Both sides agreed the war would be over by Christmas. South Carolina had seceded from the Union the previous year, on December 20, 1860, and by February six more states had also left the Union. Newly independent South Carolina demanded the U.S. Army pull out of Charleston Harbor, but instead of leaving Carolinian waters, the army relocated to Fort Sumter. A tense siege followed, ending with gunfire on April 12, 1861. Read more about the fighting at Fort Sumter in this blog post. When the artillery stopped firing the next day, the U.S. Army abandoned the fort, four more Southern states seceded to join the Confederate States of America, and the American Civil War had officially begun.

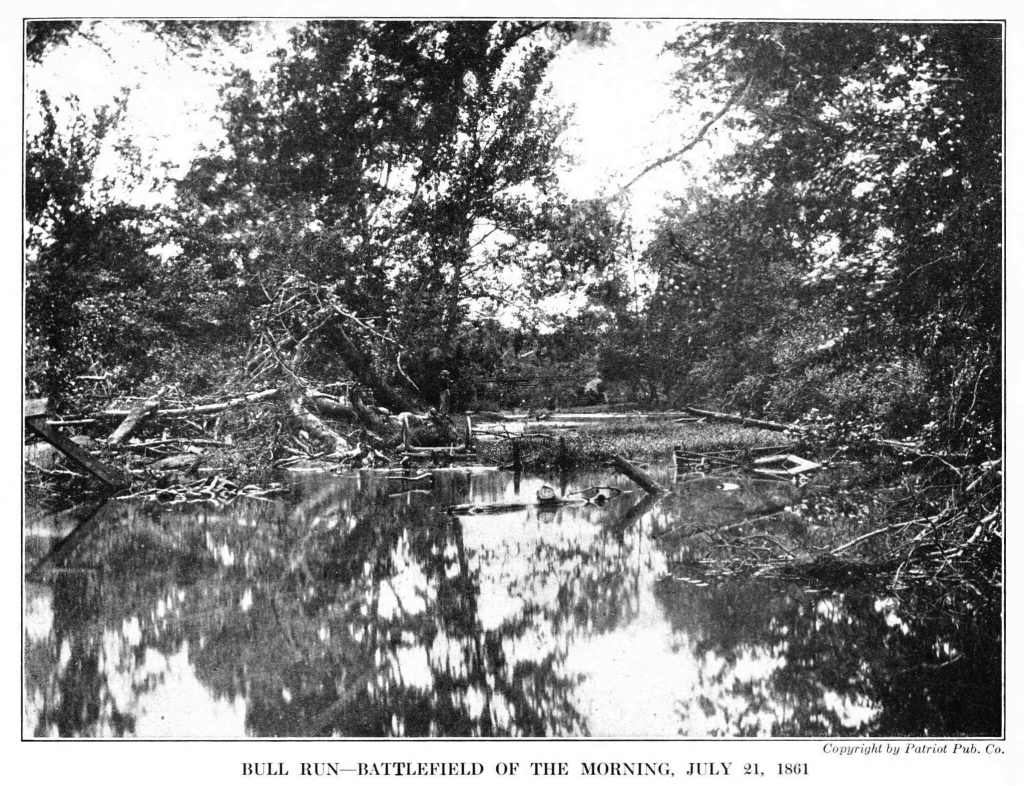

160 years ago, the first battle of this bloody war was fought near a creek running through Manassas, Virginia. The Battle of First Manassas, also known as the First Battle of Bull Run, was predicted to be the war’s first and last battle. Read on to learn more about this moment in history.

Before we begin, a note on the battle name: Union forces typically named battles after significant rivers or creeks near the fighting, while Confederate forces relied on the names of nearby towns. The Union, therefore, called the battle that is the subject of this post “The First Battle of Bull Run,” while the Confederacy used the name “The Battle of First Manassas.” Since the U.S. National Park service uses Manassas for the name of the battlefield park and the hallowed ground under its protection, it is the name that will be used in this post.

Scott and Spies

Two days after the fall of Fort Sumter, on April 15, 1861, President Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for 75,000 men to volunteer to augment the standing U.S. Army, which then numbered about 15,000 soldiers. These volunteers would be bound by an enlistment commitment of three months—certainly plenty of time for the war to come to an end. But the call for volunteers tipped additional states to secede. Rather than send their men to fight for the Union, these states—including the geographically critical Virginia, which officially voted to secede on April 17th—decided to join the Confederacy. As tensions continued to foment and the possibility of a brief war began to seem less likely, Lincoln issued another proclamation in May calling for an additional 42,034 men to volunteer to fight.

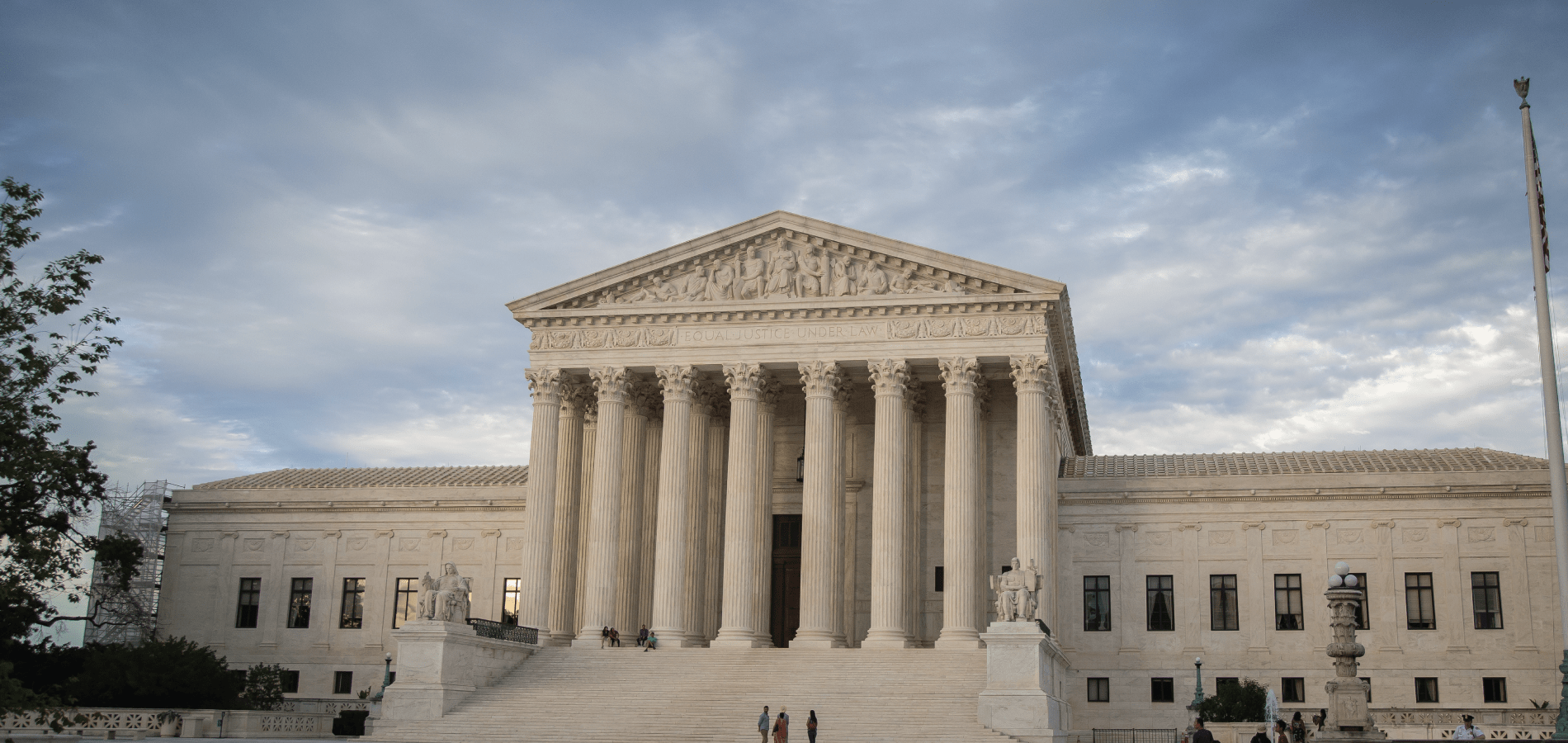

That summer, the Confederate capitol relocated from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia, approximately 100 miles south from Washington, D.C., while green Union troops drummed on the lawn of the uncompleted Washington Monument. Political fighting in the Union capitol argued about the best tactic to adopt to end the nascent war. General-in-Chief Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, a seasoned veteran of the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War, wanted to starve the Confederates out of secession; he envisioned a strategy where 80,000 troops would take command of the Mississippi River while the U.S. Navy blockaded Southern ports and the Gulf of Mexico, squeezing the Confederacy from the east and west. Known as the Anaconda Plan, the less than dramatic strategy was lambasted in Northern newspapers, which called for a direct assault on the Confederate capitol. Scott, who was seventy-five years old in 1861 and in poor health, could not physically lead the Union Army, regardless of which strategy was ultimately implemented. At the urging of Secretary of the Treasury and future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Salmon P. Chase, Major Irvin McDowell was given command of the Army of Northeastern Virginia, then the name for the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater (later called the Army of the Potomac). McDowell, a West Point graduate, had spent the majority of his army career performing various staff duties in the Adjutant General’s Office.

While McDowell had limited command experience, he was nonetheless under intense pressure to make an offensive strike, a decision made more urgent by the imminent expiration of thousands of soldiers’ ninety-day enlistments. On July 16th, McDowell ordered his men to march.

Some thirty-five miles from Washington, at the critical railroad terminus of Manassas Junction, 20,000 Confederate troops were encamped behind batteries and defensive fronts. They were under the command of Brig. Gen. Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, who had led the southern assault on Fort Sumter months earlier. Beauregard had served as an engineer under Winfield Scott during the Mexican-American War and, like his Union counterpart McDowell, was a West Point graduate. Beauregard knew of McDowell’s plans to strike at Manassas thanks to Rose O’Neal Greenhow, a wealthy widow whose society connections and advantageous Washington address near the White House allowed her to ply Union army officers for information that she could relay to the Confederacy. Her information of McDowell’s plan to move on Manassas was delivered to Beauregard the same day McDowell’s troops were marching to meet the enemy.

Marching through Virginia

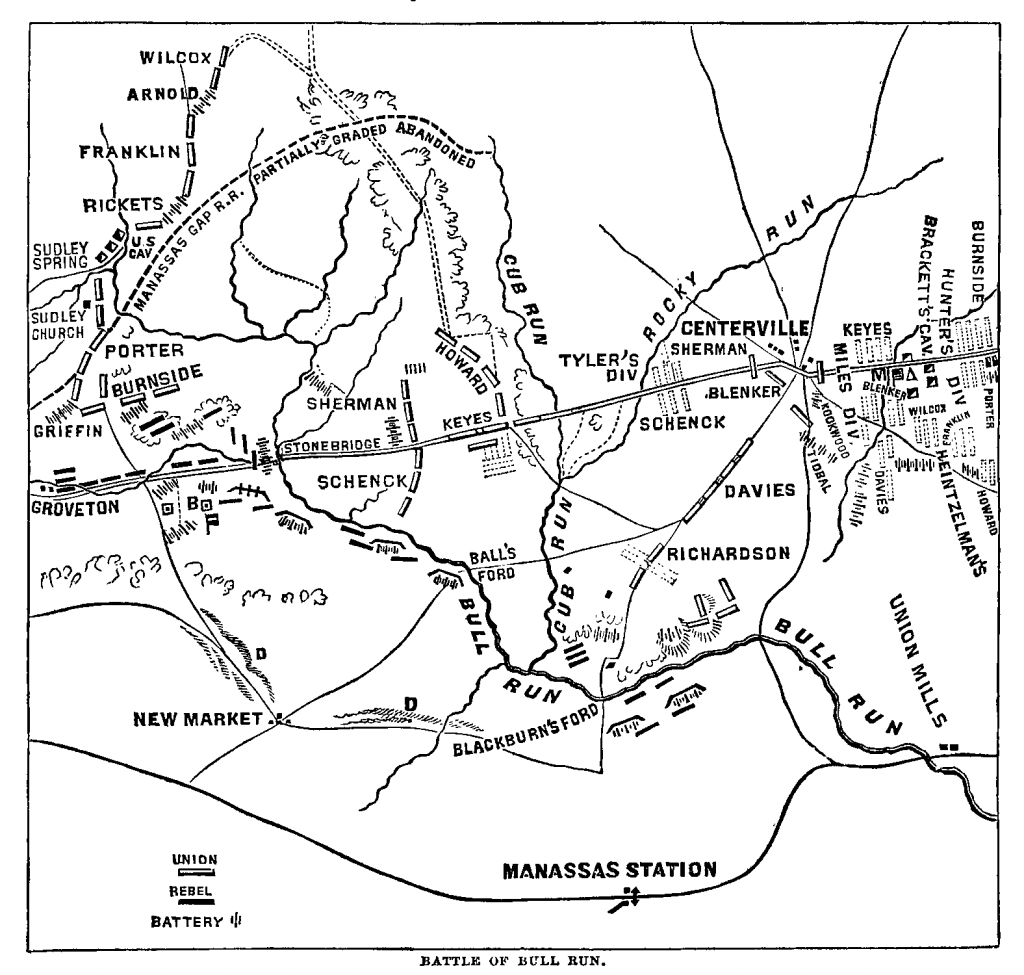

McDowell’s unseasoned troops marched slowly in the hot July sun towards Manassas. Dividing his army, McDowell sent troops under Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler to scout a possible point to ford Bull Run Creek. Attempting to cross at Blackburn Ford, they met Confederate troops under the command of Brig. Gen. Joseph Longstreet. Repulsed by the Confederates and fearing his initial strategy to flank them on the right was now ruined, McDowell sent out scouts to assess the possibilities of flanking the Confederates on the left, including launching the Enterprise, a balloon built and operated by civilian Thaddeus Lowe for aerial reconnaissance. The intelligence gathering also gave McDowell time to wait for resupplies, including fresh water, to arrive for his exhausted men.

This delay allowed Beauregard time to take two critical actions. First, he was able to withdraw and consolidate his forces along the south side of Bull Run Creek, and secondly, he asked Confederate President Jefferson Davis for reinforcements from General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah, who were defending the nearby Shenandoah Valley and its railroad junctions. The Army of the Shenandoah was comprised of 12,000 troops whose brigades were under the command of five officers, including Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson. On July 19th, the day after the skirmish at Blackburn Ford, using the rail lines within their territory, the first of Johnston and Jackson’s troops arrived to reinforce Beauregard at Manassas Junction. Meanwhile, morale among McDowell’s men was low. They had suffered a defeat at Blackburn Ford and thousands of ninety-day enlistments were about to expire. Some terms already had, with regiments turning around to march back to Washington despite McDowell’s pleas for them to stay. Worried he was running out of time, McDowell at last planned to attack on July 21st, with divisions striking at Sudley Springs Ford (on the Confederate’s exposed left flank), with a diversionary force attacking on the Warrenton Pike where it crossed Bull Run Creek at the Stone Bridge.

From the start, McDowell’s plan was not executed as designed. His inexperienced troops and their equally inexperienced commanders delayed moving into place, setting back their offensive strike by several hours. But in the early dawn hours, with troops finally in place, Union Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler began his artillery fire across Bull Run Creek. The battle had officially begun.

“Give Them the Bayonet”

As the morning broke and Confederate troops moved into place, spectators from Washington arrived in numbers so great they clogged the roads into Manassas. Families, reporters, and congressmen crowded on nearby hills with picnic baskets to watch what was surely to be the first and last battle of the war.

McDowell’s master plan—to flank his unsuspecting enemy at Sudley Springs—nearly worked, until the glint of soldiers’ bayonets caught the attention of Confederate Capt. E. Porter Alexander, a signal officer. He signaled to Confederate Col. Nathan Evans to “Look out for your left.” Evans left behind a small force to hold the diversionary attack at the Stone Bridge and turned the bulk of his troops to block the lead Union assault at nearby Matthews Hill alongside troops commanded by Brig. Gen. Barnard Bee and Col. Francis Bartrow. Beauregard, and the main concentration of the Confederate forces, however, were unaware of the feint. Cannon fire ripped across Matthews Hill. Union troops pushed the Confederates back to Henry Hill. The sound of distant cannon fire on his left flank alerted Beauregard to the true movements of the Union forces, who were beginning to overwhelm Evans, Bee, and Bartrow’s men. Before Beauregard could arrive to support his retreating troops, Confederate General Jackson arrived with Colonel J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry and additional artillery. Bee, rallying his men to stand and fight, pointed to the newly arrived Jackson and said, “There is Jackson standing like a stone wall!” giving the general the moniker that would stick with him for eternity. Bee himself would be mortally wounded in the fighting that followed.

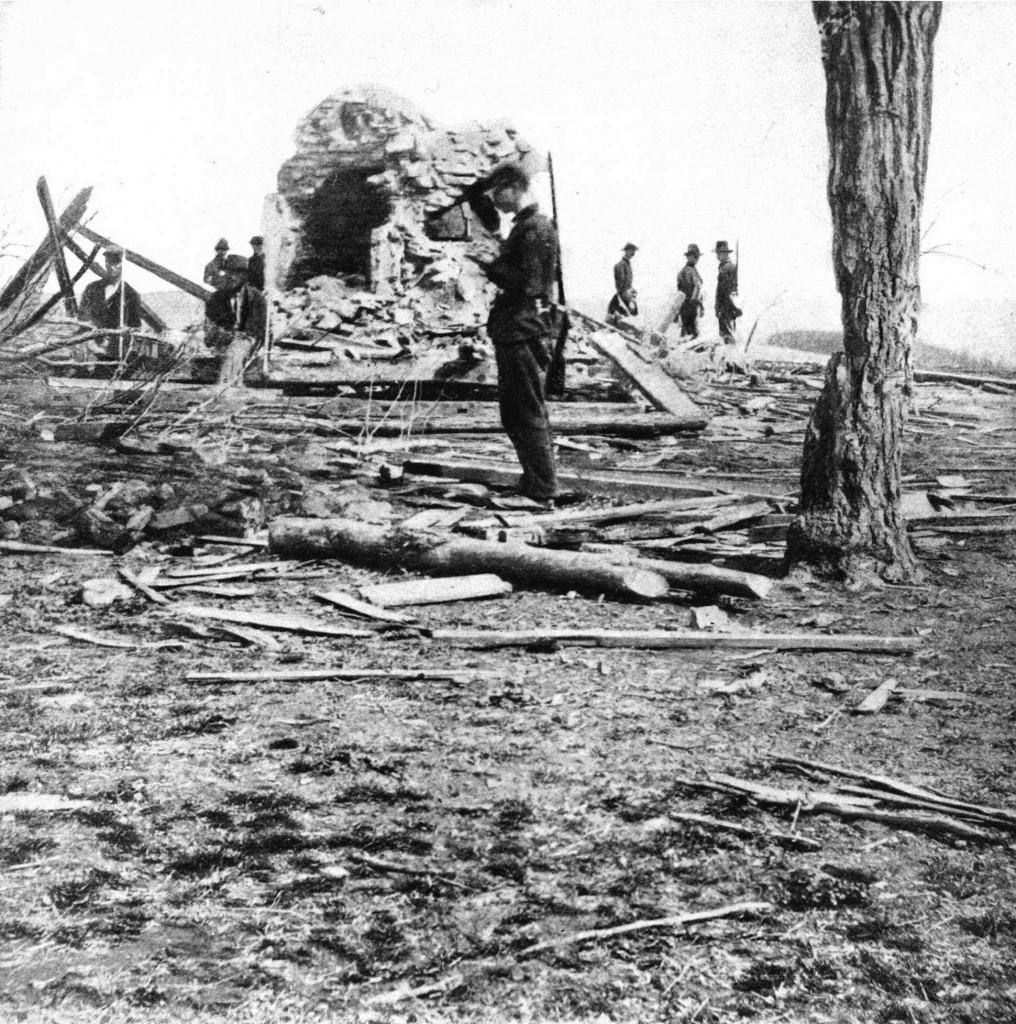

Fighting on Henry Hill was fierce. Beauregard, now aware that the Union forces were on the verge of claiming victory there, redirected his forces. With additional Confederate reinforcements arriving via the Manassas Gap railroad, McDowell’s attack was crumbling, his men exhausted and overwhelmed. The Union army began to retreat, chased by Confederate cannon fire, and the civilians who had come to watch the end of the war suddenly realized they were in the middle of the fighting. Roads already crowded by civilian carriages became impassable with the influx of retreating troops as the Confederates fired, blasting apart carriages and artillery wagons, clogging the Stone Bridge. Blind panic devolved the retreat into a rout. Wounded soldiers grasped at the carriages of civilians in hope of refuge while others cut horses from their harnesses to ride them away. Congressman Alfred Ely of New York, one of the spectators from Washington, was captured in the panicked stampede and taken prisoner by the Confederates. In the midst of the melee, Confederate President Jefferson Davis arrived on horseback just in time to watch the Union army retreat.

Four More Years

Psychologically, the battle had a high toll, confirming for both sides that this Civil War would not be a brief historical footnote, but rather a long, bloody fight. The day after their defeat at Manassas, President Lincoln issued a proclamation for another 500,000 volunteers—with three-year enlistments instead of ninety days. McDowell was relieved of his command on July 25 and was replaced by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan; McClellan would assume command of all the Union armies until he too, like McDowell, was ousted in November 1862 after the Union defeat at the grizzly Battle of Antietam. Three months after Mansassas, Congress established the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War to investigate the state of the Union Army and the reasons for their defeat both at Manassas and in the engagements that followed. Read the full report here, including its findings on Bull Run.

Approximately 2,300 men on both sides were killed, wounded, or listed as missing in action after Manassas. Eighty-five year-old Judith Henry, a bed-ridden widow who was unable to evacuate her home on Henry Hill before the fighting began, was mortally wounded by the artillery fire that assaulted Henry Hill. Sullivan Ballou, a thirty-two year-old politician and lawyer from Smithfield, RI, was serving as a major with the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry. A week before the battle, he wrote a poignant letter to his wife, expressing his fear over the looming fight and his love for her and their children, but also his love for his country. While leading his men in their assault on Matthews Hill, Ballou was struck by cannon fire and died of his wounds one week after the battle.

Despite those initial optimistic prognostications that the war would only last a matter of months, the American Civil War would last for four long years and cost the lives of some 620,000 men, roughly 2% of the country’s population at the time—the highest number of casualties experienced by the United States in any conflict before or since. Thirteen months after the battle, many of the same soldiers would meet again on the same land to fight the Battle of Second Manassas, a battle that would claim many more lives than the first fray to take place.

Where History Comes Alive

We’re issuing our own call for volunteers—volunteers to subscribe to the HeinOnline Blog. As a subscriber, you’ll receive new posts straight to your inbox, ensuring you’ll always be up to date on the latest features, research tips and tricks, and the ways we’re using HeinOnline to learn about history, current events, and more.