House of Lords ruled in favor of Thomas Fletcher, whose mine had been flooded when his neighbor, Rylands, hired contractors to build a reservoir. The contractors did not perform their work properly, and when Rylands’ reservoir was filled, it burst and flooded Fletcher’s mine.

Fletcher’s suits were initially unsuccessful, with the courts finding that since it was the contractors’ poor work, and not Ryland’s, that had caused the flood, Rylands could not be held liable. The Court of the Exchequer, however, ruled in Fletcher’s favor, with Mr. Justice Colin Blackburn finding, “the person who has brought on his land and kept there something dangerous, and failed to keep it in, is responsible for all the natural consequences of its escape.”[23]3 H.L. 1 (1868). This case is found in HeinOnline’s Selden Society Publications. The House of Lords concurred and Rylands ushered in a new era of tort law.

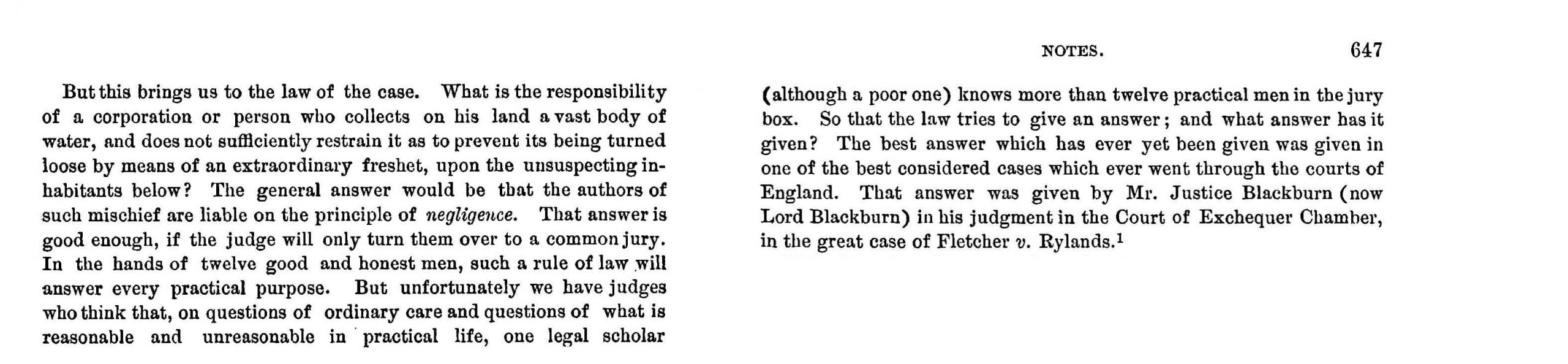

But American courts were slow to adopt the Rylands precedent, and at the time of the Johnstown flood, some American courts had recognized Rylands and others had denied it. Two months after the Johnstown flood, an article appeared in the prestigious American Law Review,[24]The entire archive of this journal can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. foreseeing the difficulties survivors would have winning justice.[25]23 AM. L. REV. 610 (1889). This article is found in in the then-current American legal system. HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

Ultimately, no suits[26]Jed Handelsman Shugerman, The Floodgates of Strict Liability: Bursting Reservoirs and the Adoption of Fletcher v. Rylands in the Guided Age, 110 YALE L.J. 333 (2000). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. against the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club or its wealthy members over the Johnstown flood were successful. The club, and the legal system that protected it, however, were convicted in the court of public opinion. In the years after the Johnstown flood, courts’ attitudes towards big industry and liability shifted away from fault-based liability towards a pro-Rylands, strict liability stance.[27]Jed Handelsman Shugerman, A Watershed Moment: Reversals of Tort Theory in the Nineteenth Century, 2 J. TORT L. [ii] (2008). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

History’s Home Is HeinOnline

Here at the HeinOnline Blog, we love showcasing history using primary and secondary documents that bring the past alive and show how it continues to inform on the present. Want more posts like this? Check out the “History” tag on the blog for more posts just like this one. And be sure to subscribe to the blog to make sure you never miss a post!

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1, ↑5, ↑9, ↑10, ↑12, ↑14 | Lawrence M. Friedman & Joseph Thompson, Total Disaster and Total Justice: Responses to Man-Made Tragedy, 53 DEPAUL L. REV. 251 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑3, ↑4 | H. Rep. 970, at 6 (1963). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑6 | Edward Dies. Behind the Wall Street Curtain (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Taxation & Economic Reform in America. |

| ↑7, ↑16, ↑18, ↑27 | Jed Handelsman Shugerman, A Watershed Moment: Reversals of Tort Theory in the Nineteenth Century, 2 J. TORT L. [ii] (2008). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑8, ↑11, ↑15 | S. Rep. No. 108-276 (2004). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑13, ↑19, ↑20, ↑26 | Jed Handelsman Shugerman, The Floodgates of Strict Liability: Bursting Reservoirs and the Adoption of Fletcher v. Rylands in the Guided Age, 110 YALE L.J. 333 (2000). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑17 | Clara Barton. Red Cross: A History of This Remarkable International Movement in the Interest of Humanity (1898). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑21 | Jed Handelsman Shugerman, The Twist of Long Terms: Judicial Elections, Role Fidelity, and American Tort Law, 98 GEO. L.J. 1349 (2010). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑22, ↑23 | 3 H.L. 1 (1868). This case is found in HeinOnline’s Selden Society Publications. |

| ↑24 | The entire archive of this journal can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑25 | 23 AM. L. REV. 610 (1889). This article is found in in the then-current American legal system. HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |