For this post in honor of Women’s History Month, let’s turn the clock back to America in 1916. World War I had torn Europe apart for the last three years, and the United States teetered on the edge of falling into the conflict. Half the country’s population was under 25 and half of all families lived on farms. Henry Ford’s Model T was an intriguing curiosity, but automobiles were still a rare sight on the roads. In 1916, Congress passed the Adamson Act,[1]39 Stat. 721 (1916). This act is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. which set an eight-hour workday for interstate railroad workers—the first federal law to regulate working hours at private companies. Women did not have the right to vote at the federal level. But this lack of a voice had not prevented Montana from electing Jeannette Rankin to the House of Representatives—the first woman elected to federal office.

In the House of Representatives, 1917-1919

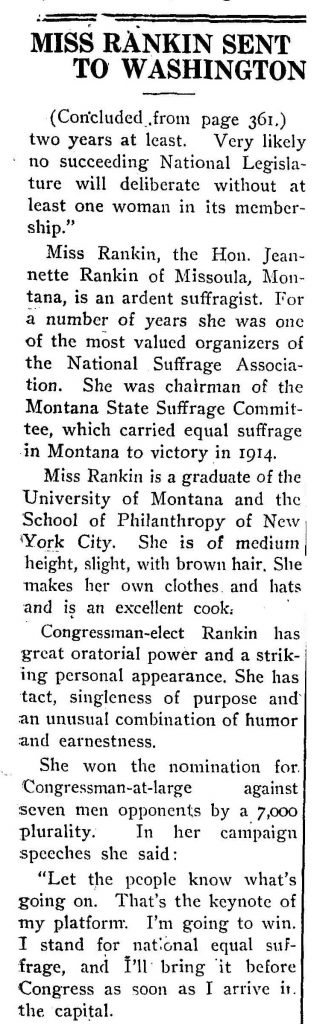

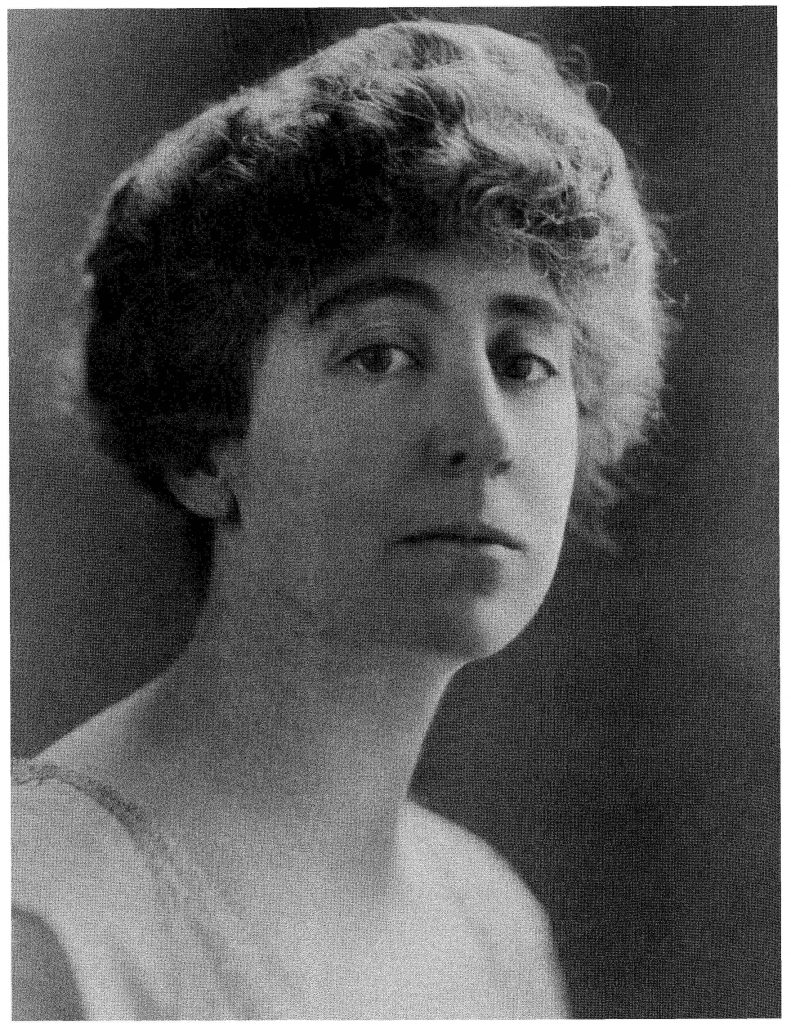

Rankin was the eldest of seven children born to a Montana rancher and a schoolteacher. She earned degrees from the University of Montana and the School of Philanthropy of New York City (now part of Columbia University) before working as a social worker in the state of Washington, but was called to the cause of suffrage reform in 1910. Rankin became a lobbyist for the National American Woman Suffrage Association and returned to her native Montana in 1910 to bring the vote to its female citizens, addressing the Montana legislature[2]47 Woman’s J. & Suffrage News 369 (1919). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database. in 1911 on the subject of its recently introduced suffrage amendment (it later failed). Finally, after touring the state for three years speaking on suffrage in town halls and in schoolhouses,[3]Judith K. Cole, A Wide Field for Usefulness: Women’s Civil Status and the Evolution of Women’s Suffrage on the Montana Frontier, 1864-1914, 34 AM. J. LEGAL Hist. 262 (1990). This article is found in … Continue reading Montana’s women gained the right to vote in 1914. Two years later, Rankin was elected to the House of Representatives. “I am deeply conscious of the responsibility,” Rankin said in her victory speech. “It is wonderful to have the opportunity to be the first woman to sit in Congress with 434 men.”[4]47 Woman’s J. & Suffrage News 369 (1919). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database.

The World War

Rankin was sworn into office during the opening of an extra session of Congress on April 2, 1917.[5]48 Woman’s J. & Suffrage News 86 (1917). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database. That evening, President Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress, asking, “[w]ith a profound sense of the solemn and even tragical character of the step…and of the grave responsibilities which it involves,” for a declaration of war[6]Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Official Statements of War Aims and Peace Proposals, December 1916 to November 1918 (1921). This speech is found in HeinOnline’s History of International Law database. between the United States and Germany. After addressing Congress, Wilson immediately returned to the White House, put his head down, and wept.[7]Glenn R. Capp. Famous Speeches in American History (1963). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics.

Considering that Wilson’s speech had been interrupted by frequent applause,[8]Glenn R. Capp. Famous Speeches in American History (1963). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. which the President found ghoulish, the outcome of House debate on the war resolution seemed all but certain. Rankin, an ardent pacifist, did not participate in House debate.[9]I’m No Lady, I’m a Member of Congress: Women Pioneers on Capitol Hill, 1914-1934, 1 Women in Congress, 1917-2006 (Matthew A. Wasniewski, ed.) 17 (2006). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. In the early morning hours of April 6, the House voted on the resolution. “I want to stand by my country,” Rankin said as she rose to cast her vote. “But I cannot vote for war.”[10]I’m No Lady, I’m a Member of Congress: Women Pioneers on Capitol Hill, 1914-1934, 1 Women in Congress, 1917-2006 (Matthew A. Wasniewski, ed.) 17 (2006). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database.

While 49 other Representatives and six Senators also voted against a declaration of war, Rankin was pilloried for her opposition. The New York Times called her vote “almost final proof of feminine incapacity for straight reasoning.” Back in Montana, the Helena Independent called Rankin “a dagger in the hands of the German propagandists, a dupe of the Kaiser, a member of the Hun army in the United States.”[11]I’m No Lady, I’m a Member of Congress: Women Pioneers on Capitol Hill, 1914-1934, 1 Women in Congress, 1917-2006 (Matthew A. Wasniewski, ed.) 17 (2006). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. It was frequently reported[12]S. Doc. 99-32, 99th Cong., 2d Sess. (1985). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. that Rankin wept, fainted, or was otherwise hysterical after she cast her vote, a version of history rebuked[13]48 Woman’s J. & Suffrage News 86 (1917). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database. by female spectators in the House gallery. The suffrage movement at large worried that outrage over Rankin’s vote would taint its cause, while Carrie Chapman Catt[14]Mary Gray Peck, Carrie Chapman Catt, a Biography (1944). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database. declared that no matter which way Rankin had voted she would have been criticized: “If she voted for war, she would offend pacifists; if she voted against it, she would offend the militarists.”[15]48 Woman’s J. & Suffrage News 86 (1917). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database.

The Battle for Women’s Suffrage

The United States had officially entered World War I. But Rankin turned her legislative efforts towards the battle that had long dominated her working life: securing the vote for women. She helped create a Committee on Woman Suffrage[16]Elizabeth Cady Stanton; et al., History of Woman Suffrage (1922). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database. in the House, and on January 10, 1919, she opened House floor debate[17]56 Cong. Rec. 744 (1918). This is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. on H. J. Res. 200,[18]H. Rep. 234, 65th Cong., 2d Sess. (1918). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. an amendment to the Constitution extending the right of suffrage to women. “The boys at the front know something of the democracy for which they are fighting,”[19]56 Cong. Rec. 744 (1918). This is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. she said at the end of her speech.

These are the fiber and sinew of war—the mother, the farmer, the miner, the industrial worker, the soldier. These are the people who are giving their all for the cause of democracy…. How shall we answer their challenge, gentlemen; how shall we explain to them the meaning of democracy if the same Congress that voted for war to make the world safe for democracy refuses to give this small measure of democracy to the women of our country.”

The resolution to give women the vote passed in the House but was defeated in the Senate.

Public Life, 1919-1940 and Return to Congress

Jeannette Rankin’s congressional term ended before H.J. Res. 200 was resurrected to become the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. Facing a tough re-election thanks to changes in Montana’s House districts, she instead ran for Senate, narrowly losing in 1919. With her time in Congress at an end, Rankin returned to social work and to promoting peace and pacifism,[20]S. Doc. 99-32, 99th Cong., 2d Sess. (1985). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. working for the National Council for the Prevention of War, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and the National Consumers’ League, where she focused on ending child labor.

Having spent most of the 1930s in Georgia, Rankin returned to Montana in 1940 and was again elected to serve the state in the House of Representatives. Her return to Congress coincided with the United States once again on the edge of being pulled into a world war. After Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japan on December 7, 1941, Jeannette Rankin once again was sitting in a Joint Session of Congress listening to the President ask for a declaration of war.[21]Franklin D. Roosevelt. Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt (1941). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. Immediately following Roosevelt’s speech, Congress debated the war resolution, in which Rankin and her pacifist views were repeatedly drowned out by her colleagues. When it was time to vote, Jeannette Rankin was the only member of Congress to vote “no,” declaring “As a woman, I can’t go to war, and I refuse to send anyone else.”[22]S. Doc. 99-32, 99th Cong., 2d Sess. (1985). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

The backlash to Rankin’s vote was immediate and fierce. She was booed by her colleagues and needed a police escort back to her office. She had voted for her beliefs, and it ended her Congressional career. Rankin did not seek re-election in 1942 and left the Hill as the only Representative to vote against the United States entering both World Wars.[23]United States. Capitol: A Pictorial History of the Capitol and of the Congress (1983). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database.

Anti-War Movement and Legacy

In the decades after leaving Congress, Jeannette Rankin stayed mostly out of public life. She spent considerable time in India, inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s nonviolence resistance against British rule, but the Vietnam War brought her back into the public sphere. Fifty years after her first election to Congress, Jeannette Rankin was back in Washington, D.C. in January 1968. She led 5,000 women protestors, known as the Jeannette Rankin Brigade, as they marched on Capitol Hill[24]116 Cong. Rec. 19391 (1970). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. to protest the Vietnam War and deliver a peace petition[25]I’m No Lady, I’m a Member of Congress: Women Pioneers on Capitol Hill, 1914-1934, 1 Women in Congress, 1917-2006 (Matthew A. Wasniewski, ed.) 17 (2006). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. to the House Speaker. She was 87 years old.

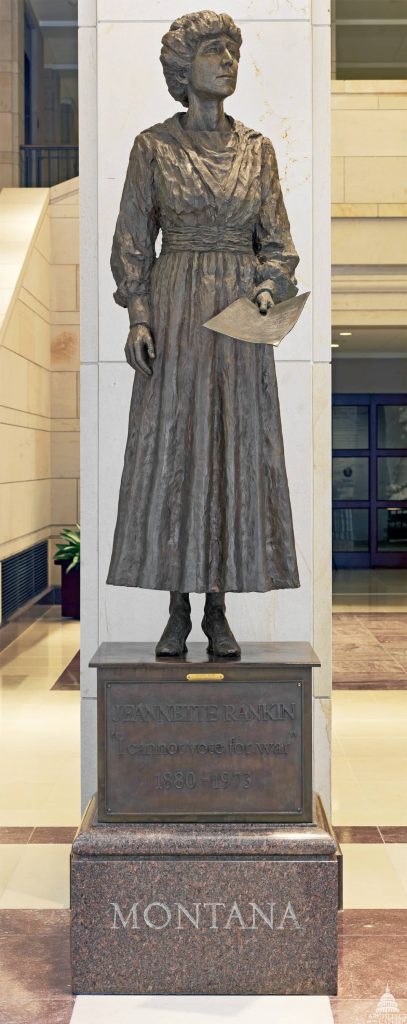

Rankin was considering running for Congress for a third time on an anti-war platform when she died on May 18, 1973, at 92 years old. In 1985, a statue of Rankin[26]S. Doc. 99-32, 99th Cong., 2d Sess. (1985). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. was unveiled in the Capitol’s Statuary Hall, bearing the inscription “I cannot vote for war.” As of 2022, 396 women have succeeded Jeannette Rankin in being elected or appointed to Congress, but Rankin remains the only woman from Montana to serve in Congress.

HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database offers a tremendous collection of resources to help you learn about more amazing women from history, with a dedicated Famous Women subcollection filled with hundreds of biographies. Be sure to subscribe to the HeinOnline Blog to stay up-to-date on how HeinOnline bloggers are using this collection and others to illuminate the past and inform on the present.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | 39 Stat. 721 (1916). This act is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑4 | 47 Woman’s J. & Suffrage News 369 (1919). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database. |

| ↑3 | Judith K. Cole, A Wide Field for Usefulness: Women’s Civil Status and the Evolution of Women’s Suffrage on the Montana Frontier, 1864-1914, 34 AM. J. LEGAL Hist. 262 (1990). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑5 | 48 Woman’s J. & Suffrage News 86 (1917). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database. |

| ↑6 | Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Official Statements of War Aims and Peace Proposals, December 1916 to November 1918 (1921). This speech is found in HeinOnline’s History of International Law database. |

| ↑7 | Glenn R. Capp. Famous Speeches in American History (1963). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑8 | Glenn R. Capp. Famous Speeches in American History (1963). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑9, ↑10, ↑11, ↑25 | I’m No Lady, I’m a Member of Congress: Women Pioneers on Capitol Hill, 1914-1934, 1 Women in Congress, 1917-2006 (Matthew A. Wasniewski, ed.) 17 (2006). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑12, ↑20, ↑22, ↑26 | S. Doc. 99-32, 99th Cong., 2d Sess. (1985). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑13, ↑15 | 48 Woman’s J. & Suffrage News 86 (1917). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database. |

| ↑14 | Mary Gray Peck, Carrie Chapman Catt, a Biography (1944). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database. |

| ↑16 | Elizabeth Cady Stanton; et al., History of Woman Suffrage (1922). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy) database. |

| ↑17, ↑19 | 56 Cong. Rec. 744 (1918). This is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑18 | H. Rep. 234, 65th Cong., 2d Sess. (1918). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑21 | Franklin D. Roosevelt. Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt (1941). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑23 | United States. Capitol: A Pictorial History of the Capitol and of the Congress (1983). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑24 | 116 Cong. Rec. 19391 (1970). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |