This month, HeinOnline continues its Secrets of the Serial Set series by delving into the question of Puerto Rico—how did the island become a U.S. territory? As U.S. citizens, how do Puerto Ricans participate in American democracy? Should the territory ultimately become an American state?

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative monthly blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Documents from additional HeinOnline databases have been incorporated to supplement research materials for non-U.S. related events discussed.

The U.S. Congressional Serial Set is considered an essential publication for studying American history. Spanning more than two centuries with more than 17,000 bound volumes, the records in this series include House and Senate documents, House and Senate reports, and much more. The Serial Set began publication in 1817 with the 15th Congress, 1st session. U.S. congressional documents prior to 1817 are published as the American State Papers.

The Serial Set is an ongoing project in HeinOnline, with the goal of adding approximately four million pages each year until the archive is completed. View the current status of HeinOnline’s Serial Set project below.

The Exploration Age

The 1400s marked a rise in exploration as European adventurers began to sail westward, discovering a completely New World in the process. These new lands promised exotic foods, untold riches, and abundant resources, leading European nations back home to increasingly adopt policies of expansionism. Monarchies such as Portugal and Spain gradually became grand colonizing empires, with England, France, and the Netherlands soon to follow.

Columbus Lands at Puerto Rico

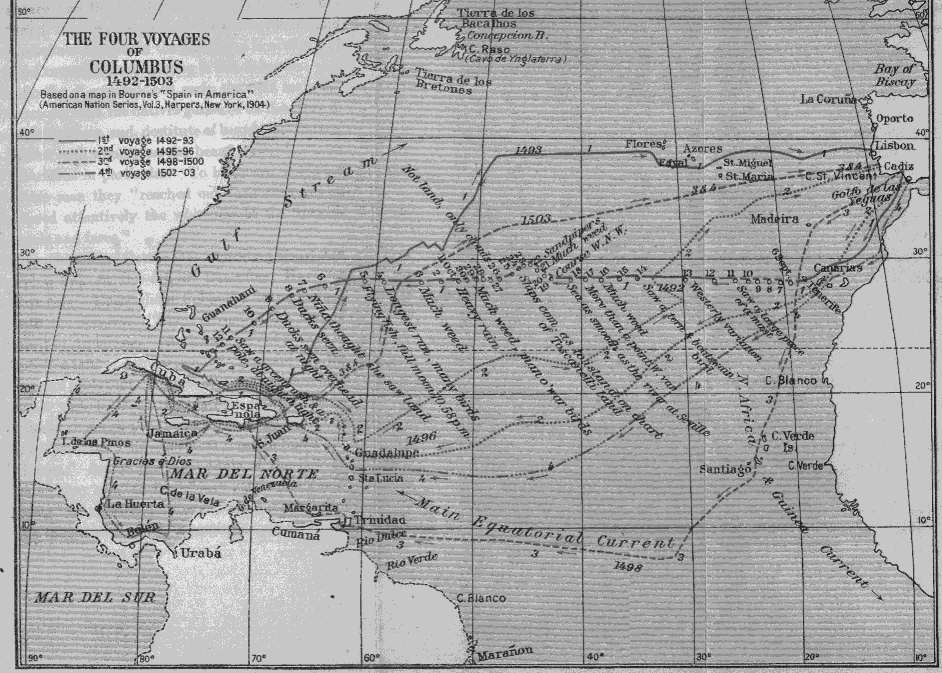

As even the smallest of schoolchildren may know, this expansion began with Christopher Columbus, who sailed the ocean blue in 1492, landing in the region now known as the Bahamas. Lesser known, however, is that Columbus later embarked on a second voyage in 1493, this time stopping at what is now known as the island of Puerto Rico—though he originally named the island “San Juan Bautista,” in honor of Saint John the Baptist. Today, the island remains the only portion of U.S. territory where Christopher Columbus ever set foot.

Upon arrival in “San Juan Bautista,” the Europeans encountered the Taíno people, indigenous inhabitants of the surrounding islands who, according to Columbus, demonstrated surprising civility and generosity. He was thrilled—these traits made them easy to subdue. Later, upon his return to the Taíno people, Columbus began to require regular tribute from these natives. If the Taíno did not provide gold, cotton, or other resources every three months, the Spanish would cut off their hands as punishment.

Understandably, behavior like this did not sit well with the Taíno. Across their native lands (now Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, and of course, Puerto Rico), some began to revolt against the Spanish invaders. In the early 1500s, a member of Columbus’ expedition—Juan Ponce de León—was tasked with squashing this rebellion, and in 1508, this task led him to San Juan Bautista. There, he was able to subdue the Taíno, force them into labor, and, as a result, return to the Spanish king with a significant quantity of gold.

Governor Ponce De León

Ponce de León’s great success led him to receive governorship of the island. He and others founded the first Spanish settlement, Caparra, and distributed the Taíno people among themselves as slaves. Harsh treatment from the Spanish and the introduction of new diseases, however, ultimately took a severe toll on the indigenous population, so slaves were imported from Africa to make up the difference.

A few decades later, 80-90% of the Taíno had perished and the island’s capital settlement was relocated to the bay, then renamed Ciudad de Puerto Rico (“Rich Port City”).

More than 100 years before the English pilgrims of yore landed on Plymouth Rock, Ponce de León moved on from the island of San Juan Bautista to ultimately discover Florida. Thus, the island that we now know as Puerto Rico was really the first entry into the exploration and settlement of the future United States.

The Spanish-American War

Laying the Groundwork

Throughout the late 15th century to the early 1800s, Spain’s successful expansion (and subjugation of indigenous peoples) led the empire to amass a vast overseas territory in both the Caribbean Sea and the “Indies” in the Pacific. The Crown’s power over islands such as Puerto Rico, in particular, allowed it to produce in-demand crops and resources like sugar cane, ginger, tobacco, coffee, gold, and silver.

Realizing the literal and figurative fruits of the Americas, other European powers tried (and failed) to wrest control from Spain of its new lands. By the time England was settling its first colonies in the New World in the 1600s, Spain had become one of the most powerful empires across the globe. Fast forward a century later to find England attempting to suppress its now-revolting colonies and Spain past its peak in colonialism, just in time for a new player to enter the ring—the United States of America.

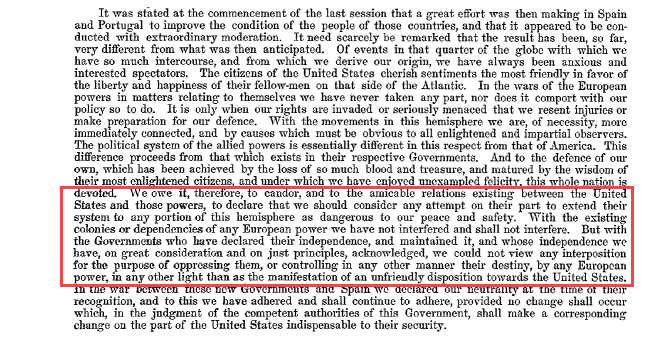

In its youth, the United States dictated the Monroe Doctrine in a State of the Union address delivered to Congress by President James Monroe. The doctrine warned European states to cease colonization or other interference in the Americas, as such activity would be considered hostile against the United States. At a time when many of Spain’s colonies were attempting to achieve independence, Monroe’s policy also forbade European states from retaking control of an independent state in this region.

The U.S. Sets Its Sights on Latin America

A few decades later, the fledgling United States had matured and even experienced its first Civil War. As the nation attempted to reconstruct both the society and the economy, it expanded economic interests in Latin American markets such as the sugar industry in the Spanish colony of Cuba. Recognizing the value potential in creating a shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, the U.S. also explored the possibility of a trans-isthmus canal in Nicaragua or Panama, while at the same time, increasing its naval protection with a new fleet of warships.

Whispers of Cuban revolt in the late 1800s put U.S. interests at risk, so the nation set out to restore stability to the Spanish province. President William McKinley, in an effort to quell the revolutionaries peacefully, attempted negotiations with the Spanish government, but the latter refused to take part. Check out all of the documents and correspondence relating to the affairs in Cuba and Spanish-American negotiations in the Serial Set.

Spain and the Maine

Word of rebel demonstrations taking place in Cuba then led U.S. Consul Fitzhugh Lee to request an American warship that would ensure the safety of U.S. citizens and interests there. In January of 1898, the U.S.S. Maine was launched from Key West, Florida to dock in Havana, Cuba. Three weeks later, on February 15, 1898, an explosion of unknown origins sank the Maine in Havana’s harbor, killing 250 American sailors. All eyes turned toward Spain.

Whether or not Spain was behind the explosion remains unclear, but one thing is certain—it made diplomacy with the United States immensely difficult for Spain. Though President McKinley strongly opposed a Spanish-American war even after the explosion—seeking to preserve the prosperity achieved since the Civil War—he was pressured from many sides, including the American people and Congress. An incendiary speech from Republican Senator Redfield Proctor in March of 1898 only served to strengthen the pro-war cause.

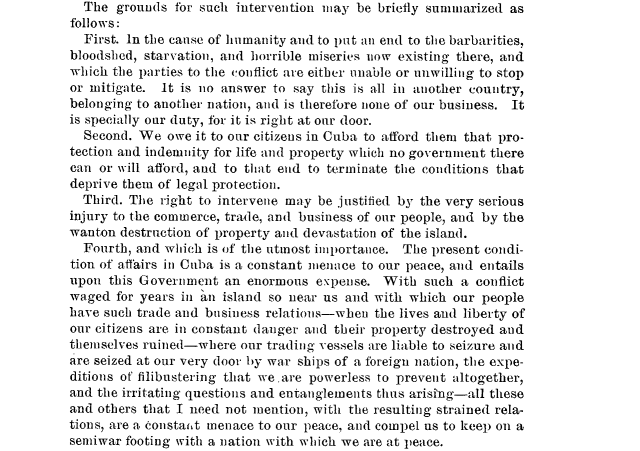

On April 11, McKinley finally acted on the nation’s war cries, asking Congress for the authority to send U.S. troops to the island of Cuba.

Spain cut diplomatic ties with the United States on April 21, and two days later, declared war. For more information about the Spanish-American war and Cuba, in particular, refer to this compilation of documents relating to foreign relations with Spain in 1898.

What About Puerto Rico?

The Spanish-American war had begun. America proceeded with a strategy to seize and retain Spanish colonies in both the Atlantic and the Pacific—namely, Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam. Though small, Puerto Rico was of crucial importance to the United States as a way to guard the Caribbean and the passage to the Isthmus of Panama. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt made this clear when writing to a senator:

“You must get Manila and Hawaii, you must prevent any talk of peace until we get Porto Rico and the Philippines as well as secure the independence of Cuba.”

On May 12, 1898, a squadron of 12 U.S. Navy warships attacked the capital, now called San Juan, and established a blockade in the bay. Spanish ships counterattacked, but were incapable of breaking the blockade. In July, the United States’ offensive began on land, and by August, Americans had swept across Porto Rico and established control of both land and sea. On August 13, McKinley and French Ambassador Jules Cambon (representative for Spain) signed a ceasefire armistice, with Spain conceding its sovereignty over the island. Read further about operations in Puerto Rico during the war with this summary.

With additional defeats in Cuba and the Philippines, Spain surrendered, and on the afternoon of August 12, signed a Protocol of Peace with the United States. After two months of negotiations, the Treaty of Paris was signed in December of 1898 and ratified by the Senate in 1899. Following its ratification, the United States acquired the Spanish colonies of the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico, while Cuba became an American protectorate. Find additional papers relating to the treaty here.

Interested in learning more about Spain’s rule over Puerto Rico? Check out this history of the island.

Want to learn more about the history of Spain? Access this overview within HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated.

America Takes Over

After centuries of existing under Spanish rule, the island we now know as Puerto Rico found itself under military control of the United States of America. This transfer of power had its benefits—freedoms of speech, religion, assembly, and press were guaranteed, a central public health system was established, and transportation systems were updated and expanded. The United States further changed the name of the island to Porto Rico, changed the island’s currency from the peso to the U.S. dollar, and outlawed public displays of the Puerto Rican flag, only allowing that of the United States.

The Foraker Act

In 1900, after determining the legal status of its newly acquired territories, the U.S. military government on the island was replaced with a civilian government with the passage of the Foraker Act. This new government included a U.S.-appointed governor and executive council (also all appointed, and less than half of whom could be Puerto Rican), an elected House of Representatives, and a judicial system led by a Supreme Court. The act further required that all bills passed by the new legislative branch be sent to the United States Congress for review.

The United States further embarked on an “Americanization” campaign of Puerto Rico. Aspects of the campaign were beneficial, such as the modernization of the sugar industry, which boosted the island’s economy. However, some attempts at “Americanization” also contributed to a general uneasiness on the island—for example, the demotion of Spanish to an elective secondary language in Puerto Rican schools (leading to significant dropout).

During this time, multiple political groups appeared on the island, each of which typically aligned their interests with one future path for “Porto Rico”—the acceptance of the island as a state, the establishment of the island as a commonwealth, or the declaration of Puerto Rican independence. This 1910 report on the conditions of Porto Rico demonstrates the political unrest simmering on the island at the time.

In response, Congress passed the Olmsted Amendment, which created an executive department for the Puerto Rican government. Though its members were still designated by the U.S. President, the act also allowed Puerto Rican natives to hold a majority in the executive council for the first time. However, the amendment wasn’t enough, and Congress found itself hounded with Puerto Rican requests for more opportunities for self-government.

Jones Act of 1917

In 1914, the European continent was launched into World War I. After the sinking of the S. S. Sussex in 1916, the United States entered the war, as well.

That same year, Congress worked to grant U.S. citizenship to anyone born in Puerto Rico on or after April 11, 1899. Some natives in the territory had pushed for this outcome, and citizenship allowed eligible males to be entered into the U.S. military draft—so it killed two birds with one stone, so to speak.

U.S. citizenship for Puerto Ricans was officially granted with the passage of the Jones-Shafroth Act. The legislation superseded the Foraker Act, created an elected Senate, and established a bill of rights for Puerto Rican residents. Unfortunately, not all residents were appeased. Many found citizenship without statehood lacking, or interpreted the act as a way to ignore or even circumvent any calls for Puerto Rican independence. Regardless, a few months later, tens of thousands of Puerto Rican men were sent to the war front.

The Great Statehood Debate

Rising Anti-American Sentiments

Many of those unhappy with the Jones Act joined a newly established political group—the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. Known for flying the Puerto Rican flag (a felony since 1898), the party pushed back against attempts at Americanization and other U.S. activity that would interfere with Puerto Rico’s eventual independence. In the 1930s, the party’s president, Pedro Albizu Campos, was arrested for conspiracy to overthrow the American government, but the party lived on, particularly with Puerto Rican students.

In 1935, students planned to hold an assembly at the University of Puerto Rico-Río Piedras campus. In case of possible violence, Governor Blanton Winship (appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt) sent armed police officers to the school. After a confrontation with the Secretary of the Nationalist Party, police fired their weapons. The resulting five deaths are known as the “Río Piedras massacre.”

The next year, two Nationalists killed an American colonel in San Juan, presumably in retaliation for the massacre. They were taken into custody and later killed by police.

In 1937, the Nationalist Party organized what was claimed to be a peaceful march. Under the orders of Governor Winship, police reportedly opened fire at the parade, resulting in another massacre of 18 participants, the deaths of two policemen, and more than 100 injured persons. After this “Ponce massacre,” an attempt was made on the life of Governor Winship at a military parade the following year—the first assassination attempt on a Puerto Rican governor in its history. A total of 36 people were wounded in the attempt, but the governor was unharmed.

Post-World War II

The volatility seen in the years leading up to World War II died down during the Great Depression and World War II. In 1946, Jesús T. Piñero was appointed governor of the island—the first Puerto Rican governor appointed in the island’s history. By this time, the center-left Popular Democratic Party (in favor of Puerto Rico as a U.S. Commonwealth) controlled the Puerto Rican Senate. In 1948, the government approved a historic bill known as the Ley de la Mordaza (Gag Law) that would drastically change Puerto Rican society for the next nine years.

The new law was passed with the purpose of suppressing Puerto Rican movements for independence. Under the law, it became a crime to speak about independence, hold meetings in favor of independence, sing patriotic tunes, or own or display a Puerto Rican flag. The punishment for these actions included ten years imprisonment and/or a fine up to $10,000 dollars (an amount equivalent today to more than $100,000).

Meanwhile, the U.S. relinquished some control over the island by passing legislation that would allow Puerto Ricans to elect their governor. Further, in 1950, President Truman signed the Puerto Rico Federal Relations Act, allowing the territory to draft its own constitution and establish its own government (under that of the United States, of course). Under the act, the new constitution was subject to the approval of the U.S. President and Congress. That same year, Puerto Rican nationalists in New York City attempted to assassinate Truman, but failed.

In 1952, Puerto Rican voters put forth their first constitution under the name Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico (“Free Associated State of Puerto Rico”). The United States gave its approval, but adjusted the English translation of the territory name to “Commonwealth of Puerto Rico” (as the island would not be considered a full state). The same year saw the Puerto Rican flag legally displayed in public for the first time since 1898.

Since the 1950s, the status of Puerto Rico has been a reoccurring question. In 1967, a referendum was held on the matter, with more than 60% of voters preferring to continue Commonwealth status. 0.6% of the vote preferred statehood. Two others were held in 1993 and in 1998—in both cases, the majority of voters preferred to uphold the status quo.

Still today, Puerto Rico’s political status under U.S. rule remains somewhat ambiguous. Officially, the island is an unincorporated organized U.S. territory that is self-governing, yet it remains under U.S. congressional supervision. According to the U.S. Constitution, Puerto Rico could only become a state with the approval of Congress; however, until as recently as two years ago, Congress has shown little interest in changing its status—in 2019, the Puerto Rico Admissions Act was introduced in the House to enable Puerto Rico’s incorporation as a state. The bill received a total of 42 Democrat and 18 Republican cosponsors, but did not reach a vote on the House floor.

Help Us Complete the Project

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us, please contact Shannon Hein at 716-882-2600 or shein@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give special thanks to the following libraries for their generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

- Wayne State University

- University of Utah

- UC Hastings

- University of Montana

- Law Library of Louisiana

- George Washington University

- University of Delaware

We will continue to need help from the library community to complete this project. Download this Excel file to see what we’re still missing.