This past Tuesday, the Affordable Care Act returned to the Supreme Court for the third time. Opponents argue that the health insurance mandate included in the legislation is unconstitutional, and that the entire act should therefore be struck down.

You may be wondering, from where does the Supreme Court derive this power? To discover the answer, travel with HeinOnline back to the turn of the nineteenth century.

The Election of 1800

This story starts with a presidential election, which, we have to say, is a much more enjoyable phenomenon to look back on than to experience. The main candidates were incumbent President John Adams—a Federalist favoring strong central government—and Vice President Thomas Jefferson, founder of the Democratic-Republican party and a proponent of decentralization and increased power to state governments.

During his presidency, Adams had attempted to seek peaceful relations with France, which had begun attacking American ships following the ratification of the Jay Treaty. Proper negotiations failed when the French foreign minister demanded bribes, offending the American diplomats and ultimately enraging the American public at home. The tension led to what’s become known as the Quasi-War, an unofficial naval war between France and the United States. The Adams administration and Federalist-controlled Congress expanded the navy in preparation, while also strengthening national security through the Alien and Sedition Acts—four laws that restricted immigration and criminalized criticism of the American federal government.

Led by Jefferson, Democratic-Republicans decried the new legislation and also attacked the Federalists for their imposition of heavy taxes. The nation became increasingly polarized, and the Federalist Party fractured under growing tension between party leaders Adams and Alexander Hamilton. The Democratic-Republicans’ well-organized campaign, in contrast to the instability of the Federalists, ultimately won them the presidency. With help in the House from Hamilton himself, Thomas Jefferson became the overall Democratic-Republican winner.

The Midnight Judges

The election made history as the first time power would be transferred between opposing political parties. As we well know these days, such transfers are not always peaceful. Despite the bitterness between their campaigns, however, the presidency did pass from Adams to Jefferson with relative ease … for the most part.

In a display of pettiness that one almost can’t help but admire, John Adams spent his last two days as President appointing nearly 60 members of his party to new circuit judge and lifelong justice of the peace positions. The positions had recently been created with the passage of the Judiciary Act of 1801, intended to increase judiciary efficiency by reorganizing the Supreme Court, circuit courts, and district courts. The Federalist-controlled Senate quickly confirmed Adams’ last minute nominees. Secretary of State John Marshall—remember his name, he’ll be back later—facilitated the delivery of as many of the judges’ commissions as possible, right up until the day of Jefferson’s inauguration.

Unfortunately for the Federalists, when that day came, not all of the commissions for these “Midnight Judges” had been delivered. And as Thomas Jefferson so matter-of-factly states in the hit musical Hamilton, every action has its equal, opposite reaction. Now the one with the power, Jefferson ordered his new Secretary of State, James Madison, to withhold the remaining commissions. Without their commissions, these remaining appointees would be unable to assume their offices.

Marbury v. Madison

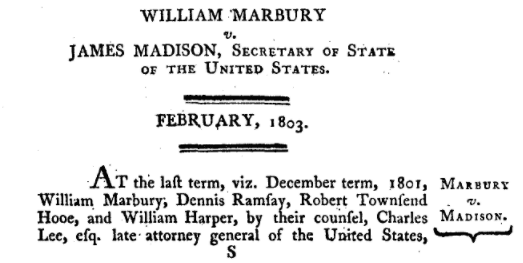

William Marbury, one of the men whose commission was not delivered in time, was particularly unhappy about the situation. Madison repeatedly denied Marbury his commission and, in response, Marbury filed a lawsuit directly with the Supreme Court, asking them for a writ of mandamus that would force Madison to deliver his commission. Perhaps in retaliation for Adams’ appointment of the “midnight judges,” Democratic-Republicans in Congress pushed through a bill that would cancel the Supreme Court’s 1802 term. All pending cases, including Marbury’s, were postponed a year, so Marbury v. Madison was not heard until 1803.

When it did reach the Court, the presiding Chief Justice was none other than staunch Federalist John Marshall. Remember him? He was the one who, as former Secretary of State, had originally facilitated the delivery of the commissions. Come 1803, Marshall was in a serious political quandary—ruling in favor of Madison would obviously have given Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans a political victory. However, a ruling in favor of Marbury (ordering Madison to deliver the commission) would likely have been ignored by the Jefferson administration. That possibility risked making the relatively young Supreme Court appear weak or ineffective.

Marshall began addressing the dilemma by asking three questions:

- Did Marbury have a right to his commission?

- If yes, was there a legal remedy for him to obtain his commission?

- If yes, could the Supreme Court legally issue that remedy?

Question One: Marbury’s Right

After digging into the details surrounding the appointment process, Marshall found that all procedures were followed according to the letter of the law. The commissions had been signed and sealed by President John Adams, meaning that Marbury’s commission, in particular, was valid. The Court thus ruled that any withholding of his valid commission was in violation of Marbury’s vested legal right.

Question Two: Marbury’s Legal Remedy

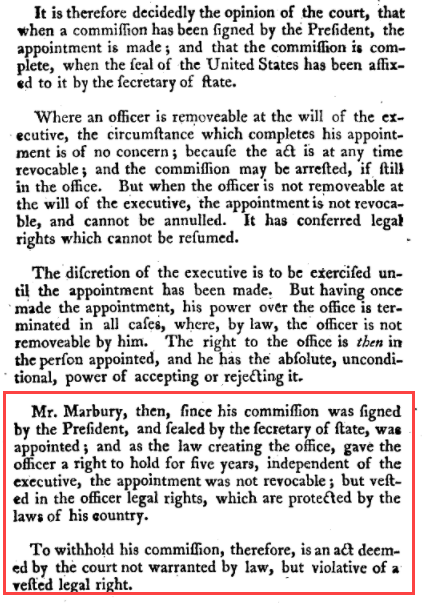

Now that it had been established that Madison violated a legal right of Marbury’s, the next question was whether Marbury had a legal remedy. In answering the question, Marshall immediately eliminated any doubt, stating “The very essence of civil liberty certainly consists in the right of every individual to claim the protection of the laws, whenever he receives an injury.”

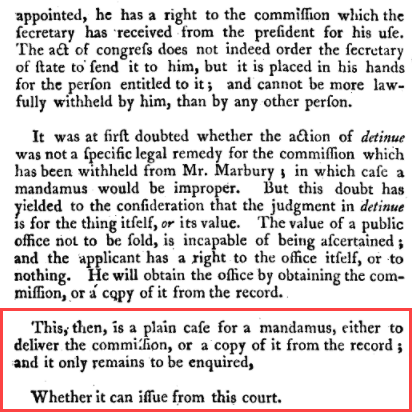

However, what exactly the legal remedy would be in this case still remained up for debate. Could the Supreme Court issue a writ of mandamus, as Marbury had requested, and force Secretary Madison to comply? Marshall argued yes, stating “It is not by the office of the person to whom the writ is directed, but the nature of the [illegal] thing to be done that the propriety or impropriety of issuing a mandamus, is to be determined.” Ultimately, Marshall wrote, “This, then, is a plain case for a mandamus, either to deliver the commission, or a copy of it from the record …”

Question Three: The Jurisdiction of the Court

Marbury had a legal right to his commission, which was violated by Madison. Marbury requested a writ of mandamus to force Madison to deliver his commission, which was the proper legal remedy. But did the Supreme Court, with whom Marbury filed his suit directly, have the proper jurisdiction and, therefore, the power to issue that writ in this case?

Marbury turned to the Judiciary Act of 1789 for his answer, legislation necessitated by the U.S. Constitution to outline the structure of the Supreme Court. Section 13 of the act states the following:

“The Supreme Court shall have jurisdiction over all cases of a civil nature where a state is a party, … And shall have exclusively all such jurisdiction of suits or proceedings against ambassadors, or other public ministers, … The Supreme Court shall also have appellate jurisdiction from the circuit courts and courts of the several states, in the cases herein after specially provided for; and shall have the power to issue … writs of mandamus, in cases warranted by the principles and usages of law, to any courts appointed, or persons holding office, under the authority of the United States.”

Original jurisdiction, referred to by “jurisdiction” in the first line, gives a court the power to hear a particular case for the first time and make the first decision. Because Marbury filed his case directly with the Court, his case was a matter of original jurisdiction. Appellate jurisdiction, however, gives a court the power to hear an appeal following another court’s decision, and to review, amend, or overrule that decision.

This section of the act clearly states that the Supreme Court has both original and appellate jurisdiction, depending on the case in question. What is not clear is whether writs of mandamus can be issued by the Court under both types of jurisdiction, or only under appellate jurisdiction. The text could be interpreted in favor of either outcome, mainly due to the ambiguous use of one single semicolon.

Ultimately, Marshall interpreted the text to mean that the Supreme Court could issue a writ of mandamus in a case under original jurisdiction, such as Marbury’s.

Establishing Judicial Review

So, it sounds like Marbury—and therefore Federalists at large—won the case, right? Wrong. Marshall went further to state that “The authority, therefore given to the Supreme Court by the act … appears not to be warranted by the constitution; and it becomes necessary to enquire whether a jurisdiction, so conferred, can be exercised.”

Yes, the Court could have issued the writ in a case under original jurisdiction. But Marbury’s case wasn’t actually original jurisdiction, according to the Constitution. According to Article III, Section 2, the Constitution states that the Supreme Court only has original jurisdiction in cases where (1) a U.S. State is a party or (2) the case involves foreign ambassadors, ministers, or consuls. Marbury’s lawsuit met neither of those criteria, so if one were to adhere to the Constitution directly, the Supreme Court should not have even heard his case at all.

Section 13 of the Judiciary Act directly conflicted with what was laid out by the Constitution, expanding the previous scope of the Court’s original jurisdiction—beyond what the framers originally specified—to include writs of mandamus. Marshall ruled that Congress could not expand upon the words of the Constitution in such a way, meaning that that section of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was actually unconstitutional.

This was the first time that the Supreme Court had ever utilized the power of judicial review, invalidating a law because of its incompatibility with the authority of the U.S. Constitution. Marshall’s opinion on this case gave federal courts the ability to “strike down” legislation based on unconstitutionality from this point forward. If you want to get really technical, however, this power of judicial review is also not outlined specifically in the Constitution, but Marshall provided numerous reasons to explain how the ability is implied by the document, and also why it is a necessary power given the structure of the U.S. government.

Thus, the particular phraseology of the constitution of the United States confirms and strengthens the principle, supposed to be essential to all written constitutions, that a law repugnant to the constitution is void; and that courts, as well as other departments, are bound by that instrument.

Given that its original ruling on Marbury’s case was now technically invalid, the Court was unable to issue Marbury’s writ of mandamus. In other words, the Court could not force Madison to deliver Marbury’s commission.

This was the genius of Marshall’s reasoning in Marbury v. Madison. The Court had initially ruled that Secretary Madison’s actions were illegal, likely making Federalists everywhere squeal with glee. But the final ruling gave Jefferson and his administration the outcome they desired, as well—Madison was not required to deliver Marbury’s commission. The cherry on top? Marshall was able to introduce judicial review, a power that he had been itching to establish for the Court. In the end, Marbury never did hold a judicial office, and Madison followed Jefferson to become the fourth president of the United States six years later.

It probably doesn’t need to be said, but history provides invaluable context for understanding current events. At the HeinOnline Blog, it’s one of our favorite subjects to write about.

Subscribe to the blog today to receive similar content right to your inbox.