Does the presidential election cycle have you wondering every four years, “Hey, what exactly is the Electoral College?” With Election Day in the U.S. less than one week away, and millions of Americans having already cast their ballots either by mail or through early voting, HeinOnline has expanded its U.S. Presidential Library to include a new subcollection dedicated to explaining how the electoral college system works, the history of its formation, debates around its efficiency, as well as efforts to reform and even abolish it.

What Is the Electoral College?

Established by Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution, the Electoral College is the formal body which elects the President and Vice President of the United States. The number of electors in a given state is equal to the sum of their Congressional membership (their number of representatives in the House plus their number of Senators, with the District of Columbia having three electors). Each state has its own process for choosing the people who serve as their electors, and most states have adopted legislation enforcing their electors’ pledge to their state’s winner to prevent what is known as faithless electors, or electors casting a vote for a candidate other than the one to whom they were pledged to by the people’s vote on Election Day.

On Election Day, voters are not actually choosing the president; instead, they are voting for the electors who will cast their ballots for that candidate in the Electoral College. 48 states plus Washington D.C. have a “winner-take-all” approach to assigning their electors, meaning the candidate who has the most votes in a state gets all of that state’s electors, while Maine and Nebraska assign their electors using a proportional system. There are currently 538 electors, and to win the presidency a candidate must earn at least 270 electors. If no candidate reaches the magic number of 270, a “contingent election” is held, where the House of Representatives chooses the new president from among the top three candidates, with the Senate choosing the vice president from the remaining two candidates. This has only happened twice: in the election of 1800, as depicted in the popular musical Hamilton, and in 1824, when the House elected John Quincy Adams to the presidency.

While Americans know Election Day is the Tuesday after the first Monday in November, the actual Electoral College vote takes place in mid-December, when electors gather in their respective state’s capital to cast their votes. These results are counted by Congress in a joint meeting held in the first week of January. It is then that if a candidate does not receive 270 votes that the contingent election would be held.

It is possible to lose the nationwide popular vote but win the Electoral College. This has happened four times in American history: in 1876, when Rutherford B. Hayes assumed the presidency after a controversial and disputed electoral college vote; in 1888, when Benjamin Harrison won the electoral vote and defeated incumbent Grover Cleveland; and in recent memory, in the presidential elections of 2000 and 2016. While history has often debated the validity of the Electoral College system and whether to switch the presidential election process to a direct national popular vote, in reality the closest America has ever come to abolishing the Electoral College came in 1969, when the House voted to advance a Constitutional amendment that would have abolished the Electoral College. Endorsed by President Richard Nixon, the proposal was filibustered in the Senate and failed.

Exploring the Subcollection

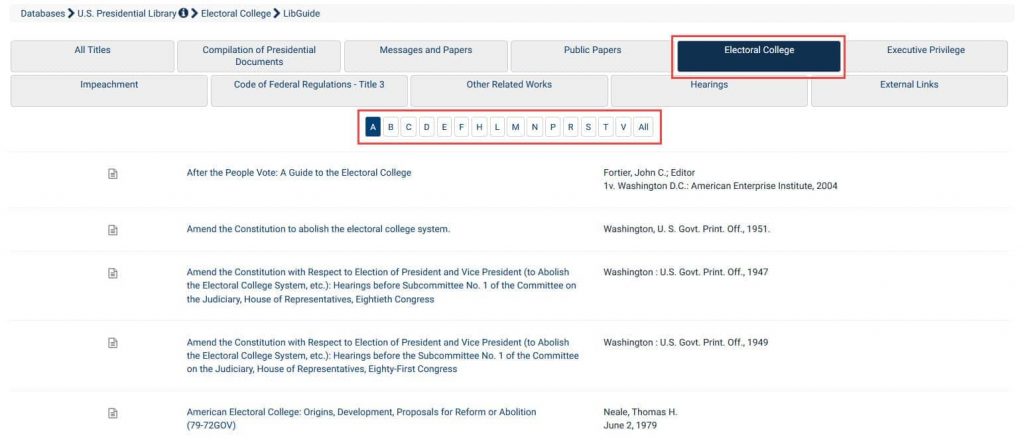

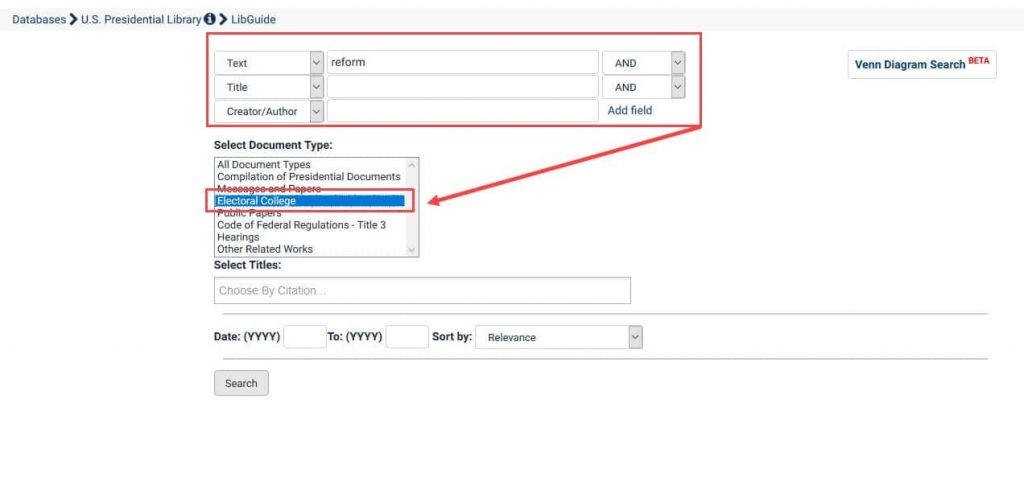

This subcollection brings together hearings, committee prints, CRS and GAO reports, books, treatises and more on the electoral college, explaining it, exploring it, and criticizing it. Navigate using the A-Z anchor or jump into the U.S. Presidential Library’s Advanced Search and use the Select Document Type box to search for content within the Electoral College subcollection.

Or, start your research with these titles that are related to some of the items and historical touchstones mentioned earlier in this blog post:

- Contingent Election of the President and Vice President by Congress: Perspectives and Contemporary Analysis (2020).

- Electoral Count of 1877. Proceedings of the Electoral Commission and of the Two Houses of Congress in Joint Meeting Relative to the Count of Electoral Votes Cast December 6, 1876, for the Presidential Term Commencing March 4, 1877 (1877).

- Electoral College Reform: Hearings before the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, Ninety-First Congress, First Session on H.J. Res. 179, H.J. Res. 181, and Similar Proposals to Amend the Constitution Relating to Electoral College Reform (1969).

- Supreme Court Clarifies Rules for Electoral College: States May Restrict Faithless Electors (2020).

Rounding out this subcollection are documents relating to other election issues, including election security and barriers to voting, including:

- Election Security: Hearing before the Committee on House Administration, House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixteenth Congress, First Session (2020).

- Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election (Vol I and II) (2019).

- Voter Choice 2000: A 50-State Report Card on the Presidential Elections (2000).

- Waiting to Vote: Racial Disparities in Election Day Experiences (2020).

Sign in now to explore this expansion of the U.S. Presidential Library, and don’t forget to cast your vote on November 3rd!