Every presidential election matters. But the election of 1876 had repercussions that still reverberate today. Barely a decade after the end of the American Civil War, the country was in a precarious state. Outgoing President Ulysses S. Grant’s time in the White House had been marred by rampant scandal and corruption.[1]William B. Hesseltine. Ulysses S. Grant, Politician (1957). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. The economy groaned under an ongoing worldwide financial crisis, known as the Panic of 1873.[2]David Kinley. Independent Treasury of the United States and Its Relations to the Banks of the Country (1910). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Taxation & Economic Reform in America. For ten years, Reconstruction policies had attempted to both remake and reshape the Union, by reintegrating former Confederate states, physically rebuilding their infrastructure, and granting equal civil rights—including the vote—to formerly enslaved people. This was the environment in which voters went to the polls to pick a new president—one of anxiety, unease, and rapid change. Those feelings would only intensify after Election Day.

The Candidates

For the Republican Party

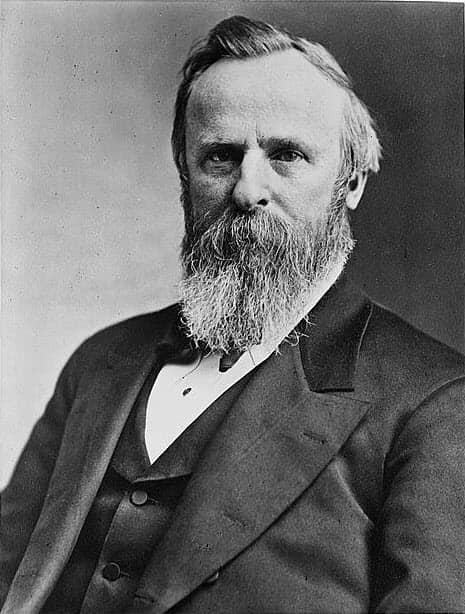

The Republican Party had held the White House for the last three presidencies, in Abraham Lincoln (1861–1865), Andrew Johnson (1865–1869), and Ulysses S. Grant (1869–1877). The party initially set its hopes on James G. Blaine,[3]Hugh Craig. Biography and Public Services of Hon. James G. Blain, Giving a Full Account of Twenty Years in the National Capital (1884). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. former Speaker of the House and Representative from Maine, to keep the streak alive. But a railroad bond scandal and a Congressional investigation into Blaine’s business affairs[4]Mr. Blaine’s Record: The Investigation of 1876 and the Mulligan Letters (1884). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. soured Blaine’s chances. Still, Blaine had significant support going into the Republication convention. After seven ballots, however, it was Ohio governor Rutherford B. Hayes[5]William Dean Howells. Sketch of the Life and Character of Rutherford B. Hayes, Also a Biographical Sketch of William A. Wheeler, with Portraits of Both Candidates (1876). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. who won the nomination.

For the Democratic Party

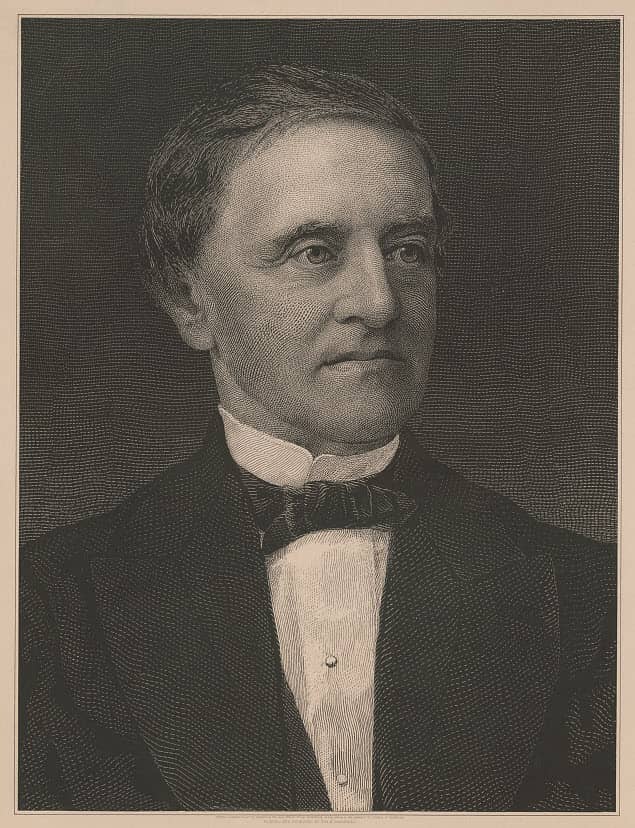

Democrats had taken control of the House of Representatives in 1874 for the first time in sixteen years, thanks to a strong midterm showing; 35 states held elections in 1874 and 23 went Democratic,[6]Paul Leland Haworth. Hayes-Tilden Disputed Presidential Election of 1876 (1906). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. including Republican strongholds like Ohio and Massachusetts. Hoping that public discontent with the Grant administration would put a Democrat in the White House, the party nominated New York governor Samuel J. Tilden.[7]John Bigelow. Life of Samuel J. Tilden (1895). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. Tilden played an important role in indicting infamous political boss William Tweed,[8]James Sullivan, Editor. History of New York State 1523-1927 (1927). This book is found in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. and he ran his presidential campaign on a strong anti-corruption platform.

The Campaign

Violence and Voting in the 1870s

Elections in the Reconstruction era were far from free, fair, and safe. The 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, granted Black men the right to vote. They overwhelmingly registered as Republicans, the party of Lincoln, and the party that had freed them from slavery. Black men enthusiastically exercised their new civil rights and even held elected office; in 1870, Hiram Revels[9]Ida A. Brudnick & Jennifer E. Manning. African American Members of the U.S. Congress: 1870–2020 (2020). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. became the first Black Congressman, representing Mississippi in the Senate. At the same time, up until 1872,[10]Public Law 42-194. 17 Stat. 142 (1872). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. most former Confederates, from political leaders to generals to privates, were barred from voting and holding political office.

Despite the protection of a constitutional amendment, violence and intimidation towards Black Americans throughout the Southern states was so rampant that in 1870 Congress passed a series of Enforcement Acts, which allowed the government to use federal troops to protect citizens’ right to vote and made voter intimidation a felony. These threats were real, organized, and open. One of the most infamous examples is the Mississippi Plan.[11]Carroll Rhodes, Changing the Constitutional Guarantee of Voting Rights from Color-Conscious to Color-Blind: Judicial Activism by the Rehnquist Court, 16 Miss. C. L. Rev. 309 (1996). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law … Continue reading Created in 1874, the plan was a strategy used by the Democratic Party to overthrow the state’s Republican Party and retake control of the state legislature and governor’s office. Armed white supremacist groups like the Red Shirts prevented Black men from voting in Vicksburg and assassinated the county’s Black sheriff.

Throughout the South, the chief threat to Black Americans’ civil rights was the then newly formed Ku Klux Klan.[12]Elaine Frantz Parsons. Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan during Reconstruction (2015). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Civil Rights & Social Justice. The Klan’s threat to Black Americans’ lives, safety, and civil rights was so severe and so inadequately addressed at the state level that in 1871, at Grant’s urging, the Ku Klux Klan Act[13]Public Law 42-22. 17 Stat. 13 (1871). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large.was passed. The act empowered the President to declare martial law when states failed to protect their citizens’ constitutional rights and to suspend the writ of habeus corpus. Grant’s administration so aggressively used the act to prosecute Klansmen that the Klan was effectively dismantled by the end of the decade,[14]Robert F. Bartle, The Red Summer: The Awakening of Black America, 22 Neb. Law. 59 (2019). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Bar Journals Library. at least until its resurgence in the early 20th century. The Ku Klux Klan Act is still in effect today.

Trouble at the Polls

Both Hayes and Tilden waged bitter campaigns. The Tilden campaign wanted the public to not forget the Grant administration’s scandals, while the Hayes campaign explicitly identified the Democratic party with the Confederacy.[15]Paul Leland Haworth. Hayes-Tilden Disputed Presidential Election of 1876 (1906). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. Both campaigns likely actively undermined the election’s integrity, given widespread allegations of voter intimidation, violence, and fraud.

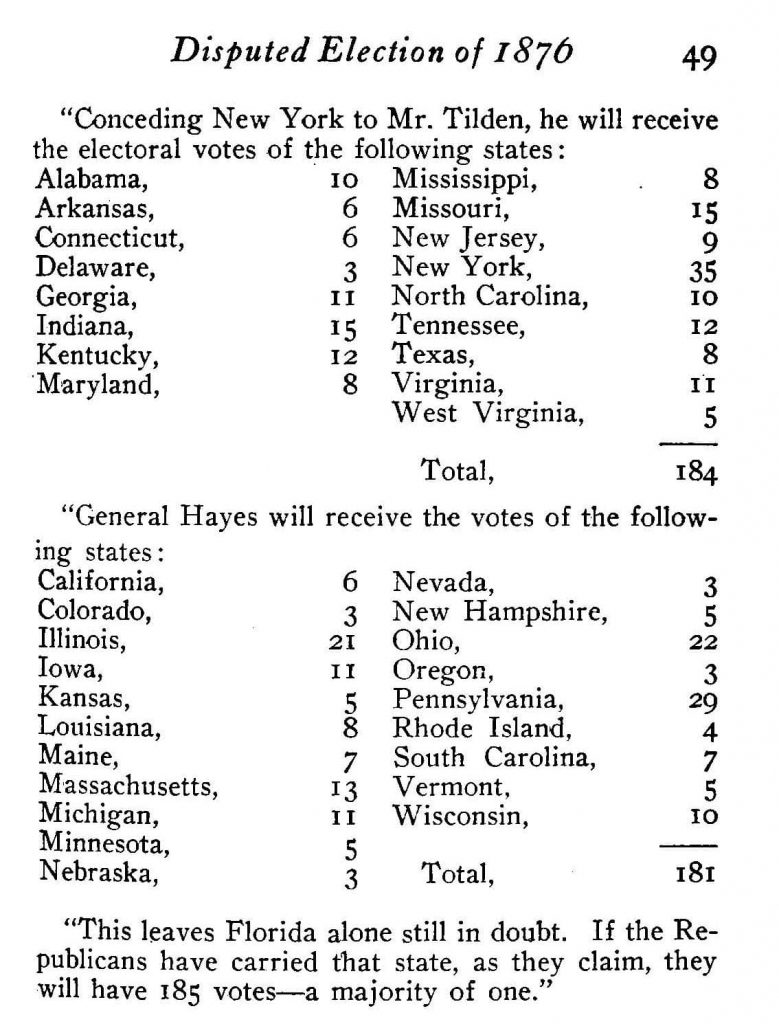

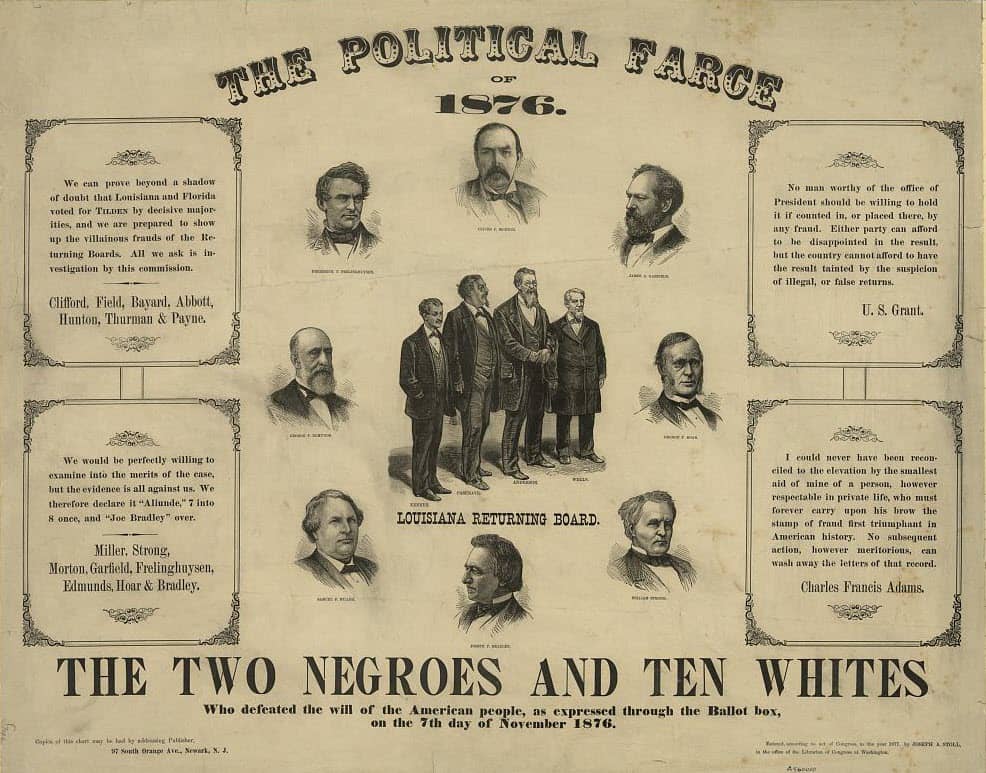

When the votes were tallied on election day, Tilden had won the popular vote by 200,000 votes[16]Christopher Anglim, Selective, Annotated Bibliography on the Electoral College: Its Creation, History, and Prospects for Reform, 85 Law Libr. J. 297 (1993). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.—but was one electoral vote shy of victory. Suspiciously, double returns[17]Christopher Anglim, Selective, Annotated Bibliography on the Electoral College: Its Creation, History, and Prospects for Reform, 85 Law Libr. J. 297 (1993). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. were sent in from Republican-controlled Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina, bringing their votes into question. If Hayes was awarded their electoral votes, he would win the presidency. Further compounding claims of collusion, Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina were the only states from the former Confederacy that were still occupied by federal troops. It would later be argued that,[18]Andrew Cunningham McLaughlin. Constitutional History of the United States (1935). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated. by virtue of their military occupation, elections in these states inherently could not be fair, as voters were required to pass by armed troops on their way to the polls.

Picking a President

The Electoral Commission

To resolve the returns from Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina, Congress passed the Electoral Commission Act in January 1877.[19]Public Law 44-37. 19 Stat. 227 (1877). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. The 15-member commission[20]5 Cong. Rec. 1 (1877). The Commission’s full proceedings can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. was made up of seven Democrats and eight Republicans. Throughout the month of February, they heard arguments from lawyers representing Tilden and Hayes. Hayes’ lawyers argued that Congress and the Commission could not refuse returns that had been certified by the states,[21]John William Burgess. Reconstruction and the Constitution 1866-1876 (1902). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated. as it would undermine state sovereignty. The Commission agreed and awarded Hayes the disputed electoral votes along a party-line vote. It gave him the presidency by one electoral vote.

Filibuster

The Electoral Commission’s decision was final unless both the House and Senate rejected it; with the Senate controlled by the Republican party, this outcome was doubtful. Many Democrats, however, were convinced Tilden was being cheated out of the presidency. There were calls for an armed uprising to prevent Hayes’ inauguration. As a last resort, some House Democrats objected to Vermont’s electoral votes, threatening to filibuster the electoral certification until past inauguration day. The filibuster, however, ended after eighteen hours,[22]Paul Leland Haworth. Hayes-Tilden Disputed Presidential Election of 1876 (1906). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. and Congress finished the electoral count in the pre-dawn hours of March 2, 1877.

The Compromise of 1877

How did a deeply divided Congress, with each faction earnestly believing that their man was the rightful president, peacefully declare Hayes president? The evaporation of Southern Democrats’ staunch belief in Tilden’s legitimacy as the next president is today known as the Compromise of 1877 or the Wormley Agreement.

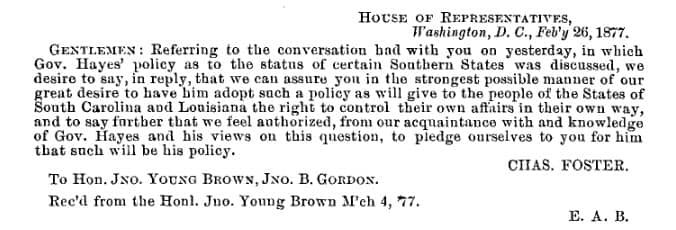

While the Electoral Commission heard arguments, on February 26th multiple conferences took place between Democrats and Republicans. These meetings were held on Capitol Hill and at the Wormley Hotel, a chic Washington hotel owned by James Wormley, a Black man. The exact nature of these discussions is lost to history, but their essence was this: give Hayes the presidency, and federal troops would be withdrawn from the South. Southern states would be allowed to govern however they saw fit without interference.

Whether an actual backroom deal between Democrats and Republicans ever took place—and whether such a meeting had more nefarious motives about reshaping the country’s racial future—today is up to debate.[24]John Copeland Nagle, How Not to Count Votes, 104 Colum. L. Rev. 1732 (2004). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. The result, however, was that Rutherford B. Hayes was sworn in as the nineteenth president while having dinner with the Grants only hours after the electoral count had finished.[25]Paul Leland Haworth. Hayes-Tilden Disputed Presidential Election of 1876 (1906). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. Federal troops were withdrawn from Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, and Reconstruction officially ended.[26]Andrew Cunningham McLaughlin. Constitutional History of the United States (1935). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated.

Aftermath of Compromise

The end of Reconstruction was devastating for Black Southerners. With federal troops gone, Southern Democrats quickly returned to political power. Without staunch federal oversight, Southern states enacted Jim Crow laws designed to dismantle Black Americans’ newly won civil rights. Segregation, otherness, violence, and disenfranchisement would become the daily reality for Black Southerners for the next one hundred years.

Keeping a campaign promise, Hayes only served one term as president. He was succeeded by James A. Garfield,[27]Russell H. Conwell. Life, Speeches, and Public Services of James A. Garfield, Twentieth President of the United States: Including an Account of His Assassination, Lingering Pain, Death, and Burial (1881). This book is found in … Continue reading who coincidentally had been one of the Republican members of the Electoral Commission that had certified Hayes as president. Garfield was assassinated six months into his own presidential term.

Voting Rights & Election Law

Free and fair elections are the lifeblood of any democracy. Are you ready to go to the polls in the 2024 presidential election? Learn about the nuances and complexities of elections and voting systems both in America and across the globe with HeinOnline’s Voting Rights & Election Law database. Featuring thousands of subject-coded titles covering topics ranging from absentee voting to voting rights, this database offers unparalleled access to information surrounding historical and recent elections at both the federal and local levels.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | William B. Hesseltine. Ulysses S. Grant, Politician (1957). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | David Kinley. Independent Treasury of the United States and Its Relations to the Banks of the Country (1910). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Taxation & Economic Reform in America. |

| ↑3 | Hugh Craig. Biography and Public Services of Hon. James G. Blain, Giving a Full Account of Twenty Years in the National Capital (1884). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. |

| ↑4 | Mr. Blaine’s Record: The Investigation of 1876 and the Mulligan Letters (1884). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑5 | William Dean Howells. Sketch of the Life and Character of Rutherford B. Hayes, Also a Biographical Sketch of William A. Wheeler, with Portraits of Both Candidates (1876). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑6, ↑15, ↑22, ↑25 | Paul Leland Haworth. Hayes-Tilden Disputed Presidential Election of 1876 (1906). This book is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑7 | John Bigelow. Life of Samuel J. Tilden (1895). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑8 | James Sullivan, Editor. History of New York State 1523-1927 (1927). This book is found in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. |

| ↑9 | Ida A. Brudnick & Jennifer E. Manning. African American Members of the U.S. Congress: 1870–2020 (2020). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. |

| ↑10 | Public Law 42-194. 17 Stat. 142 (1872). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑11 | Carroll Rhodes, Changing the Constitutional Guarantee of Voting Rights from Color-Conscious to Color-Blind: Judicial Activism by the Rehnquist Court, 16 Miss. C. L. Rev. 309 (1996). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑12 | Elaine Frantz Parsons. Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan during Reconstruction (2015). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Civil Rights & Social Justice. |

| ↑13 | Public Law 42-22. 17 Stat. 13 (1871). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑14 | Robert F. Bartle, The Red Summer: The Awakening of Black America, 22 Neb. Law. 59 (2019). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Bar Journals Library. |

| ↑16, ↑17 | Christopher Anglim, Selective, Annotated Bibliography on the Electoral College: Its Creation, History, and Prospects for Reform, 85 Law Libr. J. 297 (1993). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑18, ↑26 | Andrew Cunningham McLaughlin. Constitutional History of the United States (1935). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated. |

| ↑19 | Public Law 44-37. 19 Stat. 227 (1877). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑20 | 5 Cong. Rec. 1 (1877). The Commission’s full proceedings can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. |

| ↑21 | John William Burgess. Reconstruction and the Constitution 1866-1876 (1902). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated. |

| ↑23 | H.R. Misc. No. 45-31, pt. 2, at 624 (1877). Found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set |

| ↑24 | John Copeland Nagle, How Not to Count Votes, 104 Colum. L. Rev. 1732 (2004). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑27 | Russell H. Conwell. Life, Speeches, and Public Services of James A. Garfield, Twentieth President of the United States: Including an Account of His Assassination, Lingering Pain, Death, and Burial (1881). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. |