I unironically love the movie It’s a Wonderful Life. Yes, it is sweet and charming and sentimental. But it is also a dark, complex film about the slow, agonizing death of our childhood dreams, about staying put and feeling stuck, about rageful impotence against the cruel machinations of an unfair world, and how money really does matter more than some Beatles songs would have us otherwise believe. Pretty heavy stuff for a Christmas movie!

If you have never seen Frank Capra’s 1946 classic starring James Stewart and Donna Reed, move it to the top of your holiday watchlist. When you do, which version will you watch? It’s a Wonderful Life was originally filmed in black and white. But colorized versions of the film also exist; you can actually choose whether to stream the original black and white or a colorized version on Amazon Prime Video.

Colorizing black and white movies was all the rage in the 1980s. It was also a controversial technology that made its way from the Hollywood archives to the United States Senate. Using HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library and award-winning Business and Legal Aspects of Sports and Entertainment, let’s explore this curious chapter of Hollywood history.

Black and White and Color All Over

By the mid-1980s, computer technology had advanced enough that black and white movies and television shows could be colorized. Advocates of the technology argued that colorizing old black and white media made them more appealing to modern audiences. This renewed interest would, in turn, lead to revived revenue streams, in the form of television syndication and VHS sales of the colorized versions.[1]Elise K. Bader, A Film of a Different Color: Copyright and the Colorization of Black and White Films, 36 Copyright L. Symp. 133 (1986). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. The colorized version of It’s a Wonderful Life grossed over $2 million[2]Lon L. Fuller, Moral Right Protections in the Colorization of Black and White Motion Pictures: A Black and White Issue, 16 Hofstra L. Rev. 503 (1998). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. in its first year of distribution. The 1985 television broadcast of a colorized Miracle on 34th Street had higher ratings[3]Suzanne Ilene Schiller, Black and White and Brilliant: Protecting Black-and-White Films from Color-Recoding, 9 Comm/Ent L.J. 523 (1986). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. than previous black and white showings. And the 1988 colorized version of Casablanca was debuted on national television.[4]Dan Renberg, The Money of Color: Film Colorization and the 100th Congress, 11 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L. J. 391 (1988). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. In his testimony before the Senate in 1988, Roger L. Mayer, president and COO of Turner Entertainment Co., the company that led the colorizing revolution, testified that “5 to 10 times as many people saw each of the color-converted pictures in the last 6 months as had seen them in the prior 20 years on TV in black and white.”

Color Systems Technology, Inc. and Colorization, Inc. were the two main companies[5]Suzanne Ilene Schiller, Black and White and Brilliant: Protecting Black-and-White Films from Color-Recoding, 9 Comm/Ent L.J. 523 (1986). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. colorizing black and white films. Both used a similar process. It involved digitally scanning the film and breaking down the first frame of each scene into pixels. The colorizing software then interpreted the grey values to determine the original colors that were filmed.[6]Elise K. Bader, A Film of a Different Color: Copyright and the Colorization of Black and White Films, 36 Copyright L. Symp. 133 (1986). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Once those color values were assigned, the software continued assigning that color to the pixel until the scene changed.

Pretty nifty, right? The inherent flaw in this process, however, is that costumes, sets, and make-up on black and white movies were chosen because of what would render best in black and white film—and not because they were accurate representations of what the filmmakers would use if the movie were filmed in color. A famous example is the 1960 film Psycho. For the famous shower scene murder of Janet Leigh’s character, director Alfred Hitchcock used chocolate syrup for the blood, rather than stage blood, because it photographed better in black and white. If Psycho were colorized, the computer program would interpret the blood as chocolate brown, rather than red.

Because of these limitations, colorists did extensive research[7]Elise K. Bader, A Film of a Different Color: Copyright and the Colorization of Black and White Films, 36 Copyright L. Symp. 133 (1986). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. to ensure color palettes were correctly chosen. They evaluated the movie’s dialogue for in-universe references, did historical research, and consulted with people involved in the movie’s original production. When all else failed, however, colorists used their own artistic license to produce a final product that would be visually appealing to audiences. The process was not cheap. It cost approximately $350,000[8]Lon L. Fuller, Moral Right Protections in the Colorization of Black and White Motion Pictures: A Black and White Issue, 16 Hofstra L. Rev. 503 (1998). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. to colorize a full-length black and white feature film.

Derivative Works and Moral Rights

In 1987, the Copyright Office ruled that certain colorized films could be copyright registered as derivative works. A derivative work is defined as “a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgement, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted.”[9]17 U.S.C. 101. Found in HeinOnline’s United States Code. The Copyright Office’s decision gave copyright protection to the colorized version without affecting the copyright duration of the original black and white film.[10]Dan Renberg, The Money of Color: Film Colorization and the 100th Congress, 11 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L. J. 391 (1988). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

It is important to note that in 1986, Ted Turner,[11]Suzanne Ilene Schiller, Black and White and Brilliant: Protecting Black-and-White Films from Color-Recoding, 9 Comm/Ent L.J. 523 (1986). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. founder of Turner Entertainment Co., owned the libraries of MGM, RKO Pictures, and Warner Brothers—over 3,000 titles.[12]Technological Alterations to Motion Pictures: Implications for Creators, Copyright Owners, and Consumers: A Report of the Register of Copyrights (1989). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Business and Legal Aspects of Sports and … Continue reading This vault is the programming foundation for the cable TV channel Turner Classic Movies (TCM). Turner was also Color System Technologies’ main customer. A major concern was that, with colorized versions enjoying monetary popularity, “the copyright proprietors of these new versions may choose to keep the original films out of circulation and thus out of competition.”[13]Elise K. Bader, A Film of a Different Color: Copyright and the Colorization of Black and White Films, 36 Copyright L. Symp. 133 (1986). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. The movies, as the directors intended them to be seen, might remain locked in the vaults.

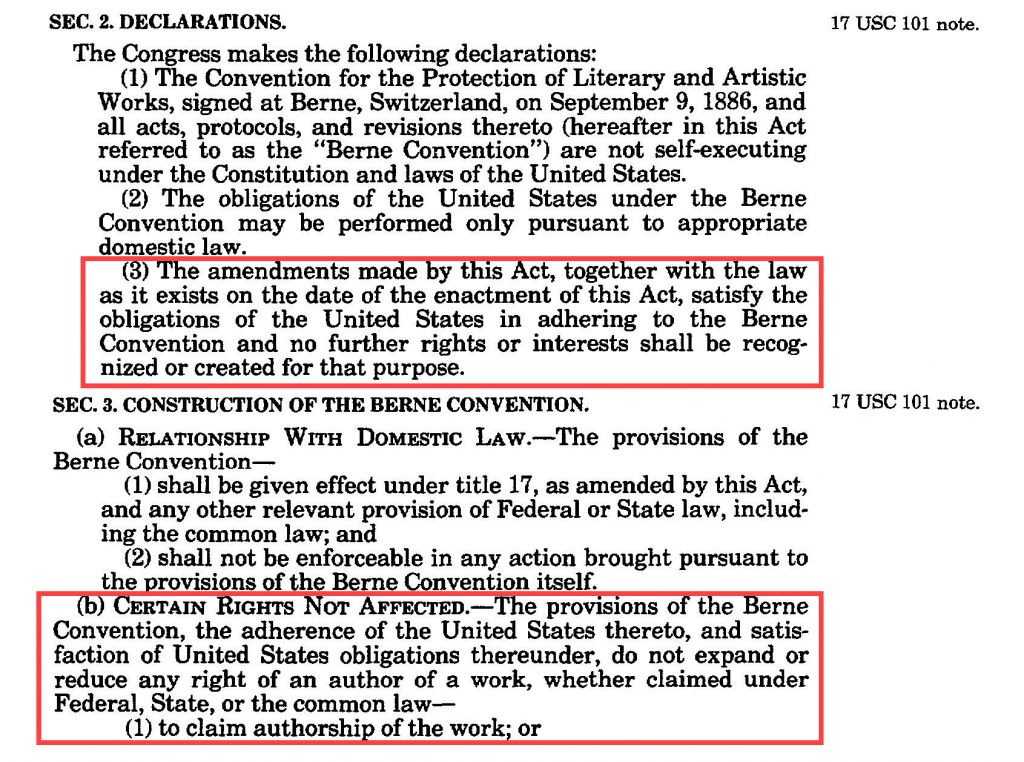

The copyright decision, however, said nothing about the morality of colorizing black and white movies. Moral rights take into consideration the personal relationship of the author to her work, separate from economic rights.[14]Technological Alterations to Motion Pictures: Implications for Creators, Copyright Owners, and Consumers: A Report of the Register of Copyrights (1989). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Business and Legal Aspects of Sports and … Continue reading The two most important moral rights are “the right of attribution”[15]Technological Alterations to Motion Pictures: Implications for Creators, Copyright Owners, and Consumers: A Report of the Register of Copyrights (1989). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Business and Legal Aspects of Sports and … Continue reading—the right of the author to be identified as such—and “the right of integrity”[16]Technological Alterations to Motion Pictures: Implications for Creators, Copyright Owners, and Consumers: A Report of the Register of Copyrights (1989). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Business and Legal Aspects of Sports and … Continue reading—the author’s interest in preventing unauthorized alterations that damage her reputation. Moral rights have long been a thorny subject in U.S. copyright law. Their inclusion in the Berne Convention was one reason why the U.S. refused to join. When the United States finally did join the Berne Convention on March 1, 1989,[17]102 Stat. 2853. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. it was with these legislative caveats:

Hollywood Goes to Washington

On May 12, 1987, the U.S. Senate held a hearing on colorization’s legal issues.[18]Legal issues that arise when color is added to films originally produced, sold, and distributed in black and white : hearing before the Subcommittee on Technology and the Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundredth … Continue reading Testifying before the Senate subcommittee were Hollywood legends Sydney Pollack,[19]Legal issues that arise when color is added to films originally produced, sold, and distributed in black and white : hearing before the Subcommittee on Technology and the Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundredth … Continue reading Woody Allen,[20]Legal issues that arise when color is added to films originally produced, sold, and distributed in black and white : hearing before the Subcommittee on Technology and the Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundredth … Continue reading and Ginger Rogers,[21]Legal issues that arise when color is added to films originally produced, sold, and distributed in black and white : hearing before the Subcommittee on Technology and the Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundredth … Continue reading as well as senior representatives from Color Systems Technology, Inc., Turner Entertainment Co., and Hal Roach Studios, which owned a principal interest in Colorization, Inc.

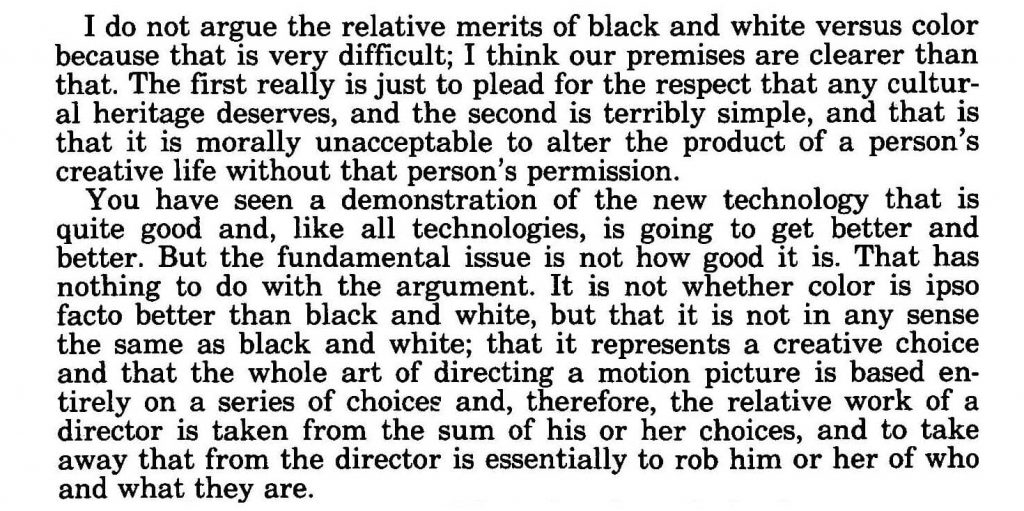

Arguing against colorization, Sydney Pollock summed up the issue as:

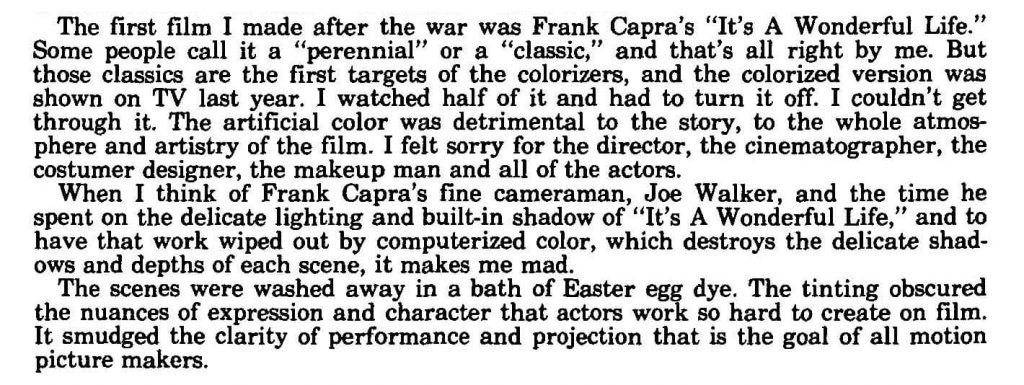

Ginger Rogers described to the Senate panel watching a colorized version of her film 42nd Street and feeling “outraged.”[22]Legal issues that arise when color is added to films originally produced, sold, and distributed in black and white : hearing before the Subcommittee on Technology and the Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundredth … Continue reading “I’m glad that Busby Berkeley [the film’s choreographer] isn’t here to see what they are doing to his art,” she said. “It would break his heart to see those brilliant dance numbers done-in by flat, lifeless computer color.”[23]Legal issues that arise when color is added to films originally produced, sold, and distributed in black and white : hearing before the Subcommittee on Technology and the Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundredth … Continue reading She also read into the record a letter from James Stewart, discussing the colorization issue both generally and specifically in regards to It’s a Wonderful Life.

National Film Preservation Act

Following this star-studded hearing, Congress attempted to regulate the colorization issue in aborted bills throughout 1987 and 1988. Pressure from industry guilds,[24]Dan Renberg, The Money of Color: Film Colorization and the 100th Congress, 11 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L. J. 391 (1988). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. such as the Directors Guild of America, intensified after the United States implemented the Berne Convention without adopting moral rights protections. Congress eventually settled on the idea of creating a National Film Commission that would create a National Film Registry of the nation’s most significant films, and preventing colorized versions of black and white films from being distributed under the film’s original name.[25]Dan Renberg, The Money of Color: Film Colorization and the 100th Congress, 11 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L. J. 391 (1988). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Frank Capra wrote an open letter to Congress, asking that classic films be protected from “the irresponsible assaults of greedy marketeers.”[26]Dan Renberg, The Money of Color: Film Colorization and the 100th Congress, 11 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L. J. 391 (1988). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. The Reagan Administration opposed the proposed legislation’s labeling requirements[27]Dan Renberg, The Money of Color: Film Colorization and the 100th Congress, 11 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L. J. 391 (1988). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. for colorized films, perhaps a surprising stance for a former actor.

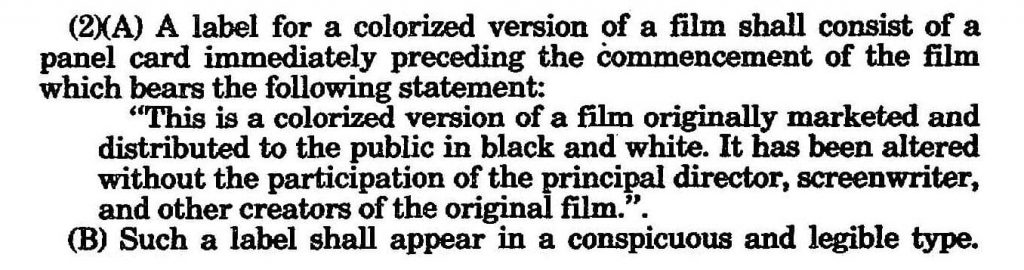

After much back-and-forth, on September 27, 1988, the National Film Preservation Act[28]102 Stat. 1782. This law is found in found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. became law. The Act created the National Film Preservation Board and it, together with the Librarian of Congress, curate the National Film Registry of “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”[29]102 Stat. 1782. This law is found in found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large films. Each year, twenty-five films are selected to be preserved in the National Film Board Collection at the Library of Congress. Outside experts and the public can recommend films for inclusion, and once a film is added, any version of the film that is “materially altered”[30]102 Stat. 1782. This law is found in found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large (such as colorized), needs to be labeled as such. The labeling requirements vary depending on the kind of alteration done, but for colorization, the rule is:

It’s a Wonderful Life was added to the National Film Registry in 1990.[31]55 Fed. Reg. 52845 (1990). The complete archive of the Federal Register can be found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Library.

Colorization ultimately proved to be an expensive fad that, for monetary reasons, Turner Entertainment stopped pursuing. However, advances once again in computer technology have made colorization faster and cheaper, and black and white movies are still converted to color. It’s a Wonderful Life was again colorized in 2007.

Digital alterations to movies and both their legal and moral merits have taken on a new urgency in the streaming age, when many consumers have purged their physical media for the convenience of digital copies. In doing so, they may be unintentionally watching a version different from the one shown in theaters, one that has been altered to conform to today’s morals, or polishes up now outdated special effects. Perhaps the most famous (or infamous, depending on your viewpoint) example is George Lucas’ persistent alterations to the original Star Wars trilogy (did Han Solo shoot first?). But that is a post for another day. Be sure you are subscribed so you don’t miss the debate.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1, ↑6, ↑7, ↑13 | Elise K. Bader, A Film of a Different Color: Copyright and the Colorization of Black and White Films, 36 Copyright L. Symp. 133 (1986). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑8 | Lon L. Fuller, Moral Right Protections in the Colorization of Black and White Motion Pictures: A Black and White Issue, 16 Hofstra L. Rev. 503 (1998). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑3, ↑5, ↑11 | Suzanne Ilene Schiller, Black and White and Brilliant: Protecting Black-and-White Films from Color-Recoding, 9 Comm/Ent L.J. 523 (1986). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑4, ↑10 | Dan Renberg, The Money of Color: Film Colorization and the 100th Congress, 11 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L. J. 391 (1988). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑9 | 17 U.S.C. 101. Found in HeinOnline’s United States Code. |

| ↑12, ↑14, ↑15, ↑16 | Technological Alterations to Motion Pictures: Implications for Creators, Copyright Owners, and Consumers: A Report of the Register of Copyrights (1989). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Business and Legal Aspects of Sports and Entertainment. |

| ↑17 | 102 Stat. 2853. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑18, ↑19, ↑20, ↑21, ↑22, ↑23 | Legal issues that arise when color is added to films originally produced, sold, and distributed in black and white : hearing before the Subcommittee on Technology and the Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundredth Congress, first session .. May 12, 1987. (1988) This hearing is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. |

| ↑24, ↑25, ↑26, ↑27 | Dan Renberg, The Money of Color: Film Colorization and the 100th Congress, 11 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L. J. 391 (1988). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑28 | 102 Stat. 1782. This law is found in found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑29, ↑30 | 102 Stat. 1782. This law is found in found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large |

| ↑31 | 55 Fed. Reg. 52845 (1990). The complete archive of the Federal Register can be found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Library. |