When any slightly incendiary word is uttered in Congress, the media is quick to report it. Today, live coverage of congressional proceedings and social media-driven insta-news has made us all well aware of any tiffs, squabbles, or fallings-out in Washington. As a result, we’re also well aware that strong disagreement in the Capitol is, as to be expected, very common.

There was a time in American history, though, when disagreements became so heated that they turned physical, ranging from a singular blow to a vicious beating, and even to murder. In the pre-Civil War era, Congress saw at least 70 violent incidents between its members. Let’s just say that if C-SPAN had existed in the early 1800s, it probably would’ve been a lot more exciting.

Join HeinOnline in investigating congressional violence in the antebellum period using the following databases:

Overview of the Antebellum Era

Antebellum America typically refers to the United States after the American Revolution (1783) and before the American Civil War (1861). Characterized by rapid technological growth, cultural growth in the form of art and literature, and westward exploration and expansion, the period saw significant economic, political, and social changes that contributed to great polarization of the country.

Economic Polarization

In the late 1700s, Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin (a machine that quickly separates cotton fibers from their seeds), along with the introduction of power looms and sewing machine, raised the demand of cotton. By 1815, cotton had become the primary cash crop of the South. Cotton plantations were thus incredibly profitable, but also heavily dependent on large amounts of labor.

Slaves, which had existed in the United States since the country’s colonial days, were a source of labor that could never resign, never demand higher wages, and which would provide continued labor for generations. Larger plantations meant more cotton, more slaves, and therefore more wealth. Later on, as Southern land decreased in quality over time, plantation owners found that their wealth increasingly existed not in cotton and other crops, but in the slaves themselves.

While Whitney was developing the cotton gin, Englishman Samuel Slater emigrated to New England with a plan in mind for developing water-powered machinery that could spin cotton. In 1793, he opened America’s first water-powered textile mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, ushering in the American Industrial Revolution. Further advances soon occurred in other industries as well, including paper, glass, paint, and equipment manufacturing.

The North had been no stranger to slavery until this point, but the gradual move toward industry over agriculture prevented the institution from becoming a fact of life deeply embedded in society. In fact, the rise of factories brought with it the concept of wage labor, which became more prevalent than family labor, apprenticeship, indentured servitude, and, of course, slavery.

Other Polarizing Factors

Multiple other factors intertwined to further polarize these two already-different regions. For one, it was widely held across the country that the young United States had a certain moral superiority in both people and institutions, and was destined to spread its values throughout the rest of North America. Continued Western expansion and annexation reinforced this concept of “Manifest Destiny,” and the values and practices that were to be instilled in each new state became a point of contention.

Meanwhile, an influx of immigration occurred in the early 1800s and mid-century during the Gold Rush. Most initially flocked to the boom towns of the Northeast in search of economic opportunity, cementing further the economic, social, and cultural differences between the North and the South.

Then, a religious revival now known as the Second Awakening—fueled in part by a spread of Romantic art and literature—led to the development of various social reform movements focused on temperance (abstinence from alcohol), education and literacy, and the abolition of slavery in its entirety. Women played a crucial role in the development of these movements, and thus saw increased influence outside of the family home—giving rise, in turn, to the development of the women’s rights and suffrage movement.

Finally, amidst all of this action, the impact of the Industrial Revolution on the printing industry expanded the scale and reach of the newspaper business. By 1860, thousands of different newspapers existed in the United States, increasing awareness and disagreement about these issues (particularly slavery) across the nation.

Antebellum Violence in Congress

These rapid advancements, escalating social movements, and deep-seated regional differences fostered an unstable political environment, evidenced by an increase in violence in Congress as the years drew closer to the American Civil War. In fact, by the 1840s and 50s, congressmen were known to carry pistols and knives onto the House and Senate floors as they debated various issues—for example, whether slavery should extend into newly acquired territories.

At least 70 violent incidents between members of Congress have been identified. Let’s dive into a few of the more notable ones with HeinOnline.

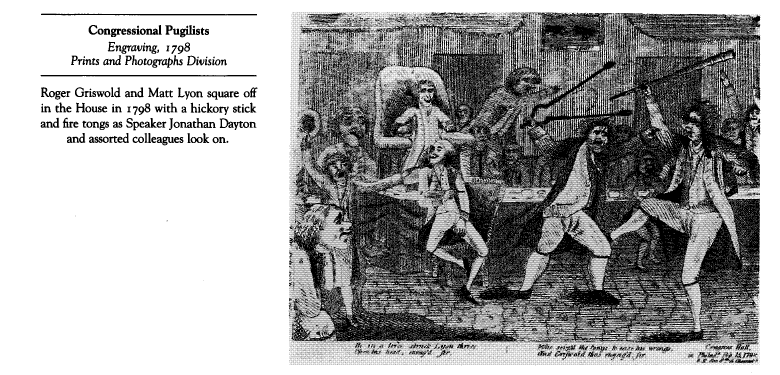

1798: An Attack in the House

On January 30, 1798, the U.S. House of Representatives held a hearing on the impeachment of William Blount, a Senator from the newly-admitted Tennessee. Federalist Congressman Roger Griswold attempted to rile Democratic-Republican Representative Matthew Lyon up about the matter, but Lyon deliberately ignored him.

Losing his temper, Griswold called Lyon a “scoundrel” (profane language for the time). As the tiff escalated, Lyon spat in Griswold’s face. A few weeks later, Griswold entered the House floor and attacked Lyon with a wooden walking stick, while Lyon attempted to defend himself with tongs from the nearby fireplace. The brawl was broken up after a few minutes, but as a result, Lyon was the first Congressman to have charges filed against him with the House’s ethics committee—though the House ultimately rejected censure of either party.

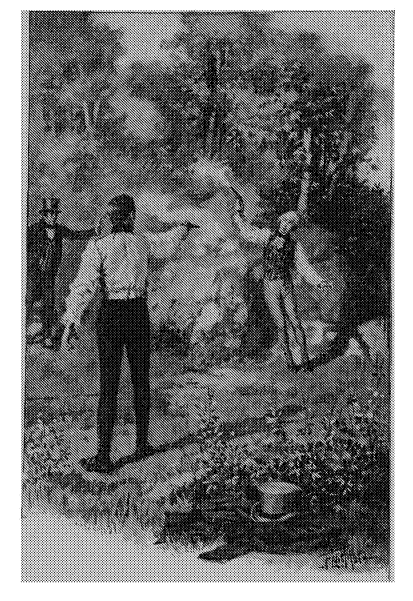

1838: A Congressional Duel

By the late 1830s, political partisanship had only increased, and matters weren’t helped by the economic Panic of 1837. The Whig and Democrat parties fought bitterly over how to respond to the financial crisis, and newspapers—now growing in number and popularity due to the Industrial Revolution—covered the situation with their own political biases.

Democrats, like Congressman Jonathan Cilley, considered coverage by Whig-affiliated papers to be unfair. Cilley brought up the matter on the House Floor, specifically citing the New York Courier and Enquirer and suggesting corruption. The editor of the paper was insulted, and convinced a Whig congressman, William J. Graves, to deliver a letter to Cilley challenging him to a duel.

When Cilley refused to even accept the letter to read it, Graves’ own honor was insulted. He subsequently challenged Cilley to his own duel. After two rounds of missed shots, Cilley was killed near-instantly by Graves’ third bullet to an artery in the thigh. Graves and two other congressmen in attendance were recommended for censure. The House refused, but pushed through legislation to prohibit the challenging, accepting, or fighting of duels in the District of Columbia.

Today, the Cilley-Graves duel remains the only case where one congressman has ever killed another.

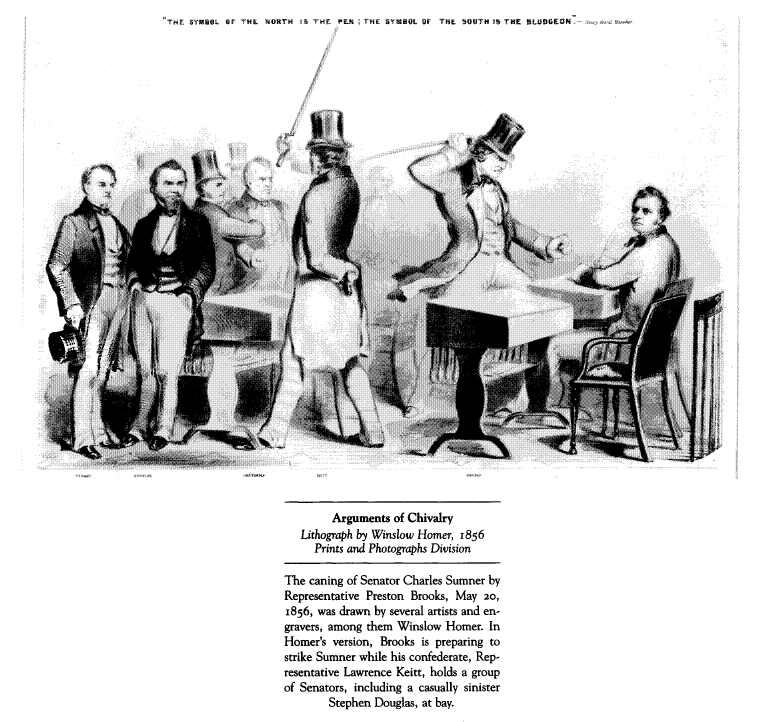

1856: The Caning of Charles Sumner

In 1854, the political and ideological debate over whether slavery should be allowed in the new state of Kansas resulted in the Kansas-Nebraska Act—a law which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise (which had outlawed slavery north of latitude 36°30′) and left the slavery decision up to the vote of Kansas settlers themselves. The act contributed to tension and division, not just in the territory itself, but nationally as well. Two years later, the tension erupted in raids, assaults, and murders on the part of both pro and anti-slavery activists. This period of violence has become known today as “Bleeding Kansas.”

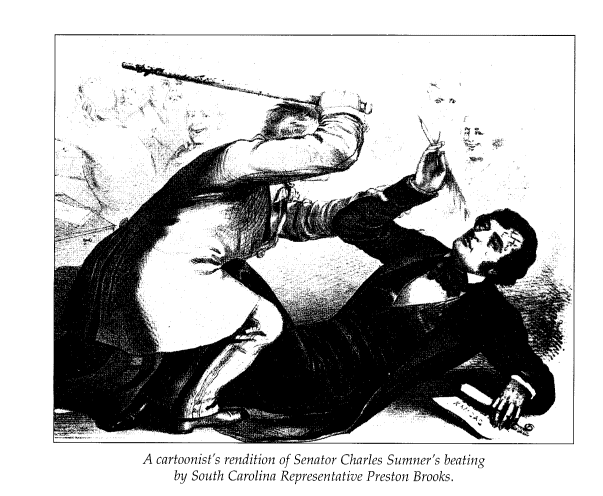

During “Bleeding Kansas,” abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner criticized the Kansas-Nebraska Act in a lengthy speech that attacked the authors of the legislation and called for Kansas’ admission as a free state. Preston Brooks, a relative of one of the act’s authors (and himself a pro-slavery Democrat), was incensed. Deciding that Sumner was not even honorable enough for a duel, Brooks and fellow representative Laurence Keitt devised a way to hurt and humiliate him.

On May 22, 1856, Brooks, Keitt, and Congressman Henry Edmundson approached Sumner, who sat at his desk in an almost-empty Senate chamber. When Sumner stood up, Brooks used a thick wooden cane to beat him in the head, knocking him down and causing him to lose sight almost immediately. Brooks continued to cane Sumner across his head and shoulders as the senator lay pinned under his desk, and even when Sumner managed to stumble away and up the aisle. Even when his cane snapped and after Sumner went unconscious, Brooks continued his assault. Meanwhile, Keitt and Edmundson used their own canes and pistols to block bystanders from assisting the senator.

Ultimately, Brooks was restrained and left the chamber while Sumner was left lying on the chamber floor, drenched in blood. Newspapers from all corners of the country reported the violence that had occurred. Northern publications made a martyr of Charles Sumner, and Southern papers praised Brooks’ attack.

Sumner suffered for the rest of his life with what we could identify today as traumatic brain injury, along with symptoms of PTSD. Brooks was arrested, convicted, and fined, but did not receive prison time, nor was he expelled from the House. In fact, he was re-elected to a new term later that year, though he died before it began. Keitt, for his part, was censured by the House, but was also overwhelmingly re-elected within a month of the incident. Read a transcript of the ensuing congressional investigation here.

1858: Brawl on the House Floor

In the 1850 congressional elections, Galusha Grow ran as a Democrat. Following the signing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act mentioned earlier, Grow switched to the newly-formed Republican Party and continued to be a member for the remainder of his career.

Two years after he had helped beat Charles Sumner to the brink of death, Democrat Laurence Keitt found himself in a House debate in which he was offended by Congressman Grow. Grow, amidst delivery of an anti-slavery speech, had stepped over to the Democratic side of the House chamber, where Keitt felt he no longer belonged.

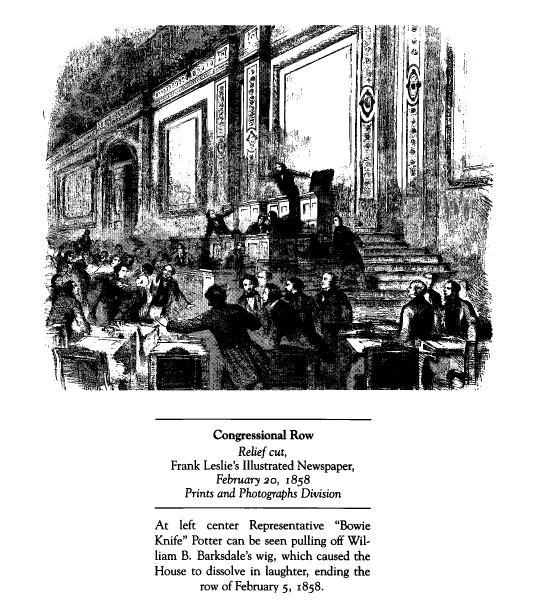

Keitt ordered Grow to sit down, calling him a “black Republican puppy,” to which Grow responded: “No negro-driver shall crack his whip over me.” Infuriated, Keitt lunged for Grow’s throat, initiating a massive brawl on the House floor that involved nearly fifty Congressmen. The brawl only ended when one representative missed a punch, instead knocking the wig of his intended victim askew. When the man unintentionally replaced the hairpiece backwards, Democrats and Republicans alike reportedly burst into laughter.

Grow later became Speaker of the House on the same day that Keitt’s home state of South Carolina, after declaring its secession from the Union, attacked the U.S. Army’s Fort Sumter, beginning the Civil War. Keitt later died while serving as a Confederate soldier at the Battle of Cold Harbor.

Americans were shocked by the attack on the Capitol building this past January. Such violence surrounding our democratic institutions seemed unheard of and unprecedented. Reflecting briefly on our country’s history, however … it may no longer seem that far-fetched.

We can argue that the politicians involved in these antebellum incidents were simply attempting to serve the people, values, and institutions of their own particular regions. But looking back on just how indicative these incidents were of the country’s division, one can’t help but wonder whether America’s Civil War might have been prevented, at least in part, by more rationality and more dignity in its statemen.

Like This Post? Read More on the HeinOnline Blog

Do you enjoy learning about history, politics, or other disciplines? We do too.

Several members of the HeinOnline team contribute to the HeinOnline blog to make database research not only easy, but enticing. Peruse the blog to discover content relating to law, international relations, criminal justice, human rights, women’s studies, and many more. Subscribe to the blog to receive this quality content right to your inbox.