In the waning days of World War I in 1918, Eugene Debs, the most famous socialist in America, delivered a speech in Ohio denouncing war. Two weeks later, he was arrested and imprisoned for his words, and sentenced to ten years in federal prison. In 1920, he decided to run for president from his prison cell, ultimately waging the most successful campaign by a socialist candidate in American history.

Keep reading to learn more about the strange election of 1920, and the events that led up to it. To get the most out of this post, make sure you’re subscribed to HeinOnline’s Labor and Employment: The American Worker, U.S. Supreme Court Library, U.S. Statutes at Large, and the Law Journal Library.

The Espionage and Sedition Acts

Eugene Debs’ arrest came at a time of heightened political tension, following years of increasing militarization in the run-up to the United States’ entry into World War I. The Espionage Act[1]To punish acts of interference with the foreign relations, the neutrality, and the foreign commerce of the United States, to punish espionage, and better to enforce the criminal laws of the United States, and for other purposes., Public Law 65-24 / … Continue reading was passed in June 1917, shortly after the United States entered the war. The act made it a crime, punishable by death or imprisonment, to obtain and disseminate information that could be “used to the injury of the United States, or to the advantage of any foreign nation.” Additionally, the act expanded the government’s authority to restrict the distribution of certain materials through the mail, although it stopped short of many of the broad powers President Woodrow Wilson had been publicly calling for since 1915.

The executive branch got many of these powers less than a year later, when the Espionage Act was expanded with the passage of the Sedition Act of 1918,[2]To amend section three, title one, of the Act entitled “An Act to punish acts of interference with the foreign relations, the neutrality, and the foreign commerce of the United States, to punish espionage, and better to enforce the criminal … Continue reading enacted into law in May of 1918, which further extended the powers of the Espionage Act to encompass more categories of previously protected speech. Among other things, the Act prohibited “any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States.” This particular clause would prove to be quite a problem for socialists, anarchists, and other left-wing activists, whose ideology was premised upon the unsuitability of the United States government. In effect, the Act served to criminalize anti-war and anti-capitalist beliefs and speech in the United States for the duration of the war.

The War Over the War

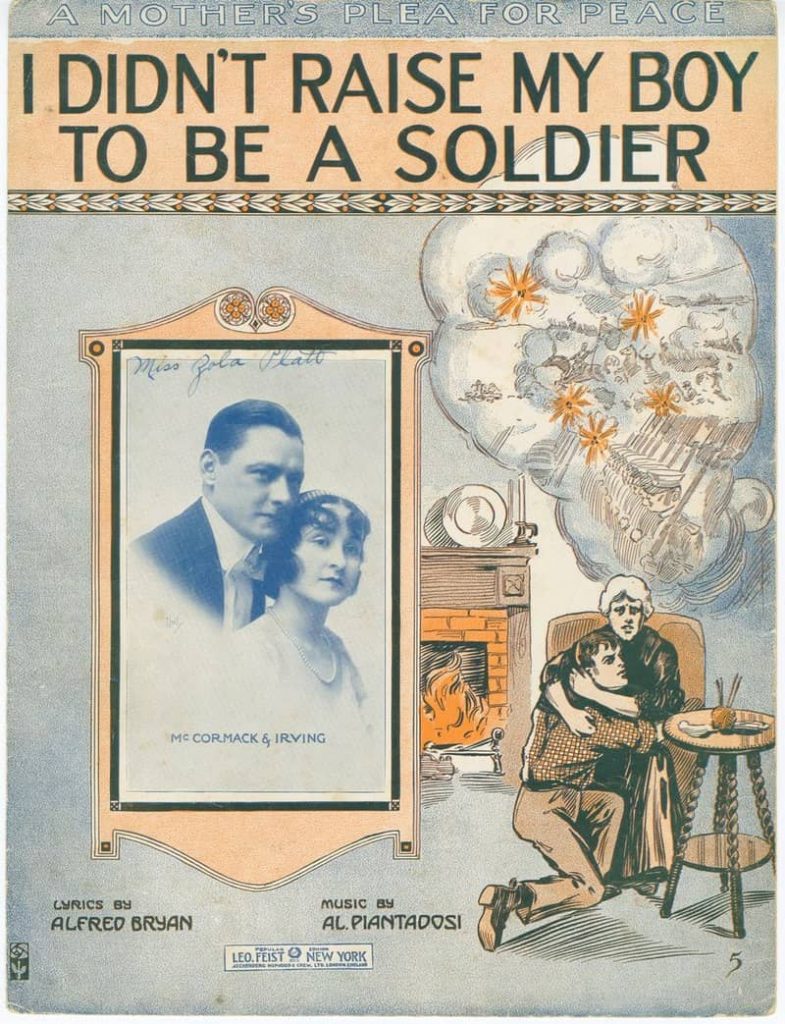

Even before the official entry of the United States in 1917, World War I was a deeply divisive issue in the country. Militant labor activists, socialists, and anarchists were vehement opponents of the war from the start. However, there were also strong anti-war sentiments in the American mainstream as well. One of the most popular songs of 1916 was “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Solider,”[3]D. W. Brogan. Government of the People: A Study in the American Political System (1933). This book is available in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics collection. an anti-war song whose lyrics combined pacifist and proto-feminist suffragist sentiments. The song was an enormous success, with its recording by the Peerless Quartet selling over 650,000 copies.

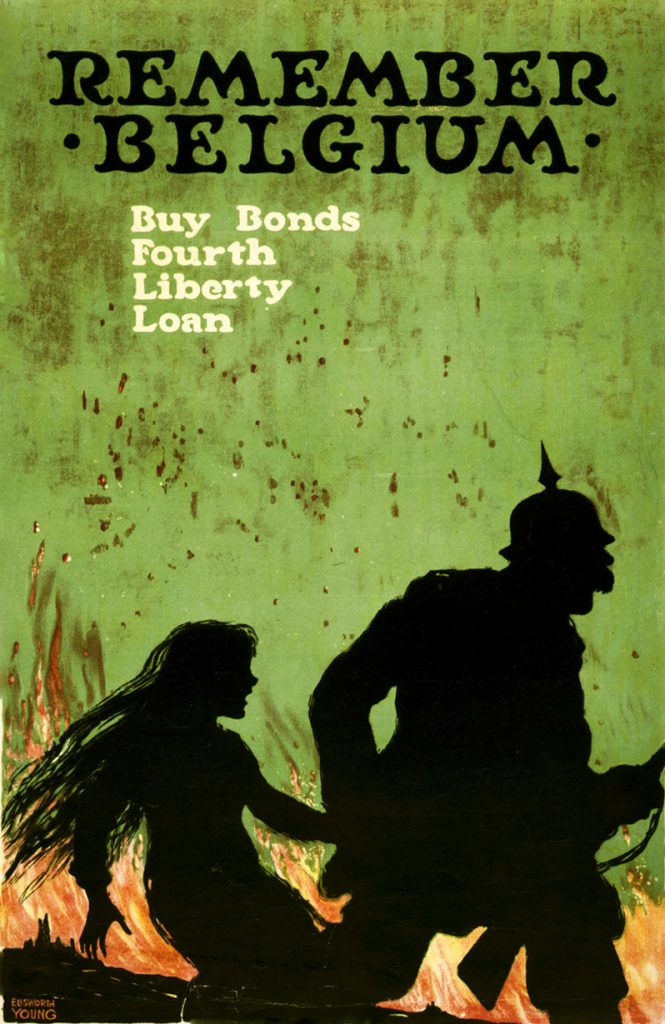

The Wilson Administration, which had long sought to bring the United States into the war, was deeply concerned with the popularity of anti-war media. In addition to amplifying pro-war messaging from the United Kingdom, they made moves to produce and distribute propaganda of their own. In 1917, President Woodrow Wilson established the Committee on Public Education (CPI), which “worked to drum up domestic and foreign support for US involvement in World War I.”[4]G. Alex Sinha, Lies, Gaslighting and Propaganda, 68 BUFF. L. REV. 1037 (2020). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Whereas anti-war propaganda often employed imagery of mothers protecting their children, pro-war propaganda likewise employed evocative and emotive images of women and children[5]Amanda Alexander, The Genesis of the Civilian, 20 LJIL 359 (2007). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. to great effect, portraying the nations of Europe as weak and in need of protection from the depravity of “the Huns,” as propogandists of the time referred to the Germans, in a distinctly orientalist turn of phrase that likewise appealed to American racial prejudices.

Proponents of American entry into the war took more direct measures as well. The 250,000-member vigilante group, the American Protective League,[6]J. Michael Sproule, Clyde Miller: Twentieth Century Pioneer of Free Speech, 24 FREE SPEECH Y.B. 27 (1985). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. coordinated with the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Investigation (the precursor to the modern FBI), to repress anti-war activism and labor organizing.[7]Michael W. Casey & Michael A. Jordan, Free Speech in Time of War: Government Surveillance of the Churches of Christ in World War I, 34 FREE SPEECH Y.B. 102 (1996). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law … Continue reading Civilian vigilantes surveilled and opened the mail of suspected leftists, and even conducted raids upon their homes, with the tacit (and occasionally overt) approval of the authorities. Thousands were arrested, and attacks on anti-war activists in the street were widespread.

It was in this environment, in 1918, that Eugene Debs delivered a speech against the war in Canton, Ohio.

Eugene Debs

By 1918, Eugene Debs was a veteran labor activist and a revered figure in the American left of the era. Debs was born in Indiana in 1855. He dropped out of school at the age of 14, and began working for the Vandalia Railroad. Early in life, he was a member of the Democratic Party, and spent time as a member of the Indiana House of Representatives. Debs came of age during a time of intense strife and militancy in American labor. Debs remained employed by the railroad through the end of the 19th century, where he became involved with union organizing and more radical politics. In 1893, he helped to organize, and was elected as the first president of, the American Railway Union (ARU), which waged a successful strike against the Great Northern Railway in 1894.

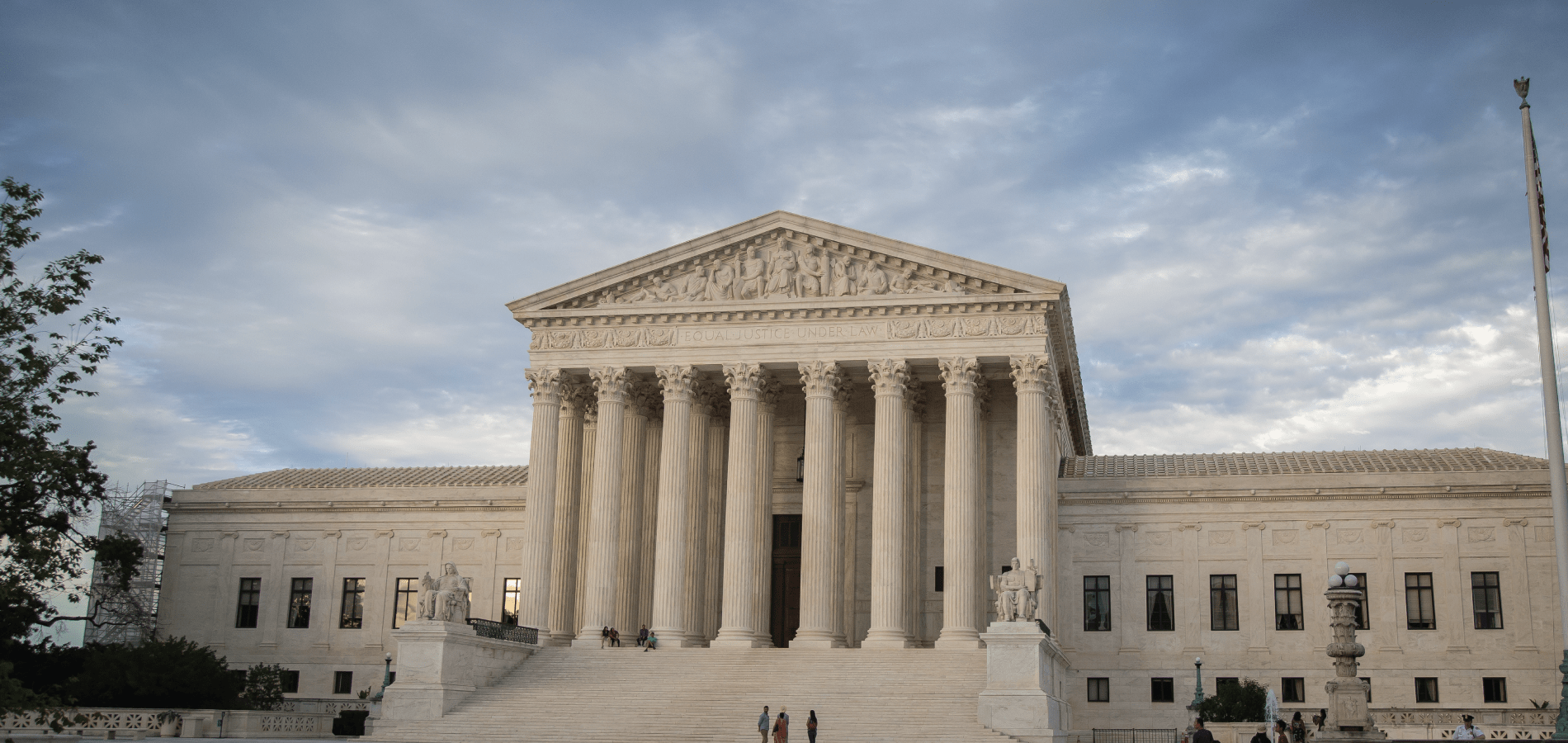

Debs first rose to national prominence later the same year, thanks to his central role in the Pullman Strike.[8]Report on the Chicago Strike of June-July, 1894, by the United States Strike Commission with Appendices Containing Testimony, Proceedings, and Recommendations (1895). This report is available in HeinOnline’s Labor & Employment: The … Continue reading The strike began in 1894 when ARU-represented workers at the Pullman factory in Chicago walked off the job in protest of low wages and poor living conditions. Although Debs initially advised against the walkout—which he viewed as too risky—the ARU ultimately threw its support behind a nationwide boycott, and railroad workers across the nation refused to work on trains containing Pullman cars. The strike was so effective that, between May and June, nationwide rail transport ground to a virtual halt. The economic disruption was so great that, in July, President Grover Cleveland issued an injunction against the work stoppage and called in federal troops to suppress the strike. Clashes broke out, and federal troops and police killed at least 30 railroad workers while suppressing the strike. Debs was arrested and imprisoned for his role in the action. The case later made its way to the United States Supreme Court, in 1895 in In re Debs,[9]In re Debs, Petitioner, 158 U.S. 564, 600 (1895). This case is available in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. which resulted in the Court upholding the injunction against the strike. This would not be Debs’ first appearance before the Court.

After his release from prison, Debs was one of the most important figures in the American labor movement at the turn of the century. He was instrumental in founding the Socialist Party of America and was an early founding member of the radical trade union Industrial Workers of the World.[10]Stein, Emanuel et al. Labor Problems in America (1940). This book is available in HeinOnline’s Labor & Employment: The American Worker. Between 1900 and 1916, Debs ran for president four times: once as the candidate for the Social Democratic Party in 1900; and then as the candidate for the Socialist Party of America in 1904, 1908, and 1912. The last election, which saw the Republican Party split between William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt,[11]H. H. Kohlsaat. From McKinley to Harding: Personal Recollections of Our Presidents (1923). This book is available in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. proved to be the most successful for a socialist candidate in the United States thus far, with Eugene V. Debs and his running mate, Emil Seidel, claiming 6% of the popular vote in the general election. Woodrow Wilson, the victor of the election, would prove to be a tenacious antagonist to American socialists in the years to come.

The Speech, Arrest, and Trial

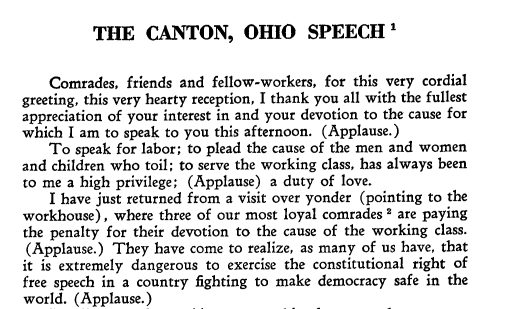

On June 16, 1918, while on his way to the Ohio state Socialist convention in Canton, Debs stopped to deliver a speech outside the Stark County Workhouse, where three local leaders of the Socialist Party were imprisoned for opposing the draft. Debs spent the following two hours speaking in front of a crowd of 1,200, which included plain clothes agents of the Justice Department, who circulated through the crowd demanding to inspect the draft cards of audience members. The Justice Department had also hired a stenographer specifically for the occasion, who frantically recorded Debs’ speech[12]Eugene V. Debs. Writings and Speeches of Eugene V. Debs (1948). This book is available in HeinOnline’s Labor & Employment: The American Worker. during which he, at various times, praised the three imprisoned socialists, denounced the war, denounced the U.S. Supreme Court (which had recently struck down a law against child labor), and generally called for the abolishment of capitalism in the United States and world as a whole.

The speech concluded without incident; Debs continued on to the state convention, and the audience dispersed and returned to their homes. Two weeks later, in Cleveland, Eugene Debs was arrested by U.S. marshals at a Socialist picnic, and charged with ten counts of violating the Espionage Act, as amended by the Sedition Act, during his speech in Canton. Debs’ initial trial took place in September 1918 in Cleveland. Addressing the jury directly, Debs proclaimed, “I have been accused of obstructing the war. I admit it. Gentlemen, I abhor war.”[13]Debs v. United States, 249 U.S. 211, 216 (1919). This case is available in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. Debs was convicted of violating the Espionage Act and sentenced to ten years in federal prison. He appealed the conviction to the Supreme Court of the United States, which heard arguments in 1919.

The Court seized upon Debs’ address to the jury in Cleveland and referenced it in its opinion. Even though Debs did not directly instruct his audience to oppose the draft or obstruct recruitment into the military, the Court concluded that his expressions of sympathy and solidarity for those convicted of doing so amounted to obstruction because his audience could have inferred that they should engage in illegal activity from the tone of his speech. In a unanimous ruling, the Court upheld Debs’ conviction under the Espionage Act.

The next year, the Socialist Party of America nominated Eugene Debs as their candidate for president for the fourth time. After some deliberation, Debs accepted.

The Election of 1920

Campaigning for president from a prison cell presented a number of challenges, notably that Debs, being confined to prison, could not go out and campaign. He was permitted to send out one statement on political issues[14]Eugene V. Debs. Writings and Speeches of Eugene V. Debs (1948). This book is available in HeinOnline’s Labor & Employment: The American Worker. each week, which he wrote by hand and mailed to his home in Terre Haute, Indiana. From there, his wife Kate mailed the letter to the Socialist Party headquarters in Chicago, where it was typeset and distributed to friendly newspapers and party publications.

The process was less than ideal. In many ways, the election of 1920 was a foregone conclusion. Debs did not expect to win, and was more interested in organizing labor unions than electoral politics. For Eugene Debs, the election was a means to an end; for the Socialist Party of America, Eugene Debs was their last hope for a candidate who could unify a socialist labor movement that was becoming increasingly fractured. As Debs himself related, the only people who were surprised by the loss were his fellow prisoners in the federal penitentiary, who had become quite fond of him[15]Eugene V. Debs. Writings and Speeches of Eugene V. Debs (1948). This book is available in HeinOnline’s Labor & Employment: The American Worker. and were very enthusiastic about his campaign.

The Socialist Party received more than 900,000 votes in the election of 1920, for a total of 3.4% of the popular vote. This remains the highest number of votes ever received by a socialist candidate in an election in the United States, although not the highest proportion (that was the 1912 election, in which the Socialist Party secured 6% of the vote). Nevertheless, scholars tend to view the election of 1920 as being emblematic of the decline of the Socialist Party[16]Michael J. Klapper, The Response of Organized Labor to the Socialist Party Campaign of 1920, 10 INDUS. & LAB. REL. F. 53 (1974). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. as an electoral force in American politics. The Party and affiliated labor groups had already been weakened by years of government repression,[17]Investigation activities of Justice Department, Investigation Activities of the Department of Justice. Letter from the Attorney General Transmitting in Response to a Senate Resolution of October 17, 1919, a Report on the Activities of the Bureau of … Continue reading culminating in the Palmer Raids of 1919 and 1920, when thousands of people with alleged ties to leftist groups—a large portion of them immigrants—were arrested in a series of coordinated raids. The Party was further weakened in the years following the election by infighting, as splits developed between groups that chose to affiliate with the Soviet-dominated Communist International[18]“Documents” for American Consumption, 5 SOVIET UNION REV. 141 (1927). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and those that did not.

Aftermath and Legacy of the Espionage Act

The amendment to the Espionage Act, known as the Sedition Act, was repealed one month after the election. Despite the repeal, Debs remained in prison for another year, until his sentence was commuted by President Warren G. Harding, and he was released on Christmas Day, 1921.

Eugene Debs never recovered from his stay in prison, and died in 1926, six years after his release. He continues to be revered by organized labor and the American left. There is a social hall bearing his name in HeinOnline’s hometown of Buffalo, New York.

As of 2023, the Espionage Act remains law in the United States. In a curious twist of history, current presidential candidate (and former president) Donald Trump has also found himself afoul of the act, as he is currently under investigation for potential violations pertaining to his treatment of classified materials during and after his presidency.

Want to learn more about the history of labor, World War I, and the Espionage Act? Check out these blog posts:

- Crime of the Century: The Bombing of the Los Angeles Times Building

- Secrets of the Serial Set: The Red Scares

- Mayhem at Mar-a-Lago

- The November 11 Armistice: Marking an End to the Great War

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | To punish acts of interference with the foreign relations, the neutrality, and the foreign commerce of the United States, to punish espionage, and better to enforce the criminal laws of the United States, and for other purposes., Public Law 65-24 / Chapter 30, 65 Congress. 40 Stat. 217 (1917). This law can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | To amend section three, title one, of the Act entitled “An Act to punish acts of interference with the foreign relations, the neutrality, and the foreign commerce of the United States, to punish espionage, and better to enforce the criminal laws of the United States, and for other purposes,” approved June fifteenth, nineteen hundred and seventeen, and for other purposes., Public Law 65-150 / Chapter 75, 65 Congress. 40 Stat. 553 (1918). This law can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑3 | D. W. Brogan. Government of the People: A Study in the American Political System (1933). This book is available in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics collection. |

| ↑4 | G. Alex Sinha, Lies, Gaslighting and Propaganda, 68 BUFF. L. REV. 1037 (2020). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑5 | Amanda Alexander, The Genesis of the Civilian, 20 LJIL 359 (2007). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑6 | J. Michael Sproule, Clyde Miller: Twentieth Century Pioneer of Free Speech, 24 FREE SPEECH Y.B. 27 (1985). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑7 | Michael W. Casey & Michael A. Jordan, Free Speech in Time of War: Government Surveillance of the Churches of Christ in World War I, 34 FREE SPEECH Y.B. 102 (1996). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑8 | Report on the Chicago Strike of June-July, 1894, by the United States Strike Commission with Appendices Containing Testimony, Proceedings, and Recommendations (1895). This report is available in HeinOnline’s Labor & Employment: The American Worker. |

| ↑9 | In re Debs, Petitioner, 158 U.S. 564, 600 (1895). This case is available in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑10 | Stein, Emanuel et al. Labor Problems in America (1940). This book is available in HeinOnline’s Labor & Employment: The American Worker. |

| ↑11 | H. H. Kohlsaat. From McKinley to Harding: Personal Recollections of Our Presidents (1923). This book is available in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑12, ↑14, ↑15 | Eugene V. Debs. Writings and Speeches of Eugene V. Debs (1948). This book is available in HeinOnline’s Labor & Employment: The American Worker. |

| ↑13 | Debs v. United States, 249 U.S. 211, 216 (1919). This case is available in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑16 | Michael J. Klapper, The Response of Organized Labor to the Socialist Party Campaign of 1920, 10 INDUS. & LAB. REL. F. 53 (1974). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑17 | Investigation activities of Justice Department, Investigation Activities of the Department of Justice. Letter from the Attorney General Transmitting in Response to a Senate Resolution of October 17, 1919, a Report on the Activities of the Bureau of Investigation of the Department of Justice [i] (1919). This document is available in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set collection. |

| ↑18 | “Documents” for American Consumption, 5 SOVIET UNION REV. 141 (1927). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |