Many of us know the names of Sandra Day O’Connor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Harriet Tubman, but there are countless other women who have played significant roles in advancing women’s rights and social status throughout history. In this blog post, we will highlight four lesser-known women who may not have received widespread recognition but have undoubtedly made a lasting impact on the world.

1. Patsy Takemoto Mink

Patsy Takemoto Mink was a third-generation Japanese American attorney and politician from Hawaii. She applied to Columbia University but was immediately rejected. However, she was admitted to the University of Chicago in order to fill their “foreign student quota.” Due to the loss of her Hawaiian territorial residency upon marriage, Mink was initially prevented from taking the bar exam. She decided to challenge the statute[1]Paul Igasaki, Patsy Takemoto Mink, 29 HUM. Rts. 25 (2002). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library and was ultimately successful in doing so. As a result, she was able to take the bar exam and passed. What’s more, Mink was the first woman from Hawaii to serve in Congress. Out of the 21 women who ran for office in the election to the House in 1964, Mink was the only one who emerged victorious.[2]Dorothy M. Orsini, Report of NAWL Delegate to House of Delegates, American Bar Association – August 10-14, 1964, 51 WOMEN LAW. J. 18 (1965). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library

While in office, Mink authored Hawaii’s “equal pay for equal work” law[3]Patsy Mink: A Biography by Esther K. Arinaga and Rene E. Ojiri, with a forward by Eric K. Yamamoto and Tania Cruz, 4 APLPJ 569 (2003). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library in 1957. She also spoke out against the Vietnam War[4]Patsy Mink: A Biography by Esther K. Arinaga and Rene E. Ojiri, with a forward by Eric K. Yamamoto and Tania Cruz, 4 APLPJ 569 (2003). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library early on, condemning the conflict as immoral. She emphasized the negative impact of diverting funds from domestic programs towards the war effort. Mink was also a strong advocate for the rights of immigrants, people of color, labor union members, and individuals from low-income backgrounds. She played an instrumental role in sponsoring important women’s rights legislation, such as the Child Care Development Act of 1971 and the Education Amendments of 1972,[5]To amend the Higher Education Act of 1965, the Vocational Education Act of 1963, the General Education Provisions Act (creating a National Foundation for Postsecondary Education and a National Institute of Education), the Elementary and Secondary … Continue reading which included Title IX.

I am here to remind you that you have an enormous responsibility in the legislative field because when the United States Supreme Court fails the women of America and the minorities of America, it is the Legislative Branch, the Congress, that has to rescue this nation.

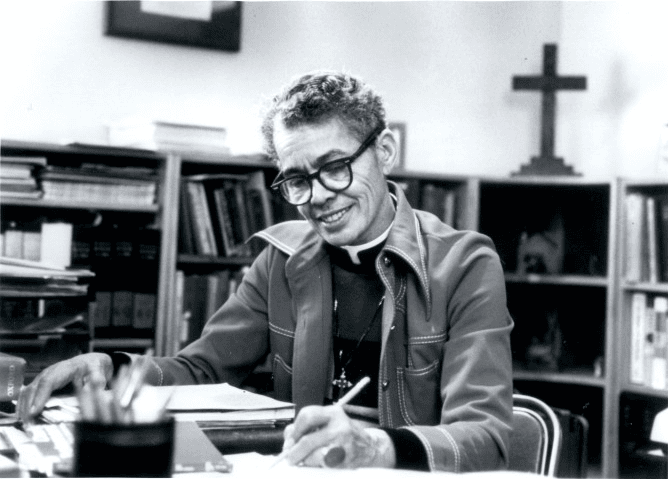

2. Reverend Pauli Murray

Rev. Pauli Murray, an American civil rights activist, author, lawyer, and gender equality advocate, pursued her passion for the ministry and made history in 1977 by becoming the first African-American woman and one of the first women to be ordained as an Episcopal priest. Murray’s sexual and gender identity did not conform to the prevailing social norms of her time. In her youth, she occasionally presented herself as a teenage boy. In retrospect, some scholars have categorized Murray as transgender,[6]Florence Wagman Roisman, Lessons for Advocacy from the Life and Legacy of the Reverend Doctor Pauli Murray, 20 U. MD. L.J. RACE, RELIGION, GENDER & Class 1 (2020). This article can be found in … Continue reading and many believe this is why she was considered overlooked in the history of civil rights.

Despite graduating as the top student in her class, Murray was refused the opportunity[7]Mary Elizabeth Basile, Pauli Murray’s Campaign against Harvard Law School’s Jane Crow Admissions Policy , 57 J. LEGAL EDUC. 77 (2007). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library to pursue post-graduate studies at Harvard University due to her gender. Over the years, she questioned Harvard’s policy repeatedly, hoping to bring change. She also was a civil rights activist who at one point was arrested for refusing to relinquish her seat on a bus which was designated for white people only.[8]Paul L. Edenfield, American Heartbreak: The Life of Pauli Murray, 27 LEGAL Stud. F. 733 (2003). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library However, what many are unaware of is that she made a significant contribution to the civil rights movement by establishing the groundwork[9]Michele Goodwin, Lessons in Race and Racism in the Legal Academy: Notes on Pauli Murray, 73 Rutgers U.L. REV. 913 (2021). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library for the argument that was presented in Brown v. Board with the help of one of her academic publications. Murray is also known for coining the term “Jane Crow”[10]Pauli Murray & Mary O. Eastwood, Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII , 34 GEO. Wash. L. REV. 232 (1965). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library and has been credited by Ruth Bader Ginsburg for influencing the work for gender equality by formulating the argument that the Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause applied to woman.

Descendant of slave and of slaver owner…. Now I was empowered to minister the sacrament of One in whom there is no north or south, no black or white, no male or female—only the spirit of love and reconciliation drawing us all toward the goal of human wholeness.

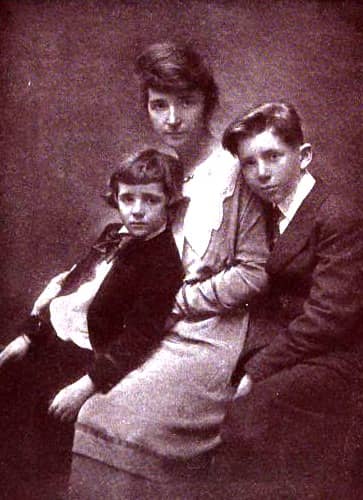

3. Margaret Sanger

Margaret Sanger, a nurse and social worker on the East Side in New York City, became passionate about birth control issues in 1912. During her work, Sanger encountered working-class immigrant women who experienced frequent childbirth, miscarriages, and self-induced abortions due to a lack of knowledge about how to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Access to information on contraception was restricted due to the Comstock laws[11]R. Alta Charo, The Interaction between Family Planning Policy and the Introduction of New Reproductive Technologies, 11 LAW CONTEXT: A Socio-LEGAL J. 58 (1993). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library and a multitude of state laws on the basis of obscenity.

Sanger established the first family planning and birth control clinic in 1916 in Brooklyn. However, she was arrested just nine days after opening the clinic, and her bail was set at $500. Despite this setback, Sanger continued to see some patients until the police returned and arrested her and her sister, Ethel Byrne, for violating a New York state law that banned the distribution of contraceptives. Her clinic was subsequently closed because Sanger was not a licensed physician. Birth control advocates emerged victorious as the Court of Appeals[12]People v. Sanger, 222 N.Y. 192. January 8, 1918. This case can be found within HeinOnline’s integration with Fastcase broadly interpreted the term “disease” in the statute. This enabled physicians to safely and legally prescribe contraceptives without fear of criminal prosecution. Sanger continued to push boundaries. In 1932, she deliberately ordered a diaphragm from Japan in order to provoke a legal battle. The U.S. government confiscated the diaphragm, but Sanger’s subsequent legal challenge resulted in a 1936 court ruling[13]United States v. One Package, 86 F.2d 737. December 7, 1936. This case can be found within HeinOnline’s integration with Fastcase that overturned a significant provision of the Comstock laws that banned doctors from obtaining contraceptives.

To get a more personal insight into Sanger’s life, check out her autobiography.[14]Margaret Sanger. Margaret Sanger: An Autobiography (1938). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law database

I knew something must be done to rescue those women who were voiceless; someone had to express with white hot intensity the conviction that they must be empowered to decide for themselves when they should fulfill the supreme function of motherhood.

4. Eunice Carter

Eunice Carter announced at the age of eight that she wanted to be a lawyer so she could put bad people in jail,[15]Russell Fowler, Eunice Carter: Trailblazing Lawyer, 55 TENN. B.J. 28 (2019). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library and that’s just what she did. Carter was among the first African-American women to practice law in New York and served as one of the first African-American prosecutors in the United States. She played an active role in the Pan-African Congress and United Nations’ committees aimed at promoting women’s status globally. She also spearheaded a significant investigation into prostitution racketeering, developing a case and plan that enabled the prosecution of the notorious Mafia leader Charles “Lucky” Luciano for forced prostitution.

What’s more, Carter was very active in the International Council of Women where she often spoke at human rights conventions.[16]159 (1967) Human rights conventions. Hearings before a subcommittee of the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, Ninetieth Congress, first session. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database A fearless leader of her time, she journeyed across the globe and openly denounced fascism, communism, the Mafia, and the Ku Klux Klan.

However, there is the fact that we need not and should not sit back in the snug security of our own professed righteousness but should fulfill our moral obligation to the rest of the world by setting an example in ratifying these conventions.

Women and the Law: A Legacy of Progress

This Women’s History Month, explore HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy), a database that brings together thousands of books, biographies, and periodicals that allow users to research the progression of women’s rights over the past 200 years. Discover primary legal and political sources as well as secondary scholarly analysis of issues such as abortion, women in the workforce, the education of women, women’s suffrage, and more.

Affectionately nicknamed for the grandmother of Hein’s CEO (Margaret “Peggy” Marmion), this database also includes titles from Emory University Law School’s Feminism and Legal Theory Project which provide a platform to view the effect of law and culture on the female gender.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Paul Igasaki, Patsy Takemoto Mink, 29 HUM. Rts. 25 (2002). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Dorothy M. Orsini, Report of NAWL Delegate to House of Delegates, American Bar Association – August 10-14, 1964, 51 WOMEN LAW. J. 18 (1965). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library |

| ↑3, ↑4 | Patsy Mink: A Biography by Esther K. Arinaga and Rene E. Ojiri, with a forward by Eric K. Yamamoto and Tania Cruz, 4 APLPJ 569 (2003). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library |

| ↑5 | To amend the Higher Education Act of 1965, the Vocational Education Act of 1963, the General Education Provisions Act (creating a National Foundation for Postsecondary Education and a National Institute of Education), the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, Public Law 874, Eighty-first Congress, and related Acts, and for other purposes., Public Law 92-318, 92 Congress. 86 Stat. 235 (1972). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database |

| ↑6 | Florence Wagman Roisman, Lessons for Advocacy from the Life and Legacy of the Reverend Doctor Pauli Murray, 20 U. MD. L.J. RACE, RELIGION, GENDER & Class 1 (2020). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library |

| ↑7 | Mary Elizabeth Basile, Pauli Murray’s Campaign against Harvard Law School’s Jane Crow Admissions Policy , 57 J. LEGAL EDUC. 77 (2007). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library |

| ↑8 | Paul L. Edenfield, American Heartbreak: The Life of Pauli Murray, 27 LEGAL Stud. F. 733 (2003). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library |

| ↑9 | Michele Goodwin, Lessons in Race and Racism in the Legal Academy: Notes on Pauli Murray, 73 Rutgers U.L. REV. 913 (2021). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library |

| ↑10 | Pauli Murray & Mary O. Eastwood, Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII , 34 GEO. Wash. L. REV. 232 (1965). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library |

| ↑11 | R. Alta Charo, The Interaction between Family Planning Policy and the Introduction of New Reproductive Technologies, 11 LAW CONTEXT: A Socio-LEGAL J. 58 (1993). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library |

| ↑12 | People v. Sanger, 222 N.Y. 192. January 8, 1918. This case can be found within HeinOnline’s integration with Fastcase |

| ↑13 | United States v. One Package, 86 F.2d 737. December 7, 1936. This case can be found within HeinOnline’s integration with Fastcase |

| ↑14 | Margaret Sanger. Margaret Sanger: An Autobiography (1938). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law database |

| ↑15 | Russell Fowler, Eunice Carter: Trailblazing Lawyer, 55 TENN. B.J. 28 (2019). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library |

| ↑16 | 159 (1967) Human rights conventions. Hearings before a subcommittee of the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, Ninetieth Congress, first session. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database |