Happiness is a warm puppy, according to Peanuts creator Charles Schultz. But for many people, dogs are more than a source of happiness, companionship, and love: they are vital lifelines to the outside world. Service animals, including guide dogs, hearing dogs, and seizure response dogs, are defined by Titles II and III of the Americans with Disabilities Act, but animals have performed these functions long before being codified in the Act. Since the formal introduction of guide dogs into American life in the 1930s, the public at large has become accustomed to seeing harnessed and vest-wearing dogs out in public spaces with their handlers, whether it be the traditional guide dog to “new” emotional support animals. But recently, fueled by stories of emotional support peacocks and emotional support squirrels attempting to board planes, debate over the propriety of these animals has increased. Using HeinOnline, let’s chew over the various sides of this issue and explore the remarkable history of service animals.

Don’t be left out in the doghouse. Make sure you’re subscribed to the following databases to follow along.

- Federal Register

- Law Journal Library

- United States Code

- U.S. Congressional Serial Set

- U.S. Statutes At Large

Guiding Eyes after War

For centuries a special relationship has been documented between the dog devoted to a blind person. The story of the modern guide dog, however, begins after World War I, when the first guide dog schools were opened in Germany to train German Shepherd Dogs to assist blinded veterans. One of these schools attracted the attention of Dorothy Harrison Eustis, a wealthy American living in Switzerland where she trained German Shepherd Dogs for police and military work. After studying one of these guide dog schools, she wrote an article publicizing its work. In 1927, that article was published in The Saturday Evening Post, where it came to the attention of Morris Frank, a blind man, and he wrote to Eustis about the possibility of receiving one of these amazing German dogs. While not a guide dog trainer, Eustis took Frank up on his request. She brought Frank to Switzerland to train with a German Shepherd named Buddy, who would become America’s first official seeing-eye dog. Together, Eustis and Frank brought formally trained guide dogs into the wider American conscience, and founded a guide dog organization called The Seeing Eye in 1929, which still operates today.

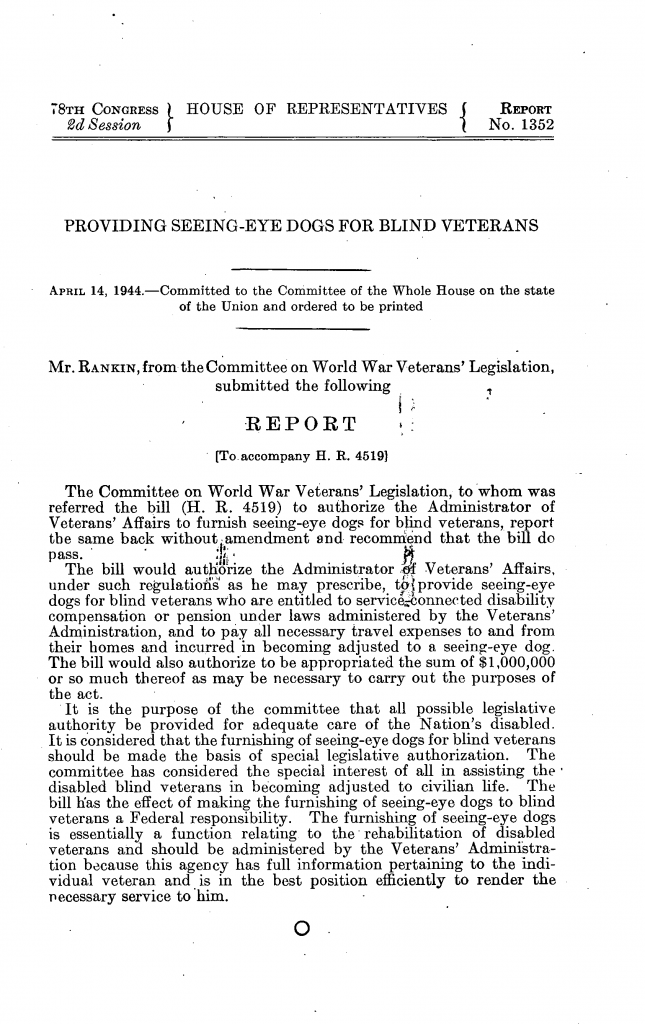

Dogs like Buddy and their handlers faced difficulties integrating fully into American society, especially in public transportation. To try and correct the problem of guide dogs being barred from subways, buses, street cars, and other modes of public transportation, in 1937 Congress amended the Interstate Commerce Act to allow guide dogs to travel with their handlers without paying an extra fare. Despite this amendment, guide dogs and their handlers still faced obstacles in public transportation even as society, and Congress, realized the usefulness of guide dogs, authorizing the Veterans’ Administration to provide blinded veterans with guide dogs as part of their disability compensation. As more and more guide dogs were paired with handlers, the potential of specially trained dogs to enrich the lives of disabled persons led to dogs being trained to provide other functions, with hearing dogs and mobility dogs became more commonplace in the 1970s and 1980s.

A Difference of Definitions

The Americans with Disabilities Act

The most consequential federal legislation affecting the lives of disabled persons in the United States is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), passed in 1990. Taking its structure from the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the five titles of the ADA prohibit discrimination in employment and public life against Americans with physical and mental disabilities. The original text of the ADA provided the first federal definition of a service animal, but its definition was broad, defining them as “any guide dog, signal dog, or other animal individually trained to do work or perform tasks for the benefit of an individual with a disability.” An updated definition came in 2010, and the current legal definition of a service animal under the ADA is “any dog that is individually trained to do work or perform tasks for the benefit of an individual with a disability, including a physical, sensory, psychiatric, intellectual, or other mental disability.”

The final rule further clarifies that a service animal must be under the handler’s control at all times by “a harness, leash, or other tether, unless either the handler is unable because of a disability to use a harness, leash, or other tether, or the use of a harness, leash, or other tether would interfere with the service animal’s safe, effective performance of work or tasks, in which case the service animal must be otherwise under the handler’s control (e.g. voice control, signals, or other effective means).” It does not require the service animal to wear any specific vest, harness, or tag declaring it a service animal and does not set any breed requirements. Finally, the Act does not require any type of formal training requirements or certification for the service animal, relying instead on the work performed by the animal and its composure and behavior in public to suffice as evidence of its training. The Act makes one exception to its narrow definition of a service animal as a dog, allowing miniature horses to be used instead of a dog. It specifically excludes emotional support animals (ESAs) from its definition of a service animal, finding that while an ESA can certainly be comforting to a handler, “the presence of such animals is not required in the context of public accommodations, such as restaurants, hospitals, hotels, retail establishments, and assembly areas.” Under the ADA, tasks or work performed, such as leading a blind person, picking up objects or opening doors for the mobility impaired, or alerting an epileptic handler of an impending seizure, is paramount in its criteria for a service animal.

The Air Carrier Access Act

But the ADA is not the only federal law that weighs in on service animals. Air travel is governed by the Air Carrier Access Act of 1986 (ACAA), whose most recent guidelines adopt the ADA’s definition of a service animal as “a dog, regardless of breed or type, that is individually trained to do work or perform tasks for the benefit of a qualified individual with a disability.” Unlike the ADA, the ADAA does not recognize miniature horses as service animals, restricting that definition to dogs only. Airlines can require handlers to submit forms from the Department of Transportation that attest to the animal’s training, good behavior, and that it will not relieve itself on a long flight or can do so in a sanitary manner. While a carrier cannot deny a service animal because of its breed, it can require that the animal fit in the handler’s lap or foot space on the aircraft, potentially excluding dogs such as mastiffs or Great Danes. Finally, no doubt in response to stories such as peacocks and squirrels flying as emotional support animals, as of 2021 the final rule of the ACAA excludes “all non-task-trained animals, such as emotional support animals, comfort animals, and service animals in training” from its definition of a service animal. The Department of Transportation allows airlines to treat emotional support animals as pets, meaning that, unlike service animals, they can be charged to fly (or denied access altogether); airlines may, at their own discretion, decide to transport emotional support animals without charge, but they are not legally required to do so.

To help carriers determine if an animal is a service animal, carriers are legally allowed to ask if the animal is required to accompany the passenger because of a disability and what work or task the animal has been trained to perform, but they cannot inquire about the nature or extent of a person’s disability or ask for the animal to demonstrate its work or task. Carriers can also use judgment on observing an animal’s behavior to make an assessment on its training, or use the aid of identifying harnesses or tags, although these are not required to board a plane.

Fair Housing Act

Further complicating all this is the Fair Housing Act (FHA). While both the ADA and the ADAA adopt similar definitions of a service animal and make legal distinctions between service animals and emotional support animals, the FHA recognizes emotional support animals in ways the other two laws do not. Adopting the broader term of “assistance animals” rather than service animals, it defines these animals as “an animal that works, provides assistance, or performs tasks for the benefit of a person with a disability, or provides emotional support that alleviates one or more identified symptoms or effects of a person’s disability.” It also notes that with such a distinct difference between the private space governed by the FHA and the public spaces under the purview of the ADA and ADAA, including emotional support animals in these spaces is warranted, stating that “emotional support animals by their very nature, and without training, may relieve depression and anxiety.”

Adding to the confusion, the ADA can be preempted by state and local laws that grant greater protections to individuals with disabilities, resulting in service animal laws that can vary both from state to state and from federal law. Thirty-one states also currently have laws that criminalize service animal fraud. But on the other side of this debate, a debate exacerbated no doubt by differing and conflicting federal definitions, are arguments in favor of officially recognizing emotional support animals and the very real function they can serve, such as those demonstrated in animal-assisted therapy. Exacerbating the debate is the relative ease with which anyone, with a simple Google search, can obtain “documentation” attesting that their pet is an emotional support animal, combined with a reported increase from psychologists of patients asking to be certified as needing an emotional support animal. Advocates of emotional support animals argue that bringing them under the ADA’s definition of a service animal would help address these fraudulent animals and also eliminate a hierarchy of assistance created by distinguishing between those whose disabilities grant them an animal in public spaces and those whose disabilities do not. Creating a uniform certification process for emotional support animals could also help distinguish between masquerading pets and legitimate working dogs, documentation that is not currently required under the ADA for service animals, although a counterargument to certification is the barrier it could erect for obtaining service animals, an already expensive process. Confusion over whether a service animal is legitimate has led to ADA-protected service dogs being denied access because of establishments’ previous bad encounters with fraudulent service dogs, although, as Rebecca J. Huss phrased it, “[g]iven that persons with apparent disabilities using guide dogs continue to have issues gaining access to public accommodations, perhaps our society is not ready to truly accept the premise of the ADA, that all types of disabilities should be accommodated.”

Sit. Stay. Subscribe.

Whether you’re a dog or a cat person, the HeinOnline blog has a post to interest researchers of all stripes. Whether its research tips and tricks, exploring history’s mysteries, or looking at a topic a little more timely, you can ensure you’ll never miss a post by subscribing below. We’ll fetch new posts and deliver them straight to your inbox (and won’t beg for a Milkbone in return).