The Disney fan community has been abuzz the last few months, over the opening of Epcot’s brand-new rollercoaster, Guardians of the Galaxy: Cosmic Rewind, the debut of the eagerly anticipated Disney+ show Obi-Wan Kenobi, and a bombshell development out of the Florida legislature: the repeal of the Reedy Creek Improvement District. Devotees of Walt Disney World have long been familiar with Reedy Creek, but its recent headline-making repeal was likely the first time many laypeople had even heard of the district. While researchers often turn to HeinOnline to research the past, we can also use it to learn more about these current events in Florida. So put on your Minnie Mouse ears and serve yourself a Dole Whip, and get ready for a Walt Disney World-themed post from HeinOnline.

It’s a Small World After All

After opening Disneyland in Anaheim, California, in 1955, Walt Disney looked eastward for his next amusement park project, eventually settling on the swampland of Orlando, Florida. Using a variety of dummy corporations, including Reedy Creek Ranch,[1]Chad D. Emerson, Merging Public and Private Governance: How Disney’s Reedy Creek Improvement District Re-Imagined the Traditional Division of Local Regulatory Powers, 36 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 177 (2009). This article is found in … Continue reading Walt Disney Productions began buying up over 27,000 acres of land throughout the early 1960s, prompting speculation from locals over who was behind the great land grab. In 1965, Walt Disney publicly confirmed he had purchased the land in Florida for the site of what the press dubbed the “east coast Disneyland.”

As anyone who has vacationed in Walt Disney World knows, the theme park is massive, with approximately half of the original 27,000 acres purchased still undeveloped today. To effectively manage the infrastructure required for such a large park, including the proposed Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow,[2]Todd William Gretton, Responsible Corporate Environmental Policy: Available in Fantasyland; Coming Soon to Main Street U.S.A. – A Glimpse at a Corporate Owned and Operated Special Purpose District and Its Impact on the Environment in Central … Continue reading originally conceived as a real utopian planned city, rather than a destination to day drink around the world, Disney lobbied the governor’s office for special tax status. On May 12, 1967, Florida Governor Claude Kirk signed into law legislation creating the municipalities of Bay Lake and Reedy Creek, which would later be rechristened to Lake Buena Vista, the name it bears today. These two new cities fell within the boundaries of the newly created Reedy Creek Improvement District (RCID). RCID functions as its own government, administering the municipal services found in any city: fire protection, water infrastructure, pest control, road paving, building regulations, and so on.

View a map of the current Reedy Creek Improvement District boundaries here.

Special districts like RCID are not unique to Walt Disney World, but they are not always as exciting as existing to support a Magic Kingdom. Special districts allow citizens to effectively solve municipal problems; they allow local governments to levy taxes against the citizens within it to address some special need,[3]Todd William Gretton, Responsible Corporate Environmental Policy: Available in Fantasyland; Coming Soon to Main Street U.S.A. – A Glimpse at a Corporate Owned and Operated Special Purpose District and Its Impact on the Environment in Central … Continue reading be it fire protection or drainage, that is not otherwise being met. The first special districts in Florida were created in 1822,[4]Chad D. Emerson, Merging Public and Private Governance: How Disney’s Reedy Creek Improvement District Re-Imagined the Traditional Division of Local Regulatory Powers, 36 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 177 (2009). This article is found in … Continue reading long before Florida became a state, to build transportation routes across its swampy outposts.

Taxing Main Street, U.S.A.

Because Walt Disney World was originally meant to include a futuristic, functioning community in the form of Epcot, that would, in the words of Walt Disney, “never be completed, but will always be introducing and testing and demonstrating new materials and new systems,”[5]Todd William Gretton, Responsible Corporate Environmental Policy: Available in Fantasyland; Coming Soon to Main Street U.S.A. – A Glimpse at a Corporate Owned and Operated Special Purpose District and Its Impact on the Environment in Central … Continue reading the Disney Company was keen to be able to administer Epcot on its own terms. It also wanted broad control over the rest of the planned parks, even down to how the outside world looked to visitors from within the parks.

Anyone who has visited the Magic Kingdom or Animal Kingdom might be familiar with the “Disney bubble,” the sense that once on Disney property, they are within a separate world. This is a deliberate design choice. Cast members move goods and themselves through underground walkways. Anyone who has taken a “backstage” tour at Walt Disney World knows that photography in these restricted areas is forbidden, lest any light is shone on the banal nuts and bolts that make the pixie dust in the parks sparkle. The show buildings containing the actual ride apparatus of famous attractions such as the Haunted Mansion are carefully hidden behind landscaping and façade buildings, and remain hidden from view even from the summit of Big Thunder Mountain. Mundane and non-magical necessities are painted in “go away green,” a special color created by Disney that is designed to trick the eye into passing over the offensive, out-of-place object. Disney’s obsessive attention to sightlines extends to power lines and billboards; visitors will never see a utility pole within the park, or drive past advertisements for McDonald’s on I-4 within Reedy Creek. Even highway signs within Reedy Creek are stylized and painted a distinctive color unique in all of Florida. This is a deliberate design choice designed to fully immerse the visitor within the experience of the park. A high level of control over every aspect of the park experience is paramount to Disney, and the Reedy Creek Improvement District allows Disney to execute this.

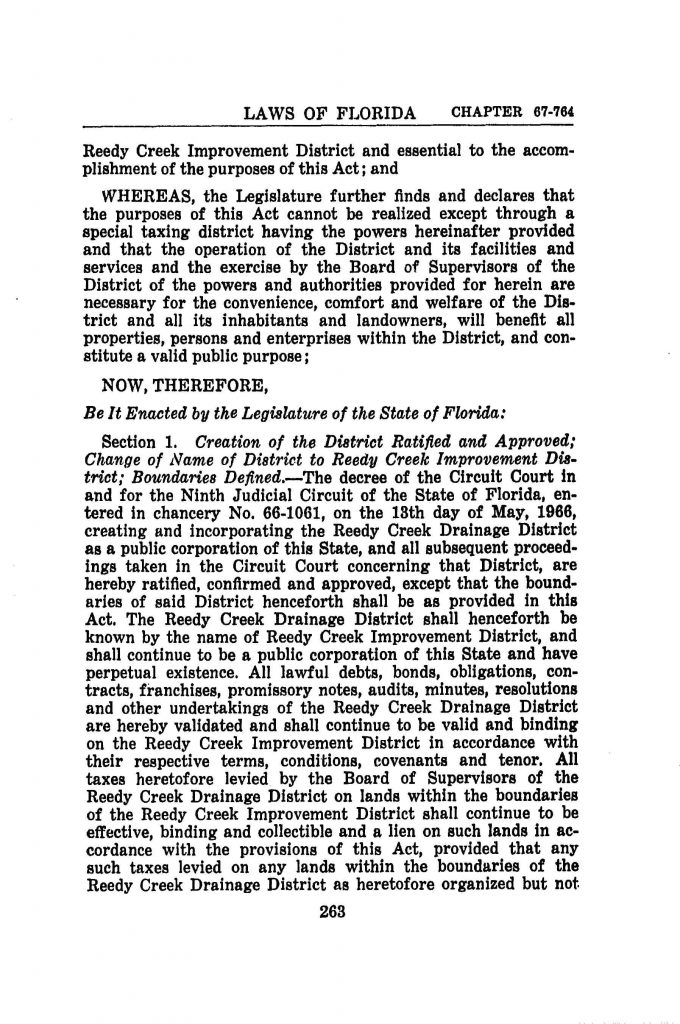

The RCID was originally conceived as a drainage district, created on May 13, 1966, to allow the Disney Company to begin preparing the land for construction. Almost a year to the day later, the Reedy Creek Drainage District was expanded into an improvement district, broadening its authority. The RCID is governed by a five-member Board of Supervisors.[6]Chad D. Emerson, Merging Public and Private Governance: How Disney’s Reedy Creek Improvement District Re-Imagined the Traditional Division of Local Regulatory Powers, 36 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 177 (2009). This article is found in … Continue reading Board members must own land within the District and a majority of members must be residents of Osceola, Orange, or a neighboring county. Board members are elected by District landowners, with eligible voters determined by the amount of acreage they own within the District; with Disney being the primary landowner within RCID, they in effect control the Board of Supervisors. This allows Disney to expeditiously approve new construction projects, repair roadways, and execute whatever is needed to maintain the parks to the standards set by Disney. Projects within the District are paid for by taxes unique to the District that are levied against its landowners (again, the majority being the Disney Company), and this property tax rate is three times higher than the maximum for surrounding counties and cities, in addition to special maintenance and utility taxes that are also levied.

Disney v. World

Reedy Creek’s repeal comes after a protracted fight between the Disney Company and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis over HB 1557, known in the media as the “Don’t Say Gay” bill. HB 1557 sets prohibitions on classroom instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity for Florida public school students from kindergarten to grade 3. As the largest private employer in Florida, Disney CEO Bob Chapek faced intense pressure on social media and from within the company to speak out against the bill, with the company releasing a statement against the bill after it was signed into law.

Disney’s public opposition to the bill provoked the ire of Governor DeSantis, who threatened to dissolve RCID and other special districts created before November 1968. Those threats became a reality on April 22, 2022, when Governor DeSantis signed into law legislation that dissolves RCID effective June 1, 2023. If Reedy Creek is actually dissolved, Orange and Osceola counties will need to absorb the District’s debt—somewhere around $1 billion—and would need to begin providing the municipal services and improvements previously provided by Reedy Creek.

This is not the first threat to its existence RCID has faced. In 1968, the Florida Supreme Court upheld the legitimacy of RCID’s immense power, in State v. Reedy Creek Improvement District.[7]216 So.2d 202. This case is found in Fastcase. The case concerned bonds issued by RCID to pay for drainage and reclamation projects; the State challenged the bonds’ validation, arguing that the bonds constituted “pledging public credit for private use,”[8]Kent Wetherell, Florida Law because of and According to Mickey: The Top 5 Florida Cases and Statutes Involving Walt Disney World, 4 Fla. Coastal L.J. 1 (2002). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. since Disney was the largest landowner in the District and the primary beneficiary of the project. The Florida Supreme Court ultimately rejected this argument, finding the project served a valid public purpose as it was “primarily directed towards encouraging and developing tourism.”[9]216 So.2d 202. This case is found in Fastcase. The court went on to say that:

[W]e reject the State’s argument that the powers granted the District are commensurate in scope with those characteristic of a local municipal government rendering the enabling act a mere subterfuge to avoid the creation of a municipality. Nor can we accept the view advanced by the State that the enabling act embraces an unlawful attempt to delegate the taxing power of the state or that the same is tantamount to a gross abuse of legislative authority. The taxing provisions contained in Ch. 67–764 contain sufficient limitations to absolve them from the charge that they are unlawful delegations of authority.

The ruling upheld RCID’s legitimacy.

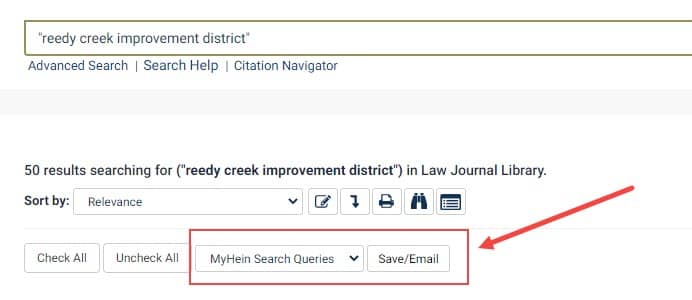

Whether the Reedy Creek Improvement District will actually be dissolved next year is something not even the astute researchers at HeinOnline can predict. What will happen to the District’s debt, and what its dissolution would ultimately mean for day-to-day operations at Walt Disney World, is up for pundits to debate and for time to ultimately tell. No doubt the outcome of the current Reedy Creek situation will inspire many future law review articles. You can make sure you are notified when new content on this is added to HeinOnline by saving the search query “reedy creek improvement district” to your MyHein account. You will be notified via email when new content is added to HeinOnline that matches this query string.

Make sure you are subscribed to the HeinOnline Blog as HeinOnline editors have their own search queries saved to write a follow-up post on this developing situation.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1, ↑4, ↑6 | Chad D. Emerson, Merging Public and Private Governance: How Disney’s Reedy Creek Improvement District Re-Imagined the Traditional Division of Local Regulatory Powers, 36 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 177 (2009). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑3, ↑5 | Todd William Gretton, Responsible Corporate Environmental Policy: Available in Fantasyland; Coming Soon to Main Street U.S.A. – A Glimpse at a Corporate Owned and Operated Special Purpose District and Its Impact on the Environment in Central Florida, 15 Penn St. Envtl. L. Rev. 151 (2006). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑7, ↑9 | 216 So.2d 202. This case is found in Fastcase. |

| ↑8 | Kent Wetherell, Florida Law because of and According to Mickey: The Top 5 Florida Cases and Statutes Involving Walt Disney World, 4 Fla. Coastal L.J. 1 (2002). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |