Loyal readers of the HeinOnline Blog are used to posts that dive deep into some of history’s most famous moments, pulling up primary sources and authoritative secondary sources to tell stories about presidents, wars, and disasters. Today, however, we are going to explore one of history’s weirder and lesser-known tales: the 18th century Gin Craze.

Dutch Courage Comes to England

Modern gin originated in The Netherlands. Popular lore generally credits the Eighty Years’ War[1]Henry Smith Williams. Historians’ History of the World (1904). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated. with introducing gin to the English palate; soldiers serving in The Netherlands would swig a dram of genever before battle, bringing a taste for the distilled liquor home with them. Gin’s popularity[2]Jessica Warner, The Naturalization of Beer and Gin in Early Modern England, 24 Contemp. Drug Probs. 373 (1997). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. took off in the mid-1600s with improvements in its distillation process, allowing for mass-market production.

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 deposed James II and installed William III of Orange as King of England, Ireland, and Scotland. The Glorious Revolution, in terrifically simplified terms, overthrew James II, a Catholic, and replaced him with his Protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch husband, William, at a time when tensions between Catholics and Protestants in England were murderously high.

Almost immediately after the Glorious Revolution, William III prohibited the importation of French brandy.[3]William Phillips, The Smugglers, 1966 B.T.R. 28 (1966). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. With the upper classes deprived of their drink of choice, English distilleries flourished. Landowning members of Parliament stood to gain from the distillation boom, as gin production was “providing a much-needed market for the nation’s surplus grain.”[4]Jessica Warner, The Naturalization of Beer and Gin in Early Modern England, 24 Contemp. Drug Probs. 373 (1997). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Lucrative tax incentives[5]Arthur Shadwell. Drink, Temperance and Legislation (1915). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. were given to local distillers. It was shockingly effective: in 1684, before the Glorious Revolution, 527,000 gallons of spirits were produced in England; by 1714, 2 million gallons were produced; by 1735, production had climbed to 5,394,000 gallons, and in 1742, it had reached an astonishing 7,160,000 gallons.[6]Arthur Shadwell. Drink, Temperance and Legislation (1915). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics.

England Goes Crazy for Gin

Of course, distillers weren’t producing all this gin just for fun. Now cheaper than beer,[7]Randy Beck, Popular Enforcement of Controversial Legislation, 57 Wake Forest L. Rev. 553 (2022). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. gin became the drink of choice for the lower classes, and consumption skyrocketed to excessive proportions. In 1704, Daniel Defoe, of Robinson Crusoe fame, wrote:[8]Arthur Shadwell. Drink, Temperance and Legislation (1915). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics.

By 1725, a committee of magistrates in Middlesex, a county in the greater London area, estimated that there were 6,187 retail establishments selling “geneva or other strong waters”[9]George Ranken Askwith. British Taverns, Their History and Laws (1928). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. in an area where the population was about 700,000 people. By 1739, a separate report estimated that number had grown to 8,659 shops, in addition to 5,975 ale-houses. Many accounts of this time report one notorious advertisement displayed at a gin shop: “Drunk for 1 penny, dead drunk for 2 pennies, clean straw for nothing.”[10]W. Eden Hooper, Compiler. Central Criminal Court of London: Being a Survey of the History of the Court and of Newgate, the Fleet and Other Jails (1909). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials.

Not surprisingly, there was an increase in public drunkenness, theft, and murder. Upper class lawmakers and commentators watched the crisis they had helped manufacture with horror. In the midst of this, gin earned a new, notorious nickname, mother’s ruin,[11]131 J.P.N. 415 (1967). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. most likely derived from tales of drunken mothers neglecting and even killing their children. In 1736, Mary Estwick, an elderly woman, was hired to take care of a toddler named Mary Graves, who tragically burned to death in Estwick’s care. Witnesses reported that Estwick was “quite intoxicated with Gin”[12]Jessica Warner, Old and in the Way: Widows, Witches, and Spontaneous Combustion in the Age of Reason, 23 Contemp. Drug Probs. 197 (1996). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. at the time of little Mary’s death, and was so intoxicated that neighbors who rushed in to extinguish the flames could not wake her up, nor could she remember the events leading up to Mary’s death. One modern day commentator described the moral panic thus: “Anti-gin propagandists claimed that gin-swilling mothers and nursemaids were neglecting children and thus the next generations of soldiers, sailors, and labourers. Solving the gin problem would restore the hierarchies of class and gender.”[13]Simon Flacks, Dangerous Drugs, Dangerous Mothers: Gender, Responsibility and the Problematisation of Parental Substance Use, 39 Critical Soc. Pol’y 477 (2019). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal … Continue reading

The Gin Acts

Parliament first attempted to sober up the nation in 1729 by levying heavier taxes on gin and requiring licenses for retailers. Openly hawking gin in the street was also prohibited. To skirt the act, entrepreneurial drunkards manufactured “Parliament Brandy,”[14]Stephen Dowell. History of Taxation and Taxes in England from the Earliest Times to the Present Day (1884). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Taxation & Economic Reform in America. which was neither gin nor brandy, but did technically fall outside the scope of the act, and could be sold without a license. Ineffective, the act was repealed in 1733. But reformers did not give up, passing the Gin Act 1736, which levied such exorbitant taxes on gin as to make it practically unattainable.

Riots[15]William Cobbett. Cobbett’s Parliamentary History of England from the Norman Conquest, in 1066 to the Year 1803 (1733-1737). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. broke out at the Act’s passage, and armed soldiers were stationed outside the home of the Act’s author, Sir Joseph Jekyll.[16]Philip C. Yorke. Life and Correspondence of Philip Yorke, Earl of Hardwicke, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain (1913). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. Rather than curing the kingdom of its thirst for gin, the Act drove the gin trade underground, where it flourished. Consumption of gin[17]Arthur Shadwell. Drink, Temperance and Legislation (1915). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. in England and Wales was estimated at 11 million gallons in 1733; by 1742, it had soared to 20 million gallons. Not surprisingly, the 1736 Act was repealed, and replaced by the Gin Act 1743,[18]Nathaniel Chapman. Select Speeches, Forensick and Parliamentary, with Prefatory Remarks (1808). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. which was just as ineffective as its two predecessors.

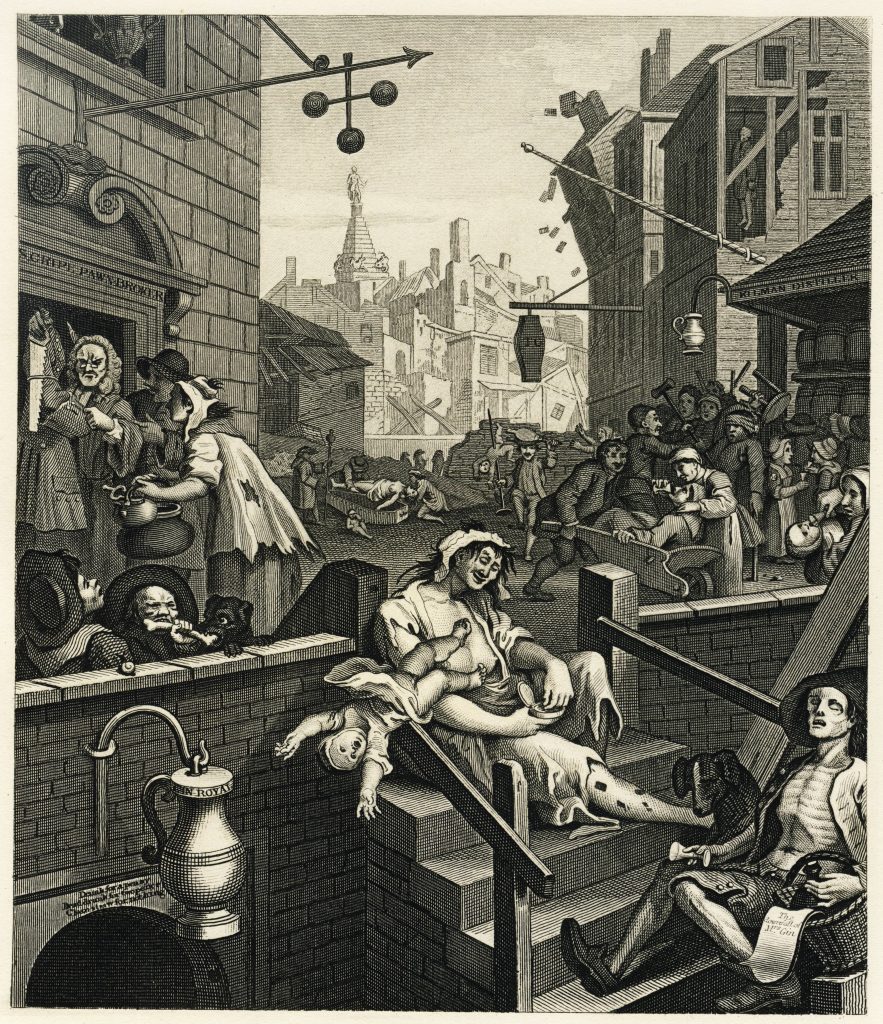

Perhaps one of the most famous depictions of the debauchery and suffering caused by the gin craze is William Hogarth’s 1751 engraving Gin Lane. Hogarth was an artist, satirist, and journalist, whose art often depicted the brutality of metropolitan life. In the foreground of Gin Lane sits a mother, her legs riddled with syphilitic sores, so drunk she is unaware that her baby is falling to his death. All around her are scenes more and more horrific: carpenters pawn their tools for money to drink, people fight with dogs for bones to eat, another mother gives her infant a dram of gin. The infamous gin advertisement of dead drunk and clean straw is also reproduced.

Hogarth released a contrasting companion print with Gin Lane. Titled Beer Street, it shows revelers who are well-fed and happy. Workers enjoy a pint after finishing a hard day’s work. There is no death or depravity in Beer Street, signifying the “purer” national beverage everyone should be enjoying.

Hogarth released his prints to support the Gin Act 1751. Like previous laws, the 1751 Act required licenses[19]Arthur Shadwell. Drink, Temperance and Legislation (1915). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. for selling gin but did away with prohibitory taxes. Distillers could not sell gin themselves and could only sell to licensed retailers. Fresh licensing requirements for retailers were also required, but again were less harsh than those under the 1736 Act. The moderate approach succeeded in tempering the gin crisis. Beer drinking increased and gin fell out of favor. Between 1760 and 1782, consumption of gin and other spirits had leveled out in England and Wales, dropping to an average of 4 million gallons.[20]George Ranken Askwith. British Taverns, Their History and Laws (1928). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics.

Research, Served Neat

Whether you like it shaken or stirred, HeinOnline offers an unparalleled concoction of resources for all your research needs. Get intoxicated on knowledge by subscribing to the HeinOnline Blog and keep up to date on all things Hein.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Henry Smith Williams. Historians’ History of the World (1904). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑4 | Jessica Warner, The Naturalization of Beer and Gin in Early Modern England, 24 Contemp. Drug Probs. 373 (1997). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑3 | William Phillips, The Smugglers, 1966 B.T.R. 28 (1966). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑5, ↑6, ↑8, ↑17, ↑19 | Arthur Shadwell. Drink, Temperance and Legislation (1915). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑7 | Randy Beck, Popular Enforcement of Controversial Legislation, 57 Wake Forest L. Rev. 553 (2022). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑9, ↑20 | George Ranken Askwith. British Taverns, Their History and Laws (1928). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑10 | W. Eden Hooper, Compiler. Central Criminal Court of London: Being a Survey of the History of the Court and of Newgate, the Fleet and Other Jails (1909). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. |

| ↑11 | 131 J.P.N. 415 (1967). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑12 | Jessica Warner, Old and in the Way: Widows, Witches, and Spontaneous Combustion in the Age of Reason, 23 Contemp. Drug Probs. 197 (1996). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑13 | Simon Flacks, Dangerous Drugs, Dangerous Mothers: Gender, Responsibility and the Problematisation of Parental Substance Use, 39 Critical Soc. Pol’y 477 (2019). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑14 | Stephen Dowell. History of Taxation and Taxes in England from the Earliest Times to the Present Day (1884). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Taxation & Economic Reform in America. |

| ↑15 | William Cobbett. Cobbett’s Parliamentary History of England from the Norman Conquest, in 1066 to the Year 1803 (1733-1737). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑16 | Philip C. Yorke. Life and Correspondence of Philip Yorke, Earl of Hardwicke, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain (1913). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. |

| ↑18 | Nathaniel Chapman. Select Speeches, Forensick and Parliamentary, with Prefatory Remarks (1808). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Trials. |