This summer, a landmark decision from the Supreme Court marked a historic win for Native American tribes, acknowledging their rights and forever transforming the justice system of the state of Oklahoma.

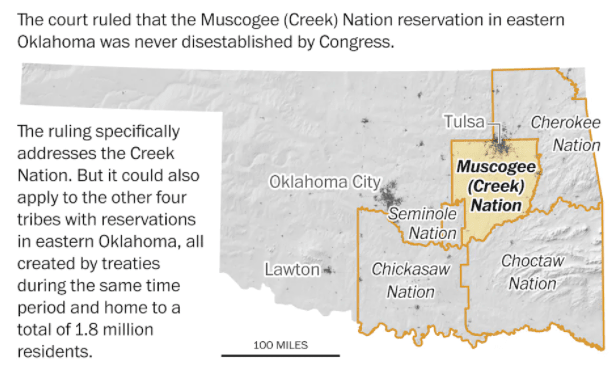

In case you missed it, reports rang out through July and August that half of the state had been ruled Native American land. However, in many cases, the headlines were misleading. Yes, the Supreme Court came to a major decision about criminal jurisdiction in Oklahoma—but no, the Court did not rule specifically on land ownership.

Curious about how it all went down? Explore the landmark decision, its background, and what was actually affected by the ruling with HeinOnline.

A Brief History of Native Americans in Oklahoma

Colonization Becomes “Manifest Destiny”

When European colonizers arrived in North America in the 1600s, the continent was not unpopulated land ripe for the taking. Though estimates vary widely, the native population totaled at least tens of millions—at most, possibly close to a hundred million. Unfamiliar diseases brought by the newcomers contributed to a significant decline in the indigenous population, as did the violence, displacement, and enslavement that would ensue.

In the centuries to come, the formation of the United States would be an experiment in democracy and freedom unlike that of any nation before it. Many U.S. citizens felt that their young country was destined to extend this experiment across the whole of North America. Unfortunately, it soon became apparent that “manifest destiny” could be hampered by an “Indian Problem”—the fact that millions of indigenous people already lived in their own autonomous nations throughout the land, and particularly in the deep South.

Native Relocation and the “Trail of Tears”

Specifically, a group of Indian nations known as the “Five Civilized Tribes”—Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole—had lived for hundreds of years throughout what is now the southern United States. To address this “Indian Problem,” the federal government came up with a plan to relocate these tribes as the United States’ territory expanded. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law, authorizing the government to eliminate Indian title to these lands and to systematically relocate the tribes.

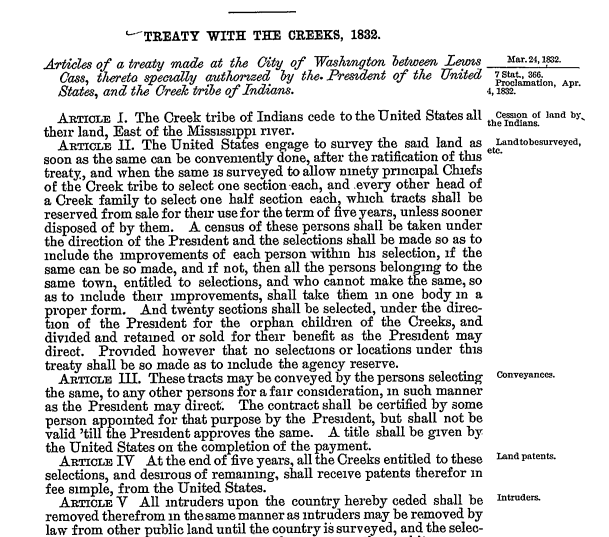

In exchange for their peaceful and voluntary removal, the federal government made the five tribes (and for our purposes, the Creek Nation, specifically) a promise. An “Indian Territory” would be dedicated to those displaced, the United States pledged, encompassing millions of acres west of the Mississippi River. With the promise written into treaty in 1832, the Creek tribe (among others) agreed to be uprooted and relocated westward.

The move would become known as the “Trail of Tears,” a hundreds-of-miles-long trek undertaken by approximately 60,000 Native American peoples. More than 4,000 never reached the land they were promised, dying from exposure, starvation, or disease along the way.

Tens of thousands did arrive in “Indian Territory,” however, and at first, the promise looked as though it would be kept. In 1856, Congress signed another treaty with the Creek tribe that “no portion” of Creek lands “would ever be embraced or included within, or annexed to, any Territory or State.” Ten years later, the United States entered into yet another treaty that formally described some of these lands as the Creek Reservation.

However, the natives in Indian Territory were soon to be disappointed. In 1907, the territory was incorporated into the new state of Oklahoma.

The Broken Promise Resurfaces

Understanding McGirt v. Oklahoma

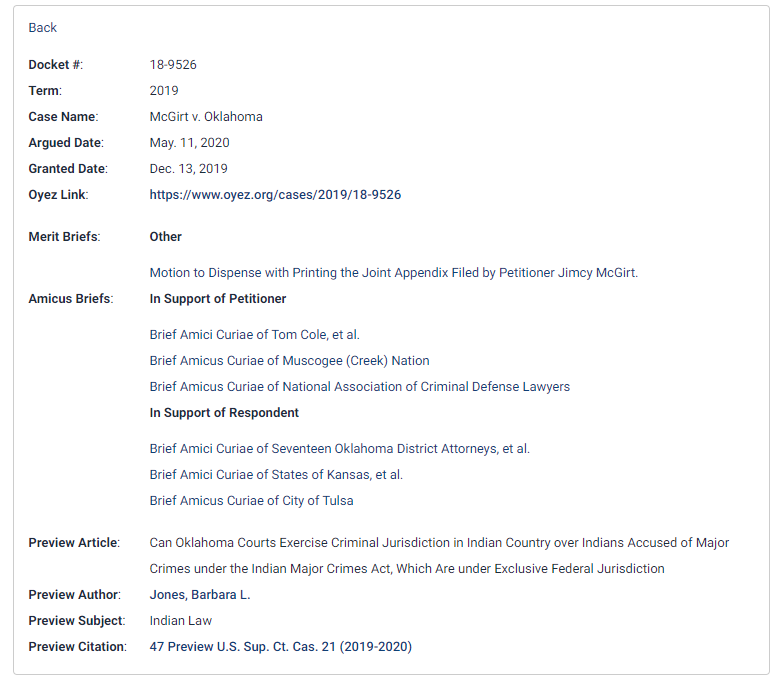

Nearly 90 years later, enter Jimcy McGirt—a Native American man in Oklahoma who was caught for molesting, raping, and sodomizing his wife’s four-year-old granddaughter. In 1997, McGirt was convicted and received a life sentence, but later filed a challenge to the state’s authority to prosecute. He argued that his offenses had occurred in the “Indian Territory” that was previously promised to the Creek Nation and never “disestablished”—meaning that the land was Native American-owned, not state. Further, the Major Crimes Act of 1885 states that certain significant crimes committed on Native American land must rise to the jurisdiction of the federal government. Therefore, McGirt argued, his case should be retried in federal court.

In 2019, the Supreme Court granted McGirt’s petition and arguments were heard on May 11, 2020. Notably, McGirt v. Oklahoma was one of a few cases that used teleconferencing to hear oral arguments for the first time in the Court’s history. Ultimately, some Justices had qualms about ruling that the reservations were never disestablished, arguing that the result would be a ripple effect impacting several areas: existing convicted prisoners in the state of Oklahoma; future convictions in the state; the federal courts that would need to take on an additional thousands of felonies a year; and numerous other civil legal matters that would then fall under tribal purview, rather than the state’s.

On July 9, 2020, the Court held in favor of McGirt in a 5-4 decision. Written by Justice Neil Gorusch and joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan, the majority opinion stated that Congress had failed to disestablish the Indian reservations and those lands should be treated as “Indian country.” Justices John Roberts, Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh, and Clarence Thomas dissented, stating that the decision “creates significant uncertainty for the State’s continuing authority over any area that touches Indian affairs, ranging from zoning and taxation to family and environmental law.”

View a full summary of McGirt v. Oklahoma, expert analysis of the case, linking to Oyez, case briefs, and more in HeinOnline’s Preview of United States Supreme Court Cases.

The Impact of the Decision

Though the media covered the decision as a ruling that gave “half of Oklahoma” back to Native Americans, McGirt v. Oklahoma did not discuss land ownership—just criminal jurisdiction. The Creek lands featured in the case, which include the major city of Tulsa, remain owned almost entirely as private property by non-tribal members.

Regardless, the ruling is still considered a big win for Native American tribes who have long felt overlooked by the Supreme Court. The decision gave the Creek Nation its inherent sovereign power to prosecute minor crimes involving Indians, and Gorusch’s opinion acknowledged that Congress has made and broken many promises to Native Americans over the centuries.

Now, Native American tribal citizens that are convicted under state law for crimes committed on reservation lands may have a case for wrongful conviction. Depending on the crime, their prosecution (and the prosecution of those who commit crimes on those lands in the future), would become either a matter of the tribal courts or the federal courts—but no longer a matter of the state’s.

The Supreme Court today kept the United States’ sacred promise to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of a protected reservation. Today’s decision will allow the Nation to honor our ancestors by maintaining our established sovereignty and territorial boundaries.

Research Native American History and Law

Want to find more Native American treaties? Interested in learning more about the intersection of Native Americans and the law? Find the answers to your questions in HeinOnline’s American Indian Law Collection.

American Indian Law Collection

With more than 2,000 titles unique to this collection and more than 1.3 million total pages dedicated to American Indian Law, this library includes an expansive archive of treaties, federal statutes and regulations, federal case law, tribal codes, constitutions, and jurisprudence. This library also features rare compilations edited by Felix S. Cohen which have never before been accessible online.

See the database in action in our American Indian Law Collection LibGuide.