It’s no secret that American history is full of heinous acts committed by white settlers against the indigenous peoples who populated North America centuries before Christopher Columbus was even born. From Indian relocation and the Trail of Tears to various wars and battles, unknown numbers of indigenous people perished at the hands of Americans seeking to achieve manifest destiny, expanding from Atlantic to Pacific and driving the native peoples out with it. One such example is the Battle of Wounded Knee, which is now widely referred to as the Wounded Knee Massacre to acknowledge the gunning down of more than 150 indigenous people, including women and children. Let’s dive into the tragedy in this month’s Secret of the Serial Set.

Setting the Scene

Throughout the 19th century, native peoples across America reckoned with the loss of their land to the American government and were confined to federal-owned reservation territory. The Lakota peoples of the Northern Plains especially struggled, as the bison that once roamed the prairies and provided their communities with food, clothing, and livelihood neared extinction.[1]“Protection of American bison and other animals.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1889, pp. 1-2. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset33586&i=723. This document can be found in … Continue reading At the same time, the federal government was breaking their treaty promises by continuing to take away land. A drought brought poor harvests. Diseases such as flu, measles, and whooping cough ripped through the reservations. The government had prohibited the sacred native Sun Dance[2]“Annual report of Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1883.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1883, pp. 1-376. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset25412&i=106. This document can be found in … Continue reading religious ceremony. The Dawes Act[3]Chapter 119, 49 Congress. 24 Stat. 388 (1883-1887) (1887). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. of 1887 was slated to strip the Lakota of even more land. The tribe had lost virtually everything—and they were understandably desperate for any semblance of hope.

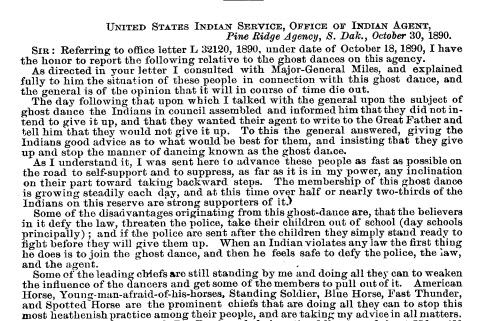

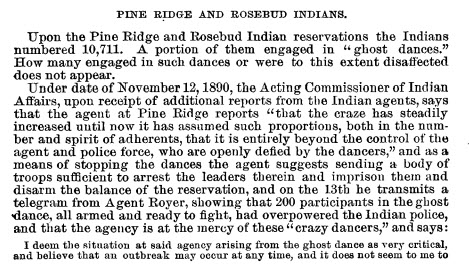

Enter the Ghost Dance,[4]“Alleged armament of Indians in certain States.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1890, pp. 1-52. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset33592&i=224. This document can be found in … Continue reading a religious movement that formed around 1870 and was brought to the Lakota in 1889 by the prophet Wovoka.[5]Edward H. Spicer. Cycles of Conquest: The Impact of Spain, Mexico, and the United States on the Indians of the Southwest, 1533-1960 (1962). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, … Continue reading The movement was based on the belief that native peoples were suffering because they had angered the Creator by abandoning their traditional customs. By participating in the Ghost Dance, utopia could be restored, bringing a return to land, crops, the bison, and even the deceased, while wiping out the white people who had stolen everything from them. In addition, the white muslin shirts worn during the Ghost Dance were believed to offer sacred protection from harm—even from bullets.[6]William Christie Macleod. American Indian Frontier (1928). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law database. By the time winter came around in 1890, an estimated one-third of the Lakota peoples were participating in the Ghost Dance.

However, it was not a movement understood by American settlers, who saw the dance as ominous and a foreshadowing of an armed uprising.[7]“Summary of relations between U.S. and Sioux and Cheyenne nations at Standing Rock, Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations for purpose of adjudication of Indian depredation claims; events leading to massacre of Wounded Knee, … Continue reading

The Army Steps In

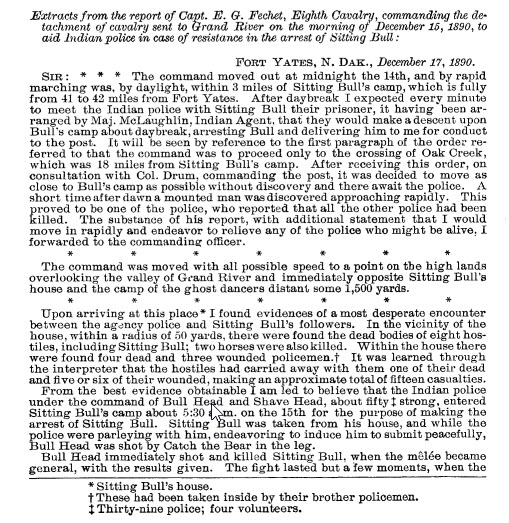

In response, the federal government banned the Ghost Dance and sent out part of the United States Army 7th Cavalry—which had suffered a significant loss at the Battle of the Little Bighorn 14 years earlier, including the death of revered Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer—with orders to arrest tribal leaders promoting the Ghost Dance. Indian police, who falsely believed that Chief Sitting Bull was a Ghost Dance leader, attempted to arrest him at Standing Rock reservation[8]“Granting pensions and medals to Indians of Standing Rock Agency who arrested Sitting Bull.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1891, pp. 1-12. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset33238&i=22. … Continue reading in northeast South Dakota, resulting in a skirmish with several of his followers that ended with Sitting Bull receiving fatal bullet wounds to the head and chest.

Following Sitting Bull’s death, his half-brother Chief Big Foot proceeded to flee Standing Rock with a group of other Lakota members, heading toward Pine Ridge Reservation, on the other side of the state. The 7th Cavalry soon caught up with the Lakota near Wounded Knee Creek, where they arrested a severely ill Big Foot[9]“Annual Report of the Secretary of War, 1891, v.1.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1891, pp. 1-908. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset33259&i=174. This document can be found in … Continue reading and surrounded the Lakota camp with their four Hotchkiss mountain guns.[10]“Liquidating liability of United States for massacre of Sioux Indians at Wounded Knee, Dec. 29, 1890.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1940, pp. 1-14. HeinOnline, … Continue reading

The Massacre

On December 29, 1890, U.S. soldiers invaded the Lakota camp and seized their weapons. Accounts vary as to exactly what happened, but the most common theory is that as a soldier was attempting to wrestle a weapon out of a deaf Lakota man’s hands, an accidental gun shot went off. Immediately, soldiers began firing at the Lakota, the majority of which were now unarmed. By the end of the massacre, at least 150 Lakota had been killed, two-thirds of whom were women and children.

The Aftermath

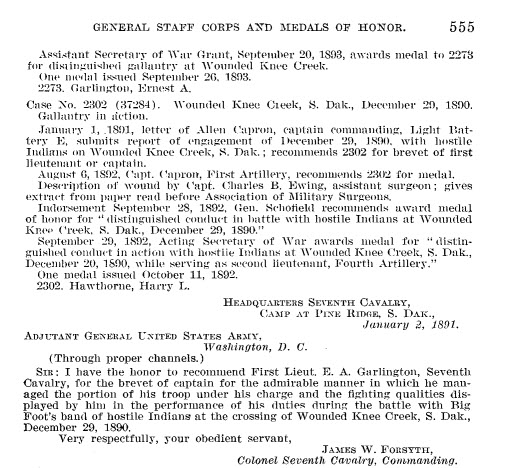

The dead were later buried in a mass grave. Many survivors were imprisoned and later sent to perform as part of Buffalo Bill’s[11]“Affairs of Indians at Pine Ridge and Rosebud agencies.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1891, pp. 1-186. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset33237&i=389. This document can be found in … Continue reading Wild West Show. After the massacre, 20 members of the 7th Cavalry were awarded Medals of Honor—activists continue to request that these honors be rescinded. The Wounded Knee battlefield has since been designated a National Historic Landmark, and in 1990, Congress passed a formal resolution on the 100th anniversary of the massacre to express “deep regret.”[12]136 Cong. Rec. S15221 (1990). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database.

Help Us Complete the Project

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Documents from additional HeinOnline databases have been incorporated to supplement research materials for non-U.S. related events discussed.

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us, please contact Steve Roses at 716-882-2600 or sroses@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give special thanks to all of the libraries that have provided generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

Continue Your Research with Our Indigenous Peoples of the Americas Database

HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law database is an expansive archive of materials related to indigenous American life and law, including hundreds of treaties, tribal codes, constitutions, treaty-related publications, and more. Containing nearly 4,000 titles and more than 2.3 million pages, this collection shares the tremendous influence that indigenous peoples and their cultures have had on the development of the United States of America.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | “Protection of American bison and other animals.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1889, pp. 1-2. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset33586&i=723. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Annual report of Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1883.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1883, pp. 1-376. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset25412&i=106. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑3 | Chapter 119, 49 Congress. 24 Stat. 388 (1883-1887) (1887). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑4 | “Alleged armament of Indians in certain States.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1890, pp. 1-52. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset33592&i=224. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑5 | Edward H. Spicer. Cycles of Conquest: The Impact of Spain, Mexico, and the United States on the Indians of the Southwest, 1533-1960 (1962). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law database. |

| ↑6 | William Christie Macleod. American Indian Frontier (1928). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law database. |

| ↑7 | “Summary of relations between U.S. and Sioux and Cheyenne nations at Standing Rock, Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations for purpose of adjudication of Indian depredation claims; events leading to massacre of Wounded Knee, 1890-91.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1898, pp. 1-8. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset32673&i=459. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑8 | “Granting pensions and medals to Indians of Standing Rock Agency who arrested Sitting Bull.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1891, pp. 1-12. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset33238&i=22. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑9 | “Annual Report of the Secretary of War, 1891, v.1.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1891, pp. 1-908. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset33259&i=174. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑10 | “Liquidating liability of United States for massacre of Sioux Indians at Wounded Knee, Dec. 29, 1890.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1940, pp. 1-14. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset23265&i=1416. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑11 | “Affairs of Indians at Pine Ridge and Rosebud agencies.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1891, pp. 1-186. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset33237&i=389. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑12 | 136 Cong. Rec. S15221 (1990). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |