Imagine: a quiet, desolate land where ice, whipping winds, and brutally cold temperatures keep away human civilization. No homes, no businesses, no schools, no militaries. Just the hardiest species can thrive in this environment—penguins, seals, whales, maybe some seabirds. And it’s not owned by anyone.

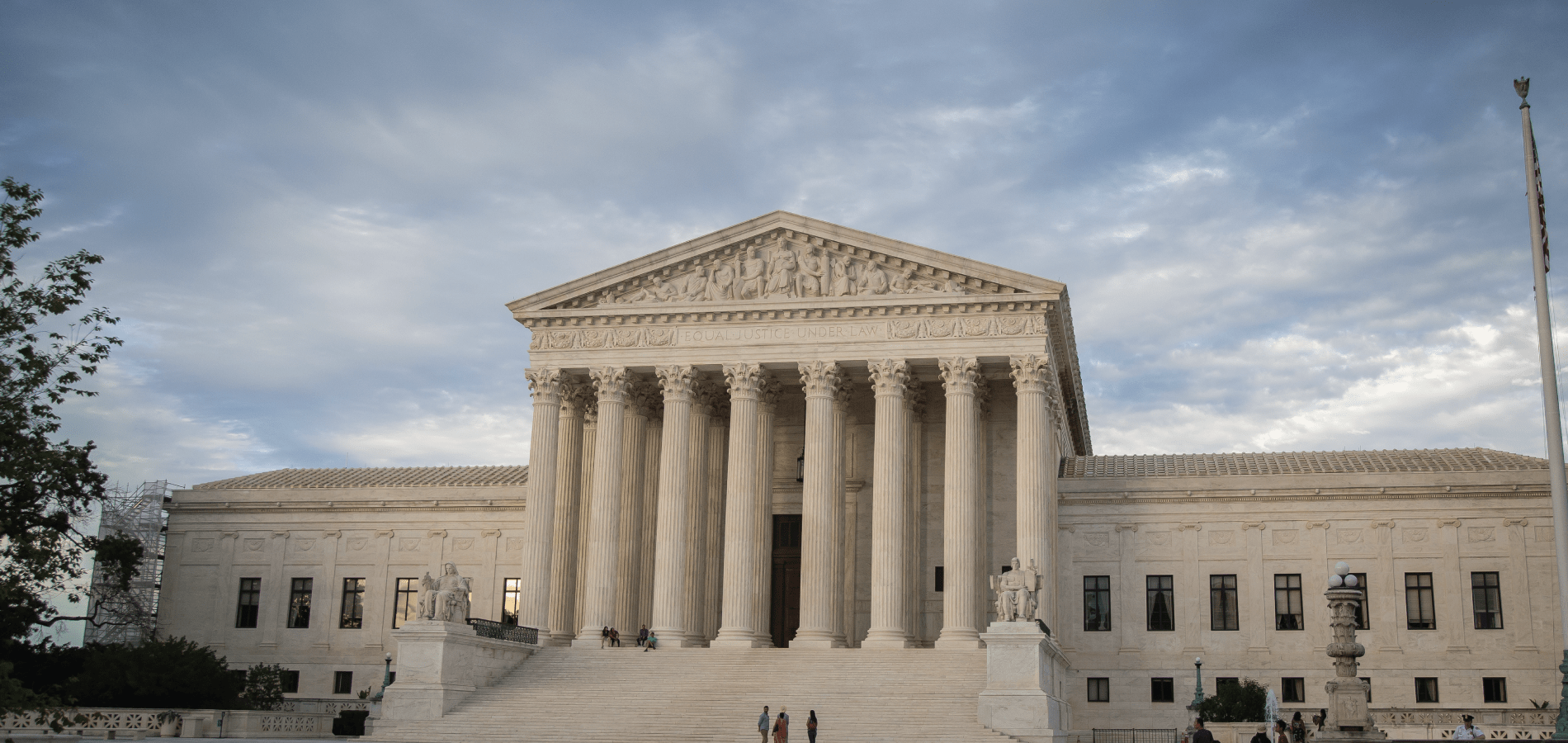

But Antarctica isn’t a complete no man’s land, and that’s because of the Antarctic Treaty, a unique and highly impactful agreement amongst various nations to keep Antarctica a peaceful refuge for scientific exploration and discovery. And, of course, it’s included in HeinOnline’s World Treaty Library. So let’s dive in and explore how this remarkable treaty came to be, and the impact it has had on keeping Antarctica a frozen wilderness.

Tensions Begin

In August 1946, the United States Navy sent 13 ships, more than 4,500 men, and aircraft to Antarctica for training purposes—in the case that there was ever a war in Antarctica, or in similar climates in the Arctic, military forces needed to be ready to contend with brutal weather conditions. Additionally, the expedition, called Operation Highjump[1]Ronald W. Scott, Protecting United States Interests in Antarctica, 26 SAN DIEGO L. REV. 575 (1989). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. assessed the feasibility of potentially building bases in the region. The following year, the U.S. conducted a similar, smaller expedition, called Operation Windmill.

In 1948, with fears about the Cold War spreading to Antarctica, the U.S. proposed that the United Nations maintain guardianship of Antarctica, but this plan was rejected. Worried that establishing any territorial claims on the continent would inspire the U.S.S.R. to stake a claim there too, America resisted, although it was itching to own land there.

In 1949, Britain, Argentina, and Chile signed the Tripartite Naval Declaration[2]Antarctic Region, 2 Dig. Int’l L. 1232 (1963). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Foreign & International Law Resources database. in which they agreed to not send any warships to Antarctica, defined as anywhere south of the 60th parallel. However, the agreement was swiftly broken. The Argentine military fired warning shots at a group of British surveyors on Hope Bay[3]Frank G. Klotz. America on the Ice: Antarctic Policy Issues (1990). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Foreign Relations of the United States database. in February 1952, prompting Britain to send a warship down there to prevent further escalation. Another skirmish soon erupted between the two nations on Antarctica’s Deception Island in early 1953. The United Kingdom filed lawsuits against Argentina and Chile with the International Court of Justice for the nations’ sovereignty claims in the area, but the cases were eventually closed.

International Geophysical Year

The International Geophysical Year (IGY)[4]“International Geophysical Year, the Arctic and Antarctica.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1958, pp. I-182. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset22584&i=403. This document can be found in … Continue reading was an international scientific project scheduled from July 1, 1957 through December 31, 1958 to correspond with peak solar activity. During this period, scientists conducted research on meteorology, oceanography, seismology, astronomy, geomagnetism, and more. Sixty-six countries participated, and a Special Committee for Antarctic Research was established, and multiple countries set up scientific research stations in Antarctica with agreements to take them down at the end of the IGY.

However, soon in 1958, America proposed extending their Antarctic research, and the U.S.S.R. agreed that they too would keep their stations up past the end of the year. With fears of the escalating Cold War reaching the coldest place on earth, President Eisenhower called for an Antarctic Conference[5]John Hanessian, The Antarctic Treaty 1959, 9 INT’l & COMP. L.Q. 436 (1960). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. consisting of the 12 countries which had more than 55 active research stations on the continent to sign a peace treaty. Representatives met in 60 sessions over a span of one and a half years, but no agreement was reached until a second conference was held in October 1959[6]Conference Documents: The Antarctic Treaty and Related Papers (1960). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Treaty Library., at which the Antarctic Treaty was finally signed.

Treaty Details

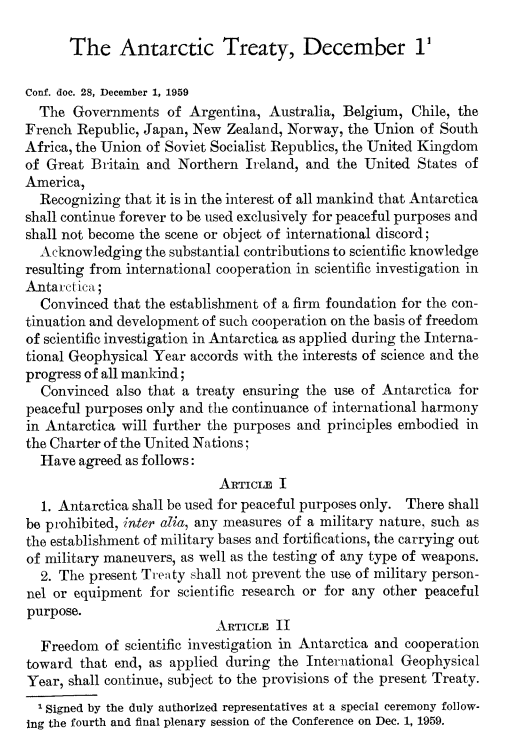

As far as treaties go, the Antarctic Treaty[7]Conference Documents: The Antarctic Treaty and Related Papers (1960). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Treaty Library. is pretty short and simple, but it has several important provisions. First and foremost is that Antarctica is to only be used for peaceful purposes—no military operations, nuclear testing, or territorial claims are allowed on the continent. Secondly, the region is to be used for science, with all scientific research derived from Antarctica to be made freely available to everyone. Therefore, the only permanent structures allowed in Antarctica are research stations.

The treaty was signed on December 1, 1959 by the following 12 countries:

- Argentina

- Australia

- Belgium

- Chile

- France

- Japan

- New Zealand

- Norway

- South Africa

- United Kingdom

- United States

- U.S.S.R.

The treaty went into force in 1961. Since 1959, 45 other countries have acceded to the Treaty.

The spirit of cooperation and mutual understanding, which the 12 nations and their delegations exhibited in drafting a Treaty of this importance, should be an inspiring example of what can be accomplished by international cooperation in the field of science and in the pursuit of peace.

Peace on the Bottom of the Earth

The Antarctic Treaty still holds today. Every 30 years, any of the consultative parties to the treaty can request revisions, but so far the treaty has only been expanded —for example, in 1991-1992, the Madrid Protocol on Environmental Protection[8]Harlan K. Cohen, Editor. Handbook of the Antarctic Treaty System (9). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Treaties and Agreements Library. was added, which prohibits any mining or oil exploration for 50 years. Other important agreements regarding Antarctica include the Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora,[9]Antarctica (measures in furtherance of principles and objectives of the Antarctic Treaty), 17 U.S.T. 991 (1964). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Treaties and Agreements Library. as well as the United States’ Antarctic Conservation Act,[10]To implement the Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora, and for other purposes., Public Law 95-541, 95 Congress. 92 Stat. 2048 (1978). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. which prohibits taking of any native mammals or birds, introduction of non-indigenous species, and polluting the lands or waters of Antarctica.

Today, there are 57 parties included in the Antarctic Treaty, which represent about two-thirds of the total world population. Each year, Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings are held amongst the 29 decision-making consultative parties of the treaty, along with any other parties who wish to join. The Antarctic Treaty Secretariat, which enforces the treaty, is headquartered in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

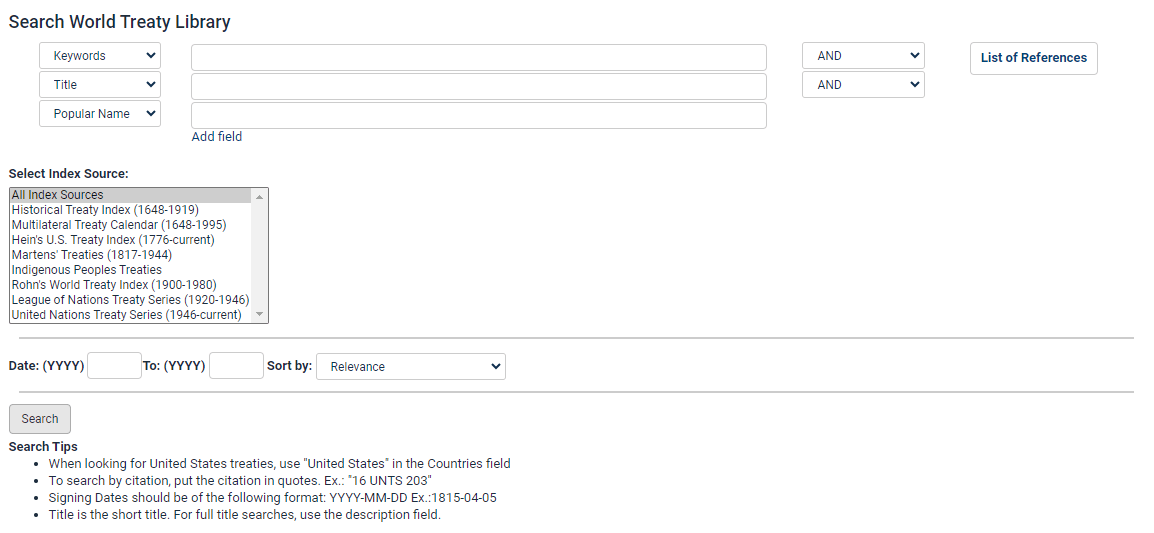

Continue Your Treaty Research in HeinOnline

HeinOnline’s World Treaty Library is a monumental database that brings together works from Rohn, Dumont, Wiktor, and Martens to create the richest collection of world treaties ever available, spanning from 1648 to the present. It includes more than 1,200 titles and 3.6 million pages of treaties that have shaped our world today, and in true HeinOnline fashion, it contains in-depth indexing, including a Treaty Index Search Tool, as well as cross-citation linking to allow users to easily locate treaties.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Ronald W. Scott, Protecting United States Interests in Antarctica, 26 SAN DIEGO L. REV. 575 (1989). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Antarctic Region, 2 Dig. Int’l L. 1232 (1963). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Foreign & International Law Resources database. |

| ↑3 | Frank G. Klotz. America on the Ice: Antarctic Policy Issues (1990). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Foreign Relations of the United States database. |

| ↑4 | “International Geophysical Year, the Arctic and Antarctica.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1958, pp. I-182. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset22584&i=403. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑5 | John Hanessian, The Antarctic Treaty 1959, 9 INT’l & COMP. L.Q. 436 (1960). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑6 | Conference Documents: The Antarctic Treaty and Related Papers (1960). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Treaty Library. |

| ↑7 | Conference Documents: The Antarctic Treaty and Related Papers (1960). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Treaty Library. |

| ↑8 | Harlan K. Cohen, Editor. Handbook of the Antarctic Treaty System (9). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Treaties and Agreements Library. |

| ↑9 | Antarctica (measures in furtherance of principles and objectives of the Antarctic Treaty), 17 U.S.T. 991 (1964). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Treaties and Agreements Library. |

| ↑10 | To implement the Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora, and for other purposes., Public Law 95-541, 95 Congress. 92 Stat. 2048 (1978). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |