How many times have you suspected that your neighbor was casting spells in their backyard? Or your best friend was talking to spirits? Or your own mother was possessed by the devil? In 1692 Salem, Massachusetts, accusing someone of witchcraft quickly became a common occurrence. Mass hysteria and paranoia combined with a rudimentary legal system meant that anyone could be convicted of being a witch—and sentenced to death because of it.

Explore this Bewitching Subject with HeinOnline

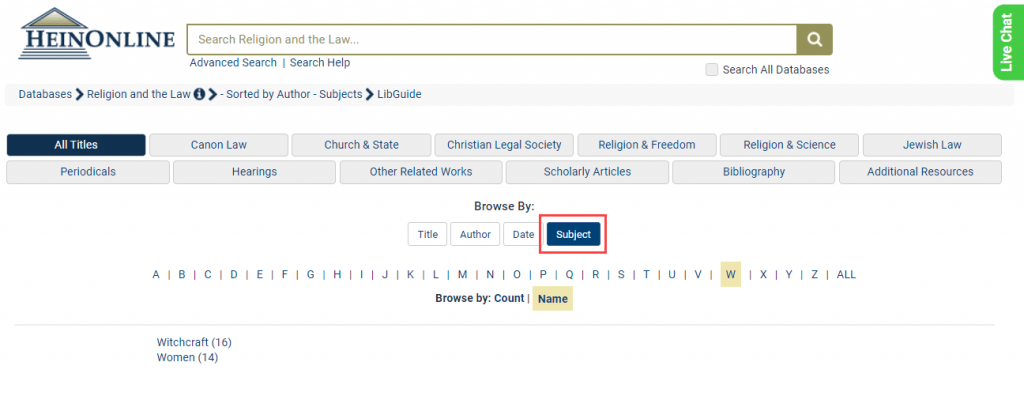

Witchcraft has been a subject of interest, derision, fear, and speculation since before our nation was built—and lucky for you, HeinOnline is brewing with resources where you can uncover more about the Salem Witch Trials and its impacts on today’s legal system. For example, check out our World Trials Library, where you’ll find selections such as Records of Salem Witchcraft, Copied from the Original Documents,[1]W. Elliot Woodward. Records of Salem Witchcraft, Copied from the Original Documents (1864). This book is located within HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. What Happened in Salem: Documents Pertaining to the 17th-Century Witchcraft Trials,[2]David Levin, Editor. What Happened in Salem: Documents Pertaining to the 17th-Century Witchcraft Trials (1952). This book is located within HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. and The Salem Witch Trials: A Chapter of New England History.[3]William Nelson Gemmill. Salem Witch Trials: A Chapter of New England History (1924). This book is located within HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. Or, visit the Religion and the Law database, where you can find “Witchcraft” under the Subject search.

The Witching Hour: Salem, MA, 1692

It wasn’t just the colonies that found themselves obsessed with witchcraft and the desire to burn witches at the stake[4]Len Niehoff, Proof at the Salem Witch Trials, 47 LITIGATION 21 (2020). This article is located within HeinOnline’s ABA Law Library Collection Periodicals database. (although, in fact, the Salem witches were hanged rather than burned). Witch hunts were commonplace in Europe, especially in Germany, France, and Scotland. England was also under witch hysteria: The Witchcraft Act of 1542 was the first act decrying witchcraft as a felony, and the Witchcraft Act of 1604 declared the penalty of death to anyone invoking or communing with spirits.

The anti-witch sentiment eventually made its way to Britain’s colonies in America—for example, the Maryland Assembly adopted the Witchcraft Act of 1604 just a few decades later in 1635. In addition, the God-fearing, Puritanical culture of the colonies created immense fear surrounding evil spirits and the devil. Lack of scientific knowledge meant that anything out of the ordinary could be easily attributed to supernatural causes. And with political upheaval in England, many of the colonies didn’t have functioning government bodies. Salem, for example, did not have a foundation for a stable government. When William Phips, the newly appointed governor of Massachusetts Bay Province, returned from England in May of 1692, he found himself amidst witch-hunting chaos. A wealthy man with no law background, Phips created the Court of Oyer and Terminer (meaning “to hear and determine”) to deal with all the witchcraft accusations. Three of the men he appointed as judges were close friends with clergyman Cotton Mather, one of the main supporters of the witch hunts.

It all began when teenage girls in the colony began to mysteriously fall ill and act strangely. They accused Tituba, an enslaved South American woman, of summoning spirits, subsequently resulting in their illness. The accusations spread like wildfire, and soon the whole town was accusing different people—mainly, but not always, women—of witchcraft. And by the end of the year, 180 people would be accused and 20 people killed.

A Cursed Court

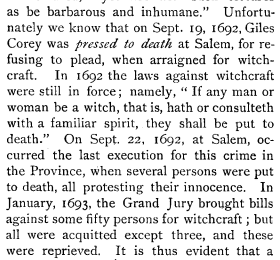

Massachusetts law was derived from the Holy Bible’s Book of Exodus: “If any man or woman be a witch that is, hath, or consulteth with a familiar spirit, they shall be put to death. Exod, 22. 188; Deut. 13.6, 10; Deut. 17.”[5]Austin A. Martin, Gleanings from Early Massachusetts Laws, 2 GREEN BAG 295 (1890).This article is located within HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

These court cases would be considered absurd compared to today’s legal standards. In 1692, there was no “innocent until proven guilty.” The accused were often tortured or forced into pleading guilty; some were told that their lives would be spared if they admitted to witchcraft or turned in other “witches.” Evidence was based on hearsay, meaning that witness statements were written before the trial even began. These statements were likely transcribed by Thomas Putnam, a man who, having acted as complainant in many cases and testifying in 17, couldn’t necessarily be considered unbiased.[6]Len Niehoff, Proof at the Salem Witch Trials, 47 LITIGATION 21 (2020). This article is located within HeinOnline’s ABA Law Library Collection Periodicals database. Definitive rules banning hearsay from court wouldn’t come about until the Federal Rules of Evidence was published in the 1700s.

In addition, many of the testimonies against the so-called “witches” were simply based on opinions of character. Someone could accuse someone else of being a witch simply because they didn’t like them. Unpleasant encounters, personal vendettas, and rumors were all fodder for accusations. Today, slander is illegal, but in 1692 it was frequently a large factor in determining a death sentence.

At the time, there were many widely held beliefs about witches. [7]Len Niehoff, Proof at the Salem Witch Trials, 47 LITIGATION 21 (2020). This article is located within HeinOnline’s ABA Law Library Collection Periodicals database. For example, it was generally believed that witches were in a compact with the devil, who appeared on earth as a darkly dressed man. Therefore, anyone seen conversing with a man wearing dark clothes could be accused of being a witch. Witches also were expected to have a mark on their bodies—a cut, scar, blemish, or birth mark could all be interpreted as being a mark left from feeding a familiar. Witches could also change shape, fly, or appear in spectral form, which meant that accusers could claim that they encountered an accused witch in a dream or vision, and it would count as legitimate evidence. Owning a doll could be used as evidence—witches were thought to use dolls, referred to as “poppets,” to cast their spells. But, because of the irrational nature of these beliefs, even the absence of this evidence could be used against someone. As the Reverend George Burroughs was being executed for witchcraft, he perfectly recited the Lord’s Prayer—an act thought to be impossible for a witch. Cotton Mathers simply explained that the devil was helping the Reverend out, thus justifying the execution.

Confession (or refusal to confess), testimony of two (often biased) witnesses, and spectral evidence: This was the trifecta that brought innocent people to prison or the gallows.

Located in HeinOnline’s ABA Law Library Collection Periodicals database.

The Bitter End

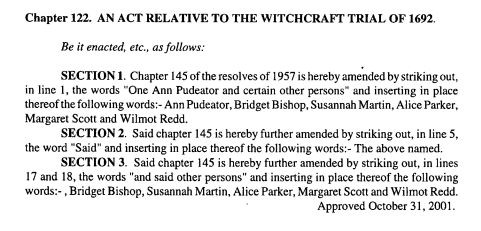

The Salem Witch Trials ended in 1693, when a new Superior Court of Judicature banned the use of spectral evidence, a key component in the conviction of witches. By 1711, Massachusetts had exonerated all of the accused and offered monetary compensation to surviving family members. In 1957, the State of Massachusetts formally apologized, stating, “The General Court of Massachusetts declares its belief that such proceedings, even if lawful under the Province Charter and the law of Massachusetts as it then was, were and are shocking, and the result of a wave of popular hysterical fear of the Devil in the community…”[8]Resolve of Sept. 16, 1957, ch. 145, 1957 Mass. Gen. Ct. 1048. This statement from the Massachusetts General Court is located within HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. But it wasn’t until the end of 2001, more than 300 years later, that the Massachusetts state legislature officially exonerated the final names of the accused witches.[9]Act of Oct. 31, 2001, ch. 122, 2001 Mass. Acts & Resolves 300. This act is located within HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library.

Modern “Witch Hunts”

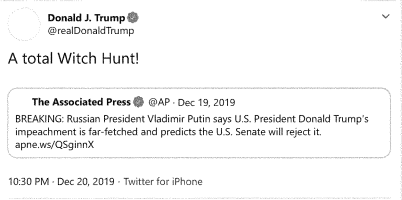

The legacy of the Salem Witch Trials continues to haunt us today. Arthur Miller’s famous play “The Crucible,” published and first performed in 1953, describes the events in Salem, inspired by the eerily similar mass hysteria that at the time was manifesting in the Red Scare, when innocent people were accused and prosecuted for communist beliefs and activities. In 1960, Hon. James V. Bennett,[10]Narcotics Legislation: Hearing before the Subcomm. to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency, 91st Cong. 1038 (1969). This statement from a congressional hearing is located within HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. former Director of Federal Bureau of Prisons, claimed that the harsh treatment of those accused of drug use would someday be compared to the Salem witch trials. And, most recently, former president Donald Trump frequently compared his impeachment process to a witch hunt, writing to Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, “More due process was afforded to those accused in the Salem Witch Trials.”[11]Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Letter to the Speaker of the House of Representatives on the Articles of Impeachment Against the President, Daily Comp. Pres. Docs. 1 (2019). This letter is located within HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential … Continue reading

Today, Salem doesn’t hide its infamous legacy, with museums, tourist attractions, and the Salem Witch Trials Memorial all dedicated to the witch hunt of three centuries ago. The town is, fittingly, especially popular during October, when tales of witches and hauntings and spells and curses come alive for Halloween.

Let HeinOnline Haunt Your Inbox

Subscribe to the HeinOnline blog so you never miss the new tips and tricks, content updates, uncovered history, and all other things related to the vast materials located within our databases, where the ghosts of history live on!

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | W. Elliot Woodward. Records of Salem Witchcraft, Copied from the Original Documents (1864). This book is located within HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | David Levin, Editor. What Happened in Salem: Documents Pertaining to the 17th-Century Witchcraft Trials (1952). This book is located within HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |

| ↑3 | William Nelson Gemmill. Salem Witch Trials: A Chapter of New England History (1924). This book is located within HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |

| ↑4, ↑6, ↑7 | Len Niehoff, Proof at the Salem Witch Trials, 47 LITIGATION 21 (2020). This article is located within HeinOnline’s ABA Law Library Collection Periodicals database. |

| ↑5 | Austin A. Martin, Gleanings from Early Massachusetts Laws, 2 GREEN BAG 295 (1890).This article is located within HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑8 | Resolve of Sept. 16, 1957, ch. 145, 1957 Mass. Gen. Ct. 1048. This statement from the Massachusetts General Court is located within HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. |

| ↑9 | Act of Oct. 31, 2001, ch. 122, 2001 Mass. Acts & Resolves 300. This act is located within HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. |

| ↑10 | Narcotics Legislation: Hearing before the Subcomm. to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency, 91st Cong. 1038 (1969). This statement from a congressional hearing is located within HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑11 | Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Letter to the Speaker of the House of Representatives on the Articles of Impeachment Against the President, Daily Comp. Pres. Docs. 1 (2019). This letter is located within HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |